At its premiere, it was regarded as the new benchmark in the eleven-metre class. The high rig and generous sail area promised a lot of sailing fun for a touring boat. Below deck, she offered unprecedented volume, generous berth dimensions and a wet room with separate shower - another first for a 37-footer.

Success was not long in coming. The new machine designed by Judel/Vrolijk & Co. Hanse 370 got off to a flying start in sales. The first annual production run was sold out straight away in the summer of 2005. Within six years, a total of almost 700 units had rolled off the Greifswald shipyard's production line. Never before and never since has Hanseyachts achieved a comparable bestseller in such a short time.

And yet, from today's perspective, the boat doesn't look all that extraordinary - on the contrary. What was considered state of the art 20 years ago is now average at best - the evolution in large-scale boatbuilding has been so decisive.

Hull shapes of modern yachts outperform predecessor models

To make the development tangible for YACHT, Andreas Unger, the product manager responsible for the shipyard's sailing boats, virtually placed the hull of the Hanse 370 in that of the current 360. Apart from the sternpost and small segments of the lowered stern bulkhead, it disappears completely into the one-foot smaller sister ship of today. The Hanse 360 is higher in freeboard and significantly wider fore and aft, offering significantly more space below deck in a shorter length. In other words, while the Hanse 370 was the heroine of the 37-foot class in its day, the 360 now offers more comfort and space than a 40-foot yacht did back then.

And this is by no means the only trend that has continued unabated to this day. Because comfort requirements are generally increasing and the additional enclosed space must be nicely panelled and furnished, not only have the dimensions grown - the displacement has also increased, although ever lighter keels are being bolted under the hulls. This is possible because the wider constructions have more dimensional stability; otherwise modern yachts would weigh even more.

Deep Dive: Trend indicators

The hulls are getting longer and longer in the waterline and fuller and wider in the bulkhead, which is why the ballast ratio is continuously decreasing - while displacement is increasing at the same time.

Bigger, faster, better

There is much to suggest that the limits of growth have gradually been reached. Even leaving aesthetic aspects to one side, it is becoming increasingly difficult to imagine things going on like this forever. There are several reasons for this.

On the one hand, more volume costs more money - both to buy and to maintain. On the other hand, new constructions come up against restrictions, some of which are due to the area and are difficult to avoid. With a width of four metres, it becomes more difficult for owners of a Bavaria C38 or the Hanse 360, it can be tricky to find a suitable berth in the Baltic Sea.

So is it time for designers and boat builders to change course? Or will the trend towards residential boats continue, possibly with even greater consistency than before?

For Johan Siefer, Naval Architect and Managing Director of the leading German yacht design office based in Bremerhaven, the answer is clear in principle: "We always want more," says the head of Judel/Vrolijk. "And we simply expect to get more." This growth principle is reflected in all areas and is by no means limited to the yacht market. "You only have to compare the current VW Golf 8 with the Golf 1 from 1974. That's actually a completely different category of car."

In fact, despite limited resources, "bigger, faster, better" has been the maxim almost everywhere to date: ever more powerful smartphones, ever more gigantic televisions, ever more living space per household form the framework within which the trend in cruising boats also seems only inevitable.

Hull shapes of cruising yachts follow the racing sport

In order to be able to surmise how things might continue, the question is not so much why we came here in the first place, but rather on what path - and who drove the development.

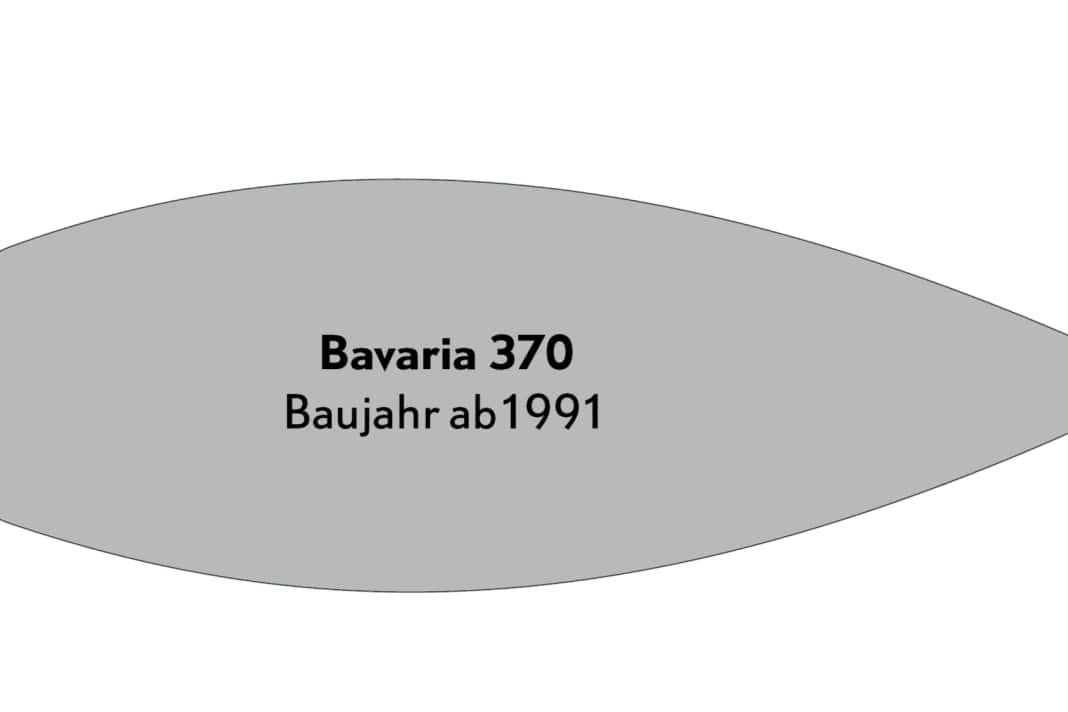

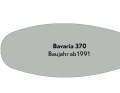

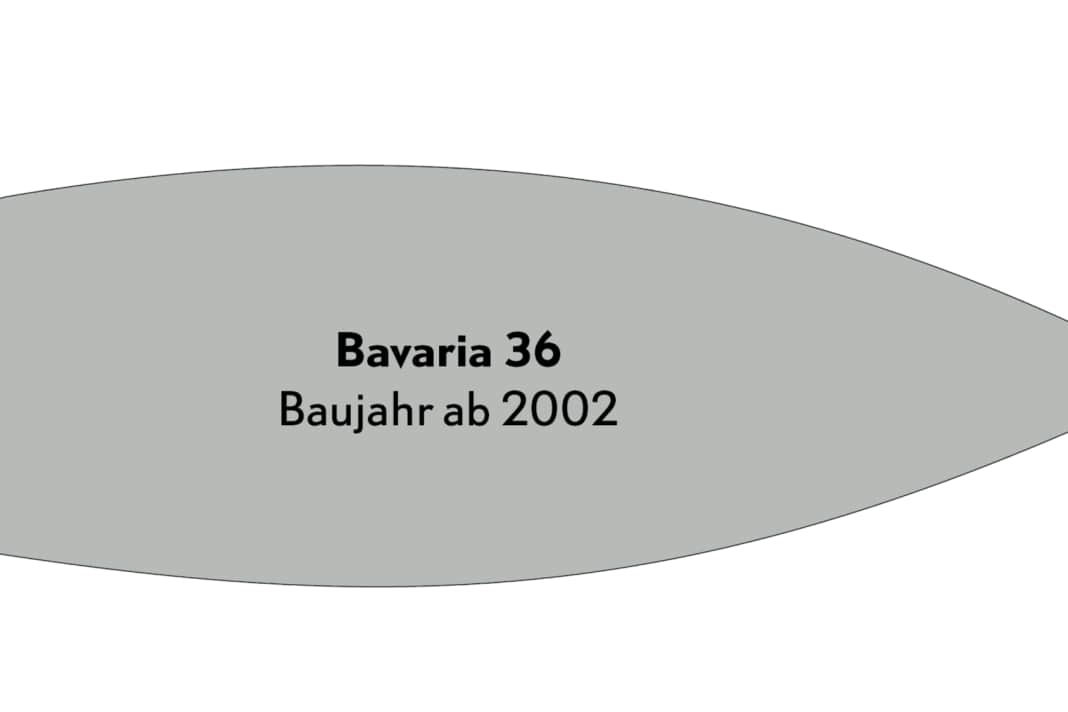

In principle, the yacht market is not really keen to experiment. Rather, it progresses via small-step evolutionary stages. Major leaps therefore only become apparent if you look at long time series, such as Bavaria's eleven-metre yachts from the past 35 years. In contrast, the changes from one model generation to the next are rather subtle.

The cruising yacht segment followed developments in regatta sport for decades, albeit with delays and never with the same consistency. Bulbous hull shapes with relatively long overhangs and short waterlines characterised the range from the 1970s to the 1990s, based on the International Offshore Rule.

With the transition to the IMS system and on to IRC and ORC, the sterns became straighter, the hulls wider, especially aft, and the appendages more efficient. Later, the large-scale production yachts even adopted design features such as chines and the increasingly fuller foredeck sections, which had their origins in Class 40, Volvo 70 and Imoca 60 ocean racing - so-called box rules, which leave plenty of room for development within certain parameters.

From pointed to blunt: changing hull shapes

The time series of deck views using the example of Bavaria's eleven-metre yachts demonstrates the direction of development in hull shapes.

Tapered ends: Bavaria 370

Wider jaws: Bavaria 36

Steeper stems: Bavaria Cruiser 37

Bulky hangers: Bavaria C38

Some trends in the touring sector are dispensable

Consequently, the trends in the regatta sector have always had a typifying effect. This applies to the visual habits and image of new designs as well as some fundamental design characteristics. It also seems only logical because the leading design offices acquired their merits in sport and later transferred this reputation and their latest hydrodynamic and aerodynamic findings to series yacht construction.

This is one of the reasons why the sailing characteristics of modern tourers today are still acceptable, if not better than those of their predecessors, despite their XXL format. When adapting racing attributes, shipyards have sometimes even adopted characteristics that originally served completely different purposes but could also be used for touring sailing: The wide stern sections with hard chines, for example, which were actually designed for more control and stability on fast room sheet courses, would have been absolutely unnecessary on displacement yachts. Nevertheless, they found their way into mass production because they created more berth width in the aft compartments - and visually conveyed progressiveness.

The spray rails in the foredeck of many Imoca racers, which are designed to prevent too much water from overflowing, also made it into the cruiser compartment in a roundabout way. The Hanse 360 has them, significantly modified, as does the Oceanis 51.1, with which Beneteau first introduced the principle of the tulip-shaped skim eight years ago. Designer Olivier Racoupeau did not create it to increase performance, but because it allowed more interior space to be realised at the height of the owner's berth.

It is important to be aware of this context: the inseparable intertwining of regatta and touring yacht development, at least until now, and the primacy of the formula mould even outside its actual area of application. Because if you think about it further, it opens up interesting perspectives.

Current trend: Scow

One of these has not yet arrived in the mainstream. The hull shape was established 125 years ago and has been making its way into ocean racing for 15 years: the scow. The flat-bow genre first emerged as a dinghy-like inland racer in the USA, where it is still actively sailed today. It owes its renaissance to the Mini 6.50 by David Raison, which was downright shocking at the time and shocked the yachting world with the "Teamwork Evolution" in 2010. "Unsailable in the wind" was the verdict of experts at the time. A highly innovative shipyard boss himself said: "Let's hope she's not successful, otherwise all yachts will soon look like this."

Well, the first part of his assessment was not to materialise, the second is yet to come. In the meantime, the hull shape, which is still controversial in terms of its appearance and design, has become the de facto standard in the Minitransat class, from where it first revolutionised the Class 40 and has now also changed the Imoca 60. This is because it offers great advantages in terms of buoyancy and stability on half-wind and downwind courses.

Only in GRP series production do scows still hardly play a role. It was only two years ago that the French company IDB Marine introduced the principle of a completely round, extremely voluminous foredeck section with the Mojito 6.50 in a sporty cruising boat. This summer, the French company is launching the next larger model: the Mojito 32.

Two more new products will follow in the course of the season that will cause a stir: The first of the Lift 45s, built in England, is due to take to the water in April. It is a construction by Lombard Yacht Design, based on their latest Class 40, and the developers used the extra metre in length to stretch the otherwise clog-like bow and make room for a reduced but complete extension for cruising. The Lift 45 is similar to the J/V 43which debuted two years ago as a small series (YACHT 05/2024).

Hull moulds of the future in the flat bow segment

Even more extreme is what Benoit Marie and former Beneteau designer Clément Bercault have come up with. The two want to launch the Skaw A a carbon fibre flounder almost five metres wide and twelve metres long, which should also offer superlative sailing performance thanks to its foils. At 20 knots of true wind, computer simulations predict a good 20 knots of speed for half-wind courses - with top speeds of over 25 knots.

And this should be possible without making any major concessions to comfort. On the contrary, the skaw has a light, spacious and pleasantly cool appearance below deck. The barely tapered bow section remains completely open and is converted into a semi-circular saloon; the navigation and galley are located amidships, with a wet room and two separate double berths behind.

This can be dismissed as a niche project, especially with a base price of 1.2 million euros, which is due to the complex carbon construction and small series production. However, the Skaw A has the potential to push the boundaries of what is conceivable and feasible - something that is denied to the majority of conventional cruising boats because they have to stay much closer to the mainstream.

Could their future look like this, at least to some extent? Wouldn't this hull shape allow for further growth in the interior without completely overburdening the infrastructure in the marinas with even wider main frames?

Civilian answers from the cruising boat sector

Sam Manuard, one of the most resourceful minds among world-class designers, believes it is possible. "I can also imagine the scow concept refined for cruising yachts," he says - "without making too many compromises in the wind." Manuard is aware of both the strengths and the biggest weakness of flat-bottomed boats: "The bow of the scows is so wide and flat that it generates hydrodynamic lift and helps the boat to break away from the wave. It is generally very efficient in any type of swell, as long as it comes from more than 60 degrees to the course direction." However, this is also the main problem: at the cross, the bow hits the wave violently due to its volume and wide attack surface.

Manuard's latest series boats show how he intends to circumvent the type-related disadvantage in terms of design: the new First 30 by Beneteau, which also originates from his computer, is to a certain extent the civilian answer - a design with a large keel and full foreship bulkhead, but still moderate lines for good all-round characteristics.

In collaboration with IRC expert Bernard Nivelt, Manuard took a more consistent approach to scow with the Pogo RCwhose stem is bevelled at the bottom like the Imocas and which resembles the aforementioned J/V 43 in the frame and on deck, but maintains a long waterline. She is modelled on the highly successful 35-foot one-off "Lann Ael 3", which won the title at the IRC Two-handed European Championship two years ago.

Night-time disadvantages of a scow-like cruising boat

What distinguishes all these new developments from conventional cruising boats is the weight factor. The relevant measure for this is the ratio of displacement to waterline length ("displacement-length ratio"). Like the sail carrying capacity, it is dimensionless. In order to start planing, yachts need values between 80 and 140 and a sail load factor of around or over 5.0. Tourers are currently a long way from achieving this; even many performance cruisers rarely fulfil both requirements.

A cruising yacht with a scow-like foredeck would therefore only benefit from the increase in space - similar to the takeover of the Chines a good 15 years ago - and not from better sailing characteristics on more open courses. On the wind, however, the disadvantages outweigh the advantages. And even in the harbour or at anchor, the design would be questionable: The flattening of the hull, otherwise known from the stern, would also become a disruptive factor in the foredeck even with a slight wave.

Is the broad market nevertheless once again focussing on regatta sport, because it is hardly possible to accommodate volumes in any other way? Or will the development this time bypass the cruising segment? That remains to be seen in the next generation. In any case, the development is being studied. And the new products for the coming season could intensify the discussion about the sense and nonsense of scows once again - also because usage and therefore purchasing habits are changing.

Hanjo Runde, head of Hanseyachts, recently described his models as "fantastic holiday homes" and noted a trend "away from pure sailing boats", where performance is important. For him, the trend is clearly "towards more living comfort". Is this paving the way for even chunkier boats?

Space and more space: yacht as holiday flat

In fact, this question arises if you don't buy cruising yachts primarily for sailing - more property than mobile, more leisure centre than sailing boat. Leading managers at another large shipyard group are also thinking along these lines because they fear that owners will otherwise migrate to catamarans and motorboats.

For the first time, manufacturers can even draw on valid data. More than 40 shipyards and 400 charter fleet operators are already installing Sentinel Marine's monitoring systems in their yachts, including almost all leading brands. Together, more than 25,000 boats can already be monitored and analysed during operation, with several thousand more being added every year. The information is available to the owners and - anonymised - also to the respective brands. It is a treasure that could change yacht development in the medium term.

Sentinel boss Marko Pihlar and his team of data analysts have analysed the use of the past five years for YACHT, differentiating between owner and charter boats and regardless of brand, size, type or orientation, in order to rule out any bias. From this, hardly any significant changes can be derived for privately sailed yachts.

The number of active sailing days in the charter fleets has fallen recently - from around 125 to 113 days per year; presumably as a result of the sharp rise in prices, especially in the high season. Privately owned yachts, on the other hand, sail for a good three weeks per season. This is in line with survey figures from France, which have hardly moved for more than ten years.

The Sentinel team also analysed the average duration of use per sailing day. It is consistently around 20 nautical miles. The individual values vary greatly, which is due to the generally longer trips during summer holidays.

Outside of the harbour, however, the number of moorings often remains in single figures, as YACHT research suggests. If owners leave the harbour at all, it is increasingly often only for a short day trip to the next anchorage in order to tie up again at the main berth in the evening. This makes Hanse CEO Runde's thesis that cruising boats are increasingly being bought as "holiday homes", or at least as such, appear plausible.

Focus on comfort and living quality

Jérôme Dufour, head of Jeanneau's sailing boat division, takes a similar view. "At the moment, the interior is the primary driver in the market," he says. He attributes this to the cooling capacity. "20 years ago, at most motor yachts had a cool box in the cockpit, then cats, and today customers expect it from a 40-foot monohull."

Because the cockpit has to become longer and longer, the saloon and thus the centre of gravity shifts forwards, which means more buoyancy in the foredeck and therefore a fuller hull shape. Can he imagine a Sun Odyssey with a scow bow in the medium term? Dufour doesn't want to go that far. "For a Sun Fast with a sportier orientation, definitely," he says. But he doesn't think the time has come yet for a cruising boat.

"We don't yet have the technology to reverse the spiral of weight, structural requirements and loads." The most difficult part of the development is to exceed expectations in terms of sailing performance and at the same time build a boat that "offers more comfort than anything available on the second-hand market".

Anyone listening to him realises that this is exactly what he is working on. "We have to bring the passion and craziness of sailing back to life," says Jérôme Dufour. It is quite possible that the era of gradual change will come to an end in a year or two and something truly new will emerge again. But he is not yet ready to reveal exactly what that might look like.