Swans are something special in Finland. They are considered sacred and are minted on coins, chiselled in stone and printed on stamps. The large, white birds with their elegant necks and yellow beaks symbolise elegance, purity and immortality. The origin of this lies in Finnish mythology: according to legend, a swan guarded the passage to the underworld. The hero Lemminkäinen was supposed to kill it in order to marry the daughter of the goddess Louhi. But he died in the attempt and only the love of his mother brought him back to life. The swan, however, remained unharmed - hence its symbolic power.

The country's artists, poets and thinkers made this their own. And in 1966, a resourceful entrepreneur named Pekka Koskenkylä did too. In the north, in Pietarsaari, he founded a shipyard for special swans: Nautor's Swans.

Sparkman & Stephens has made Nautor great

The boats have cult status. Especially those designed between 1967 and 1979 by the New York design office Sparkman & Stephens (S&S). They made the shipyard great and, like the swan in the Finnish national epic, play a special role in the history of sailing. Take the "Sayula II", for example, the shipyard's first Swan 65. In 1973/74, the Mexican millionaire Ramón Carlin and an amateur crew won the first Whitbread Round the World Race in a complete surprise. It was the most prestigious race in the world at the time, later known as the Volvo Ocean Race. A sensation.

Another example is the "Casse-Tête II". The Swan 36 made history at Cowes Week in 1968. She won seven out of seven races. It was a perfect, unprecedented result. The next test came in 1979: the legendary Fastnet Race. A severe storm took the fleet by surprise. Of the 303 boats that started, only 85 reached the finish line, 15 sailors died and 24 boats sank. Several Swans took part, braving the extreme conditions.

It is these stories that cement the reputation of S&S Swans - as not only elegant, but also powerful and indestructible boats. Like the swan from the Finnish legend. No wonder that even after almost 60 years there is hardly a bad word to be said about the boats. The fascination is unbroken. But where does it come from, what is the secret of the Scandinavian classic?

Boats of outstanding build quality

The search for clues begins at the end of September in the Flensburg Fjord. For the past 15 years, enthusiasts of aged Swans have been meeting here for the Baltic Rendezvous. What once began as a chance meeting between two sister ships has long since become an annual reunion between friends. Instead of club blazers and cocktail dresses, there are barbecued sausages and homemade cakes. Experiences and problems are discussed. People go from one boat to the next, inspect new switch panels or meticulously cleaned bilges or report on their trip to the Gulf of Bothnia.

"Everyone shares the enthusiasm for these fantastic ships," says Michael Seiler. He is the initiator of the Baltic Rendezvous and the link between the small Swan community in the Baltic Sea. "At the same time, you have the same worries if something does happen," he says. In the beginning, only 38-foot Swans came. In the meantime, the circle has expanded. In addition to two 38-footers, a 40-footer and a Swan 47 are also taking part this year. Fewer than usual, but a new owner couple has come along. Their boat is still on land, so they travelled there by car. New participants are always welcome, says Seiler - but on one condition: Their Swans must have been designed by Sparkman & Stephens.

The golden era of S&S swans

But what makes the combination so special? "The boats are very seaworthy and virtually indestructible," says Seiler. One reason: the thicker-than-average laminate. It is a relic from the early days of GRP construction. "In the 1960s, there was hardly any experience with this building material. That's why the laminate was thicker than it would be today," he says.

"Boats of outstanding build quality," says Werner Schliecker. He is the owner of the Swan 40. "We always went for the top shelf. Cost was not a factor." The rendezvous is also a fixed date in Achim Greiner's sailing calendar. He comes to the Flensburg Fjord from Travemünde every year. Wind and weather don't stop him - not even seven Beaufort, as was the case this time. His "Limaremca", a Swan 47 from 1979, can handle it, says Greiner. He appreciates the excellent sailing characteristics and the robustness that the boats embody.

Classic S&S Swans - and the IOR formula

Michael Seiler agrees: "Every cruise is a pleasure. These are not ships for the harbour. They are ships for sailing." They are still considered fast today, even though their measurements date back to a bygone era. Bulbous hulls, long overhangs, slender sterns. They are the heirs of the IOR measurement formula. The principle behind it: When upright, the boats have a short waterline. If they lie on their side, this is lengthened by the bulge, which now dips into the water - as a result, the hull speed increases.

Added to this are a moderate displacement, a high ballast ratio and a generous sail plan. The deck layout is also functional: The many winches on deck are striking. The halyards are operated from the mast, as was customary in the past.

More on the topic:

The more modern models have now moved a long way away from these features of classic S&S Swans, both technically and visually. The IOR belly has disappeared, the sterns are wide, the stem is negative - the aesthetics are radical in comparison. The length of the boat has also grown continuously. The Swan 131 is currently in the lead, closely followed by of the new flagship, the Swan 128. The Sparkman & Stephens era ended at 76 feet. What has endured over the years is the pointed arrow on the bow - the classic ornamental gill. It has become an unmistakable trademark

At the Baltic Rendezvous, hardly a word is said about the new route. The participants concentrate on the tried and tested. If you ask Michael Seiler about this, he can also see positive things in it: The reorientation of the shipyard is bringing the classic S&S designs back into focus, as a kind of counter-design. "They were the core of the shipyard," says Seiler. "That's how it grew up." A look at the beginnings makes this clear.

Search for a suitable design

In the mid-1960s, northern Finland was difficult to reach and economically isolated. It was there, in Pietarsaari, that paper mill representative Pekka Koskenkylä founded a shipyard in September 1966. Shortly beforehand, he had built an eleven metre long wooden boat in his spare time, which an acquaintance bought from him. This success motivated him to found the shipyard - which was to bear the name Nautor's Swan.

"'Nautor' sounded nautical to me," writes Koskenkylä in "Sparkman & Stephens Swan. A Legend", the standard work on S&S Swans, edited by Matteo Salamon. The name Swan came to him by chance, he says. A stroke of luck. "The name conveys the values that characterise the company: Elegance, strength, beauty. These connotations were important for the success."

At this point, you will find external content that complements the article. You can display and hide it with a click.

Because he lacked drawings for his boats, he asked the local yacht club who the best designer in the world was. Sparkman & Stephens, he was told. A letter to the New York address went unanswered. Finally, he picked up the phone and got Rod Stephens himself on the line. He had an appointment in Finland soon anyway, so they arranged to meet.

Robust, resilient boats thanks to meticulousness

Sparkman & Stephens was already a world-renowned design office at this time. The brothers Olin and Roderick Stephens founded it in New York in 1929 together with Drake Sparkman and became famous with America's Cup designs such as the J-Class "Ranger" (1937).

Olin Stephens was the design genius, the creative mind at the drawing board. Sparkman, a far-sighted boat broker, had discovered him and encouraged the young talent. But Stephens was by no means just a theorist: he won prestigious regattas such as the 1931 Transatlantic Race and the America's Cup in 1937 and 1958.

His younger brother Rod, on the other hand, was regarded as the practical man. "He was a man of detail who never missed a thing," Olin Stephens once said in an interview. At the same time, he had the rare talent of being able to quickly find his way in all situations - as a sailor and as an engineer. Rod Stephens' knowledge was essential for the shipyard, writes Koskenkylä. He meticulously inspected every boat, noted defects on yellow slips of paper and only ticked them off once they had been rectified.

Lars Ström describes this meticulousness in the Swan standard work as follows: "The first thing Rod did during his inspections was to have himself pulled into the mast to check the rigging." This precision gave the Swans their reputation as robust, resilient boats. Ström knows the shipyard from the inside: From 1973 to 2005, he was involved in all phases of production as technical manager. Together with Matteo Salamon, he analysed the history and technical details of the S&S Swans - documented in the Swan standard work and on the S&S Association website.

It should be plastic

When Koskenkylä and Rod Stephens met, the chemistry must have been right straight away. Although Koskenkylä lacked both the expertise and the money, he received the drawings for a 36-foot sloop. It was to become the basis for the shipyard's first model, the Swan 36.

Why did Stephens give the ambitious Finn the drawings? Koskenkylä suspects that he struck a nerve with his suggestion to build the boats from plastic, which was new at the time. However, another point was decisive: Koskenkylä fulfilled a key requirement of the design office. Even before the first boat was launched, he had to have sold the first examples. And he succeeded.

The S&S Association

The association brings together owners of classic Swans drawn by Sparkman & Stephens. It gives members free access to an extensive archive. At the same time, it is a forum for purchasing, maintenance, regattas and much more. More information: classicswan.org

Back in Pietarsaari, he immediately looked for suitable halls and capable boat builders. There were plenty of them. Jakobstads Båtvarv has been building wooden boats in the region since the beginning of the 20th century. These include, for example, the Hai boat class, which is still popular in Finland today. However, the boat builders had no experience with plastic. So the young shipyard had to buy in expertise from outside. They also tried out a lot of things and experimented with the new type of glass fibre reinforced plastic (GRP). This was tedious, but had one advantage: it allowed them to break new ground and not be trapped in rigid production processes.

Another defining circumstance was the remote location in the north of Finland. This forced the shipyard to be largely self-sufficient. If a propeller or a deck part was missing, it meant inconvenient delivery routes. So they made them themselves, writes Koskenkylä. One day, when a mast supplier got into difficulties and threatened to delay the delivery of finished boats, the shipyard decided without further ado to build masts itself. It was a similar story with the propellers: several customers reported problems that the manufacturer was unable to solve. So the local blacksmith was commissioned to manufacture the propellers - until a customer offered to produce cheaper ones. He founded a company in Denmark that still exists today: Gori.

Rolls-Royce of the seas

Ake Lindqvist, a representative of the Lloyd's shipping register in Finland, helped with the handling of the plastic. He had already built his own 43-foot boat from plastic and, as a Lloyd's man, knew the material properties inside out. "This was very useful because Lindqvist emphasised quality and robustness. This earned the yachts a reputation as the Rolls-Royce of the seas," said Olin Stephens.

Nautor was not the only shipyard to use GRP at the end of the 1960s. Various other manufacturers mainly built motorboats or dinghies from the new material. However, the market from 40 feet upwards was sparsely populated. Comparably sized yachts were available in the USA from CAL or Columbia - but their quality was hardly convincing.

Much of the competition remained with timber construction, as many people found it difficult to come to terms with plastic. The prevailing opinion was that large boats had to be made of wood. This is also the reason why the first Swan 36 was intended to look like a varnished wooden boat, writes Koskenkylä. But this view changed over time. First slowly, then more and more quickly, plastic became the material of choice.

Rise to a global brand

This can be seen in the shipyard's growth figures. Four boats were built in the first year. The first Swan 36 was still made of mahogany and was intended as the master model for the negative mould. This was then used to build three more in plastic. After that, the numbers skyrocketed: between 1967 and 1970, 90 hulls left the halls. A new model was added in 1969: the Swan 43, followed a year later by the Swan 55, 40 and 37.

At the same time, in 1969, a fire destroyed the main building and an entire production line. The real problem, according to Koskenkylä, was not the destruction, but the insecure suppliers. They feared for their money. They wanted to be paid immediately for the goods they had supplied to the shipyard on credit.

Insolvency was imminent, but Koskenkylä found help from his old employer, Schauman, the owner of the paper mill. The company relieved him of the financial burden and invested in the young shipyard - in return, Koskenkylä had to cede shares to Schauman.

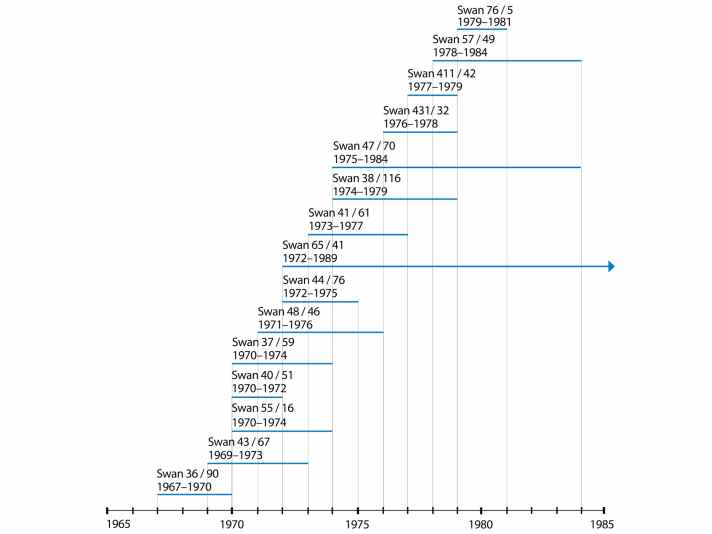

From then on, things went uphill for the shipyard. Around 100 boats left the halls every year. And the trend was rising. New models were constantly being added. Sparkman & Stephens alone designed 15 different models for Nautor. They were produced until 1989. The shipyard produced a total of 821 boats based on the US-American designs.

Shipyard sees itself as a technological pioneer in boatbuilding

However, the shipyard also began working with other designers much earlier. Between 1978 and 1981, New Zealander Ronald "Ron" Holland designed five boats. The first designs by Germán Frers followed at the beginning of the 1980s. To this day, the Argentinean's unmistakable designs have had a decisive influence on Swan development.

Shipyard founder Pekka Koskenkylä was no longer on board at the time. Although Schauman's involvement relieved the financial pressure, Koskenkylä recalls, the development of the shipyard took a different direction than he had hoped. In 1973, he finally left the company, which changed hands several times in the following years.

Today, almost 60 years after its foundation, Nautor's Swan has long since become a global brand. Although the modern Swans break with the traditions established by Sparkman & Stephens in many respects, one decisive commonality remains: The shipyard continues to see itself as a technological pioneer in boatbuilding.

Pekka Koskenkylä relied on the new type of plastic from the very beginning, first convincing the New York designers and then the entire sailing world. Nautor's Swan is continuing this pioneering role under new management - today with prepreg carbon fibre and tempered vacuum processes. The shipyard remains true to its principles and continues to emphasise both elegance and strength in its boats. And so the message of the Finnish legend still applies: You can rely on a swan.

Interview with Matteo Salamon, founder of the S&S Swan Association

Mr Salamon, you are both an art dealer and a Swan lover. How does that fit together?

Perhaps I was born with a penchant for beautiful things. When I saw a Swan for the first time at the age of 16, I was immediately fascinated by its beauty. I didn't know much about the technical side of things back then, but its shape and construction seemed perfect to me. I must add that when I talk about these boats, I always mean those designed by Sparkman & Stephens.

What's so special about it?

Before I bought my own Swan (first a 38, later a 47; editor's note)I had the opportunity to meet Olin Stephens in person. He made me realise what S&S was all about: they didn't just design the shape, they designed everything on board. Every detail was thought through to perfection, from the hull, deck and sail plan to the electrics. When they commissioned a project, they wanted it to be complete. This differs significantly from modern approaches, where many things are created by different designers.

How was this procedure guaranteed?

Part of the agreement was that each boat would be inspected by either Rod Stephens or someone he trusted before delivery. You can imagine what an effort that was! In the 1970s, the journey from New York to the north of Finland took around two days.

Such close co-operation between designers and shipyard would be unthinkable today.

What characterised this collaboration?

I think it was the trust that Rod Stephens, one of the most respected sailors of his time, had in the shipyard founder Pekka Koskenkylä - and vice versa.

Finland was a rather poor country in the middle of the 20th century and Pietarsaari was hardly on the yachting map. S&S, on the other hand, was in demand worldwide. How does that fit together?

Yes, that's right. This meant that the shipyard had to start from scratch for many things. If they needed a certain screw, they had to make it themselves.

Series production with GRP was also new territory.

That's right, at that time working with it was still a great adventure. The composition of the components was a completely undiscovered field. Initially, incorrect mixing ratios led to explosions. So they called in help from

experts from abroad. This enabled them to produce everything in-house. The best materials were used, which is reflected in the quality of the boats.

What role did shipyard founder Pekka Koskenkylä play?

Pekka wanted Finland to be known for more than just its paper. England had its Rolls-Royces, he wanted the same for Finland, only with boats. Rod Stephens believed in the crazy Finn. Even though he had no money, as he realised when they met in 1966. So one condition of the collaboration was that Pekka had to sell the first yachts in advance. He succeeded. In Italy we say:

He was able to sell glass to the Inuit.

Even today, the bond between Swan owners and the shipyard is still considered strong. Why?

I think that's because the shipyard has been building boats for six decades. Incidentally, the bond also applies to owners of classic and modern Swans. You notice this at the Swan meetings in the Mediterranean, for example.

Modern and classic Swans differ considerably, both technically and visually.

Yes, the S&S swans were designed to be safe in rough seas and in winds over 20 knots. Today the market is different. People don't want to cross oceans or sail in strong winds. They need space to sunbathe. No wonder you hardly see the modern boats in the Fastnet or Sydney Hobart Race. I think they have lost their poetry and perfection.