- Shipyard founded at the age of 21

- Although Uffa Fox's first skerry cruiser did not win, it turned out to be seaworthy

- Debts force Uffa Fox to write a book

- "Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Construction" was a complete success

- Returning to his beginnings as a designer

- The "Flying Fifteen" became the "Flying Family"

- His connection to Prince Philip made Uffa Fox famous

- More books, but also motorboats and aeroplanes

When a sailor moors his boat to a bell buoy in heavy swells, he is either deaf or in great distress. The sea scouts on board the 9.30 metre long and only 1.67 metre wide whaling boat "Valhalla" were not deaf when they moored at the Cap de la Hève buoy after midnight on a July day in 1921 and after passing through the last lock of Le Havre due to decreasing winds and strong tidal currents. The young people waited there in agony until the wind picked up from the north after a while. The sails could be set and the return journey across the channel began.

Paris instead of Solent

The strong wind carried them towards their destination until half past one in the morning, when it dropped so that they had to row from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon. The strong tidal currents around the Isle of Wight did not allow them to call at their home port of Cowes. The open boat was pulled onto the beach and a final night of bivouacking began. Two of the boys made their way to Cowes on foot. After a two-week trip, they had to return to their training centre the next morning. They walked barefoot, as the captain of the ten-man crew had forbidden them to take shoes and socks with them. To toughen up and save weight.

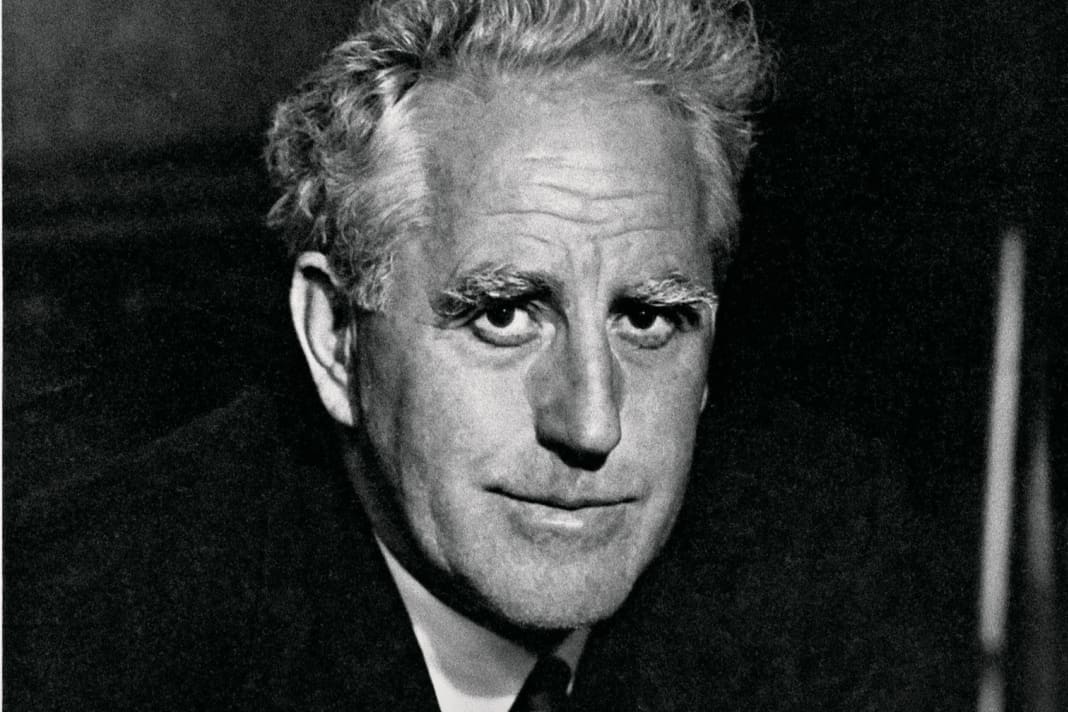

The 23-year-old captain was called Uffa Fox. The crew members were between 14 and 18 years old. Their parents thought they were travelling in the Solent. In fact, they had tried to secretly cross the English Channel and sail up the Seine to Paris. Due to time constraints, they had to give up shortly before reaching their destination. On their return, the parents were horrified and took the Cowes Sea Scouts board of directors to court. They had to resign as a result. Uffa Fox was no longer allowed to lead a youth group, which didn't bother him too much, as he was firmly convinced that he had given the youngsters an unforgettable adventure.

As a student, Uffa Fox was a know-it-all who didn't fit into the system

Uffa Fox was born in Cowes on 15 January 1898. He left school at the age of 14 and began an apprenticeship as a boat builder. His niece June Dixon describes him in "Uffa Fox: A Personal Biography" as a know-it-all pupil who got in his own way. Teachers and parents were convinced that he would have been intelligent enough to master all qualifications with ease, but even then he didn't really fit into the system.

But then Fox was lucky enough to learn in an innovative boatbuilding workshop during his seven-year apprenticeship at SE Saunders in Cowes. The First World War was breaking out, technical superiority was essential for survival, and experimentation was part of it. Sam Saunders had patented a new technique. He constructed hulls with four layers of mahogany veneer, held together crosswise with waterproof glue and copper wire. He used this to build watertight hulls, naval aircraft, nacelles for airships and the "Maple Leaf IV" racing boat.

After a long working day in the shipyard and at weekends, Fox was drawn to the Sea Scouts, where swimming, sailing, rowing, camping trips and sporting competitions offered him a wonderful change from the adult life of the working world.

The oak tree in the garden instead of money

A sailing enthusiast as he was, he convinced his father that he had to build his first six-metre dinghy cruiser after attending evening classes in boat construction for a few weeks. He refused financial support, but offered an oak tree in the garden as a source of material. Uffa Fox motivated friends to help him cut down the tree. But as soon as the components were sawn out, he lost interest.

A few months later, at the second attempt, Fox built a 16-foot sailing canoe in the garden shed with the help of his father, which he sailed along the coast.

The teaching company forgot to put him on the list of employees important to the war effort.

In his training company, Uffa Fox managed to annoy the older boatbuilders by being a know-it-all and giving unwanted advice. When war broke out, they somehow forgot to put him on the list of employees who were important for the production of war goods. He was promptly drafted into the navy.

Shipyard founded at the age of 21

After the war, Fox, newly married, founded his own shipyard at the age of just 21. Creative and unconventional, he set it up in a decommissioned ferry on the Medina River, which he had acquired with financial help from his father. The passenger compartments became his home. Engine rooms served as workshops or storage, and the central loading area was roofed over and could accommodate several dinghy hulls at the same time.

As a passionate regatta sailor and with his experience in lightweight construction from his apprenticeship, Fox began developing planing dinghies in 1927. Although he was not the "inventor" of the planing dinghy, as is often claimed, his designs and publications contributed greatly to the spread of the new planing hull shape.

The 14-foot dinghy was recognised as a British design class at this time. The class was a great field of experimentation for designers. With the construction of two prototypes, the young shipyard owner moved away from the still round hull cross-sections of the usual designs towards his radical design of the planing dinghy. The front section had a V-shape, which provided the initial lift to raise the hull. This allowed the rear, flat section to glide.

Overwhelming success for Uffa Fox's planing dinghy "Avenger"

Fox was able to utilise all of his previous experience in the design of his third dinghy "Avenger". The result was a boat that was able to plane in moderate winds, both on a room sheet course and upwind, while remaining controllable. The success was overwhelming. Fox finished 57 races of the season with 52 first, two second and three third places.

Weight is only useful for a steamroller"

True to his motto "Weight is only useful to a steamroller", Fox designed "Avenger" to be as light as was possible with the techniques of wooden boat building known to him at the time. Uffa Fox and two crew members proved that the open 14-foot dinghy was nevertheless seaworthy on a 100 nautical mile ride across the English Channel to Le Havre for regatta sailing. After a subsequent 37-hour journey home through heavy seas and steamboat traffic, they also took part in the regatta that had just started in their home waters.

For some time, the regattas of the 14-foot dinghies in England were jokingly referred to as "Fox-hunting", as the competitors only ever sailed after Fox's dinghy.

Although Uffa Fox's first skerry cruiser did not win, it turned out to be seaworthy

The first keelboat he built was "Vigilant", a design based on the archipelago cruiser rule. In the summer of 1930, Fox sailed the 22 square metre archipelago cruiser with two friends from Cowes to Sandhamn in the eastern Swedish archipelago to take part in the Royal Swedish Yacht Club Centenary Races. They arrived in the middle of the regatta action and, to the surprise of the dinghy sailor who was used to winning, had little success. They were nevertheless awarded a trophy - for travelling across the North Sea. Until then, skerry cruisers were not considered suitable for the high seas.

On the return journey from Cuxhaven to Lowestoft with only one other sailor, Fox had to sail his light, slim boat against a heavy storm, which he managed surprisingly well. According to the knowledge of the time, sailing boats for the high seas should be high-sided, heavy and robust. Fox recognised the seaworthiness of the lightweight hull, which did not force its way through the waves, but floated lightly and elegantly over them like a Viking boat.

Uffa Fox saw Olympic potential in the sailing canoe

The designer believed that the International Sailing Canoe was the ideal boat for the Olympic one-man class. The canoeist had to master the mainsheet and jib sheet as well as the centreboard and planing seat. There was no greater sporting challenge in sailing at the time.

In 1933, Uffa Fox visited America with his sailing friend Roger de Quincey to challenge the sailing canoe scene there. Fox designed two sailing canoes for this purpose, "Valiant" and "East Anglian", which differed significantly from the round canoe shape of the Americans with their V-shaped bow area and the relatively wide and flat underwater area in the rear third. They started in Quebec and won all the important regattas on their way to New York, including the trophy donated by the New York Canoe Club.

The American canoes sailed with outrigger boards and were ketch-rigged. Two masts were also required by the British challengers. Fox interpreted these regulations in his own way and placed another small mast in front of the unstayed mast at an angle so that it touched the main mast in the upper third and could carry the foresail.

In his opinion, the design of the winning model should always be passed on to the losing team in order to promote further development in sailing.

It was typical of Fox that he handed over the plans of his successful model to the losers. In his opinion, the design of the winning model should always be passed on to the losers in order to promote further development in sailing.

Debts force Uffa Fox to write a book

Even before the preparations for Fox's sailing canoe adventure in North America, the publisher Peter Davies had approached him with the proposal to write a special book about sailing. Although he had already enthusiastically published his findings in several magazine articles, Fox was not sure whether his discipline would be enough for a whole book and declined. He was also already more than busy as a designer, shipyard manager and regatta sailor. When Fox received an unannounced visit from his banker just two days before his departure for canoe sailing in America, who this time did not engage in the usual drinking session that always ended with compromises skilfully negotiated by Fox, he felt backed into a corner. The bank demanded the cancellation of the expensive venture, which would have added to his mountain of debt. In desperation, Uffa Fox telegraphed the publisher and negotiated an advance payment for his first book.

After his successful trip to America, Fox used his diaries, regatta experiences and notes from his most recent sailing canoe tour to help him work on the book. Unbiased and enthusiastic about the boat designs of others, he wrote to well-known designers with the request to publish their designs in his book. To everyone's astonishment, he soon had more plans of "competitors'" boats on his desk than he could include in one book.

"Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Construction" was a complete success

Fox's first book, "Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Construction", told of his adventures and designs, and contained his own thoughts on sailing and comments on the constructions of well-known designers. It was a resounding success and was reprinted several times in the years that followed. The steady flow of royalties delighted Fox, whose lifestyle always consumed more than he earned. He decided to invest more and more time in writing, lecturing and producing magazine articles.

The steady flow of royalties delighted Fox, whose lifestyle always consumed more than he earned.

His wife Alma, a teacher by profession, did the bookkeeping at Fox and mediated between the staff and the moody boss. Now she also took on the role of the driving editor of his books.

However, when she was introduced to a new woman at his side, in addition to a few tacitly accepted infidelities by her husband, she separated from him and Fox's new love Cherry moved in with her son Bobbie in the country house purchased not long before by Alma and Uffa Fox. Fox once again persuaded his father to invest his savings in a new company, Uffa Fox Limited, and in 1938 he bought the Medina shipyard, including the house, and set up his business and main residence there.

During the war, Uffa Fox benefited from government contracts

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Fox had lost most of his boatbuilders due to a dispute with his otherwise loyal employees and their union caused by his unruly outbursts of anger. However, due to the uncertain economic situation, he was now able to recruit new craftsmen without union membership with ease. Despite heavy air raids and the partial destruction of his shipyard, he now had enough money to invest in a country estate thanks to orders from the Ministry of War. He was able to afford gardeners, cooks and servants, organise parties and go horse riding or take pleasure trips in his cars despite limited petrol vouchers.

When the war finally came to an end after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a source of money that had been abundant for Uffa Fox until then also dried up.

Returning to his beginnings as a designer

In the post-war period, Fox once again focussed on the design and construction of pleasure craft. When the Royal Yachting Association asked several designers to create a twelve-foot sailing dinghy, Fox was able to draw on an existing design. He had already designed boats of this size for the Oxford and Cambridge University teams and submitted his 12-foot Cambridge design for the competition.

His design won the contract and the Fairey company began production of the "Firefly" single-handed boat, which was nominated for the 1948 Olympic Games in Torquay shortly afterwards. The gold medal went to the then 20-year-old Paul Elvstrøm. However, the class was replaced by the Finn dinghy at the very next games.

In the book "Das Boot für dich" (The boat for you) published by Günther Grell at Delius Klasing & Co in 1966, the cabin cruiser "Atalanta" was highly praised as a trailerable family boat. The innovative design by Uffa Fox for series production made of moulded plywood had a futuristic look with its whale deck and double centreboards. In fact, the aim of the design was not to create beautiful lines, but to optimise it from a manufacturing point of view and to gain space based on market analyses. Between 1956 and 1968, Fairey Marine produced 291 Atalantas in lengths of 26 and 31 feet.

The "Flying Fifteen" became the "Flying Family"

When he was almost 50 years old and Fox already had more than 20 years of experience with planing dinghy hulls, the designer wanted a boat with the characteristics of his dinghies, but without the risk of capsizing. He sketched out the lines of a planing keelboat 20 feet long with the rig of the international 14-foot dinghies. After regatta successes, energetic efforts to found a class association and skilfully placed publications, the Flying Fifteen became a success. Uffa Fox went from one regatta to the next with the hull and rig on the roof of the car and the 200-kilogram keel sticking out of the boot. More than 4,000 of the Flying Fifteen were built.

Fox was so enthusiastic about the success of his gliding hulls that he developed the "Flying Family" in the following years. One of his outstanding designs was the Flying 30 "Huff of Arklow". Built in 1951 by John Tyrrell & Son in Arklow, Ireland, it is considered to be the first ocean-going yacht with a split lateral plan and designed for planing.

Despite all his successes, Fox had to part with his expensive country home for financial reasons. With a loan from a friend, who was the chairman of his sailing club at the time, he bought an old warehouse right on the waterfront. Out of gratitude to his patron, he named it "The Commodore's House", which he extended over the following years and kept until the end of his life.

His connection to Prince Philip made Uffa Fox famous

In the summer of 1949, Fox met Prince Philip for the first time at a regatta in Cowes. The people of Cowes had given Elizabeth II and Prince Philip the Flying Fifteen "Coweslip" as a wedding present. After regattas, parties and drinking sessions with the Prince, Uffa Fox became famous throughout the country thanks to the British press.

His fame led to television shows, expert appearances at boat shows and recordings of shanties sung by him. Despite this prominence and his outstanding yacht designs, Fox was sadly denied the title of Member of the Institute of Naval Architects. He had never studied. All efforts to obtain the coveted title and add it to his designer title were rebuffed with the laconic suggestion that he should study.

But then an opportunity finally arose that Fox knew how to capitalise on immediately. Years earlier, he had designed his dream yacht "Stardust" for a circumnavigation. However, he was never able to build it for himself. But whenever the enquiry for the design of a long-distance yacht landed on his desk, Fox took the design back to the drawing board. In 1940, for example, the Yawl was reduced from 36 to 25 feet and built in teak in what was then Bombay. She was later sold to Lord Runciman, who wanted to replace her with a new build after many fine years.

Viscount Runciman turned to Uffa Fox for the new design. While working on the new ship, he realised that his client was none other than the president of the renowned Institute of Naval Architects. He openly approached the lord about his problem, and it only took three months for it to be solved to Uffa Fox's satisfaction - he could now proudly call himself a member of the elite institute.

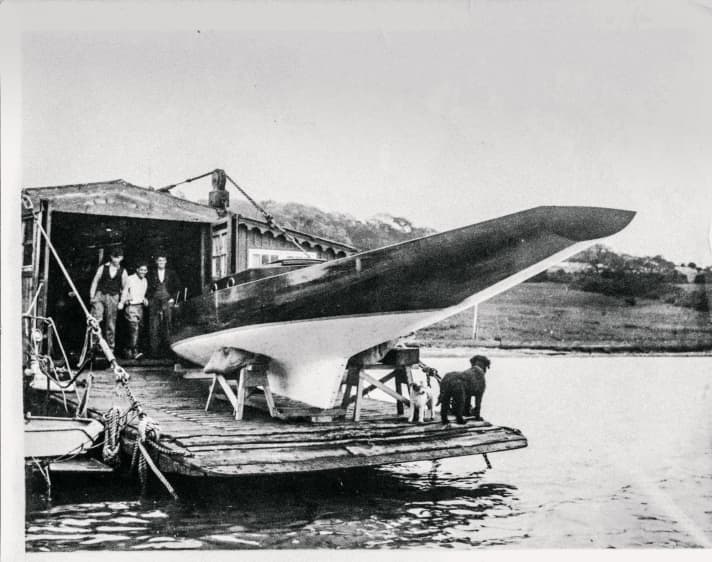

More books, but also motorboats and aeroplanes

After 20 years of abstinence, Fox finally devoted himself to writing books again. In the summer of 1959, the book "Sailing Boats" was published, followed a year later by "According to Uffa". Both books were successful. In addition to sailing boats, Fox's portfolio in the following years also included rowing gigs, paddle steamers, seaplanes and motorboats. In 1955, he was awarded the coveted title of "Royal Designer for Industry" for his work to date. For John Fairfax, the first solo rower to cross the Atlantic, Fox designed the rowing boat "Britannia" in 1968, a self-righting and self-draining construction made of mahogany wood.

Sailing and partying were more important to Uffa Fox than earning money

Throughout his life, it had been more important to Uffa Fox to design, sail and party than to earn money. Although he had successfully published his designs and ideas, he had not been able to market them sustainably enough for the income to easily finance his lifestyle.

The last boat he built for himself was "Ankle Deep", a 25ft open motorboat that hung over the water on davits from his "Commodore's House", ready to take him out on the water or to dinner on the royal yacht during Cowes Week.

Uffa Fox took part in his last regatta at the age of 70. During Cowes Week 1972, he was once again hoisted aboard "Coweslip", Prince Philip's Flying Fifteen. They had competed in countless regattas together on this boat. Fox was also taken aboard the royal yacht "Britannia" for dinner one last time. He died two months after the exertions of the regatta week on 27 October 1972.

Text: Detlef Teufel