- Resentment towards the English united all

- "Corsør" true to the original - except for two electric motors

- Young people build the "Corsør"

- Of course, the mini three-master can also sail

- Red thread in cordage for theft protection

- 600 grams of gunpowder per shot

- Technical data of the "Corsør

Korsør is located on the west coast of Zealand, but at the eastern end of the impressive Great Belt Bridge. A few of Denmark's largest warships are based at the traditional naval base here, when they are not on deployment or training voyages. On some days, a strange vessel can be seen passing by the grey steel hulks: a small wooden ship with three masts, eight oarsmen and a heavy cannon on the stern. Care must be taken when the "Corsør" suddenly stops to realign the stern with the overhanging cannon. At the latest when the commander stretches his mouthpiece into the sky to shout a warning, you need to protect your eardrums. The subsequent flash of fire is invisible to the naked eye, but the bang is deafening. After the sulphurous smoke has cleared, peace reigns once again in front of the small harbour town on the Great Belt.

Also interesting:

What is now a folkloristic spectacle for locals and tourists alike had its bloody origins at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1807, Copenhagen was besieged by the British and mercilessly bombed to rubble. The Danes not only had to look back on their destroyed capital, but also had to watch as the British confiscated their entire navy and destroyed all ships under construction. In addition, countless merchant ships were confiscated, on which rigging, canvas and cannons were taken away. The Scandinavian kingdom no longer had any means of protecting its trade and maritime territory; the proud seafaring nation was a mere shadow of its former self.

Resentment towards the English united all

But there was no question of the humiliated Danes surrendering completely to their fate. The brilliant idea came from their arch-enemy Sweden, of all places. There, gun sloops and dinghies were deployed in the wounded archipelago waters, which could be rowed and sailed. The emergency solution quickly found favour and so it was that an armada of around 250 of the Lilliputian warships was launched in the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway over the next few years. These sometimes had martial names such as "Sejr og død" (Victory and Death). All sections of the population contributed to the realisation. Queen Marie, for example, donated half of her pin money, large landowners sent not only money but also suitable oak trees from their forests for the construction, and even the smallest contributions from the poor were welcome. The large shipping companies donated several fully equipped boats. Resentment towards the thieving English united them all and the so-called "Gunboat War of 1807-1814" was born.

The English naturally mocked the "ridiculous poor navy", but were nevertheless forced to allow their merchant ships to sail in the Danish-Norwegian waters in escorted convoys. During the seven-year "gunboat war", the Scandinavians managed a few spectacular pinpricks. As early as 1808, the first war brig, "The Tickler", was captured in the Langelandsbelt. Seven more British naval brigs and a considerable number of merchant ships were to follow.

The golden rule of guerrilla tactics was that one gunboat was never allowed to operate alone. At least two boats had to work together, preferably several. The biggest advantage of the small boats with 18 oarsmen was obvious: they could also operate in light winds and calm conditions when the tall ships were more or less unable to manoeuvre. They attacked the enemy ships from an acute angle to the bow or stern so that they themselves could not be shot at from the broadside. When a gunboat reached its ideal attack position, the boat was turned 180 degrees so that the stern cannon could be fired. Fine adjustments were also made with the boat itself. If the wind suddenly picked up again, they would quickly seek refuge in the shallower waters, which were out of reach for the large ships.

"Corsør" true to the original - except for two electric motors

A gunboat like the "Corsør" could carry 160 cannonballs and 30 canvas bags filled with iron waste. There were also 1,340 pounds of black powder stored on board for firing, which had to be kept dry at all costs. A well-rehearsed crew was able to fire one shot every three and a half minutes. This was certainly not much compared to the firing power of a fully equipped warship of the British navy. On the other hand, the agile dinghies lying flat on the water were difficult to hit, especially when they were close to the enemy. The guns on board were simply not designed or positioned to fend off the ships attacking from below.

In addition to the heavy stern gun, the warships were also equipped with smaller swivelling, side-mounted cannons. There were also plenty of small arms and grappling hooks, which were ultimately needed to capture an enemy ship.

Another advantage of the miniature fleet was the simple logistics. Repairs could be carried out in almost all harbour towns. Provisions and water could be easily obtained and taken on board anywhere on the coast, as could replacements for injured or fallen crew members in the form of fishermen or farmers. Ammunition could also be stockpiled at the 114 redoubts and batteries dotted around the country.

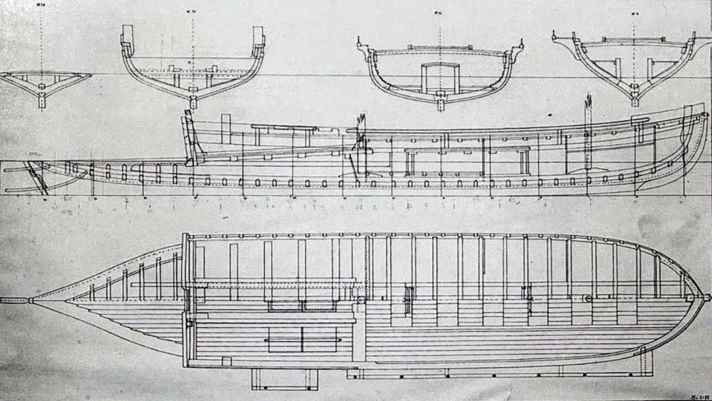

Back to the present. Every trip on the "Corsør" gunboat begins with the command "Ready on deck - row away!". It took three years to raise the funds and another three years to build. Everything is true to the original - except for the two electric motors, which can be used silently and invisibly for harbour manoeuvres.

Young people build the "Corsør"

The rest of the work is done by the pupils from the Korsør production school, who are full of vigour. "These are young people who have fallen through the cracks of the traditional school system," explains commander Christian Dyrløv, who grew up on Greenland. He is also the manager of the affiliated shipyard where the "Corsør" was built by schoolchildren, apprentices and a few professionals. Their motto "The young people build the boat, while the boat lets the young people grow" seems to work in practice too. Their faces reflect pride as well as a sense of responsibility and joie de vivre.

An oversized Dannebrog, the Danish national flag, flies from the stern. The XXL flag was intended to win the respect of the enemy and serve as an encouragement for the crew and population alike. When the 24-pounder is deployed, however, it hangs in the way and has to be retrieved. Then the 82-year-old Klavs Flittner, alias "Kanonkongen" (Cannon King), comes into action. As the name suggests, he is responsible for firing the two-tonne gun on the "Corsør". However, his title is not of a historical nature, but a nickname referring to his petite figure and height of just 155 centimetres. In the past, cannon kings were small men who were put into cannons at fairs and then shot out.

Flittner, whose family emigrated from Thuringia to Denmark in 1750, has been shooting historical weapons for over 40 years. In an accident with a muzzle-loader, he shot himself through one hand. Since then, both palms have been speckled with black powder stains - a kind of tattoo that reminds him for the rest of his life that his love of the old guns comes with certain risks. Incidentally, he came up with the idea of building the gunboat. The incentive doesn't seem to have been entirely altruistic either, as the big gun is the biggest weapon Flittner has been allowed to fire in his career. At least until today.

Of course, the mini three-master can also sail

Probably the ship's greatest technical feature is the four-metre-long platform that extends the stern to the waterline. It is not used by the exhausted crew for a refreshing swim break, but rather balances out the weight of the cannon, which weighs several tonnes, by providing additional buoyancy. The fact that the provisions box was stowed under the cannon proves that the well-being of the crew of 24 was of secondary importance at the time. In order to satisfy their hunger, the cannon sledge had to be moved, which made it impossible for the men to eat or even drink on the sly. Not that dry bread, salted meat and fish were considered a delicacy, but at least there was brandy and beer on board. Not only did they last longer than water, but it was also good for morale.

And that was immensely important, because life and fighting on the open boats was brutal and exhausting. They were often at sea for weeks at a time, constantly exposed to the elements. While the officers slept cramped but at least under the running deck, the rowers lounged on deck in the open air.

Of course, the almost 15 metre long mini three-master can also sail. The lugger rig with foresail, two square sails and the mizzen is considered to be the largest of its kind in Denmark. On the longest trip to date from Lolland to Korsør, the boat managed to sail up to 40 degrees to the wind. "If we move the moorings for the headsail's hoisting points even further aft, we could go even harder into the wind," explains shipyard manager Dyrløv as he gives the command to set sail.

The fastest the ship sails downwind is up to six knots. Further records are not expected, as the "Corsør" is not suitable for sailing in rough seas - and it is not allowed to do so. This has been determined by the Danish Maritime Authority (Søfartsstyrelsen), also based in Korsør, which has approved the ship. From a wind force of ten metres per second or a wave height of 75 centimetres, the gunboat may no longer leave the protected harbour area. This makes perfect sense, as the "Corsør" only has two scuppers aft, where any excess water can run out again. Should a wave nevertheless come in or leakage occur, manual and automatic bilge pumps are installed in accordance with safety regulations. Rowing with the oars, which are a good five and a half metres long, is also hardly possible in correspondingly high waves, as they are then literally rowing in the air.

Red thread in cordage for theft protection

A 120-kilogram diesel fire pump can suck up 15 cubic metres of extinguishing water per hour in the event of a fire. Last but not least, every crew member must have a lifejacket to hand. "The strict requirements exist because we are authorised to take on passengers. In the past, of course, none of that mattered - we used to go out whenever the enemy appeared near the coast," says boat builder Kristian Jakobsen. The shipyard manager's former apprentice is the only permanent employee. All the others are either students or voluntary pensioners who enjoy living history and the community. The historical uniforms that are worn on all ceremonial outings were also sewn by volunteers.

Greifswald sailmaker Sebastian Hentschel organised a workshop for the students on sewing the sailcloth. German production students also came to Korsør to take part in the construction through the EU's Interreg funding programme. Traditional boat building brings people together.

There is no room for a tiller due to the guns and the associated propulsion. The rudder, which is mounted at the very back of the extended underwater hull, is moved with a cable system whose guide line is located in front of the mizzen mast above the cannon. However, there must be room for a life raft, which conveniently also serves as a seat for the helmsman.

Incidentally, all the ropes on board were made by a local rope maker. The Danish king used to have a red thread woven into the cordage of his ships. It was of a superior quality to standard ropes and was therefore much sought after by thieves. If a marked rope was found on a civilian ship, it was clear that it must have been stolen from the royal navy. The punishment was draconian and could cost you your head in case of doubt. "But the English had the same markings," laughs Dyrløv, "which of course came in very handy when they seized our fleet!" What has remained is the expression "red thread", in which a recognisable order in a matter is followed through from beginning to end.

600 grams of gunpowder per shot

Even though the ropes no longer need to be secured against theft, the extremely restrictive weapons legislation in Denmark means that weapons and ammunition of all kinds must be specially secured or made inaccessible to unauthorised persons. The unstable gunpowder is stored in a safe on land and the cannon, which should be difficult to steal due to its weight of several tonnes, must also be secured - otherwise it would have to be moved to a gun cabinet at night. However, the authorities only need a leather strap that is locked to the boat and stretched over the cannon. Better safe than sorry - even if it has more of a symbolic value in this case.

Furthermore, each individual cannon shot must be registered in advance, stating the time and firing area. Today, 600 grams of gunpowder are fired per shot, which costs the equivalent of around 135 euros. In the past, three kilograms of the explosive powder were needed to send a twelve-kilogram iron ball flying. Today, only a ten-metre-long jet of flame comes out, but even that is a fire hazard should someone stray into the muzzle flash. Apart from the "gun king", only the two other "officers" on board, Dyrløv and Jakobsen, are authorised to operate the gun. In the gunpowder chamber amidships, where the gunpowder was stored in the 19th century, there are now 16 batteries that power the two electric motors when required. This is the turn of an era on a warship.

Students, boat builders and volunteers gather for a coffee break in the group room of the shipyard, which lies in the lee of the old ski jump. A rowing boat hangs keel-up above the table. Below it dangle the severed heads of various seabirds. "It was a crazy idea," explains Dyrløv apologetically. He had found the dead birds and taken them with him. "This is our oracle for the weather, depending on how the heads turn." A weather model as bizarre as the gunboat, which fits.

Technical data of the "Corsør

- Shipyard: Korsør Production School

- Launching: 2019

- Material/construction: Larch planked on oak

- Total length: 14,56 m

- Width: 3,00 m

- Depth: 1,13 m

- Mast height main mast: 8,10 m

- Max. sail area: 60,53 m²

- Weight: 7,5 t

- machine (E-Torqeedo Cruise): 2x10 kw

Morten Strauch

Editor News & Panorama