Due to the large width and the small and short keels and the associated small lateral area, sailing high upwind is not really one of the strengths of a cat. Many examples only reach a height of around 60 degrees upwind. The true strengths of these boats, on the other hand, lie in their shape when sailing downwind. In this case, the wide beam enables upright sailing and the small wetted surface under water offers little resistance. The cat is at home on a cross-wind course.

However, the deeper the course, the weaker the sail performance, because the small self-tacking jibs of modern cruising cats then quickly reach the cover of the mainsail. Crossing before the wind can be an option in this case to keep both sails full and the ship balanced on the rudder. A cross course can lead a cat to its destination much faster. On courses with a wind angle of 150 degrees, the ship will cover around 15 per cent more distance, but in a significantly shorter time than flat before the sheet. On long crossings, however, it is sometimes tedious to jibe regularly.

If there is only one cloth in the wind, the catamaran sails unbalanced. Only under mainsail and therefore with the sail pressure point very far aft does the boat always have a tendency to turn aft, and both the autopilot and the rudder blades have to absorb large forces to counteract this. Retracting the mainsail completely and sailing with only the headsail is an option that some cruising sailors choose, even across oceans. However, the small genoa - or often even just a self-tacking jib - on modern catamarans makes it almost impossible to reach acceptable speeds. Such ships are not designed to sail with just one sail.

The right sails for the right conditions

Modern cruising catamarans are heavy due to the large amount of living space. Especially in light and aft winds, which reduce the apparent wind on board even more, they are difficult to get moving. But even in normal conditions, it is helpful to have a suitable sail on board for every wind angle. The large width of the boats with a good sheeting angle and a large stability range makes it possible to set large sails - which is why the range is also bewilderingly extensive.

Choosing the right sail is not easy. Regardless of whether you are an owner equipping your first catamaran for a long voyage - or a charter sailor considering booking an extra sail for an additional charge. In light winds, you want to be faster with such a sail. But at the same time, there is basically no point in having the fastest and largest sail on board if the crew rarely unpack it for fear of its size or the inconvenience of setting it.

Easy handling is therefore an important criterion. If, for example, an asymmetrical spinnaker with a snuffer can be easily recovered as soon as it is folded into the lee of the mainsail and can be recovered with the sock, then recovery on a long voyage can become a major operation if the mainsail has not been set and the snuffer cannot be pulled over the bulging sail.

Spoilt for choice

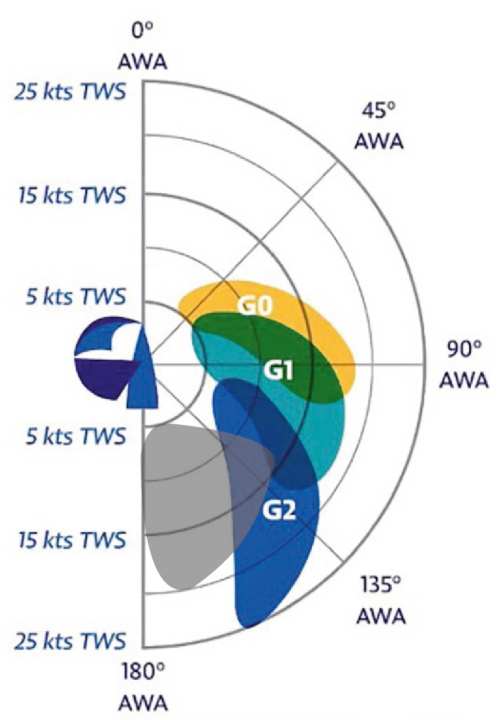

There is a whole range of headsails available for a catamaran, from the flat-cut Code Zero, which is intended for courses above half-wind, to the lighter gennaker, a slightly more bulbous, asymmetrically cut spinnaker for more spacious courses, to the symmetrically cut spinnaker or a wing spinnaker (e.g. Parasailor from Istec or Levante from Oxley) for very deep courses.

The more bulbous the sails, the better for aft winds. While the Code Zero still has the function of a hydrofoil with a current on both sides, the symmetrical spinnaker is spread out in front of the mast to catch as much wind as possible.

The differences between the sails can be measured with the help of a value: The largest width (SMW value) of the sail is measured at half the length of the luff and then compared with the length of the foot. A Code Zero, for example, has a width of around 60 to 75 per cent of the lower luff length and is therefore extremely flat. This means that a relatively small angle to the wind can be achieved with this sail (60 to 110 degrees apparent wind). It is easy to operate and is usually used with a furling system. In addition, the sail can be equipped with UV protection, which, in combination with its small packing size, makes it possible to sail the sail permanently furled.

Since the sail is used to sail sharp courses to the wind, it is also subjected to relatively high loads. This is why polyester cloth, laminates or even membranes are possible materials. The Code Zero is actually an upwind sail, but due to its multifunctional nature and size, it is also a sail that can be sailed by the cruising sailor even into the room wind range if an even larger, lighter and more bulbous cloth is not available.

Use of spinnaker and gennaker

Asymmetric spinnakers or gennakers have a width of around 80 to 105 per cent of the downhaul length and are therefore significantly more bulbous, making them more suitable for courses with more aft winds. Depending on the sailmaker, the designations, cuts and sizes of the sails for use in regattas change in five to six stages. For the sake of simplicity, we divide them into two variants for use in cruising sailing: flatter for more acute angles and more bulbous for deeper courses.

Their optimum range of use is at a wind angle of between 100 and 155 degrees (apparent wind). Depending on the size, angle of incidence and loads, nylon or polyester is chosen as the material. The choice of material weight depends on the desired cut and the angle to the wind. For a somewhat flatter sail, the material must be somewhat thicker, but the sail can be ridden on a furling system - and the larger and more bulbous the sail is to be in order to reach deeper courses, the thinner the material can be. However, very bulbous sails are more difficult to furl and it may then be necessary to furl them in a furling tube. A symmetrical spinnaker is very rarely found on a cruising catamaran, although it can even be sailed without a spinnaker pole due to the large width of the boat.

Sometimes it makes sense to sail without a main

If a catamaran has so far only been sailed with a mainsail and genoa and is not yet designed by the shipyard for additional space wind sails, a code zero can initially be a good compromise, on the one hand to be a little faster downwind and on half-wind courses, but on the other hand to have more options for space wind courses due to its size. Of all the options, the Code Zero is the most stable and easiest to handle sail that doesn't get damaged so quickly. If it is equipped with UV protection and is furled on a gennaker pole, it does not have to be recovered immediately after every use like a UV-endangered gennaker.

Especially on deep courses, where the mainsail would cover the headsail, it may be advisable not to set the mainsail at all. However, the manual should be consulted beforehand to ensure that the catamaran's rig is suitable for sailing without a mainsail. This is because some rigs require the additional stability of the mainsail, otherwise there is a risk of the mast breaking. On a catamaran, it is always important to secure the boom with a bullstander when sailing a rough course.

Unlike a monohull, which rolls dynamically from one side to the other on courses with a tailwind due to its shape, a catamaran can tend to roll due to the sails dancing from one side of the mast to the other, but then, due to its large width and the resulting dimensional stability, it can jerk hard instead, causing the boom to swing from one side to the other. It should therefore always be secured and not be able to move.

Fixed attachment points for space wind sails on catamarans

Also unlike the mono, it is rarely necessary to furl the mainsheet downwind. With a traveller that is often six or seven metres long, it is perfectly sufficient to drive the car completely to leeward. In this case, the boom is only at an angle of 45 to 55 degrees from the centreline to leeward - but the mainsail will already be leaning against the upper shrouds in the upper area - which is already too much, because it will chafe against them. If a bull stander is then led from the boom clew to the midship cleat and pushed through, the boom is well secured.

On the other hand, there are optimum conditions for attaching the space windsail if there is a trunk attached from the shipyard as a stationary bowsprit. Such systems are also available for retrofitting, for example from the American manufacturer Forespar (German dealer: Sailtec, price: between 1,000 and 1,400 euros). They are relatively easy to install, are simply riveted to the front beam and are braced downwards towards the hull with water stays made of wire or Dyneema and Padeyes.

The disadvantage of such a fixed anchor point is that the sail can quickly get into the cover of the mainsail on very deep courses and then collapse. This can be prevented by avoiding particularly deep courses and by ensuring that the catamaran is practically always tacking downwind.

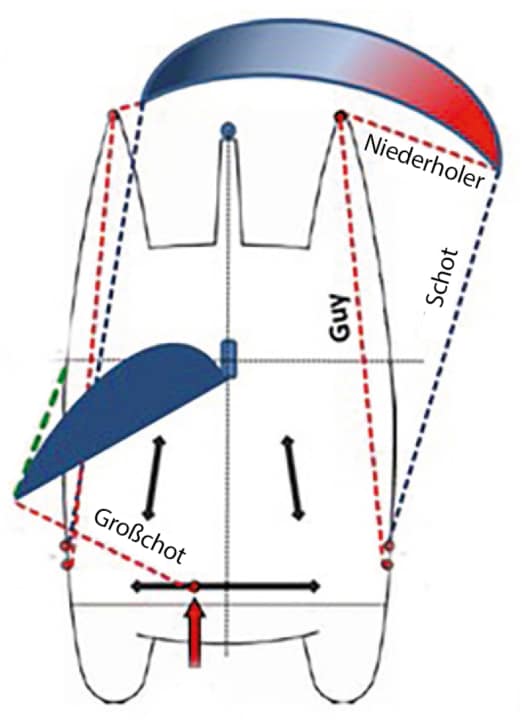

An alternative method of attachment is to fit a long line with an eye and snap shackle in the centre and guide it through pulleys to both bow tips and aft onto the superstructure. The neck of the asymmetrical spinnaker is then attached to the snap shackle. In this way, the attachment point of the spinnaker can be moved back and forth on the beam, either to windward (for low courses) or towards the centre (for higher courses). In the centre position, angles of up to 135 degrees to the apparent wind are possible, with the windward position even 135 to 160 degrees. However, jibing is somewhat awkward with a sail attached so close to the forestay.

Catamarans tend to undercut

Both a winged sail and a normal spinnaker are each rigged with four lines. Two sheets on the clews, which are guided around the outside of the shrouds to the aft onto the deflection blocks mounted in the last third of the ship, and additionally two barber haulers/lower haulers, which also attach to the clews and are guided to the aft by vertical deflection blocks mounted on the bow tips. In this way, it is possible to keep the sail open and bring it to windward due to the large width of the catamaran and without the use of a spinnaker pole. Jibing is also made easy because there is no need to hoist a spinnaker pole, the sail simply swings through to the other side in front of the forestay.

Catamarans have one disadvantage due to their high speeds and narrow bow tips with little buoyancy: they always tend to undercut. While regatta and beach catamarans run the risk of capsizing over the bow, this does not happen with cruising catamarans due to their high weight.

However, it is quite possible for the bow tips to be submerged in the waves up to the superstructure and for the deck to get wet. Wingsails have a very helpful advantage, especially on a catamaran, because these cloths not only provide propulsion but also buoyancy due to their wings and generate a considerable pull on the barbers, which engage with blocks on the bow tips. The Parasailor therefore exerts a constant pull on the bow tips of the catamaran and lifts them slightly, which minimises the risk of undercutting in the waves.

Be careful with too much wind

There is another special feature on spacious courses. It is difficult to estimate when it will be too much for the colourful cloth. The most important instrument on a catamaran - on any course to the wind, by the way - is the anemometer. Unlike a monohull, a catamaran does not draw attention to itself by heeling more strongly when the pressure in the rig becomes too much. It counteracts this with its wide hull and high righting moment until it breaks.

Similarly, on a downwind course it is difficult to judge when it is time to reef the sails. If a catamaran is surfing down the wave crests at ten knots before the wind and only a medium apparent wind of 15 knots can be felt and measured on board, then a true wind of a good 25 knots is blowing. That may still feel okay. But at the latest when the apparent wind of 20 knots gives you the urgent feeling that you have to lower the sail, then it is already blowing at 30 knots, and every luff can become extremely dangerous because the apparent wind increases with every degree of wind ahead.

With an extremely light multihull, it can also happen that the boat overtakes its own spinnaker when surfing from the wave crests due to the sudden acceleration, which collapses due to the reduced apparent wind and wraps itself around the forestay.

There is no one cloth for every purpose, sailing style and sailing area

If you already have a little respect for setting the big cloths on long journeys, you would be well advised to adjust the sails to the maximum expected wind from the outset. A fully battened mainsail can hardly be reefed before the wind, because the battens then rest against the shrouds. For this reason, the sail area should be reduced from the outset on long journeys, at night and in unstable conditions. If the mainsail is already in the second reef, the asymmetrical spinnaker can simply be furled away when the wind picks up.

There is no one cloth for every purpose, sailing style and sailing area. If you are mainly sailing in the Baltic or the Mediterranean, the Code Zero is a good choice for sailing between courses with a chop in the sheets and slightly astern as a cross-sail. In addition, a rather bulbous asymmetric spinnaker that covers the connection area up to the rough wind and also works almost exactly downwind with a sail neck shackled to the windward hull.

If, on the other hand, you want to sail around the world, a code zero or gennaker and also a wing spinnaker are the perfect choice. For the most part, you will be travelling long distances in a trade wind, and this is when the wingsails with their wide range of use and great strengths come into their own on very deep courses.