Record attempt: Craig Wood becomes the first triple amputee to attempt a solo trans-Pacific journey

Fabian Boerger

· 26.03.2025

It takes around 80 days to cross the North Pacific in one go. While blue-water sailors travel from archipelago to archipelago south of the equator, possible stopovers in the northern hemisphere are much rarer. In short: the 7,000 nautical miles from the west coast of Mexico to Japan place high demands on the boat and crew. High waves, strong storms and long lulls are constant companions. They require plenty of courage, endurance and seamanship.

Pacific passage: solo and non-stop

All the more astonishing is the endeavour of Briton Craig Wood. He wants to attempt the two-and-a-half-month crossing solo and non-stop. That alone would be a remarkable achievement. But as if that wasn't enough, the 33-year-old is also attempting the voyage despite being missing one hand and both legs.

With his solo journey across the Pacific, he is not only pursuing the goal of setting a record - he would be the first triple amputee to achieve this. Craig Wood wants to prove what people with disabilities can achieve. "Many people believe that someone without legs cannot sail such a distance. I want to show that it is possible," says Wood.

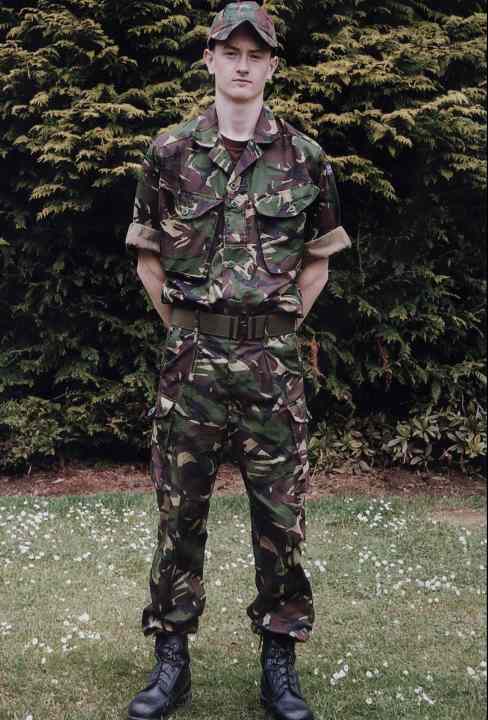

As a soldier in Afghanistan

Flashback. Shortly after his 18th birthday in April 2009, Craig Wood is deployed to Afghanistan. He has always been an adventurous person, he says. That's why he made a conscious decision to join the army. He became a soldier in an infantry unit. It was supposed to be his chance to travel the world. But then came 30 July, which completely changed his life in one fell swoop.

It is late afternoon. Wood is on patrol with his unit - eight men of a similar age - in Helmand Province in the south of the country. After a while, they stop for a quick drink of water. When they set off again five minutes later, ten steps later, it happens: a so-called IED, a booby trap, explodes under Wood's feet. He says he saw a white flash in front of him when he recounts the accident. Then he was knocked to the ground. He heard a comrade calling for him. Then silence fell over him.

More than four years of rehabilitation

It was not until two weeks later that Wood woke up in hospital in Birmingham from the coma he had been placed in due to his serious injuries. Both legs were amputated and his left hand was missing. Shrapnel has severely injured his face and shrapnel has caused wounds all over his body.

It takes over seven months before he can walk again. Around 20 operations are necessary. He spends around four years at Headley Court, a rehabilitation centre for injured soldiers in Surrey in the south of England. "I would say it took me about a year and a half to fully accept what had happened. I went from being an 18-year-old in his prime to a man in a wheelchair, and that had a big impact on my psyche," says Wood in an interview with the British magazine "Yachting Monthly".

Sailing - an integral part of Craig Wood's life

His family gave him strength during this difficult time, he says. They encouraged him to make the best of his situation. While he was still in hospital, his father contacted a coach from the British Paralympic team. Shortly afterwards, Wood is sitting in a rubber dinghy in his wheelchair, accompanying the Paralympic sailors during training. It is a turning point in his life.

His father's initiative was no accident; even before the accident, sailing had a firm place in Woods' life. Growing up in Doncaster, east of Manchester, he learnt how to handle the tiller and sheet from his father. At first he sailed in an optimist off the coast of Bridlington, later switching to windsurfing.

Before the long haul, the Paralympic career

Today, sailing gives him the feeling of being equal to other people despite his physical limitations, as he says. "It's something that was part of my life even before the accident." In 2012, Wood began sailing regattas in the 2.4mR, a boat class for people with disabilities. Two years later, he met Steve Palmer, who had also lost both legs, and the visually impaired Liam Cattermole. From then on, they sailed together in the Sonar class with the aim of taking part in the 2016 Paralympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

But things turn out differently. The trio missed their chance to participate and were denied a second opportunity. Shortly before the 2015 Games, the Paralympic Committee announced that sailing would lose its participation status. The official reason given was that the sport lacked international recognition. A bitter setback not only for the British trio, but for all the athletes concerned. However, while one dream is shattered for Craig Wood, another opportunity opens up for him almost simultaneously: he sails on a yacht at the Para World Championships in Melbourne - and then has the idea of sailing around the world.

Craig Woods starts circumnavigation in 2017

The idea was quickly followed by action, and it wasn't long before Wood bought his first boat: a 40-foot, ketch-rigged Colvic Victor motorsailer. He spent a year overhauling the old boat. He learns to navigate, gains his first experience of cruising and finally sets course for the Mediterranean in April 2017. It was the beginning of his circumnavigation, which continues to this day.

However, the motorised sailboat only accompanies him as far as Greece. The boat is too cumbersome and he has to motor too often. A better sailing alternative was needed. On Lefkada, in the west of the country, he comes across a Beneteau Oceanis 46, with which he sails from Greece via Sicily to Barcelona and on to Gibraltar.

Travelling together to South America

On some legs he is travelling single-handed, on others he is accompanied by fellow sailors. He also regularly takes backpackers with him. Once, as he recounts in an interview, he had eight German-speaking backpackers on board at the same time. One of them is Renate Gwerder from Switzerland. She is backpacking and wants to travel the world. Her destination: South America. Gwerder doesn't just stay for the evening, she is still at Wood's side today. They now have two children together and are married.

From Gibraltar, they continue westwards together. They then make the leap to the Cape Verde Islands before sailing across the Atlantic and heading for Brazil. There, they make their way south along the coast and sail on via Argentina and the Falkland Islands to Tierra del Fuego. They cross the Beagle Channel and then head north to Central America.

Lessons from travelling the world

"Sailing in the Mediterranean, across the Atlantic and around South America has taught me a lot. One realisation was that it's important to speak the language of the country you're in. Then there are no problems with visas or the like," says Wood. He also learnt to be flexible when it comes to making appointments and meeting deadlines. "In many other countries, you can't have the expectation that there are binding time agreements like there are in Europe," says Wood.

The couple spent several years travelling along the Central American coast. They visit Ecuador, Panama and Mexico. There they sell their "Sirius" at the end of 2022. But their time without a boat was short-lived. A few weeks later, they found a new home for the next stages of their round-the-world trip: They buy a Galileo 41, an aluminium catamaran from France, which they christen "Sirius II".

Travelling on two hulls instead of one

In Panama, they set up the boat for the now small family and make preparations for the upcoming Pacific crossing. Numerous handles are fitted on board. He also has access to electric winches for trimming and setting the sails. They make everyday sailing much easier for Wood. In addition, the deck of the cat has been fitted with a particularly non-slip coating. This is crucial, as his prosthetic legs give him sufficient grip even in wet weather or rough seas.

His impairments are particularly noticeable when the waves and wind cause the boat to roll, says Wood. It is particularly difficult for him to walk across the cabin roof when he has to work on the mast or reef the sails. "It's then even more difficult for me to keep my balance and hold on, especially as I'm also secured with the lifebelt, which further restricts my freedom of movement," explains Wood. But even seemingly trivial skills such as descending the steep, narrow steps into the cabin or closing a shackle sometimes present Wood with challenges. He has learnt to master these in recent years.

"Don't use disability as an excuse"

Despite this, he always finds a way; he can now do a lot of things with just one hand, such as tying a bowline. "I can't use my disability as an excuse," he says. He also plays the ukulele, goes kitesurfing and tried horse riding in Patagonia. And he is the first person with this type of physical impairment to hold a Yachtmaster licence - an internationally important certificate for professional skippers. "Every day I learn something new; bit by bit I'm getting a little bit better." He takes a pragmatic approach to problems: "I do it like everyone else," explains Wood, "I just solve one problem at a time."

Wood set off on his Pacific crossing at the end of March. He wants to sail non-stop and unsupported from Puerta Vallarta in Mexico to Yokohama in Japan. With around 7,000 nautical miles and around 80 days at sea, it is the longest crossing for the Briton to date. Should something break on board, he is keeping open the option of making a stopover on the Hawaiian Islands. "The aim is to reach Japan at the end of May or beginning of June," he says.

Transpacific: More than just another stage

The sooner the better is the motto. Because the longer it takes to complete the route, the more it will be caught up in the typhoon season on the Pacific. This begins at the end of May and lasts until November. However, tropical storms can also occur outside of these months, which could affect its route. Overall, conditions are likely to become more unstable once it has left Hawaii behind and is travelling to higher latitudes.

For Craig Wood, the crossing means more than just another leg of his circumnavigation. With this journey, he wants to inspire people who have been through tough times, especially veterans with similar experiences to his own. "It's definitely a drive and a reason for doing what I'm doing," he says.

Giving something back

During his travellinge collects donations via a crowdfunding pagewhich benefit the British charity organisations "Blesma" and "Turn to Starboard". They support veterans who have to live without limbs and those who need help with reintegration. The organisations have also helped Wood get back to life.

This is another reason why the 33-year-old plans to set up his own charity organisation one day, which will also support veterans. With the help of sailing, he wants to show others how they can find their way back to life - just as he did.