Text by Till Hein

"I have no special talent," wrote Albert Einstein in a letter in 1952, "I am just passionately curious." Whether he was right in this assessment remains to be seen. In any case, his discoveries on expeditions into uncharted scientific territory were spectacular. The rector of Princeton University in the US state of New Jersey ennobled him as the "new Columbus of science, sailing alone through the strange seas of thought" when he awarded him an honorary doctorate in May 1921. A beautiful maritime metaphor - but one that only tells half the story.

Read also:

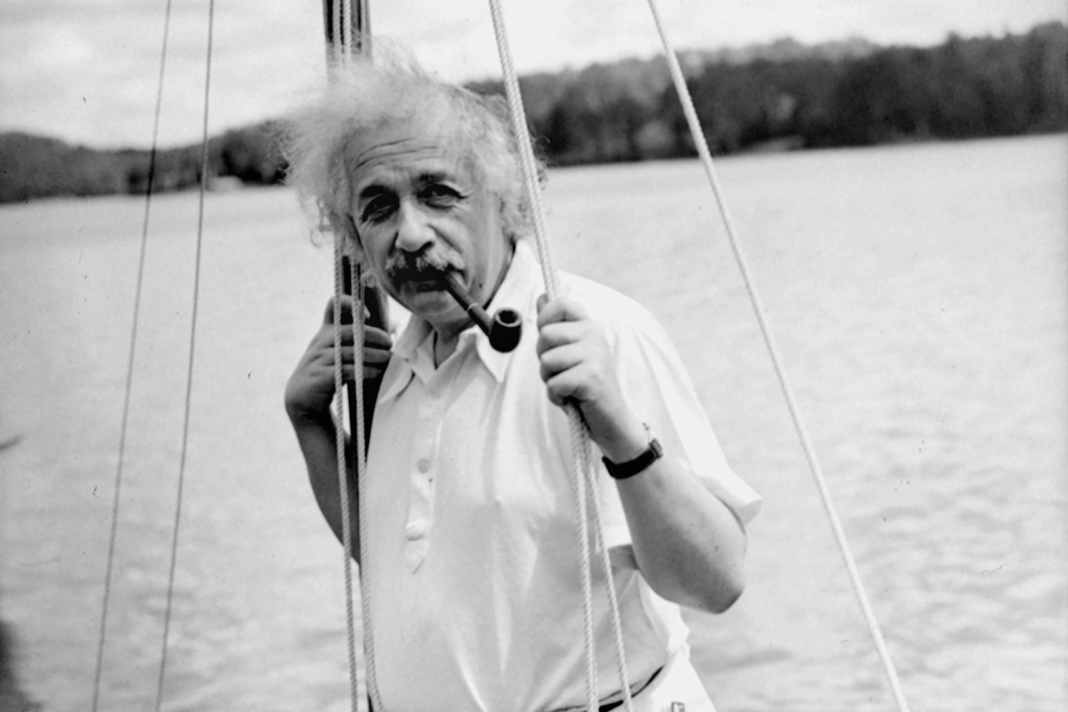

In reality, Einstein by no means sailed exclusively through the "seas of thought", and he was rarely alone on his cruises in the material world. He liked to invite attractive women or good mates along. "The joy of this activity is written all over his face," said his son-in-law Rudolf Kayser around 1930. "It echoes in his words and in his happy smile."

Einstein carries a notebook on board the dinghy

Einstein really enjoyed sailing. And that's not all: when there was no wind, he often took notes or enthusiastically shared his latest ideas on the basic laws of physics with his fellow sailors. "It is impossible not to speculate about how much of the theory of relativity Einstein may have come across on sailing trips," writes the US trade journal "Good Old Boat Magazine". This is probably also because insights are often not gained while pondering alone, but while trying to convey one's thoughts to others.

Albert Einstein learnt to sail on Lake Zurich at the end of the 1890s. He was young and studying physics at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic (now ETH Zurich). He spent as much time as possible on the water with Susanne Markwalder, the charming daughter of his landlady. He always carried a notebook with him on board the dinghy, his sailing partner writes in her memoirs. When it was calm, he would take it out and scribble away. "But as soon as there was a breath of wind, he was ready to sail again."

In letters to friends at the time, he also mentioned his preoccupation with a revolutionary idea that would change the "theory of space and time". So perhaps it is no coincidence that the crucial starting point of his theory of relativity can be easily explained using the example of a boat on the water: Suppose a yacht is gliding along at a speed of 20 knots - i.e. 37 kilometres per hour - and a passenger is jogging on board at a speed of ten kilometres per hour in the direction of travel. The speeds of the boat and the runner then add up. Viewed from the shore, the runner has a total speed of 47 kilometres per hour.

However, if the person on board now sends a beam of light in the direction of travel instead of jogging, then this beam itself has the speed c (speed of light) - and intuitively one assumes that, viewed from the shore, it has a total speed of 37 kilometres per hour + c must have. That sounds logical - but it is wrong: in reality, light always remains the same speed, regardless of whether it is sent from a fixed location on land, from a gently gliding sailing yacht or from a speedboat shooting across the water. Nothing adds up - a beam of light always maintains exactly the same speed, even when travelling in the direction of a racing yacht (or other very fast means of transport) c. The speed of light.

Milestone for physics

Numerous experiments have since shown that Einstein was also correct with his revolutionary conclusions about the constancy of the speed of light. And his special theory of relativity proves such curious things as the fact that there is no equally valid answer for all observers to the question of whether two events take place in different places at the same time or at different times. Or that an astronaut who flies through space in a spaceship for a year is younger on his return than his twin brother who stayed on earth.

"Einstein's findings established a completely new interpretation of space and time: in fast-moving systems, time appears to slow down and distances shrink," says physicist and Einstein expert Sönke Harm from Kiel University. "And the extension to the general theory of relativity, in which Einstein extended his considerations to space filled with masses in 1916, will make it possible in the 21st century to determine precise locations using GPS, among other things."

Albert Einstein was not only fascinated by the element of water when sailing. As a scientist, for example, he fathomed the physical laws that make rivers meander and investigated the capillary forces that enable trees to channel nutrients from the soil into the branches of the crown. Even the movement of dust on water droplets stimulated his ambition. The Scottish botanist Robert Brown had observed this phenomenon under the microscope, but was unable to find an explanation for it. Albert Einstein was different. In 1905, he published a paper on this nerdy subject.

Based on the statistical theory of heat, he recognised correlations between the distance travelled by a particle over a period of time, the temperature and viscosity of the liquid and the radius of the particle. His study also provided empirical proof of the existence of atoms (the smallest particles of chemical elements), which had previously been disputed by many experts. A milestone for physics.

Development of the Anschütz compass

At the time, Einstein was working as a "third-class technical expert" at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. As he had not been a diligent student, he had not found employment as a scientist. But 1905 became his "miracle year". In addition to the study on dust on water droplets, he published four other papers, including his first on the theory of relativity: a study of just 9,000 words that contained no footnotes or references - and laid the foundation for his rise to global scientific stardom.

The scientist who loved sailing so much also carried out applied research: between 1915 and 1927, Einstein worked with the inventor and entrepreneur Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe from Kiel, who wanted to travel to the North Pole in a submarine, on a new type of compass that would be reliable regardless of the Earth's magnetic field. Initially, Einstein acted as an "impartial expert witness" for the company Anschütz & Co. in a patent lawsuit. Based on his expert opinion of 7 August 1915, competitors were banned from continuing to manufacture compasses based on this principle under threat of fines and prison sentences. A US company had to pay three million marks in damages.

Albert Einstein, in turn, who was appointed as a researcher at the renowned Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin in 1914, was so fascinated by the concept of the Anschütz compass that he began to correspond with its inventor about improvements - whereupon a close friendship developed between the two men. In September 1920, Einstein gave the decisive tip for a technical improvement to the ball bearing.

Completion of the considerations on the general theory of relativity

From 1923, he even had a small official flat available in Kiel, which he called his "Diogenes Tonne". It was small, but had direct access to the water. Einstein spent many summers together with Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe and sailed with him on the Kiel Fjord. In 1926, a licence agreement was signed that guaranteed him one percent of the sales price of every Anschütz compass. And the invention caught on: French, American and German warships, but also huge ocean liners such as the "Bremen" and the "Europa" were equipped with such devices. At the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, where he worked until 1932, Einstein completed his work on the general theory of relativity - which expanded the spectacular 1905 essay into a more comprehensive concept.

"Even for Einstein himself, these considerations were initially somewhat surprising and ultimately led to a completely new description of the phenomenon of gravity, in which the gravitational force so successfully introduced by Isaac Newton 250 years earlier was replaced by a property of space and time. "Space and time can therefore no longer be considered separately and are also curved wherever there are large masses such as celestial bodies," says physicist Sönke Harm from Kiel University.

The wet element never lets Einstein go

Albert Einstein recuperated from his mental exertions as often as possible on the lakes in the Berlin area. "He hoisted the sails himself, climbed around in the boat to tighten the ropes and lines, and handled poles and hooks to get the boat off the shore," reports his son-in-law and biographer Rudolf Kayser. Even as a researcher, the wet element never left him: for example, the wife of a colleague once wanted to know why, when you stir tea in a cup with a spoon, the tea leaves always collect in the centre of the bottom. Einstein came up with the following explanation: the stirred tea turns fastest in the centre of the cup. "The tea leaves are carried towards the centre of the cup by the circulating movement," says Einstein. And due to their weight, they remain at the bottom in the centre.

The physicist took the considerations further: he realised that the flow velocity in a river bed is also lower at the bottom. If the water runs towards the outside of a bend, it dips there, as it were, and returns to the inside via the bottom, Einstein wrote in a scientific paper in 1926. This also results in a circulating flow. The outer bank is virtually eaten away, its material washed away. On the inside of the knee, on the other hand, more and more sediment is deposited, the river slows down even more there - and every river that is not locked in a corset of concrete meanders along.

As virtuously as Albert Einstein analysed such forces, waves, wind and weather sometimes caused the passionate sailor great problems in real life: The mast of his dinghy broke on several trips. He often had to be towed back to the shore by a motorboat. Particularly grotesque: he couldn't swim, but refused to wear a lifejacket. "I'd rather drown like a gentleman."

Dinghy cruiser as a birthday present

In 1928, at the age of 49, he collapsed one day in Berlin. His family doctor, Dr János Plesch, diagnosed him with myocarditis. This condition can be life-threatening if you overexert yourself. Einstein, however, told the doctor faithfully that he often rowed his sailing yacht home when there was no breeze on the Havel lakes. Dr Plesch prescribed strict rest, a salt-free diet and a cure at a Baltic seaside resort. To his astonishment, however, Einstein recovered only slowly, even by the sea. Eventually the doctor was informed that he was also secretly sailing during his cure. Nevertheless, he eventually recovered. Probably not least because the psyche is also known to have a strong influence on the course of many illnesses - and Einstein just loved sailing so much.

For his 50th birthday, friends gave him his own dinghy cruiser: the "Tümmler", seven metres long and 2.35 metres wide, had a triangular Bermuda sail, a movable daggerboard and a cabin with two berths. Einstein affectionately called his mini-yacht the "little fat boat". It was a simple dinghy, just right for him. Einstein had no interest in regattas, speed records or technical bells and whistles. He turned down the offer of an outboard motor.

National Socialists confiscate the "porpoises"

Einstein idolised his old-fashioned "Tümmler". Just like his summer house in Caputh, a dreamy fishing village with around 3,000 inhabitants on the Havel lakes, six kilometres south of Potsdam, where he spent a lot of time from 1929 onwards. For Einstein, Caputh was simply "paradise". Here he found peace and quiet for sailing and for mental journeys into still little-explored realms of theoretical physics, such as aspects of paramagnetism and quantum physics, with which he did not like to make friends throughout his life, although he had also given the decisive basic idea for this.

What he particularly appreciated about his country estate was that "not every bleep becomes a trumpet solo". However, many people in the village were suspicious of the famous newcomer with the snow-white shaggy hair. When he stepped out of the forest in rough sandals and baggy tracksuit bottoms, a basket of mushrooms in his hand, some even reacted with fear.

Einstein was free on the water. When sailing, he could enjoy his "daydreams" and forget the world, he enthused in a letter. It helped him to relax completely. But his enjoyment of the trips with "Tümmler" was not to last long. Because the National Socialists seized power in Germany. On 12 June 1933, the dinghy was confiscated. On the same day, the "Vossische Zeitung" reported: "Professor Einstein's racing motorboat (...) was (...) seized for the Reich. Einstein is said to have intended to move the boat, which is worth RM 25,000, abroad." Yet the "Tümmler" only had a tiny auxiliary engine and its construction costs were only 1,500 Reichsmarks. At the time of the confiscation, Albert Einstein and his wife Elsa were no longer in Berlin, where Jews like them were facing increasing harassment.

Einstein does not shy away from rough sailing

When the Einsteins emigrated to New Jersey in the USA in autumn 1933, the physicist was able to fulfil a dream in exile: With a new boat of his own, the "Tinef", he sailed on the sea again - as he had once done in Kiel. The name of this small dinghy, only five metres long, comes from Yiddish and means "something worthless" - which Einstein certainly meant ironically. "While his hand holds the rudder, Einstein happily explains his latest scientific ideas to his friends present. He steers the boat with the skilfulness and fearlessness of a boy," enthuses his biographer and son-in-law Rudolf Kayser about the scientist's sailing skills.

However, the skill was, well, relative: sometimes the creator of the theory of relativity did not have everything perfectly under control on the water. In the summer of 1934, for example, while sailing with his friend Gustav Bucky in Rhode Island, he ran aground somewhere. But while his fellow sailor became nervous, Einstein just laughed and said nonchalantly: "Don't look so tragic, Bucky. You'll be waiting for me at home - my wife is used to it."

From 1937 to 1939, Einstein rented a holiday home in Nassau Point on the North Fork of Long Island in the summer and devoted himself to his passion for sailing on the Atlantic coast. It was there that he wrote a famous letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt, in which he warned of the danger of nuclear weapons in the hands of the National Socialists in Germany.

In 1939, he sailed daily on Long Island in the summer. "Einstein loved it when the sea was calm and quiet and he could sit in 'Tinef' and think or listen to the gentle waves that beat incessantly against the side of the boat," says biographer Jamie Sayen. But even rough seas did not stop the physicist from sailing - much to the chagrin of some of his companions.

Johanna Fantova, a librarian from Princeton who accompanied him on many voyages, writes in her memoirs that Einstein's skills as a sailor were not so bad. Rather, his immersion in thought was probably the cause of many a mishap. And: "Rarely have I seen him so cheerful and in such a good mood as in this strangely primitive little boat."

Last years

However, his recklessness when sailing was notorious. And also an almost adolescent delight in taking risks. Once, engrossed in a conversation, he almost rammed another boat. When his fellow sailor shouted "Watch out!" in shock, he casually swerved out of the way. "In his boat, as in physics, he sailed close to the wind," writes Einstein's British biographer Ronald W. Clark. In his mid-sixties, Einstein's bravado almost proved fatal in the summer of 1944: he was sailing in high seas on the Saranac Lakes in the US state of New York. When his boat hit a rock, it filled up and capsized. Under water, the physicist became entangled in a rope and was trapped between the deck and the sail. With his last ounce of strength, the non-swimmer managed to free himself. He was eventually rescued by a motorboat.

As a scientist in the USA, he endeavoured to find a kind of world formula that would link all physical phenomena. However, even the brilliant Albert Einstein failed at this Herculean task. But he had already found something more important: Serenity. It is quite possible that it was sailing that had taught him this attitude. "People are like the sea," he wrote in a letter in 1933, when he had to flee from the National Socialists, "sometimes smooth and friendly, sometimes stormy and treacherous - but mainly just water."

In old age, his weakened health no longer allowed him to sail. In the last few years, he hardly ever left Princeton. He often suffered from diffuse pain. Eventually, doctors diagnosed an enlargement of his aorta. On 18 April 1955, Albert Einstein died of internal bleeding at the age of 76. "I've done my bit," he is reported to have said, "it's time to go." Whether he was a Nobel Prize winner or a light sailor, he certainly knew that the sea would come for us one day. And the sea gives none of us back.