Dear readers,

Writing this text is incredibly difficult for me. I have been sailing as a cruising and charter skipper on the Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean and in some quite exotic areas for almost 30 years. The most beautiful moment for me is without question the AnchoringTurning into an as yet unknown, but previously carefully sought bay, the joy when it turns out to be as scenically beautiful as hoped. Turquoise water, perhaps, some greenery on land or a spectacular coastline with rocks. Anchor manoeuvre, engine off - peace and quiet. Swimming, snorkelling, lying in the sun. Then a dinghy tour to the unknown shore, perhaps looking for a restaurant for the evening. Otherwise a cosy cooking session with the crew in the evening. On days like these, a deep calm settles in my soul, a contented, happy feeling. My thoughts, which are often racing in my job and the daily grind, come to rest. The emptier the bay is, the stronger the effect.

But I'm afraid that's not too far off. And it could be the right thing to do. We're talking about anchor bans and, as an alternative, buoy fields. But please, let me explain.

My first cruise for YACHT in the nineties took me to the Turkey. At the anchorage, a fellow sailor jumped off the boat into the water, I stood on a rock for photos and took a picture at the time: he swam towards a huge school of fish with his hand outstretched, which elegantly parted around him and closed again after his passage. I still look at this slide every now and then.

Or about 20 years ago in the Sporades: As we sailed out of the Gulf of Volos in the Meltemi towards the island of Skiathos, we were accompanied by flying fish taking off from the crests of the waves. Whole shoals, hundreds of them, glisten in the backlight, race briefly across the water and then dive back in. Deeply moving moments that I have never forgotten, you feel at one with nature in such situations.

Or Croatia: Sitting on the pier in the late evening light, a shadow flits over the rocks very close to the shore. The visitors stand up from their seats and look: An octopus, as big as an open umbrella, runs over the rocks with its tentacles as if on feet in search of prey.

You can guess what's coming. It's been a long time since I've dived through dense schools of fish in the Mediterranean. I see flying fish less and less and only occasionally. Octopuses from time to time, but never such large specimens. At the same time, a small census: in September 2022, I anchored in the bay of Lakka in the Ionian Sea. There were 54 yachts in the bay, it seemed incredibly crowded to me. When I spoke to a tavern owner about it, he laughed and told me that there were up to 100 yachts in the high season. I searched my archives and found an old slide from a trip just over 20 years ago - also in September. There were about a dozen boats in the bay. If you dive there today, you see: Sand. Sand. Sand. Raked by thousands of anchors every year. The sandy bottom may glow a beautiful turquoise colour in the sun, but ecologically it is a desert.

A friend of mine has been a cabin charter skipper for over three decades on the Adriatic Sea. And he is a professional diver. He reported 10 to 15 years ago that it was a tragedy how the bottom in the bays was becoming deserted and, even worse, partly littered. Want an example? In the Kornati islands, I met a biologist and apnoea diver who sails her old wooden gajeta for long periods in Croatia every autumn. Her family home is close to the bay of Kravljacica. Every time she is there, she dives up the rubbish from the bottom. When I was there, she brought up six huge bags of rubbish from the bottom.

A few weeks ago, like a thunderclap, a thunderbolt struck into this dull, smouldering feeling The news arrives that the ecologically valuable, huge nature reserve of the Maddalenas on the north-east side of Sardinia will no longer be open for overnight anchoring. All boats must leave in the evening, only buoys and piers may still be used for overnight stays.

In Croatia, buoy fields have been springing up like mushrooms for years. And the price rally there is frightening: there are already buoy fields whose operators charge five euros per metre of boat. And they don't even guarantee a reasonable technical standard for the basic weights. They are close together, the bays are full to bursting and it feels, there's no other way to put it: like a boat car park.

But I fear that yacht tourism has exploded over the last few decades and the damage we are causing is immense. But does this mean the end of free anchoring is slowly approaching? Will we - rightly - soon only be moored at buoys?

Let me give you some encouragement. A few years ago I sailed in the Caribbean in the BVI. A huge number of bays there now have paid buoys, some of which have been in place for over a decade. In Trellis Bay, I met the musician and diver Michael "Beans" Gardner, who has been sailing and diving in the Caribbean for three decades and finances his life as a musician in hotel resorts. And he enthusiastically told a completely different story. For years, the ground beneath the buoy fields has been overgrown with seaweed. The turtles are there in much greater numbers because they graze the seagrass meadows like cows. Crabs and small fish have returned, as have snails. In many places, life is gradually returning to the bottom after years of being a sandy wasteland dotted with rubbish from anchored yachts. Beans was very pleased. The hoteliers, on the other hand, were not always. They said that some guests were disappointed when the shimmering turquoise water no longer shone in front of the golden-yellow palm beaches. This is because the seagrass bed is dark green. If you've grown up with dead ground, you just don't know any different. One of the most dangerous phenomena of nature conservation: a generation is growing up that has never experienced intact nature in many areas and therefore cannot miss it.

The enormous effect of protected areas has long been recognised by biologists. Strict protection simply works. Full stop. Example Caprera before Majorca. The bay, which has been marked with buoys for decades, is one of the most ecologically valuable areas in the Balearic Islands. Diving there is almost frightening, as you are surrounded by shoals of astonishingly large fish. And an astonishing number of species. MPA's in loose succession is the magic word for reversing the slow decline, according to the conservationists' credo. Marine Protected Areas, is the translation. Protected areas, lined up like a string of pearls, strictly regulated, with anchoring bans and buoy fields at intervals of 20 or 30 nautical miles. In this way, a corridor of life could be drawn through the entire Mediterranean, which would bring about a reversal of the slow decline. And by the way: anchoring in seagrass beds has been prohibited by EU law for many years anyway. It's just that hardly anyone cares. There are tentative attempts to implement such a plan for the Mediterranean, but only in the long term.

So what can the future of ecologically sound cruising look like? Does free anchoring really have to disappear? I don't think so. The following would be logical: The countries bordering the sea join forces and place the ecologically valuable zones at reasonable distances from each other under strict protection. At the same time, there is an initiative to lay out many more buoys, because there are simply too few of them. The fields come under state control, are well maintained and are not given to windy tenants who want to maximise their profits, as is so often the case in the Mediterranean. The prices are based on the cost of maintaining the fields, not on how much money the income might be able to plug in some other budget. Snorkelling trails run by volunteers (e.g. in France, Denmark), guided dives, information centres are mandatory so that people understand why their rights are being restricted and accept the rules.

And at the same time, ecologically less important areas directly adjacent to it are still available for anchoring. So you can experience the difference with your own eyes in the smallest of spaces. Because the mistake of nature conservation in so many places is to want to exclude people completely, to "leave nature to its own devices". This only leads to frustration among those who are excluded and there is no realisation of the value of the measures.

Let's just make this the task of our generation, which has destroyed many bays. Once the corridor of life has been created, our children can then decide whether they want to continue "reforesting" under water or not.

As I said, I found it difficult to write this text, as the implementation of such measures would also mean many restrictions for me. But if I could still experience the slow recovery of old, cherished anchorages, that would be a prospect for my old age that I would really like.

Andreas Fritsch

YACHT editor

Click on it to see through:

The week in pictures

Recommended reading from the editorial team

Beneteau First 36 SE

A touring regatta boat in top form put to the test

Beneteau and manufacturer Seascape have significantly slimmed down and rebuilt their already powerful First 36. A short test of the new SE sports version.

Hanse 360

Sailing space miracle with an independent touch in the test

Space, potential, exciting lines, plenty of options. How Hanse's smallest model aims to redefine the standard in the eleven-metre class.

Ghost ship

Atlantic rowing boat resurfaces after three years

A ghost ship, which turned out to be an offshore rowing boat that was wrecked three years ago, was salvaged off the French Atlantic coast.

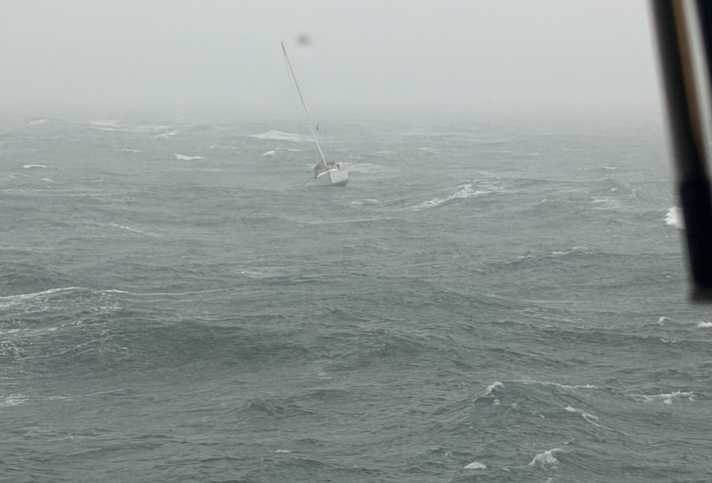

In distress

Dramatic rescue of a single-handed sailor in a winter storm off Heligoland

A Norwegian skipper was rescued from distress at sea west of Heligoland following engine problems and a damaged mast. Despite a storm of nine Beaufort and waves up to five metres high, the crew of the rescue cruiser "Hermann Marwede" was able to track him down. He was eventually rescued by a naval helicopter.

Dufour 48

Cruising boat with edges and plenty of space on test

With the Dufour 48, the shipyard is launching another cruising yacht with an independent design. The focus is on volume and comfort, just like the competition.

Sun Odyssey 455

New design for a proven concept

No break in the Jeanneau development department. The new model in the Sun Odyssey touring range, the new 455, is now being presented with many exciting new features.

Jules Verne Trophy

Eight proud women - Cape Horn has never been passed like this before

A proud achievement for the eight women on "Idec Sport": The Famous Project was the first all-female crew on a maxi trimaran to pass Cape Horn.

J/36

Guaranteed success in a new edition

J/Boats and manufacturer J Composites in France have remodelled the successful J/112E and are now launching the boat on the market under the name J/36. The main change is the layout in the cockpit.

In distress in the Atlantic

Sailing yacht crew rescues rower off Cape Verde

Emergency at sea off the Cape Verde Islands: The crew of the sailing yacht "Raven" rescues an English Atlantic rower and tows her 200 nautical miles to the Cape Verde Islands.

Oceantec 43

Judel/Vrolijk launch new performance cruiser with swivelling keel

At Oceantec, a powerful cruising boat with a canting keel is built in small series according to a design by the Dehler designers Judel/Vrolijk & Co.

Newsletter: YACHT-Woche

Der Yacht Newsletter fasst die wichtigsten Themen der Woche zusammen, alle Top-Themen kompakt und direkt in deiner Mail-Box. Einfach anmelden: