- Gustaf was like that: thorough and meticulous

- Motor must be installed in "Sindbad

- The guy hadn't even measured anything

- The sickening crack of splintering mahogany wood

- Gustaf didn't think much of the "thumb measure"

- The drilling vandals

- That was worth a "Skol"!

- His ship had won

- Author Wolfgang J. Krauss (1915-1986)

Text by Wolfgang J. Krauss

Millions of intelligent treatises, dissertations and similar pearls of wisdom fill the archives of universities and libraries. However, the significance of the thumb in people's lives has never been analysed. Yet it is precisely this question that deserves to be analysed in depth, because it is here that physical, sociological and emotional functions influence the fate of mankind in intimate harmony.

Also interesting:

Take Gustaf, for example. How many thousands of working hours did he waste in the course of his life verifying scientifically proven facts? Yes, to what extent has he diminished the national product through such pedantry and thereby harmed the entire nation? Gustaf knows nothing about the "importance of the thumb in the life of nations". In other words, he knew nothing. This has changed, and in the following way: Gustaf, like all notorious sailors, was a pedant of considerable proportions - a yardstick made flesh, so to speak. When Gustaf wanted to drill a hole, he didn't just grab a six-millimetre drill bit from the back box and drill away. No, first the thickness of the drill was measured with the vernier and compared with the number stamped on it. Only then did the drilling begin.

Gustaf was like that: thorough and meticulous

The folding rule and calliper were his best friends and he always carried them with him. There was always something to measure! He didn't mind getting on the nerves of those around him - he felt like a misunderstood preacher in the desert and felt sorry for anyone who wasn't so accurate. Well, you know how it is with sailors: everything has to be done "this way" and no other, the sheets are put on "this way", the rigging is put on "this way", halyards are shot up "this way", nuts are tightened "this way" and sails are set "this way".

Whenever Gustaf wanted to change some insignificant detail on his ship, his face would show agonised, brooding features weeks in advance. He entered mysterious numbers in his notebook several times a day. His office work suffered from the intense pressure of having to sketch private construction drawings on many small pieces of paper. And the problem of connecting two pieces of pipe with a flange could even keep him awake at night.

It was the same with insignificant things. But what fanatical meticulousness Gustaf showed when it came to really big things! Once, in order to move a leading eyelet on deck, he made seventeen sail plans - with various angles of inclination of the mast, foremasts set forwards and backwards, foresails struck high and low with single and double-sheeted sheets. He then built a 1:20 model with real sails to which silk threads were attached in order to control the jet stream of the overlapping cloth using a hair dryer. In the end, everything was left as it was because he didn't feel that the displacement of the leading eye was ready for construction.

Yes, that was Gustaf! Thorough, meticulously precise and imbued with an immense thirst for research.

Motor must be installed in "Sindbad

That was probably the real reason why he had refrained from installing an engine in his old "Sindbad" for so long. There was too much to think about! It wasn't just the selection of a suitable engine type that gave him such a headache. No, the mere thought of the technical feasibility of the problem could make him startle in bed at night, causing Frieda to ask anxiously whether he had a fever. And all he could think of was how he could lay his stern tube without damaging the numerous long threaded bolts that a clever yacht designer had provided at this point more than thirty years ago.

In the end, it was only thanks to Frieda's persuasive powers that he took the bold - and for him downright violent - decision to have an auxiliary engine installed by a small Danish engine factory. The captain's wife was fed up with the eternal brooding and finally wanted to see a beaming captain again.

The weeks before were terrible! Several times they threatened to divide Gustaf and his loved ones for good. He no longer had any time at all for his job, and even at night he measured the frame angles and engine slopes in his mind, mentally raised the cockpit floor and lowered the cabin floor, drilled holes through the wings and outer skin (what a horrible thought!) and made complicated drawings and circuit diagrams for all the fiddling around that is involved with such a smelly and noisy piece of equipment. His notebook was filled to the brim with numerical acrobatics and his brain resembled a pressurised boiler with a jammed safety valve.

The guy hadn't even measured anything

They arrived in Denmark in this condition. "Sindbad" went into the shipyard and a young man in blue overalls climbed aboard. Gustaf unpacked his notes and set about emptying his brain. At last the pressure was off him. But the young technician just shook his head. He didn't want to see the notes or hear Gustaf's explanations in bumpy Danish. He only looked under the floorboards once, scratched his chin, put his head to one side and walked away again. That hadn't been much to begin with. The guy hadn't even measured anything. Surely that was just the vanguard and the actual measuring team was still to come.

The young man came back in the afternoon. He had brought a colleague with him. They both sat in the cockpit and stared at the floor. Every now and then they growled a word to each other. They paid no attention to Gustaf and his notes. Then they both stood up.

"Okay," said the blue one, "assembly starts tomorrow."

Gustaf thought he couldn't hear properly. Assembly? They must have been crazy! Where were the installation drawings and the assembly plan? That was an engineer's job! And it had to be measured beforehand. Bloody hell!

"Har di keenen Inschenier?" he asked the blue man angrily.

"Yes," he replied, "I'm an Inschenian myself."

"What about the drawing? - Tekning?"

"Nix Tekning - everything is okay!"

It was another bad night for Gustaf. Only when Frieda became energetic and even the unsuspecting Julchen added her two cents did Gustaf close his eyes and switch off the light. What was this going to be like! His beautiful ship! And not even a drawing. That's what happens when you have something like this done abroad!

The sickening crack of splintering mahogany wood

In the morning, a column of friendly men arrived, carrying a green-painted engine block on a handcart. They went "hoh-ruck" and before Gustaf knew it, the iron block was in the cockpit. The blue man narrowed his eyes, stuck a wedge under the flywheel and lifted the engine by the front end. Then he took a hammer and, with quick, practised blows, knocked apart the panelling of the side scuttles, removed the dents and floorboards and called for a saw.

Gustaf's stomach rose sourly. Before he could turn away with tears in his eyes, he saw one of the guys using a saw to cut a huge hole in the bridge bulkhead, big enough to push three engines into. When he went to collect his construction notes spread out on the bridge deck, he had to search for them for a long time. The blue one had sat on it. A blade was stuck under the sole of the man's shoe with the saw.

The assembly had begun. Gustaf got out. He realised that he was superfluous and preferred to watch the rest of the work from a ladder leaning against "Sindbad". But the sickening cracking of the splintering mahogany wood and the nerve-wracking sound of the saw soon drove him away. Accompanied by Frieda and Julchen, he turned his steps out of town. It was a silent march.

Around midday, his restlessness drove him back to the shipyard. Next to "Sindbad" was a mountain of varnished timbers that made it easy to recognise where they came from. Gustaf had lovingly sanded and polished them every spring for years. And how often had he said to Julchen while sailing: "Get the sand off your shoes - think of the varnish!" Now the wreckage lay before him. Did everything have to be ruined because of such a stupid engine? No, he wasn't up to it. It was too much for him.

Gustaf didn't think much of the "thumb measure"

As the "Blue Gang" ruled on deck, he squatted resignedly on a pile of planks in the shadow of the "Sindbad" and gave in to his despair. A fat ship's carpenter was in the process of knocking out the threaded bolts embedded in the deadwood of the sternpost with a heavy sledgehammer. Hey, how that cracked! With every blow, "Sindbad" shook in her frames and you could see the bracing moving. The support timbers would probably fall over next, but that was fine with the blokes. Why did they treat the ship so roughly?

After work, Gustaf, Frieda and Julchen climbed back on board. My goodness, what a mess the ship looked like! There were tools lying around everywhere and wood scraps and sawdust piled up in every corner. The engine was cowering on the floorboards like a vicious predator. Gustaf covered it with a piece of canvas. He could no longer see the beast.

The carpenters arrived very early the next morning. Frieda quickly cleared away the breakfast dishes and Gustaf disappeared from the ship, growling. The men had brought along oak beams as thick as their arms, which they worked with axes to fit the ship's belly. Aha, these were to be the foundations!

Gustaf didn't think much of the "sense of proportion". But what was happening here was no longer a sense of proportion - it was a "measure of the thumb" with criminal recklessness. However, the men didn't let Gustaf's hostile looks bother them in any way. They adjusted the sides of the foundation, took away a little here with the axe, rasped a little there, checked the imprint on the ship's side with red lead and crowned their work by driving tension-length zinc nails - which they called "spikers" - from the outside through the hull into the creaky oak wood of the foundation. Gustaf's whole body trembled. He didn't think there could be anything more barbaric than nailing his magnificent hull with the finger-thick spikes. But that was only the beginning.

The drilling vandals

Suddenly, a man with a two-metre-long drill stood at the stern of the pointed gaff. Where the deep-going rudder blade normally turned in its pivots - two handbreadths below the waterline - he placed the tip of the drill and began to turn the device with swift, powerful movements. He obviously wanted to drill the hole for the stern tube.

"Stop," shouted Gustaf, "stop, stop!" And he was already standing next to the drilling vandal and asking five things at once. Why exactly there - who had measured it - where he had the drawing - whether the shaft pitch had been taken into account and how he knew whether he was coming out in the right place with the drill.

The man didn't understand what Gustaf had asked him in German, but he nodded his head good-naturedly: "Jo, jo." He knew people like Gustaf, who always want to have everything mathematically calculated that an old boat builder has in his fingertips. He raised the thumb of his right hand up to eye level and aimed it at an imaginary point in space - the international symbol for over-the-thumb aiming. He gave Gustaf a soothing grin, as if to say: "Don't worry, mien Jung, we can deal with something like this every day."

And then he continued to drill carefully. With every turn of the hand spade at the end of the drill, the monster creaked its way into the dead wood. Centimetre by centimetre, decimetre by decimetre, half a metre, one metre, one and a half metres and finally two metres. No one was there to shout to the carpenter: "A little higher, a little lower, now a little to the left - that's right." He just stood wide-legged on the bumpy floor behind the "Sindbad" and turned his steel freehand into the bowels of the ship without looking closely.

That was worth a "Skol"!

Where do you think Gustaf was? After half an hour of nervously jumping from one leg to the other and jumping around the drilling man like a dancing dervish, he could no longer stand it on land. He climbed on deck and stared spellbound into the bilge, where the engineer had made a cross with chalk at a certain point on the keel beam. This was where the tip of the drill was supposed to emerge. It was hard to believe that such a miracle was possible! Gustaf's pupils clung to the chalk cross like a cat's eyes to a mouse hole. He didn't believe in miracles, indeed, he almost wished that the drill had come to light in the wrong place. Then he would have been right with his thoroughness.

When he had fixed his gaze on the cross for a long time without anything happening apart from the crunching sound of the grinding drill, Gustaf became afraid. Perhaps the tip of the drill did not emerge at all and continued to turn horizontally in the dead wood until the end of the world? Or maybe it came out sideways or even broke off? Gustaf's forehead was covered in cold sweat. He looked down over the railing at the carpenter, but he was puffing boredly on his pipe and turning his wooden handle with the regularity of a fan.

By midday, Gustaf's legs had fallen asleep and the backs of his knees were aching. As he struggled to fight his nervousness with his tenth cigarette, it seemed as if the white cross was moving slightly. There was a tiny gap in the keel, dividing the cross into two equal halves as if it had been circled. One chip vibrated, the cross gaped apart. The tip of the drill bit appeared in its centre.

Gustaf was gobsmacked. He grabbed the rum pack from the bottle cabinet and climbed down to the carpenter. That was worth a "Skol"! But as a convinced pragmatist, he had to find out how something like this was possible: drilling a two-metre deep hole through a keel that was only a hand's width wide and landing exactly where he wanted without a folding rule, a drawing or an angle gauge! The man with the drill laughed sheepishly. He raised his thumb again and took aim at the sun.

His ship had won

There is not much more to report on the subsequent events. The engine was fitted, a beautiful new wooden panelling was built around it, a teak box was made for the reversing gear and a flashing dashboard was screwed into the cockpit. Nothing was measured at all. Just looked, built and fitted - and there was another new box sitting somewhere.

When everything was ready after five days and "Sindbad" rolled back into the water, Gustaf had to honestly admit to himself that his ship had won. After the engine also ran straight away - something Gustaf had doubted until the very end - there was really nothing more he could have criticised.

The next morning, "Sindbad" left the shipyard to continue the interrupted holiday trip. The dockers stood on the shore and waved - the blue man in his overalls, the bull with the sledgehammer and the drill worm without nerves.

Gustaf looked at his thumb. A beautiful, strong thumb. A German thumb - practical, sober and used to giving orders.

As he wanted to enter the Belt, he reached for the nautical chart and the course ruler to plot his course. But after a moment's thought, he threw both back into the cabin and took a rough bearing north-north-west with his left thumb. Then he tightened the sheet and set course. Without a ruler.

He looked at his thumb again. It's actually a great thing, a thumb like that. And not even a German invention.

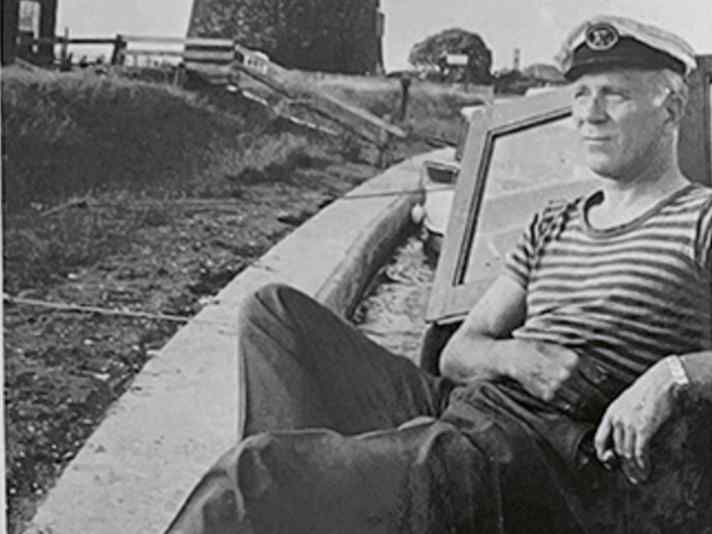

Author Wolfgang J. Krauss (1915-1986)

The son of the director of a nautical school, he grew up in Stettin and sailed there from the age of seven. He took part in the Bermuda Race and the Transatlantic Race in 1936 and the Fastnet in 1937. After the war, he owned various pointed-rigged boats named "Wassermann", which he sailed in the company of his wife and son. However, he always said of himself that he was no Gustaf. The favourite theme of his literary work: the magical attraction of the sea to us humans and our difficulties in coming to terms with it. The following books have been published by Delius Klasing Verlag: "Die Sonderbare Welt des Seglers Gustaf", "Freud und Leid des Seglers Gustaf", "Neue Geschichten vom Segler Gustaf", "Szenen aus dem Seglerleben", "Und Schiller war doch ein Segler", "Von Seglern und Menschen", "Segler Gustafs heile Welt". These and other sailing books by Krauss are still available in antiquarian bookshops today.

The article first appeared in YACHT Classic 2/2024.