First anniversary of his death: "... and they didn't believe a single word" - Wilfried Erdmann's first circumnavigation with the "Kathena"

YACHT-Redaktion

· 08.05.2024

from Uwe Janßen

A badly battered vehicle arrives in Heligoland in the last light of 7 May 1968. At the helm of the 7.60 metre short boat is a young man, 27 years old, all alone, more dead than alive. He has travelled over 8,000 miles in a row in a gruelling 131 days. No one before him had been alone at sea for so long. For more than two days, he sat at the tiller without interruption, eating coffee grounds to revitalise himself, hunger and exhaustion making him hallucinate about cake and milk. But agony is not the worst thing. He can live with that.

The harbour master asks where from. Last harbour? "Cape Town." The perplexed gentleman has just taken up his duties and compassionately leaves the emaciated bearded figure his sandwich. So unspectacularly ends what is in truth a sensation: Wilfried Erdmann has sailed round the world single-handed. No German had ever done it before, no one had ever dared.

Nobody believed Wilfried Erdmann

In fact, only four of his compatriots have ever achieved this with Crew. Erdmann became a hero on this day, with all due caution when using the word. Nothing less. But - and this is worse than any drudgery - Germany receives him as a weirdo, as a kind of Felix Krull at sea. His welcome after 20 months at sea consisted of a wall of mistrust. They didn't believe him. Not a word.

How eagerly he looked forward to returning home! Until he arrives home. An emissary from the German Sailing Association tells the reporters that it is "almost a lie" to say that it is possible to sail around the world with such a small boat. Erdmann would like to turn back on the spot, far away, back to the sea, to his beloved solitude.

Today, sailors are travelling the world in droves. They have fine, fast yachts, a sumptuous selection in the on-board bar, they wear warm, waterproof, breathable high-tech clothing, a machine desalinates the seawater, they chat via satellite mobile phone from anywhere in the world, and the GPS reveals their position to the nearest decimal point. 1968 seems like the Stone Age of sailing in comparison. Under archaic conditions, with a tiny boat "neither designed nor built for such a journey", once around the world, across all the oceans, through storms and doldrums - at the time, that really only deserved one attribute: incredible.

Video: Wilfried Erdmann reports on his first circumnavigation of the globe

An adventure beyond imagination

This adventure is beyond imagination. "Nobody had any idea when I would arrive, there was no communication. So I arrived and said: 'Here I am'. I was happy, but not for long. The next day, the newspaper said: 'He didn't do it at all!"

Shortly before, Francis Chichester had achieved something similar. The end of his single-handed circumnavigation was like a triumphal procession, with 400,000 enthusiasts cheering him on in England. Erdmann, on the other hand: "No press, no family, no friends at the reception. It was just me, that wasn't the worst thing." In general, Germany reacted far less euphorically. Customs put his "Kathena" on a chain. He was told to pay 200 Deutschmarks import tax for the ship, or 320 euros at today's value. He doesn't have that much.

It was just me, that wasn't the worst thing."

Erdmann, born in the Pomeranian town of Scharnikau in 1940, came from a modest background. "I only knew what hunger was, but not what sailing was." The family fled to the GDR and settled in Karstädt in Mecklenburg. Erdmann completes an apprenticeship as a carpenter. Wanderlust takes hold of him. At 17, he visits an aunt on the other side of the zone border, in Büchen. He has no intention of ever returning to his parental home. He only stays in Büchen until he receives West German papers. The passport is his ticket to the world; now, at last, it is open to him.

He earned 1,000 Deutschmarks a month as a carpenter. But he, whose only connection to the water to date was his neighbourhood carp ponds, wanted to go to sea at all costs, money was of secondary importance. He hired himself out as a young man on a commercial ship for just 200 marks a month.

Erdmann comes across the "Kathena" during a visit to the pub

Sailing boats fascinate and disturb him in equal measure. He has no idea whatsoever about sailing. And no idea how he could learn - some things were just like they are today 40 years ago. "When I saw in the brochures what an hour's lesson at sailing school cost and how many hours you needed to finally be able to set off on your own for the first time on an afternoon trip in Sunday weather, I felt sorry for my hard-earned money."

On 2 November 1965, the "have-not" (Erdmann) makes a momentous bar acquaintance in Alicante, Spain. At the bar of a bodega, he struck up a conversation with a gentleman "around 60, with white hair, pipe and moustache, easily recognisable as English". Erdmann tells him about his longings. "Are you looking for a boat?" asks Mr Nuttall. "Yes, but I can't afford one."

Nuttall offers him an acceptable price for his 14-year-old ship, 8600 marks. However, the lady is in a pitiful condition, she is, according to Erdmann, "dismal to look at. Chipped paint everywhere, flaking rust, loose shrouds, rotten ropes, cracks in the planks." The new owner is unable to judge her sailing characteristics: "I knew nothing about sailing." So he decided not to test sail her. At the very least, it would have told him that the boat was faulty.

First entry in the logbook: "How happy I am!"

Erdmann sacrifices half of his savings for the "Kathena" and spends money twice more that day. Firstly, he settles his hotel bill - he has no idea that the previous night was the last time he will spend in a fixed bed for years. And he buys a logbook, an ordinary cash book. In the years that followed, his travel notes would move, impress and enchant the sailing world - the distillations in book form sold like hot cakes, with his later publishing house Delius Klasing alone supplying fans with hundreds of thousands of copies. On that day, Erdmann writes the first of thousands and thousands of sentences in a logbook: "How happy I am!"

Happy? With this boat? "The cabin was no longer than the bunk, and it was just long enough for me to lie in." It hardly looks any better vertically, standing height my arse: movement below deck is only possible when bent over. "I could always feel the edge of the table in the pit of my stomach." No locker, no cupboard on board, "there wouldn't even have been room for one." Erdmann lives out of his duffel bag for years. In many ways, it is a journey into the unknown. Erdmann doesn't know when he will ever earn money again, he doesn't waste a thought on financial security.

Wilfried Erdmann's first trip turns into a disaster

In Alicante, he met other sailors, a small, manageable, close-knit group. Among them was Bernard Moitessier, the great Frenchman who would achieve world fame a few years later when he abandoned the first single-handed world regatta, the Golden Globe, while in the lead and disappeared into the South Seas. In the Stone Age of sailing, names such as Moitessier, Robin Knox-Johnston or Bobby Schenk played no role at all. There were no series-produced boats worth mentioning, nor institutions such as the blue-water self-help organisation Trans-Ocean. And the possibilities for communication - essential for the preparation and realisation of every cruise - are mainly limited to writing letters addressed to the supposedly nearest port.

Erdmann slowly got to grips with the subject, learned "the basics of navigation in theory" from Moitessier, familiarised himself with the boat on short trips and set off on his first sea voyage on 13 May 1966. 20 miles to Benidorm "seemed an insanely long way". The trip began with a collision with the quay wall and ended with the jib torn to shreds on the pier of the destination harbour. A disastrous first, but Erdmann learns his lesson: "I realised that I was far too inexperienced and demanded double discipline."

He has to leave before it's too late

Erdmann prepares his ship. Among other things, he needs bilge pipes for the cockpit and a sea fence. He procures gas pipes and bends a railing out of them by hand. For almost a year, he says, he "bummed around" in southern Spain in this way, until he realised from the fate of other long-distance aspirants that the same could happen to him: Planning, wishing, dreaming - and yet never getting away. He has to leave before it's too late. In fact, at that moment he had "not set his sights on sailing around the world, but merely on leaving the lazy life in Alicante". He set sail on the morning of 25 July 1966. This date marks the beginning of Erdmann's great career.

Unfortunately, as we understood it at the time, all this had nothing to do with sailing. Sailing was the preserve of the elite, in "isolated clubs", as Erdmann put it. A colourful bird like him, almost penniless, would never have found the necessary guarantors for admission to this illustrious circle, even if he had wanted to. Not just because of his status - at the time, the clubs attached great importance to the fulfilment of criteria, none of which he met: competence and qualifications, above all meticulous trip planning, safe navigation and good seamanship.

Erdmann calls himself a "greenhorn at sea"

Expertise? Close to zero. Erdmann calls himself a "greenhorn at sea". Qualifications? He doesn't have a sailing licence, hardly any experience. He only realises "the enormity" of his journey when the time to turn back has passed.

"Looking back, of course, it was reckless, but I was young, and young people don't always realise exactly what danger means. The lack of sleep, the boat traffic, heavy weather. I approached it relatively carefree. A bit naive. And in the end, someone arrived who still managed it without any damage. That didn't necessarily make me popular with the clubs." Their problem: it's not one of them, not an established person who becomes a sailing pioneer, but a nobody. Unbelievable.

I approached it relatively carefree. A bit naive."

Erdmann somehow navigates his way around the globe, sometimes sketching out the nautical charts he needs. His watch goes on strike after an involuntary swim in the harbour of Alicante, the radio that still gives him a time signal ("I have to anticipate when the last 'beep' will sound") is destroyed by a boarding party in the saloon. And then the sextant is also broken. Erdmann notes: "Since the clock and radio broke and I no longer have an exact time, I've been keeping a close eye on the arc of the sun so that I can measure the angle with the sextant at the time of its peak and then calculate the latitude. But one day I'm too careless with the expensive device and the basic setting on the calibrated precision instrument shifts. Disc paste! I've long since been using my thumb to calculate longitude. In future, I won't be able to calculate the latitude accurately either. So now I really am travelling across the Atlantic like Columbus."

2879 miles flying blind across the Atlantic

Erdmann orientated himself solely by compass, stars, sailing instructions and current descriptions. He missed Barbados, but arrived in Kingstown, the capital of the Caribbean island of St Vincent, on 12 December 1966. After 47 days at sea. After 2879 miles, almost flying blind. Unbelievable. The Italian Captain's Association later awarded him the title of "Bravest Sailor of the Year".

In Germany, it only slowly becomes clear what Zausel, who has arrived in Heligoland, has achieved. One check after another confirms his statements. "They checked," says Erdmann, "you wouldn't believe it!" He is initially surprised when biologists scrape growth from his underwater ship. It is sent to the laboratory for analysis. An expert has to certify the authenticity of his logbooks. A single-handed sailor rarely has witnesses. Only the confirmation of two ship encounters and the inspection of mail from all over the world that he had sent to his girlfriend Astrid von Heister dispelled any doubts.

From now on, the mood changes. What has this guy done!

Matches keep the "Kathena" sealed

What a fight he put up! The "Kathena" is constantly taking on water, and Erdmann spends a good part of the journey pumping out the bilge. His calfing remains ineffective because tropical worms bore through the mahogany. Small fountains gush out of the approximately three millimetre thick channels. In the middle of the Pacific. Erdmann spikes the boat with matches and sails on for weeks without any problems.

He starves himself to Tahiti. For some unknown reason, the gas cylinder runs out early on in the voyage. Noodles and rice are now useless as provisions, which means no hot food for 43 days, almost a month and a half, and instead raw onions, "cold tinned beans and dried fruit. If only I could at least have a hot cup of coffee." He reached Tahiti on 5 April 1967.

Erdmann is constantly sailing on the edge of bankruptcy. Unlike Chichester, his adventure is by no means fully financed. The ship urgently needs to be refloated, 52 dollars, too expensive. In Panama, a demurrage charge of 2.50 dollars is demanded "just so sinfully much!" Time and again, he has to take on jobs on his stopovers, which at least earn him something, enough for the next stage.

He sets "records in slow sailing" in calm conditions, no engine to push him, he has removed the propeller after the defect, it only slows him down. Gruelling days. And nights. In the Caribbean, he had to board the masthead in a storm to replace the broken halyard. A madness on the dancing ship in complete darkness, "the slightest weakness means the end". He doesn't know how, but he manages it, arrives in the saloon completely shattered and realises that the water in the ship is up to the floorboards. He bails until he is exhausted. Lakes get in, the water runs "in buckets into the collar of the oilskins and out of the boots again". Erdmann reaches Cristobal on 4 January 1967.

The media machine starts up

Apart from his new girlfriend and future wife Astrid, he has not let anyone in on the plan, not even his relatives in Büchen, and certainly not the media. When Bild reporters got wind of Erdmann's arrival on Heligoland, they instinctively sensed the story. While he despairs at the doubters, the professionals immediately realise that this discussion will give them headlines for days. From then on, Erdmann is the headline topic. He pleads in vain: "Don't make such a fuss." The media machine starts up.

He sails from Heligoland to Cuxhaven, where the old floating jetties can barely bear the weight of the 90 curious travellers. A reporter from "Stern" comes on board and takes him to the Hamburg headquarters, where editor-in-chief Henri Nannen himself buys the story exclusively from him. Erdmann is moved when he is handed 12,000 Deutschmarks in cash. That is more than half of his total travelling expenses - including the ship - of 21,000 marks. More than the rest of his expenses came from further fees and the sale of his "Kathena".

Now he's probably someone. But the sudden "sea hero" ("Süddeutsche Zeitung") is not duly celebrated everywhere. Erdmann was denied the Schlimbach Prize, awarded for "the best German ocean sailing achievement of the year". Bremen jury member Rolf Schmidt explains the reasons: "Firstly, he was neither before nor after in a club, secondly, he had no patent, thirdly, he had no preparation in our sense." Unbelievable.

Chichester is ennobled, Erdmann gets ten kilos of Mettwurst sausage

Francis Chichester had completed his single-handed circumnavigation the year before in the "Gipsy Moth IV", which was more than twice the size, with almost four times the sail area, complete equipment including a working engine and 24 times the budget. England honoured him like a saint: A title of nobility, a knighthood, an honorary state pension and the Order of the British Empire.

The adoration of the "German Chichester" ("Bild"), on the other hand, remains within narrow limits despite his media presence in print and television. Stern" smugly lists the gifts Wilfried Erdmann has received as the local equivalent of nobility and a lifelong income: "1 book from the chief municipal inspector of Helgoland; 1 armchair from Möbel-Lemke, Büchen; 1 watch from the municipality of Büchen; 1000 DM donation from Maschinenfabrik Tuchenhagen, Büchen; gold-plated celebrity medal from the TV programme 'Goldener Schuss'; 10-kilo pork sausage from the town of Schwarzenbek." It seems that not much has changed in principle over the past 40 years.

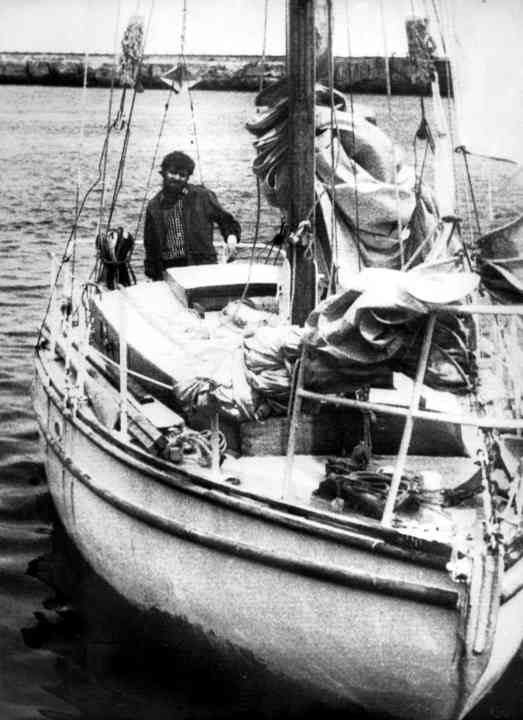

The original "Kathena"

Erdmann's first ever boat was built in 1952 by John A. Ley in Scarborough, England. It was 7.62 metres long and 2.32 metres wide. The centreboard went 0.90 or 1.50 metres deep, displaced 4 tonnes and carried 24 square metres of sail on the wind. The water tank had a capacity of 60 litres and collecting rainwater was part of everyday life on board. Erdmann paid 8,600 Deutschmarks for the yacht and sold it to a Hamburg shipbuilding engineer in 1969 with a mark-up of 500 Deutschmarks. In the meantime, he had invested around 5000 marks in equipment.

Wilfried Erdmann's first journey

(10. 9. 1966-7. 5. 1968)

- Alicante-Las Palmas, 17 days, 768 nautical miles

- Las Palmas-Kingstown/St. Vincent, 47 days, 2879 nautical miles

- Kingstown-Cristobal/Panama, 13 days, 1173 nautical miles

- Cristobal-Balboa/Panama (canal cruise), 1 day, 46 miles

- Balboa-Tahiti, 69 days, 4792 nautical miles

- Tahiti-Port Moresby/Papua New Guinea, 46 days, 4004 nautical miles

- Port Moresby-Cape Town/South Africa, 98 days, 8026 nautical miles

- Cape Town-Helgoland, 131 days, 8062 nautical miles

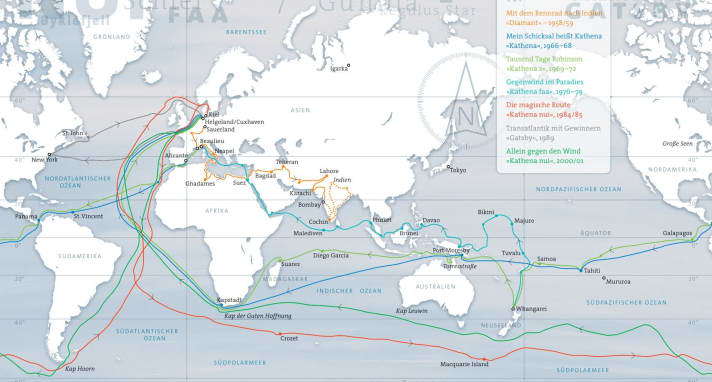

The most important trips of Wilfried Erdmann

Just a year and a half after his arrival, Erdmann sailed around the world again (1969-1972), this time with his wife Astrid. In 1979, the two of them embarked on a long voyage to the South Seas with their son, who was initially three years old. In 1984/85, Erdmann became the first German to sail solo and non-stop around the world, then, also with a crew, on the Atlantic, North Sea and Baltic Sea. In 2000/01, he achieved another historic feat with his non-stop circumnavigation against the prevailing wind direction - another German first. He was one of the most important and best sailors in history.

Erdmann lived for and from sailing, he gave hundreds of lectures and his books became bestsellers. On 8 May 2023, Wilfried Erdmann passed away after a serious illness at the age of 83.