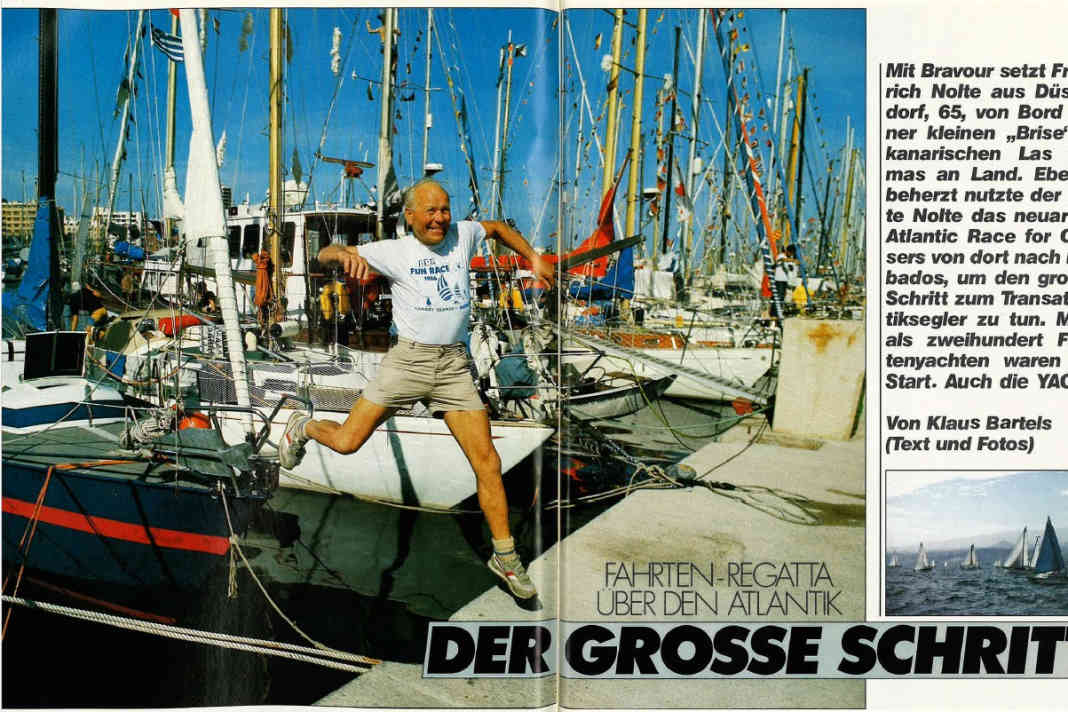

40 years of ARC: The adventurous Atlantic voyage of a YACHT crew in 1986

YACHT-Redaktion

· 21.11.2025

From Klaus Bartels

John and Knud straddle the foredeck of the "Wann-O-Zeven" with stiff movements and hoist the spinnaker. We left the harbour in Las Palmas at 10.00 a.m. - two hours before the start - to familiarise ourselves with the boat again. After all, almost four months have passed since we last sailed together on the Bianca 107.

"Throw out the spifall!" - "Which one?" We're not a well-rehearsed crew yet.

My sea legs are still missing too. As I move towards the forecastle, I hold on with both hands to be on the safe side, and only one hand remains free for the work of hoisting the foresail. Is it because of the heavy swell before leaving the harbour, which is unusual for us Baltic sailors, or because of the wine, which flowed a little too freely last night as a farewell?

15 minutes before the start, the Spanish warship, which is to kick off the regatta with a cannon shot, leaves the harbour and positions itself. John, who has sailed most of the regattas between the four of us, keeps looking at his watch and suggests crossing the line exactly at the starting gun. Skipper Michael, however, doesn't want any stress. I also realise that with a distance of almost 2800 nautical miles, you don't necessarily have to fight for seconds at the start. Owner Knud is of the same opinion. John admits defeat.

Starting signal. We are about the 40th ship to cross the line and set course for the northern tip of the island. The swell increases. My three fellow sailors brace themselves for the sea. They stick scopolamine plasters behind their ears. My stomach feels a little queasy. But I've never got seasick, so I don't take the medication. After two hours, I'm glad I did. John and Michael are experiencing side effects and both complain that they can't see as well. John even keeps seeing cucumbers in the reheated pea soup.

Gran Canaria slowly passes by on the port side. We set the large spinnaker. John at the helm is in his element. The Bianca is travelling at between eight and nine knots. Owner Knud smiles knowingly as his boat sails past others. John is happy about every "overtaking manoeuvre". Only the skipper sometimes looks anxiously at the wind gauge. In one gust, the log even climbs to twelve knots. At 6.00 p.m., at sunset, however, the wind dies down. As darkness falls, the first lights of Tenerife flash across the water to starboard. Still 2750 miles to Barbados.

From the logbook: 18.00; sails genoa, main; course 245 degrees; wind westerly 2 to 3 Beaufort; temperature 19 degrees.

My first night watch begins at midnight. A few lights from other regatta participants can be seen behind us. "We're the first," Knud greets me. We sit together in the cockpit for four hours, but don't talk much. The self-steering system holds its course well in the calm night, and the steady sound of the bow wave has a soporific effect. Time does not want to pass. At 4.00 a.m. when the watch is changed, Tenerife is still abeam.

The whole ship smells of fried bacon when I wake up four hours later. Michael serves scrambled eggs with bacon for breakfast. In Las Palmas, we bought a large piece of bacon, 100 eggs and even an air-dried ham, among other things.

After a lengthy discussion, we decide that the waking times need to be shortened. Three hours is enough.

As soon as the last coffee has been drunk, the 100 square metre spinnaker is set. "After all, we're sailing a regatta," says John. Four hours later, however, the wind has picked up strongly. The large bubble is replaced by the 60 square metre spinnaker. We suffer our first material damage. When setting the light downwind sail, it gets caught on the leech of the battened mainsail and tears.

From the logbook: Barometer 1023; wind 4 Beaufort with gusts; 24.00 hrs calm; temperature 18 degrees.

"When was the last time you travelled as a crew?" John wants to know. It's been years for him too. On your own boat, you always sail as "captain". Because Michael is the only one of us who has mastered astronavigation and has experience on the high seas, we have chosen him as our skipper.

At 06.00 after the first night, I lie down in my bunk. An hour later I'm wide awake again. The ship is rolling heavily. It rumbles below deck, crockery clatters, waves thud against the side of the boat. Although we have bunk sails, you have to claw into the cushions to stop yourself being tossed about.

Wind force 6, sleep is out of the question. In every wave trough, the sails beat back with a loud bang. The mast rattles and shakes.

The Atlantic swell has developed white foam heads. With blister and the main reefed once, the Bianca sails almost constantly at 8 knots even downwind of the wave crests.

The morning scrambled eggs can only be prepared with four hands. Breakfast is eaten on the cockpit floor. However, we are still inexperienced Atlantic conquerors. The egg slips off the plate, coffee cups tip over. For the first time, there is swearing on board the "Wann-O-Zeven".

I have difficulty concentrating and try to sleep for a few more hours. I only manage to do so wedged between the cushions and the bunk sails. Nobody feels really comfortable any more. Sitting is difficult for everyone. I can feel every bone. Michael, who has already crossed the Atlantic four times, comforts us: "It's always like this on the third day."

Shortly after 6.00 pm, the sun seems to fall into the sea. Within minutes it has disappeared behind the horizon. I have drawn up a new watch schedule, which is accepted by everyone. From 6.00 p.m., one crew member is now on watch for three hours at a time. A second man must be on standby with his seatbelt fastened. He can also be below deck. At night, it is an unwritten law that everyone must fasten their seatbelts to the taut line in the cockpit.

The fifth day. When I wake up at 06.00, it's still dark. The wind is still sleeping. The Bianca sails at five knots even in light winds. You can almost no longer hear the popping of the sails in the wave troughs. That's how quickly people can get used to noise. Only Knud looks anxiously into the mast every time the sails strike.

Michael gives me my first lesson in astronavigation. The sun is shining and a light aft breeze is pushing us along. I don't have the feeling that we're moving forwards at all. Hour after hour, the Atlantic looks the same. It seems like a disc to me, the "Wann-O-Zeven" is its centre. The only way I can tell we're travelling is by the ever-lengthening pencil line on the chart. Somehow I still have the feeling that land is about to appear in front of us. Yet there are 2000 nautical miles ahead of us.

A loud bang: the yacht collided with a half-submerged plank. Fortunately, the approximately three metre long piece of wood did not even damage the gelcoat.

From the logbook: 12.00 hrs; Etmal 138 nautical miles; Barometer 1021; Compass course 270 degrees; Temperature 25 degrees.

The doldrums, which almost every Atlantic sailor who sails westwards from the Canary Islands reports, catch up with us in the afternoon. The sun is blazing and the crew are competing in the use of sun cream. According to my initial position calculation, we have still covered a distance of 136 miles despite the balmy winds. The banana plant attached to the pushpit ripens quickly. But the tomatoes are also overripe in one fell swoop. It becomes a fruit and vegetable day.

Because the big spinnaker always collapses, we set our blister. The wind steering system stops working. The wind is too light for the Sailomat. We take turns steering by hand. The lower the boat speed, the more the yacht rolls. At some point, the blister also collapses. Barbados is still a long way off. Should we start the engine? The discussion ends with the skipper's firm refusal: "We're sailing a regatta!" he says, wiping the sweat from his brow and busily fiddling with his sextant. John reads. Knud looks at the horizon.

We recover the blister at 11.00 pm. It's just bobbing up and down on the mast anyway. John stays on watch in the cockpit.

"There's a red light coming towards us," I hear his voice shout. It's 00.30 in the morning. Drowsy, we all move on deck. Sure enough: a red light and, a few metres to the left, a white light. We switch on our navigation lights and wait. I can make out a larger vehicle through the binoculars. I can't make out any details in the darkness. As the "Wann-O-Zeven" shines under position lights and deck lighting, the speed of the two lights decreases.

Michael goes below deck and calls the stranger on VHF channel 16. No answer. The lights slowly circle around us. I try to communicate with the handheld radio. The lights are getting closer. Why is he running a red light to starboard? My heart is beating loudly. I'm scared. Are they pirates? Military? What do they want? Michael rushes to the map table and plots our position with trembling fingers. So he's scared too "We're 300 miles from the African coast," he shouts. It can't be a fisherman. Africans don't take their boats that far out into the Atlantic."

The red and white lights are approaching. "Shit," says John suddenly, "nobody can help us here." His voice trembles. He is also thinking of pirates. Knud suddenly has the halogen spotlight in his hand. However, the ship with the two lights is not yet close enough to be illuminated and recognised. What should we do?

Also interesting:

"We're off," says Michael. When the engine is running smoothly, we extinguish the lights and make a hook to port. The lights follow. "They have radar," says Knud. We steer in the opposite direction. The stranger follows.

Once again I try to make radio contact on channel 16. Without success. We switch on the lights again and continue walking slowly. The eerie pursuer also reduces speed. After a long half hour, a halogen spotlight lights up over there. A bridge and a mast with aerials can now be recognised.

Knud lights up our ship. "He's staying behind," John shouts and pushes the engine lever to "full power". We look at each other and visibly breathe a sigh of relief. What was that all about? The two lights follow us until dawn. But the distance is getting bigger and bigger. When the sun rises, there is no one to be seen.

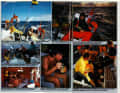

The eerie encounter is the topic of conversation on board for days. We will probably never know what it all meant. At midday on the sixth day, black clouds gather. The spinnaker is recovered. And then suddenly it's there, the wind. First 3, now it's 8 Beaufort. The Bianca lays over far to leeward. We have to reef. It's hard work in the strong wind and the lashing rain. It takes ten minutes to tie in the third reef. The wind keeps ripping the sail out of our hands. The wind is right against the big swell. It gets higher. A second wave builds up. Lots of green water comes on deck.

As quickly as the wind came, it completely fell asleep after an hour and a half. But the waves remain. We set the large genoa and reef out. However, the boat barely makes any headway. Instead, the seas hit us. The port and starboard foot rails alternately plunge into the water.

Each of us is clinging on somewhere. It seems like an eternity. But after two hours, the wind is back. As the boat's speed increases, the movements become more bearable. We're travelling at eight to nine knots with half the wind. But the sea from astern makes for a rollercoaster ride.

Knud is not feeling well. It's his birthday tomorrow, but he has a worried face and goes to bed at 5.00 pm. John has read through the fourth book since Las Palmas. I'm on watch until midnight. Knud was supposed to take over from me. We let him sleep. The night without a watch is our birthday present.

My watch therefore lasts two hours longer. Time doesn't want to pass. By the time John relieves me at 2.00 a.m., I'm exhausted and tired. I can't even wish him a "good watch". Is this the calm Passat I've read so much about?

Today is the 7th of December. The sky is overcast all day. House-high waves with breaking crests make our 10.70 metre long yacht seem tiny. The Bianca slides down the mountains at up to twelve knots. There is a terrible noise below deck. It bangs and rumbles. It's hard to stay on your feet. Sleep is out of the question. No matter how well you wedge yourself between the cushions and sails, you'll be awake again in an hour at the latest.

The totally exhausted Michael says: "This can only get better" The start should be a hearty breakfast. However, the movements of the boat are so violent that we are unable to light the paraffin cooker. Even on the third attempt, the spirit for preheating flows out of the stove burning and spills fierily onto the floor. When a sudden violent movement causes burning spirit to splash onto Michael's bare leg, we give up. We have muesli.

"A ship!" John has seen a sail. In fact, we recognise a white piece of cloth ahead. "As well as we've been going," he says, "that must be a big boat. We've certainly left the little ones far behind us."

But then we realise that it is a 30-foot yacht from France. She is waiting with her jib standing back. "Hello, do you have cigarettes?" the French ask over the VHF. Unfortunately, we don't. "Well, I guess we'll be non-smokers then," says the voice resignedly. We also hear that the crew left the Canary Islands three days before us. They want to go to Martinique. No - they hadn't heard anything about the "Race" and hadn't seen any other ships either - should we be so far ahead?

From the logbook: 12.00 noon; Etmal 158 miles; barometer 1022; course 244 degrees; temperature 24 degrees, two sperm whales to starboard; wild rolling.

The trade wind presents itself from an atypical side. Its direction is right, but it is interspersed with strong gusts and rain showers. However, we make good progress. Our Etmal: 184 miles. Reason enough to get a bottle of wine out of the back box. But I don't like it. The others also sip listlessly from their glasses.

John reads the sixth book. At 6.00 p.m. sharp, the great sovereign on board, the new watch schedule, which is pinned up with 'Tesaband' above the navigation corner, is in charge. It has become a habit for me to hand everyone a piece of paper with their watch times, relief and standby times written on it. Everyone has six hours to rest at night.

More on the topic:

We've been travelling for 13 days now. Knud needs a tranquilliser. He can no longer sleep because the ship's movements are too violent and irregular. We have calculated that the Bianca has been travelling on average two knots faster than her hull speed for the past two days. The ship obviously doesn't mind. But for us as a cruising crew, it is an ordeal.

Never before in my life have I seen waves as high as today. With the main reefed and the small genoa unfurled, we sometimes roar down the crests of the waves for minutes on end. The wind self-steering system is overwhelmed. We have to steer almost constantly by hand.

Another two days have passed without being able to light the cooker. We eat muesli, brown bread from the tin and slice off pieces of dried ham. It no longer tastes good to me. A tin of liver dumpling soup turns out to be completely inedible, which we open and try unheated. It flies overboard.

John makes an extrapolation: 'If the wind stays like this,' he says, 'we'll reach our destination in six days' Michael doesn't want to give a forecast for another three days. Knud is feeling poorly. He needs to eat something warm. He's still the only one with a plaster behind his ear to prevent seasickness, and when he's not on watch he's usually lying in his bunk. I think he takes tranquillisers every day now. John reads - as always.

We have completed an Etmal of 176 miles. This time we celebrate with a can of beer. It's the fourth in days. As we take our first sip, a large wave knocks one of the two solid-fibre waistcoats out of its holder on the pushpit. The safety line must have worn through. I look at my watch. It only takes 30 seconds before the bright red waistcoat is no longer visible. Bad prospects in case someone goes overboard...

For over a week now, we've had winds of 5 to 6 Beaufort during the day and up to 8 Beaufort at night. You get used to it. The two of us try to light the cooker again. Burning spirit spills onto the floor. I play fireman with a wet towel. When the stove is finally preheated and burning, the crew are annoyed for the first time. Michael had insisted on the paraffin cooker. The rest of us wanted a modern gas cooker. There would have been no such problems with that. That's our opinion. The skipper remains silent.

John asks if I can lend him a book.

The Bianca pulls her course at ten knots. Although the waves have white peaks, spray rarely comes on board. During my midnight watch, a particularly dark cloud approaches from astern. As always, it means more wind, although the air pressure remains constant. The barometer is almost always at 1022 hectopascals day and night. Then it suddenly starts to rain. This time, however, the drops are bigger and then it starts. One minute it was blowing at 5 Beaufort, 30 seconds later it's 7, then 8.

The wind gauge continues to climb to 9, then even to 10 Beaufort. It howls in the rig. On the next wave, the ship accelerates from eight to 15 knots - says the log. It is too late to retrieve the small genoa. There is also no time to pack up the double-reefed main. Michael and John shout into the wind from the companionway: "Stay on course, stay on course!"

What else can I do? The frantic journey never ends. I stare at the wind magnifier. The wind must always come from astern. Always steer in such a way that the small line of the wind magnifier stays on course. Concentrating on the small line is exhausting. Have we been surfing for an hour or just ten minutes? I don't know. It seems like an eternity to me.

The howling in the rig suddenly stops. The wave passes beneath us and the "Wann-O-Zeven" is only sailing at nine knots. I look at my watch. The insane planing took almost half an hour. My limbs are heavy as lead. Wordlessly, I hand over the tiller to Michael. As I lie in my bunk, I ask myself for the first time what the point of the endeavour was.

From the logbook: 12.00 noon; Etmal 188 miles; barometer 1021; course 270 degrees; high, steep seas, showers; temperature 25 degrees. Still 720 miles to Barbados.

The mood on board is at rock bottom. The constant strong wind is getting on our nerves. Even for Michael, who has done this trip twice before, it's a new experience. Where is the cosy trade wind sailing? Even at breakfast, someone now has to take the helm. The wind steering system has finally given up the ghost. The pendulum rudder has broken off completely. The forces generated during the rapid descents were obviously too strong. Without the automatic system, however, we get closer to our destination more quickly.

Knud feels better for the first time in days. Presumably because the days at sea can be counted on one hand. Somehow we have also got used to the strong wind, the huge waves and the nightly "instrument flights". However, the exertion has clearly left its mark. My trousers are sagging. I've lost at least two to three kilograms.

From the logbook: Etmal 175 miles; course 260 degrees; wind 5 to 6 gusty; temperature 26 degrees.

On the penultimate night, the black clouds provide a new variation. The wind not only freshens up to 8 Beaufort, but also turns over 30 degrees. So far, we've never had more than ten degrees of wind shift. When I take over the helm from John, he has just weathered a squall. I didn't notice it. It's been a long time since I listened below deck when the mast shakes and gusts howl through the rigging. Now it's blowing 9 Beaufort and the wind is coming from a completely different direction than the waves.

I pull on the rudder to keep on course. The Bianca runs at an angle to the wave. The boom dips into the water again and again. Cross seas have formed. Spray splashes into the cockpit from all sides. I stare at the wind magnifier. It's like a game of skill. But here the game is serious. When the line of the wind magnifier moves out of line, the mainsail backs. It has already happened a few times on previous days. The bullstander was torn out of the self-tailing winch, it banged terribly, but fortunately everything remained intact.

What happens when the boom bangs around in these 9 Beaufort winds? It can't: I have to concentrate completely on the small line. The boom dives deep again. A wave sloshes into the cockpit. The water runs into my collar. The wind shifts again. I curse and scream.

From the logbook: 12.00 noon; Etmal 167 miles; course 240; showers with hard gusts, cross seas; barometer 1021; 165 miles to Barbados. Temperature 28 degrees.

The Atlantic wants to reconcile us on the last day. The sun is shining and the wind is blowing at 4 Beaufort. At last we can eat like normal people again - each of us from our own plate. The big spinnaker is to be set after breakfast. However, a small dark cloud is gathering behind us. We are damaged by the Atlantic. We stare mesmerised at the cloud. Knud says what we're all thinking: "Let's wait a little longer with the spinnaker"

Only when the clouds have cleared does the downwind sail go up. As there is no cloud to be seen at night either, the spinnaker stays up for 24 hours for the first time. It will be a cosy night watch. In view of the approaching destination, we even treat ourselves to a bottle of wine. This time it tastes good.

I had actually imagined the Atlantic crossing in the trade winds to be like this day. The next morning, a groovy samba sounds over the ship on the ultrashort wave. Barbados says hello. It's 08.00 there and already 28 degrees according to the radio. We chill a bottle of champagne with a wet towel. Knud sits in front of the mast and just keeps an eye out. Where is the land?

Navigator Michael comes into the cockpit and announces: "20 miles to go." It turns out to be 40 miles. But then we see the island. Knud sings, John laughs, Michael wants to eat three steaks and drink two bottles of red wine on arrival. The champagne bottle circles. The heavy nights at sea are almost forgotten.

From the logbook: Wednesday, 17 December; wind 3 to 4 Beaufort, sunny; barometer 1022, crossing the finish line at 18:05. At sea 18 days, nine hours, eight minutes. Distance 2740 miles.

We are the 39th of 205 boats to arrive in the dark. More than 100 yachts had a longer waterline than our "Wann-O-Zeven" They should have been there before us in these strong winds.