Distress at sea from a rescuer's point of view: Operation in dangerous surf in Normandy

Ursula Meer

· 13.05.2025

The harbour within sight - and yet out of reach

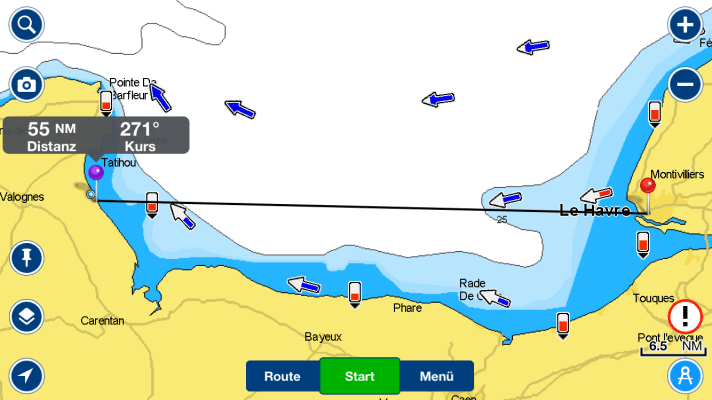

Stormy wind from the north-east. Three metre waves. A ten-metre boat heading for a tidal harbour in the west of the Bay of Seine. On board are three men in their sixties, who have probably had a tough day: more than 50 miles in wind and waves since Le Havre, with and against the current, past rocks and over shallows. Close to the shore, the water depth drops abruptly, the waves become steeper and the tidal current moves the boat across the eye of the needle into which they want to manoeuvre their boat under engine power - the tidal harbour of Quinéville, the entrance to which is metres dry at low tide. The three of them, including the Portuguese new owner, want to transfer the boat, which is registered in Duisburg, from the Netherlands to Portugal.

Walkers on land recognise the precarious situation

Those familiar with the area can guess at this point that the sailors are in an extremely unfavourable position. Close to shore, the small Vindö named "Sasuka" becomes a plaything of the forces of nature. Walkers on the beach observe what is happening and alert the regional coordination centre CROSS Jobourg, which informs the SNSM (Société Nationale de Sauvetage en Mer) sea rescuers from the Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue station, around four miles away, of the sailors' precarious situation.

When the rescuers contact the sailors by radio, they do not feel in any danger. They explain that they have put on their lifejackets and refuse further assistance. However, the situation deteriorates rapidly when the keel of the boat hits hard sand for the first time in the heavy seabed. Running out to sea against the wind, surf and tide is impossible. The boat is pushed further onto the sandbank with every wave.

Rescue mission against your will

The French sea rescuers know how treacherous their area on the edge of the English Channel can be and decide to help the sailors. In order to be able to act as quickly as possible, they deploy a multi-pronged operation: while a RIB with the station manager and two lifeguards approaches the stricken ship at sea, three experienced rescue workers - a diver and two lifeguards - simultaneously make their way to the scene of the accident by land. Meanwhile, a helicopter with another diver on board is also circling over the scene.

When they arrive, they quickly recognise the critical situation. The Vindö is aground in Legerwall and is being violently tossed back and forth by the heavy surf. The rescuers decide to evacuate the three sailors immediately. The rising tide, the approaching darkness and the powerful surf make rescue from the sea impossible. Even a possible rescue by air would be too dangerous in view of the constantly unpredictable movement of the mast.

The only rescue route turns out to be the one between the nearby shore and the casualty. From the beach, the diver and the two lifeguards enter the surf. The RIB remains on standby nearby in case the occupants of the sailboat fall into the water and are swept out to sea. The RIB and helicopter coordinate the daring operation by radio and guide the three rescuers to the "Sasuka". All three sailors can be rescued and brought ashore on foot. Apart from slight hypothermia, they are unharmed.

The rescuers have to go through the surf again

While they are driven to a hotel for the night, the rescuers have to make their way through the surf to the stricken ship once again. They make sure that there are no emergency transmitters on board to cause a false alarm, and then they set the boat's anchor. But it cannot withstand the wind, which continues to freshen as the night progresses, and "Sasuka" is washed up on the beach. At the worst possible time: the tidal coefficient, and therefore the water level at high tide, was rising, as was the wind, which was blowing strongly from the east, further increasing the water level at the time of the accident. At the time of the accident, salvage from the sea is considered impossible in the long term. According to SNSM estimates, the boat should not have sufficient water under its keel again until the next spring tide at the end of April at the earliest. In view of the stormy seas, the return journey of the SNSM RIB will be monitored from the air by helicopter as a precaution.

Honouring the brave helpers

The SNSM rescuers work in an extremely challenging area, and missions of this kind do not always end so smoothly - for the rescued as well as for the rescuers. All six sea rescuers involved have decades of experience and have carried out hundreds of rescue missions. But this one required so much courage in the face of extremely adverse conditions that station manager Bernard Mottier has now nominated them for the "Medal for Dedication and Rescue Acts".

Never underestimate the territory!

The accident once again illustrates how quickly harmless trips can turn into life-threatening situations. The SNSM therefore urgently warns against underestimating the effects of the strong tidal range, strong currents and high surf waves along the Norman coasts. Sailors should always check weather and tidal information carefully. The approaches to the tidal harbours repeatedly prove to be life-threatening traps in such adverse conditions. "The harbour of Quinéville is absolutely to be avoided for keelboats, as it is very difficult to access with its narrow channel and low water level. It is also dry at low tide," explains Bernard Mottier.

A plan B before departure is therefore essential. In this case, for example, the safer options would have been to weather out at sea or to call at the harbour in nearby Saint-Vaast-La-Hougue, which is protected by a long breakwater. Depending on the tidal coefficient, the harbour is open from around 2.5 hours before to 2.5 hours after high tide. Around low tide, harbour gates keep the water level in the harbour. However, Bernard Mottier recommends: "Sailors caught in a storm can anchor in the area between Tatihou Island and Le Hougue until the harbour gates are opened. Under these circumstances, anchored sailboats have visual contact with the semaphore of La Hougue and can contact the CROSS Jobourg at any time via VHF channel 16." In such weather conditions, there is no safe harbour on the east coast of the bay other than the port of Saint-Vaast.