Baltic Sea: Swedish Maritime Administration warns of large-scale GPS disruptions

Hauke Schmidt

· 28.06.2025

The Baltic Sea is increasingly becoming a theatre of hybrid warfare, presumably originating from Russian military bases. In addition, the shadow fleet is suspected of being involved in jamming the satellite signals. There is no doubt that reception is at least temporarily disrupted, and German naval units have also reported long-term failures of satellite-based navigation during manoeuvres in the Bay of Gdansk. Nevertheless, the exact extent of the interference is difficult to estimate. The civilian sources are often based on aircraft observations, which do not provide a clear picture of the situation on the ground, and the military findings are rarely made public.

Previous reports of interference with GNSS systems:

With the recently issued communication, the Sjöfartsverket is expanding its official warning significantly. The southern, central and northern Baltic Sea as well as the Gulf of Finland and the Åland Sea are affected. According to the authorities, GPS malfunctions have been reported many times during the spring, which is why an official warning is now being issued, which is also being disseminated via the notices to mariners.

GPS disruptions have increased tenfold in the last year

The Finnish road safety authority Traficom takes a similar view. It also warns of unreliable satellite reception in Finnish waters. From a current Report shows that the number of reported incidents increased tenfold last year to around 2800. This spring, around 630 incidents have already been reported. Furthermore, the disruptions are no longer limited to air traffic.

In shipping, there were hardly any GNSS interference reports from Finnish territorial waters before 2024. In the summer of 2024, GNSS jamming occurred more frequently, especially in the eastern Gulf of Finland in the Kotka-Hamina area, as this area is close to the Russian border and has a high volume of traffic. The reports of GPS interference come mainly from commercial shipping. The authority has only received one report from a yachtsman.

How to recognise GPS faults

Practically all known incidents to date have involved so-called jamming, i.e. the comparatively weak satellite signal is virtually drowned out by a powerful jammer. In practice, this means that the receiver can no longer analyse the signals and loses the satellites. As all systems operate on very similar frequencies, jamming affects all systems, so it doesn't matter whether you use GPS, Beidou, Galileo or GLONASS.

The fewer satellites are available to determine the position, the less accurate the position becomes, until the satellite tracking is completely lost. Signs are a jumping position of a few 10 to 100 metres. However, this is difficult to recognise in the usual zoom levels on the plotter. Jumping positions distort the calculation of the speed over ground (SOG), which is why unusually fluctuating speed displays are a clear indication. A look at the satellite overview also helps. If only a few satellites are still being used for navigation, a fault is likely. It should not be forgotten that the GPS position is also used by other devices, such as the AIS. Even if your own ship still has a clean position, the AIS signal of another yacht or a freighter may send the wrong position and therefore be displayed in the wrong place on the plotter.

What to do if the GPS fails

Sjöfartsverket and Traficom have issued a series of recommendations for action in the event of interference with satellite reception. They are not specifically aimed at sailors, but some of them can also be implemented on yachts:

- Be aware of the risk: GNSS interference can occur at any time and anywhere in the Baltic Sea. The risk is highest in the Gulf of Finland.

- Actively monitor the safety warnings for maritime traffic!

- Recognise dependencies: Find out which systems on board rely on GNSS data (e.g. position, course, speed, time).

- Use alternative systems: Regularly use navigation methods that are not dependent on GNSS, such as radar and paper/electronic charts. Use gyrocompass and logbook as required.

- Create an emergency plan: Prepare and practise alternative procedures for navigation in the event of GNSS interference.

- Recognise interference: Learn to recognise GNSS interference, both spoofing and jamming.

- Not all interference means a total loss of signal, and in the case of spoofing, the navigation systems cannot recognise the falsified information.

- Know the support along the route: Include in your passage plan the stations (e.g. VTS and SRS centres) that you can contact if GNSS becomes unreliable.

- Switch to visual and radar navigation: If GNSS is impaired, steer manually. If no gyro information is available, use the head-up radar mode.

- If necessary, deactivate navigation functions that require a heading input.

- Report any incidents: Notify the coastal state authorities (e.g. VTS and SRS) of any incident detected.

- Watch out for others: Even if your vessel is not affected, nearby vessels may be affected by GNSS interference.

- Stay alert and be ready to help or adapt accordingly.

Study from Poland points to mobile jammers

Previous investigations into GPS interference have been based on individual reports and the ADS-B data recorded by aeroplanes, which are used to create the maps on gpsjam.org, for example. The major disadvantage of this is that due to the quasi-optical propagation of the interference signals, it is unclear to what extent reception on the ground is hindered by the signals detected in the air, as the range of a ground-based interference transmitter is limited by the curvature of the earth, regardless of its transmission power.

In a Studywhich was carried out between June and December 2024 by the Gdynia University of the Sea together with the private company Gpspatron, an analysis receiver installed on the ground was used. The site is located around 35 kilometres from Gdansk and 120 kilometres from the Russian oblast of Kaliningrad.

The scientists also recorded longer GPS disturbances of over seven hours, which they believe significantly impaired GNSS-based navigation. They found a significant deterioration in positioning accuracy, with errors increasing from the original 3 to 5 metres to around 36 metres. However, according to the study, there is no link between terrestrial GNSS interference and effects on the ADS-B air traffic control system. This highlights the disadvantages of relying solely on airborne surveillance systems in the face of threats to ground-based infrastructure.

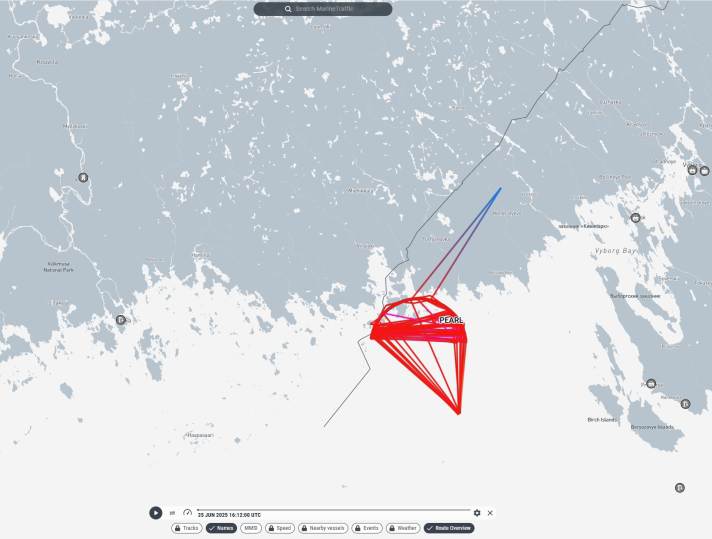

The team also reports "clear evidence of mobile maritime sources of interference" in international waters. These showed movement patterns "that correspond to ships in the Baltic Sea". It is suspected that tankers from the shadow fleet are also being used as transmitting stations. In addition, the jamming signals have a very complex structure, which would indicate a military origin. Commercial systems for jamming satellite-based trackers have much simpler signatures.

The correct use of compass and map:

Hauke Schmidt

Test & Technology editor