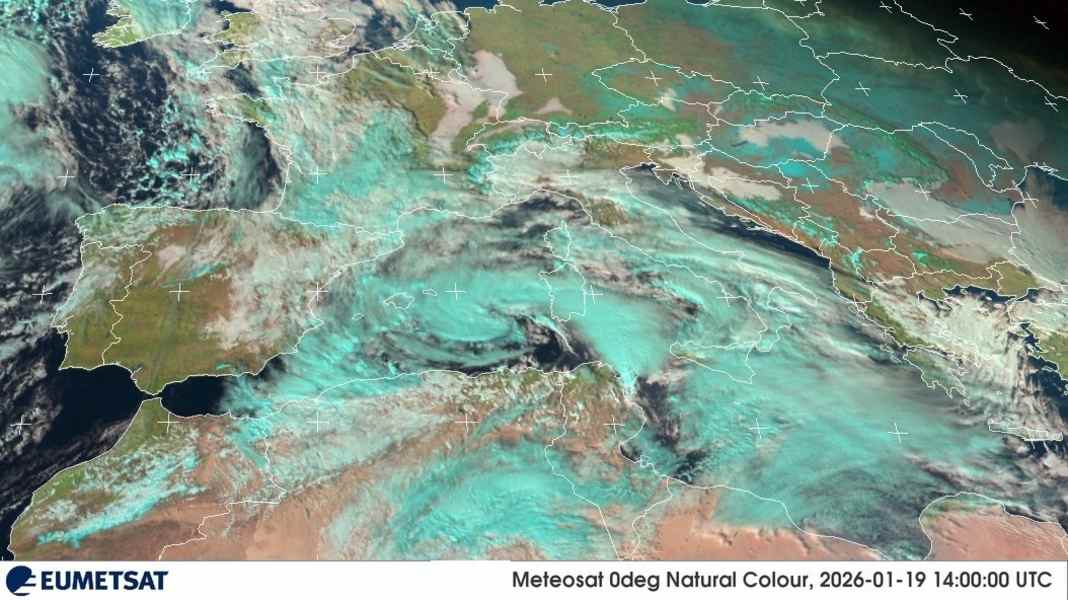

What "Harry" was meteorologically

In everyday life, the term "cyclone" is often used to describe a storm that forms over warm water. In meteorological terms, however, this term is much broader. A cyclone is simply a rotating low-pressure system, i.e. a large-scale wind circulation around a low-pressure centre. In the northern hemisphere, this circulation rotates anti-clockwise. This means that the lows that characterise our winter in Europe also fall under this definition - although we usually call them "lows" or "storm lows", not cyclones. To be precise, "Harry" is a named, powerful Mediterranean low, i.e. a Mediterranean cyclone. The term "Medicane" (Mediterranean hurricane) would be possible if a stable warm core and a relatively symmetrical structure were detected - however, this is a subsequent diagnosis based on analyses and cannot be derived from spectacular satellite images.

The development of extreme weather

The particular intensity of storm depression "Harry" can be explained by the interplay of various meteorological factors. The depression established itself over the western Mediterranean and drew in very moist and warm air masses. These air masses absorbed additional energy over the comparatively warm Mediterranean, which increased the intensity of the storm. A decisive factor for the extreme weather situation was the blockade by stable areas of high pressure further north, which prevented the system from moving away quickly. As a result, the depression remained almost stationary for several days, and areas of rain repeatedly moved across the same regions. Many strong Mediterranean systems do not start out "tropical", but rather classically dynamic. A cold air trough often initially lies high up, which separates from the main flow band as a so-called cut-off low. In addition, a low forms near the ground, which is fuelled by temperature contrasts and uplift at fronts.

Climate change as an amplifier

Italian meteorologist Mattia Gussoni from the weather service ilMeteo.it emphasises that winter storms over the Mediterranean are not an unusual phenomenon in themselves. "There have always been winter storms over the Mediterranean," explains the expert. However, such storms are occurring "more frequently and more violently" as a result of climate change. Gussoni cites the increased water temperatures in the Mediterranean as the main cause of this development, which provide the storms with additional energy. In the case of "Harry", the mild water temperatures played a decisive role: "The mild water temperatures are a source of energy and lead to higher evaporation. For this reason, 'Harry' became an extreme event, the likes of which we have rarely experienced in the past," emphasises the meteorologist. The higher rate of evaporation over the warm water led to more moisture in the atmosphere, which was eventually released as heavy rain.

Where the high wind speeds came from

At its core, wind is the atmosphere's response to pressure differences. Air wants to move from higher to lower pressure, is deflected on the rotating earth and then flows around the low. The denser the isobars, the stronger the pressure gradient, the higher the wind potential. In the Mediterranean, there is an additional amplifier that is very familiar to skippers: jet effects and channelling. Between islands, along capes and in narrow passages such as the Strait of Sicily, the wind accelerates locally, even if the large-scale averages sound less dramatic. Specific peak values for "Harry" are well documented, at least for Malta. The Maltese weather service reported 56 knots in Valletta, around 104 kilometres per hour - a wind force at which it is no longer "just" lines working in marinas, but infrastructure becomes critical.

Why so much rain fell

Heavy rain needs two things: a lot of water in the air and a mechanism that lifts this air strongly. Mediterranean lows provide both. Over the sea, the lower air mass is constantly recharged with moisture through evaporation. If this moist air enters the circulation of the low and is lifted by fronts, convergence zones or orography, it condenses. In extratropical cyclones, the most important rain engine is often the so-called warm conveyor belt, a broad, ascending air stream that converts large amounts of moisture into clouds and precipitation. Studies on Mediterranean cyclones show that the warm conveyor belt and deep convection play a central role in heavy precipitation. Warnings of very high 24-hour amounts were issued in many places in the area of influence of storm depression "Harry". Media reports in southern Italy and Sicily cited amounts of over 100 millimetres in 24 hours as expected in the warning areas.

Why the waves got so high

The wave height is not a product of chance and is not only dependent on the wind force. Three factors determine how much energy is pumped into the swell: Wind speed, duration and fetch, i.e. the uninterrupted distance over which the wind blows over water from one direction. Large waves only occur when all three factors come together. In the Mediterranean, the fetch is often limited because land masses are quickly in the way. This makes the specific wind direction all the more important. Long easterly to south-easterly winds can run over open water for hours to days before they hit the coast. Then the wind sea turns into a heavy sea with pronounced swell, which subsides even when the wind has already shifted or died down. This is precisely why harbours are sometimes more dangerous than the open sea. Swell can run around capes, reach over piers and build up in the harbour basin.

Various dangers from the storm depression

The intense rainfall was particularly problematic during this low, reaching exceptional levels locally. In coastal regions and the mountainous hinterland, this quickly led to flash floods, overflowing rivers and landslides. The danger was further exacerbated by heavy squalls in some places. The high swell made shipping considerably more difficult and caused damage to coastal infrastructure. Sicilian weather channels, referring to a measuring buoy from the ISPRA wave measuring network, report a maximum individual wave of around 16 metres in the Sicilian Channel - a value that explains why even robust port facilities were pushed to their limits. Added to this is the water level: when the air pressure is low, the sea level rises slightly locally (inverse barometer effect) and strong winds push additional water onto the coast.

Impact on coastal and inland regions

The effects of storm "Harry" hit both the coastal regions and the interior of the country with full force. On the coasts, metre-high waves caused erosion and damage to beaches, promenades and harbour facilities. Many ships were thrown ashore. In some places, the strong surf reached the first rows of streets in coastal towns and flooded shops and homes. At the same time, the extreme rainfall in the hinterland led to a rapid rise in water levels in rivers and streams. In Catanzaro, the capital of Calabria, which lies around 20 kilometres inland, streets turned into raging torrents. Several people had to be rescued from their homes or cars, which had been trapped by the masses of water. The combination of heavy rainfall and the masses of water coming from the mountains further exacerbated the flooding. In urban areas, the sealed surfaces significantly exacerbated the risk of flooding, as the water was unable to seep away and collected in streets and low-lying areas.

More articles on wind, weather and seamanship

- The 16-metre wall: Cyclone "Harry" destroys marinas in Sicily and Malta

- In distress: Sailor stranded in icy Elbe mud during storm "Elli"

- Seamanship: Storm in the harbour - how to secure your yacht

- SailGP: Storm shock in Sydney - SailGP fleet badly hit

- Seamanship: This wind pressure is generated on yachts during storms