Seamanship: MOB manoeuvres with on-board equipment only - the instructions

Michael Rinck

· 16.11.2023

It's every sailor's nightmare: a crew member goes overboard. Frighteningly quickly, the person is left in the wake, even if the crew reacts quickly and initiates a rescue manoeuvre. The biggest concern at first is losing sight of the person in the water. Only the head of a floating person peeks out of the water - very little to make them out in choppy seas. However, the more time the search takes, the more the casualty cools down.

Everyone has practised the buoy overboard manoeuvre as part of their sailing training; it is an integral part of the sailing licence test. The buoy is quickly brought back on board with the boat hook. But when a boat has finally been steered safely alongside a person floating in the water, the real-life difficulties begin: How do you get them back on deck? The specialised trade has safety equipment ready for such cases.

The market offers everything from buoys, nets and rescue collars to systems that can pull casualties out of the water almost autonomously.

If no recovery system is available for the MOB manoeuvre

However, not all boats are equipped with such equipment. Charter boats, for example, usually only have the mandatory safety equipment such as lifejackets and lifelines. And the situation is often no different on private sailing yachts.

This is precisely the premise behind the safety training organised by the Bremen Sailing Association. Led by August Judel, it took place off Hooksiel, together with employees from "Fire & Safety" from the training centre in Elsfleth. "Recovery methods with on-board equipment and without special equipment" was on the programme for the training measure, which we accompanied.

The scenario was played out with one rib, two yachts and a handful of volunteers in wetsuits. There were always enough hands on deck to prepare a halyard or a sling to get the person out of the water. What's more, the wind was very light that day and there were no waves.

Conditions were almost too easy, and yet: despite a large crew and favourable weather, problems quickly became apparent that could lead to a life-threatening situation in an emergency. First and foremost, the crew is of course well prepared for an exercise: The individual steps were discussed on land and, more importantly, there is no surprise effect when a volunteer drops into the water.

The best MOB manoeuvre doesn't even have to be performed

The first important point, observing the emergency situation, alerting the crew and initiating the MOB manoeuvre, can be a major challenge with a small crew. For example, if there is no one on deck who is even aware of the accident. This is why prevention is extremely important, especially for small crews or when travelling at night: keeping yourself on a leash does not always prevent you from going over the railing, but at least there is still a line connection to the ship.

The next point concerns the lifejacket. It prevents you from drowning, which would happen without a lifejacket if you lose your strength or become too chilled. It also increases visibility, even at night with lighting. And thanks to the integrated lift harness, it is the easiest way to get an exhausted person out of the water.

Technical aids such as emergency transmitters (Personal Locator Beacon, PLB for short) on the lifejacket or immediately marking the MOB position on the plotter can help to find your fellow sailor again. If the crew has been alerted and a lookout is manned, depending on the location of the accident, contact the rescue services by radio or, if close to the coast, by mobile phone. If their intervention is not necessary, an emergency call can be cancelled. This is better than waiting too long to make a mayday.

Control during the MOB manoeuvre

The second major challenge is to steer the boat back to the casualty. Even if the manoeuvre has been practised a lot, it is often not easy to stop a yacht right next to a person floating in the water.

This is why we recommend always starting the engine as well. It helps with steering, stopping or not losing speed too early on the last few metres.

If in doubt, all sheets can simply be cast off and the boat can be motored alone. In this case, however, the crew must be extremely careful not to be hit by a sheet that flaps around or even by the main boom swinging back and forth.

The last section to the person in the water is the most critical. There must be sufficient speed in the ship, but the casualty must not be run over under any circumstances. Steering is made more difficult because the helmsman can no longer see the head of the co-sailor as soon as he is close to the side of the boat.

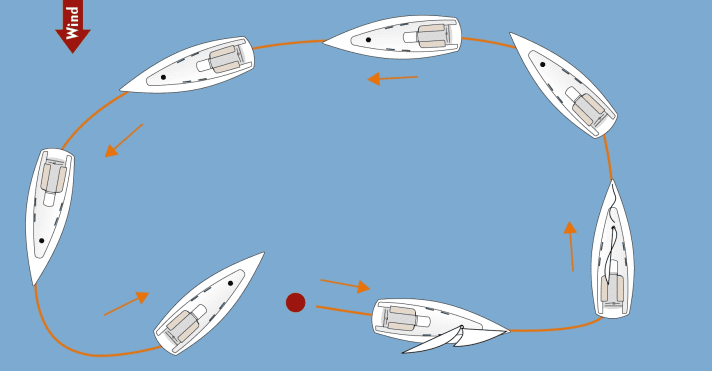

Which manoeuvre to control

Here the exercise has shown that the Munich manoeuvre is ideal, where the jib stays astern: The yacht drifts slowly to leeward in the direction of the overboard manoeuvre. Here, too, the engine is a great help. Slight thrusts forwards or backwards ensure that you do not drift past the right place.

However, it is essential to practise this manoeuvre on your own boat beforehand, as every yacht behaves slightly differently.

The most important part follows: the person must somehow get out of the water and back on board.

Recovery during the MOB manoeuvre

The first step is to throw a line to the casualty in order to establish a connection to the boat. In the simplest case, the person still has strength so that they can be led to the stern with the line and can be rescued on their own using the swim ladder, for example. If the sea is too rough and the stern is pitching, or if the person in the water is too exhausted, only a rescue ladder amidships or winching up will help.

Improvised aids

During the exercise on the Jade, it became clear that a lot can go wrong. For example, communication from the helm to the foredeck is not easy; hand signals usually work best. In addition, the spinnaker halyard proved to be too short, it did not reach down to the surface of the water. The snap shackle was also so stiff that it could not be opened with wet fingers.

Here too, it is therefore important to practise MOB and recovery manoeuvres with your own boat again and again in order to be immune to unpleasant surprises in an emergency. Above all, arrange hand signals in advance. And check shackles, sheets and halyards regularly.

Winching up the MOB is a feat of strength

Once the halyard is hooked into the lift loop on the casualty's lifejacket, he has to be winched up. This is extremely strenuous! Halyard winches are usually smaller than those for genoa sheets. In addition, the halyard may get jammed between the pulley on the masthead and the sheave box as it is pulled very far to the side.

To avoid this and to make winching itself easier, a block and a mooring line or a fore sheet can help. The block is attached to the halyard and the genoa sheet or mooring line is threaded through it. One end is attached to the winch and the other is used to pick up the person. If a mooring line is used, it must also be threaded through the hollow point so that the angle of pull to the winch is correct. In this way, the genoa winch can be used for hauling up.

What many people don't realise is that the person has to be winched up so far that they can get over the railing. However, there is a risk that the person will sway strongly when the ship moves and hit the shrouds, mast or main boom. This becomes even more of a problem if the person is recovered horizontally. In this case, fellow sailors on the running deck are enormously helpful, guiding the casualty while he is still suspended in the air.

Practise MOB manoeuvres again and again

It is also possible to rescue a person from the water single-handed, we tried it out. However, this requires a lot of practice beforehand. The Dehler 36 also had an electric winch. This simplified the procedure enormously, especially as it could also be operated from the steering wheel. Nevertheless, experience off Hooksiel shows that rescuing a crew member who has fallen overboard quickly becomes a challenge, even with a crew. Especially when improvisation is required.

But even if the sling is already ready to be winched up, a rescue can fail due to details such as incomprehensible commands, jammed shackles, lines that are too short or restricted visibility at the helm. It is therefore strongly recommended that the manoeuvre sequence is discussed and trained in detail.

A fender will then suffice for the time being. However, it can't hurt to consider which line would be suitable for a rescue loop in an emergency: lines with a larger diameter cut less. It is therefore best to choose the thickest mooring line.

Read here how you can provide first aid in the event of injuries:

Communication barriers can be overcome if everyone knows what to do in an emergency and hand signals have been agreed. There is also a precise distribution of emergency roles: Who takes the lookout and shows the helmsman the way, who starts the engine, who makes the emergency call, who releases the sheets at the right moment?

It's best to schedule a practice session every season. If the crew makes time for it, it is guaranteed to be an exciting day - which gives everyone the good feeling of being prepared for an emergency. But the most important tip remains: Pick up and put on your lifejacket!

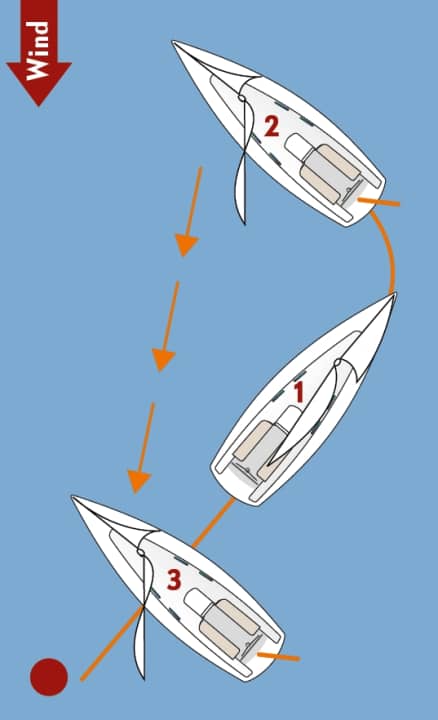

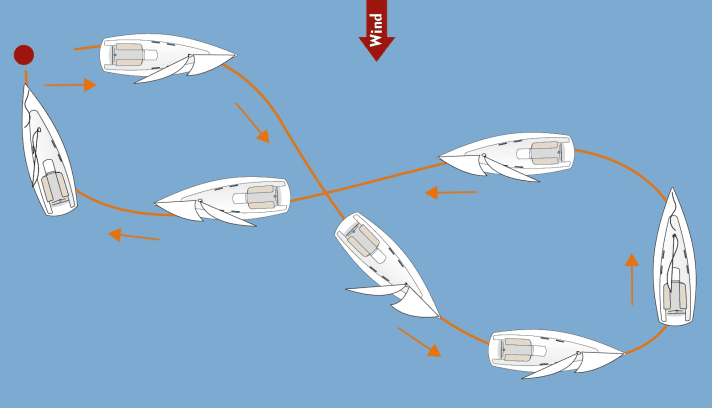

MOB manoeuvre step by step

3 Salvage methods

The best MOB manoeuvres

Munich manoeuvre

Q-turnaround

Under machine