Seamanship: How a British crew made it safely ashore with the emergency rudder

Morten Strauch

· 19.02.2026

Losing the rudder is one of those horror scenarios that nobody wants to experience. An unmanoeuvrable boat, whether close to the coast, in a busy shipping lane or in the middle of the ocean, is always an extremely threatening situation for the boat and crew. If water ingress occurs in the area of the rudder suspension, a boat can often no longer be saved and will sink mercilessly.

Read our special articles on the subject of "Loss of rudder" here:

- Notruder: What to do if you lose your rudder - we tried it out

- Safety on board: Prepared for emergencies - 6 checklists for 6 scenarios

- Sinking after rudder loss: Owners report how they experienced the accident involving their Arcona 460

- Interview: Pensioner rounds Cape Horn despite losing his oars

- X-Rudder: Flexible emergency rudder kit, not just for orca interactions

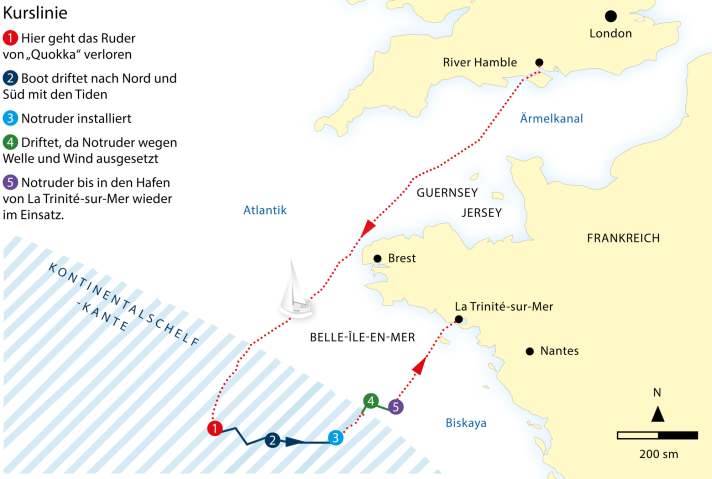

The British crew of the "Quokka" experienced a loss of rudder 200 nautical miles off the French west coast in 40 knots of wind and waves three to four metres high. In addition, several cargo ships were within sight of the unmanoeuvrable boat.

Despite all the adversity, the men developed a plan that brought them safely back to land. Willpower, creativity and a pinch of British gallows humour contributed significantly to their success. Even though this rescue manoeuvre in the Bay of Biscay took place back in 2011, the numerous orca attacks and resulting rowing losses make it more relevant and instructive than ever.

Fifteen years later, the former crew members around skipper Peter Rutter meet in a pub in Hamble-le-Rice in the south of England and recapitulate the dramatic events of that time. "We set off around midnight in October on the River Hamble, just a stone's throw from here. The destination was Malta, to take part in the Middle Sea Race with 'Quokka'." After that, the plan was to take the Grand Soleil 43 to the Canary Islands to sail with a new crew to St Lucia in the Caribbean as part of the ARC Transatlantic Regatta.

The boat is supposedly perfectly prepared for all eventualities. In addition to large stocks of food and drinking water, there is also plenty of reserve diesel in canisters. There is even a water maker on board. "After passing the island of Ouessant at the westernmost point of France, we continued on our south-westerly course in order to be able to sail more comfortably with the wind on the back of a forecast depression," recalls Graham Moody. In the second reef, "Quokka" soon had to deal with three to four metre high waves in 40 knots of wind, which caused no problems for the experienced crew.

Loss of the "Quokka" rudder

But suddenly there is a loud crack and something hits the hull. Scott Dawson is at the helm and shouts: "We've lost the rudder!" The boat turns and chaos reigns for a short time. "While Scott rushed forward to retrieve the headsail, I came on deck and was hit directly by the flapping mainsheet. The boat was unable to manoeuvre, there was water in the cockpit and four cargo ships were bobbing around in the immediate vicinity," says the fourth man in the team, Malcolm McEwen, describing the situation. "Mayday" is hastily dispatched. Eight nautical miles to the south, the freighter "Tinsdale" responds and prepares an evacuation. The distress call is forwarded to the British and French rescue control centres.

Loss of oars on the Bay of Biscay

Once the mainsail has been recovered and it is clear that there is no hole in the hull, everyone gathers below deck to take a breather and assess the situation. The "Tinsdale" is still standing by, but the men agree that an evacuation in this swell would not only be risky, but would also mean the loss of the boat. As "Quokka" was also drifting away from the shipping lane, the crew decided to stay on board and release the freighter from its duty to assist. In a satellite call with the British coastguard, it is also agreed to reduce the "Mayday" call to a "Pan-Pan" message, as there is no longer any immediate danger. Instead, the French rescue service calls up a two-hourly situation and position report.

Skipper Rutter had already gained experience with a lost rudder in the Sydney to Hobart Race. "The big difference to the incident in the Bay of Biscay, however, was that Down Under we had a boat with a straight transom - ideally suited as a support surface for an emergency rudder construction. However, 'Quokka' was a modern racer with an open aft cockpit. So we first had to build a temporary and stable transom."

It is a stroke of luck that an aluminium berth frame fits to close the gap. The robust frame is lashed to the two-part pushpit with ropes. This is no easy task, as the boat lies at right angles to the waves and is constantly tossed back and forth. In addition, excess water enters the ship via the forecastle boxes, which requires regular pumping. A gruelling constant state, sometimes coupled with seasickness.

"Another stroke of luck was definitely my experienced and resilient crew. Malcolm McEwen had a Whitbread Round the World Race in his wake, and with Graham Moody we even had a boatbuilding scion from a traditional shipyard on board." So the next night, Moody tinkered with an emergency rudder construction while his mates took turns resting and keeping a lookout with torches and signal flares.

An emergency rudder is needed

The next morning begins with a cup of tea and a sketch of the rudder that is to manoeuvre the English back to land. Meanwhile, a small aeroplane circles above the "Quokka". The French sea rescuers (CROSS) want to show that they are keeping a watchful eye on the boat and crew. Spirits soar and the men immediately set to work looking for or dismantling the necessary components: two cabin doors for the rudder blade, the rod kicker as a tiller, bolts and every scrap of line they can find.

"It was an ingenious design, absolutely worthy of a boat builder, and we couldn't wait to try out the new rudder," says Dawson. "Still, it was too short, so it didn't stick out deep enough into the water to have any significant rudder effect," Moody interjects with a laugh. So the construction is extended below deck with a storage compartment lid, which is placed between the doors at the lower end. The next problem is grotesque and a hair-raising one: The pimped-up version is simply too big to get out of the saloon again. There is no other option but to dismantle everything and reassemble it outside in all weathers. But with a fighting spirit and a pinch of self-irony, even this minor setback is overcome. "As it was still blowing at 35 to 40 knots, we decided to wait until the wind had hopefully calmed down a bit before we started assembling the boat," explains the former boat builder.

However, there is not much time, as the ship drifts continuously towards the continental shelf, where the water depth drops abruptly from 4,000 metres to 200 metres. The long Atlantic waves can pile up dramatically here and finally seal the fate of the already battered boat. But Fortune was kind to the brave Brits, and 40 nautical miles off the shelf, the rudder construction was finally lifted with the main halyard and carefully guided to the temporary transom. There, around 100 metres of various ropes and straps are used to effectively lock and permanently secure the emergency rudder.

Giving up is simply not an option

To be able to move the mighty tiller freely, only the two steering wheels need to be removed. The only thing missing is a suitable spanner to loosen the tight 45 mm nuts. Rutter, a surgeon by profession, overcomes this problem with hole saws that can be put over the nuts and pressed into shape with pliers. Giving up is simply not an option. Creativity and absolute determination are required.

"With great excitement, we finally started the engine to see if we could stay on course. And it worked! We couldn't get the grin off our faces," says Dawson, describing the turning point of their little odyssey. "We also set the storm jib and reached speeds of five to six knots. What was even better, however, was that the jib made the boat more balanced and the nerve-wracking rolling was finally over after three long days and nights. We literally had the rudder back in our hands."

Then the satellite phone suddenly stops working. As there are no ships within VHF range, contact with the coastguard and the concerned families is lost. When CROSS receives no response to the two-hourly call, another aircraft is sent out. Its crew is asked by the British to pass on a message to the satellite telephone provider. As it turned out, the company had simply cancelled the service due to high usage.

Steering with the emergency rudder system proves to be a difficult learning process in the waves, which are still four metres high. To minimise the rudder pressure, "Quokka" surfs down the waves before the wind. As the boat can easily shift, it demands the utmost concentration from the crew. The helmsman is replaced every 30 minutes, while one person keeps an eye on the rudder and ensures that the fastenings do not come loose. "The ropes and cords that held the whole structure together were constantly coming loose due to the ship's movements. That's why we fitted a tackle on each side so that the system could be easily tightened. Otherwise you would have had to completely loosen the corresponding lines every time," explains Moody.

Across the continental shelf and independently into the box

"Quokka" reaches the notorious continental shelf at night, and as a precaution the crew takes down the headsail to drift rudderless until dawn. When they enter the shallow water, the wind is still blowing at 20 knots, but due to the angle of the waves, the swell is far less dramatic than feared.

At daybreak, the sail goes up again and the boat sets course for Belle-Île-en-Mer. The Breton island is only 40 nautical miles away and the crew's spirits are high, as "Quokka" is expected to reach land before nightfall. In the lee of the island, the sea is calmer, and in the increasingly unlikely event of an emergency, it would only be a stone's throw for the sea rescuers to intervene.

"The last few miles to the mainland went so well that we cockily decided to manoeuvre into the port of La Trinité-sur-Mer without any help. However, our turning circle was so huge that we must have manoeuvred back and forth a dozen times to get into the box," says Rutter. This is because the self-constructed emergency rudder can only be moved about 15 degrees to each side, and the blade is only a third of the normal size, which takes some getting used to, especially in reverse.

But with the mooring manoeuvre, the last challenge is also successful, and the four Brits proudly step onto the jetty afterwards. Ship saved, crew safe and sound - well done!

Lessons learnt by the "Quokka" crew

- You never know when something might break. Our rudder passed the structural tests shortly before we left England.

- Always set sail with sufficient supplies of food, water and fuel.

- A drill in your tool kit is worth its weight in gold. And you can never have enough lines and straps on board.

- An emergency tiller is useless without a rudder. It therefore helps to think about a possible emergency rudder design in advance.

- We had a satellite phone, but our credit was quickly used up - and the provider blocked us! There should always be an emergency number available.

- Some chart plotters display the position of the cursor instead of the position of the vessel. The font size and colour are identical, which can be confusing in a stressful situation.

What to do if you lose your rudder? Four examples

Whether due to orca attacks, collisions with flotsam or simply material fatigue - rudder losses are relatively rare, but all the more serious: if the mast is lost, the only option is to motor to the next harbour. If the engine goes on strike, you can sail. Without a rudder, on the other hand, it becomes much more difficult to get safely ashore. If it is not possible to set up an emergency rudder system, the only option is to tow the boat or, in the worst case, abandon it.

This happened in 2006 with the Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43 "Zouk", which lost its rudder during a transfer voyage to Antigua. The crew fought for the ship for five days. Despite assistance from a tall ship, a robust emergency rudder and an attempt at towing, the crew ultimately had no choice but to abandon the ship. In order not to jeopardise navigation, "Zouk" was deliberately sent to the deep.

Fortunately, there are also encouraging examples of people who have managed to cover large distances or escape from dangerous situations. In addition to the "classic" emergency rudder, there are other possible solutions.

Spinnaker pole as a simple emergency rudder

The Swiss crew of the "Heya" loses their rudder during the ARC 2001. They attach a spinnaker pole to the boat's bathing platform and use two steering lines attached to the pole. With this simple but effective method, she manages to cover the remaining 325 nautical miles to the finish in St Lucia. However, it turns out that the improvised rudder has its limits in stronger winds. In such situations, the crew has to reef early or lean into the wind. A larger rudder blade would have been more effective. Nevertheless, this makeshift solution proves to be sufficient to bring the boat safely to its destination.

X-Rudder: Flexible emergency rudder kit

The kit can be installed on almost any sailing boat. Three special fittings in the yacht's transom serve as anchor points and can be adapted to different hull widths and transom inclinations. Suitable for sailboats from 38 to 48 feet, including a multihull version. According to the manufacturer, installation takes just 7 to 15 minutes. The system is steered via buoys on the rudder head, which are operated directly or via winches, depending on the boat. The system is made of aluminium with a robust rudder blade designed like an aircraft wing. Blades are available in lengths from 1.60 to almost 2 metres. Cost: around 4,000 euros. Click here for more information.

Under sail - but only backwards, please!

A YACHT test showed that sailing yachts cannot be steered in a controlled manner using sails alone - depending on the sail trim, they tend to either turn uncontrolled curls or go into a patent jibe. Nevertheless, there is a way to move the boat to windward in a reasonably safe manner, for example to free yourself from leeward leeches: With the genoa half unfurled and travelling strongly astern, the stern straightens out due to the wind vane effect, while the bow swings strongly. However, this can be minimised by fixing the sheet in the half-wind position, whereby the sail folds over and partially stands back. This allows the boat to move backwards against the wind in slight serpentine lines.

Drift anchor as a manoeuvring aid when towing

In moderate conditions, a drift anchor or a jib with steering lines can help to keep a rough course. Handling is also uncomplicated. However, the boat becomes very slow, which can put a strain on the psyche and supplies over longer distances. If there are no materials for an emergency rudder, towing assistance is often required. It is best to moor the unmanoeuvrable ship alongside, but this does not work in rough seas. For this reason, it is often towed with a long line. However, the damaged vessel must be slowed down by towing objects to prevent it from listing. The drift anchor is ideal for this - at the latest in the narrow harbour entrance.

Morten Strauch

Editor News & Panorama