There are many reasons why the gennaker is increasingly replacing the spinnaker on cruising yachts. For example, the ease of handling. Spinnaker pole, toppnant and downhaul are superfluous - even the barber haul can be dispensed with. You only have to operate two sheets. On very long courses without a planned gybe, you can even dispense with the windward sheet.

Another advantage of the gennaker is its extended range of use. With the early variants, which were a mixture of genoa and spinnaker, sailing on deep courses up to just before the wind was problematic; the bubble was increasingly covered by the mainsail as it dropped and lost its effect. The spinnaker was therefore favoured as it had better all-round characteristics. Modern cuts now allow the gennaker to rotate to windward and thus largely free itself from the cover of the mainsail.

The parts in this sail trim special:

- Trim the mainsail correctly

- Trim the genoa correctly

- Trim the gennaker correctly

- Trimming tips from professional Tim Kröger: Sail settings

No gennaker pole necessary

Therefore, a gennaker pole is not necessary on normal displacement yachts - it is sufficient to attach the neck to a stub spit or the anchor fitting, it just has to remain free of the forestay. Very long gennaker poles, as seen mainly on skiff dinghies or sportier yachts, make little sense on cruising boats. On the other hand, a gennaker pole takes the cloth out of the cover of the mainsail. However, a displacement yacht cannot sail much faster than its theoretical hull speed, the length of its displacement shaft. A larger gennaker would only have the consequence that this "sound barrier" would be reached a little earlier, but not shifted, but handling with a lot of cloth and early pressure would become much more difficult.

Although modern gennakers can be sailed very low, a special sailing technique is recommended when there is little wind: setting out in butterfly mode. Flat in front of the sheet, the gennaker is hauled as far abeam of the boat as possible using a spinnaker pole. As the foot is very long, a telescopic boom is recommended. This means that the mainsail no longer covers the bladder.

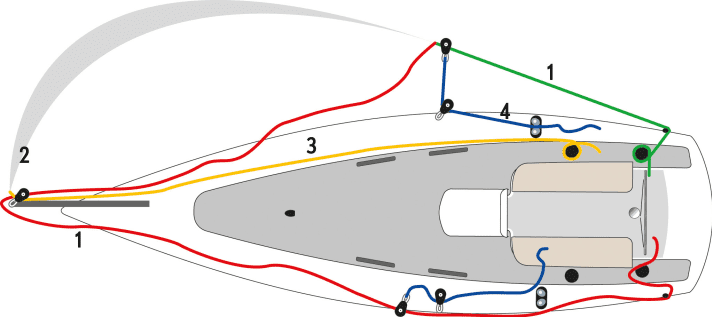

The gennaker components

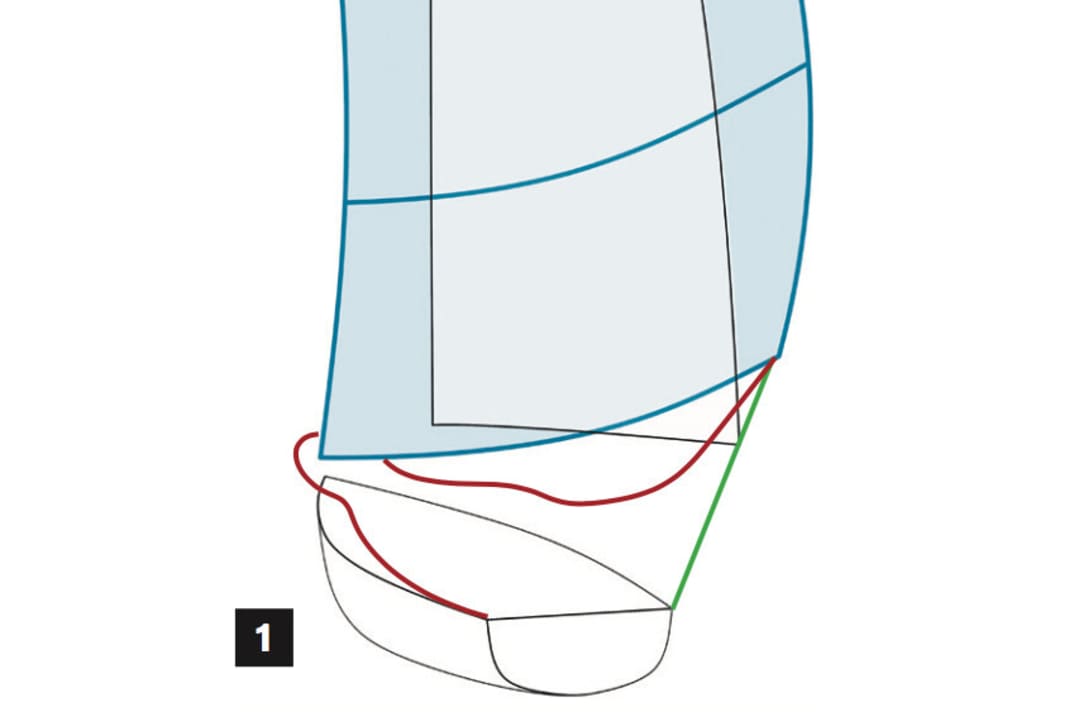

There are two different types of sheeting. On cruising yachts without a long bowsprit, the sheeting has been used on the outside around the forestay. (1) around the boat. When jibing, the gennaker flies around the boat. If a gennaker pole is available, the sail is also jibed between its own luff and the forestay. The cloth can be firmly attached to the bow (2) be used, for example with roller systems, but it is better to use a neck line (3). It enables the gennaker profile to be trimmed and facilitates setting and recovery. Barber furler (4) are not absolutely necessary, but add a component to the trim repertoire. It is best to use snatch blocks on the sheet, as these can be attached and removed quickly. In strong winds, high loads can occur on the barber haul, so it is best to operate this using a winch or tackle.

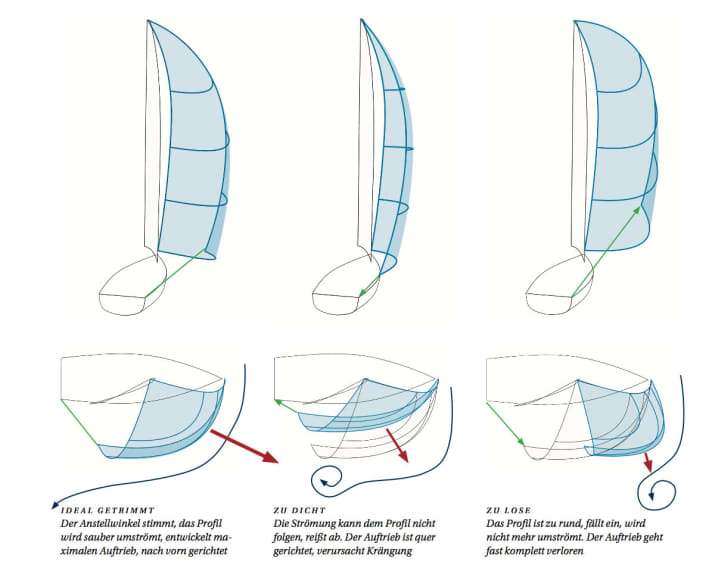

The angle of attack of the gennaker

The sheet is used to regulate the angle of attack and the profile of the gennaker

The correct angle of attack is important, as a gennaker is flown around like a genoa and generates its propulsion through lift, not drag. In order to fill the cloth with wind after setting, the sail is luffed slowly and the sheet is tightened at the same time. As soon as the bladder fills, it must be dropped again and the sheet quickly furled - otherwise the buoyancy will act mainly to leeward, which can lead to strong heeling and a sun shot.

The sheet is furled until the luff of the gennaker starts to kill slightly, turning inwards. The ideal angle of attack is then found, similar to the gently killing windward leech of a genoa. As the outhaul moves forwards and upwards as the sail is fouled, the profile becomes rounder and opens up at the top of the leech, creating the desired shape.

Now the sheet can be actively furled by the trimmer by hand or winch, or passively, by taking up the sheet and the helmsman following the gennaker luff.

Important: Always have the sheet ready for casting off.

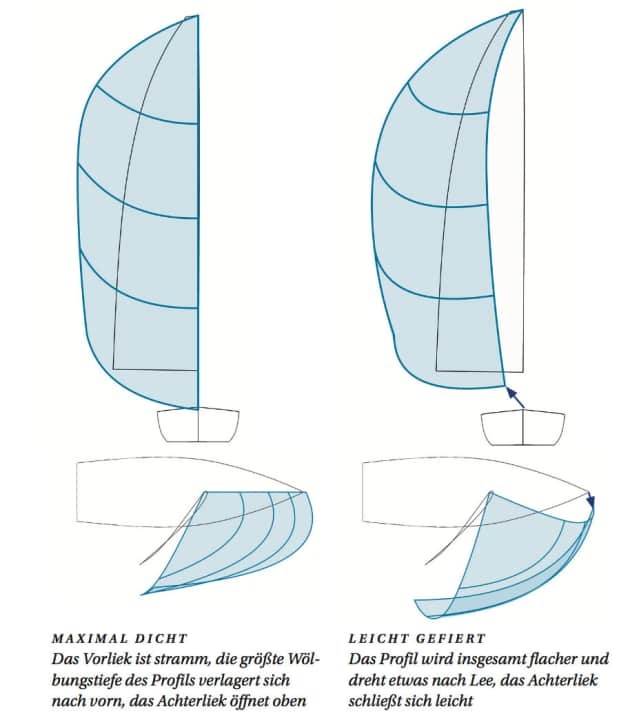

The neck line of the gennaker

With flat-cut gennakers, the profile can be influenced by the luff tension

Older gennakers in particular are often cut in such a way that the luff length corresponds to the distance between the head and tack attachment points. If the halyard and jib line of these sails are fully set, the luff is almost taut. This shifts the luff to windward, and with it the angle of attack becomes more acute. The sail is stretched overall, the width is reduced, the greatest camber depth moves forwards and at the same time the leech opens up in the upper area. The stronger the wind, the more the luff should be stretched. Although some height is lost due to the round profile, this is compensated for by the displacement of the leading edge and the forward-facing lift vector.

If the jib line is feathered a little, the profile compresses and becomes wider, but also flatter. The flat leading edge sometimes allows a little more height in light winds, but with increasing wind the sail moves to leeward and causes heeling.

The drop tension of the gennaker

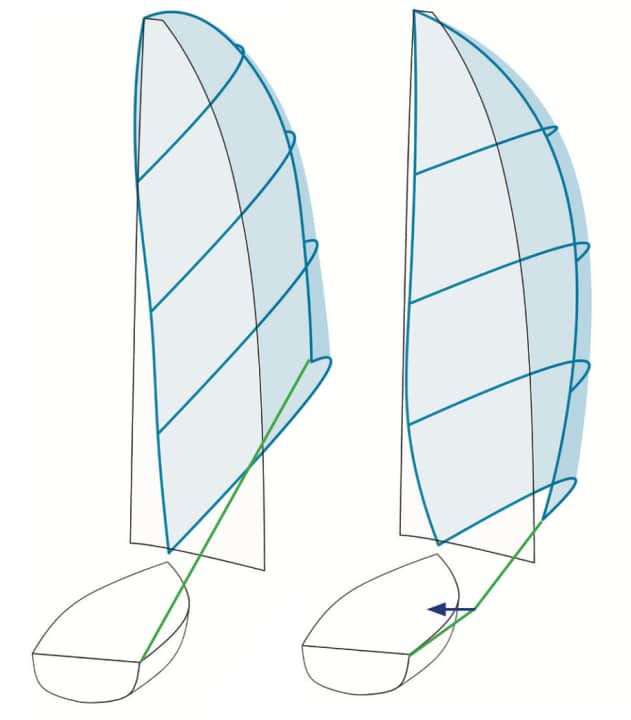

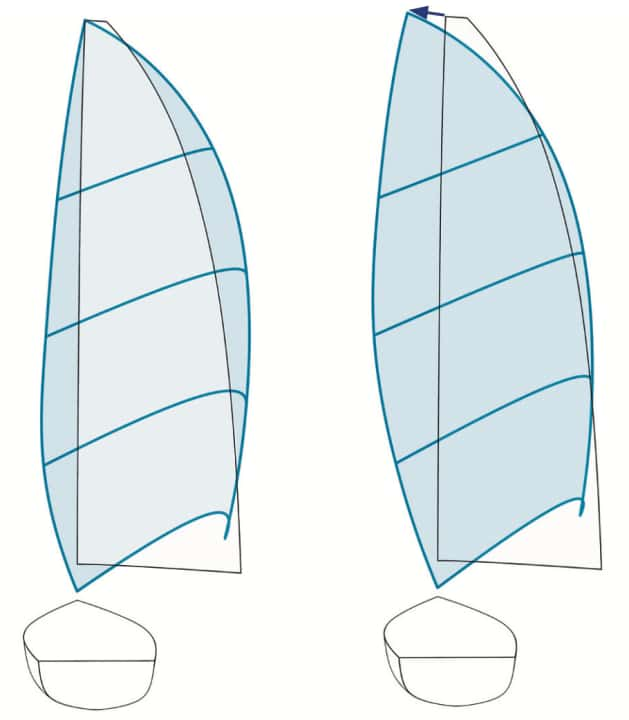

The rotation of the gennaker head to windward can be influenced with the halyard tension

In modern cruising gennakers, the luff is cut about five to eight per cent longer than the maximum dimension between the head and the neck. This means that the luff cannot be pulled taut and some height is lost; only around 80 to 90 degrees to the true wind are possible. On the other hand, the sail is rounder, wider and turns clearly to windward on deep courses, almost like a spinnaker, and the bladder comes more out of the cover of the mainsail. This increases the projected area that is "visible" to the wind, and deep courses of up to 170 degrees wind angle are possible without a boom.

This rotation can be increased by slightly feathering the gennaker halyard. In most cases, a chop of two to three per cent of the luff length is sufficient, i.e. around 50 centimetres at 16 metres. This makes the luff even rounder and allows it to turn even more to windward. However, this also makes the gennaker a little less stable and requires more careful sailing.

The jibe with gennaker

Only two sheets are to be operated, which can also be done single-handedly

When jibing, the gennaker shows its full advantage over the spinnaker in terms of handling. The barber haulers are jibed and can be forgotten for the time being, only the sheets are important. Here, the gybe variant is shown around the outside of the forestay, which makes sense on most cruising boats. It is important that the gennaker is jibed wide and quickly hauled tight on the new side. Otherwise there is a risk of the old sheet falling into the water and getting under the boat.

The only thing that often helps is to unthread the sheet. For this reason, the engine should also be engaged backwards before jibing so that a folding propeller closes securely and a fixed pitch propeller is stationary - otherwise the sheet could wrap around the prop. Gennakers with a furling system or recovery tube can be recovered before jibing in stronger winds and set again on the new bow, which is sometimes less stressful. Finally, the lee barber haul-out can be tightened again.

The furler for the gennaker

The leech of the gennaker can be controlled on deep courses by using the leech

When sailing almost downwind, the sheet must be furled very far to enable the rotation described on the previous page. The tension on the leech decreases due to the increasingly blunt angle, the clew rises, the leech opens strongly at the top and releases pressure. A rounder profile at the top can be achieved by using a leech.

This is a trim line that is attached to the sheet by means of a block or loop and directed aft via a point approximately amidships. A midship cleat is also suitable for this purpose. When set tight, the angle of the sheet pull becomes steeper and the pull on the leech increases. However, inexperienced crews should initially dispense with the barber haul-out, as it must also be furled when luffing. Otherwise it causes a very closed profile and a lot of pressure to leeward.