Man overboard: Get back on board with these tricks and rescue aids

- Rescue only with on-board equipment: What to watch out for

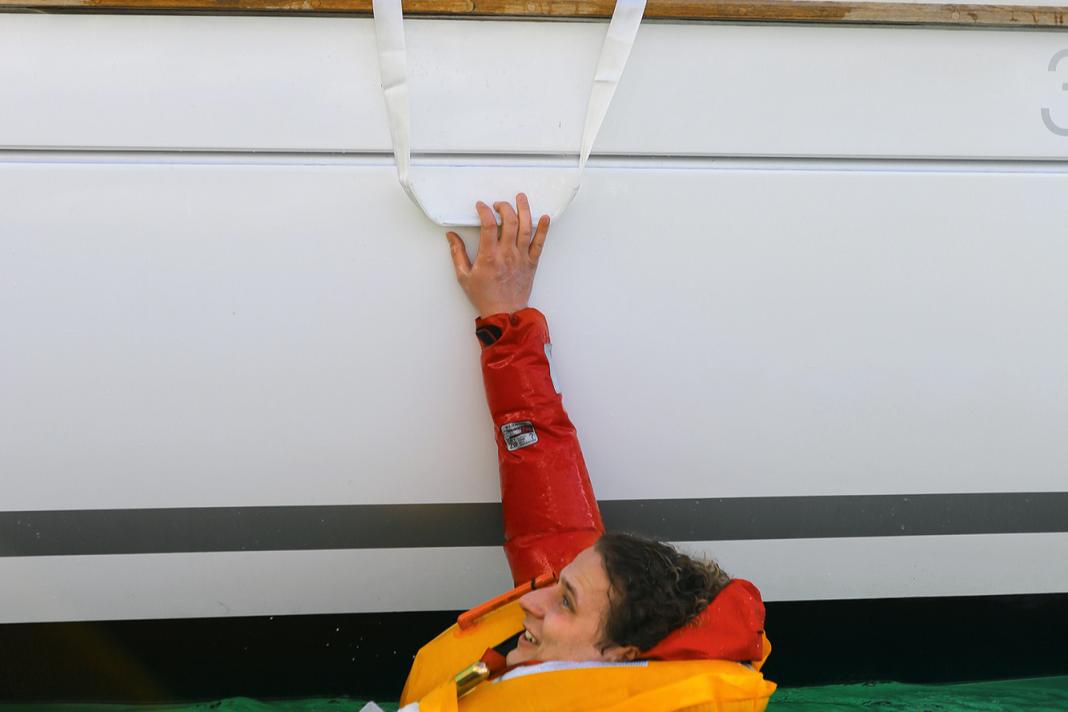

- Recovery sling: How to rescue in an emergency

- Catch and lift: 100 per cent success rate without much effort

- POB-Net: Rescue is simplified, but the person must first reach the ship

- How good are emergency ladders and rescue nets?

All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios

Quickly alerting the crew and locating the person who has gone overboard is one thing, getting the person back to the ship and then back on deck is quite another. Experience shows that even large crews sometimes fail to do this - often with tragic results.

The best way to avoid a mishap is to peg in with a short safety line so that you can't go overboard in the first place. But things often turn out differently than you think, and then an efficient solution is required that can also be operated by the crew remaining on board.

Which brings us to the first challenge, because the crew has to establish a connection to the casualty. The market offers everything from buoys, nets and rescue collars to rescue systems that can pull casualties out of the water almost autonomously.

If there is no recovery system for the man-overboard manoeuvre

However, not all boats are equipped with such rescue aids. On charter boats, for example, there is usually only the prescribed safety equipment such as a lifejacket and lifeline. And the situation is often no different on private sailing yachts.

After a successful MOB manoeuvre In this case, it is also important to establish a connection between the boat and the casualty. A line is thrown for this purpose. In the simplest case, the person still has strength so that they can be led to the stern with the line and can then be lowered over the swim ladder on their own. If the sea is too rough and the stern is pitching, or if the person in the water is too weak, only a rescue ladder amidships or winching up will help.

Once the halyard is hooked into the lift loop on the casualty's lifejacket, he has to be winched up. This is extremely strenuous! Halyard winches are usually smaller than those for genoa sheets. In addition, the halyard may get jammed between the pulley on the masthead and the sheave box as it is pulled very far to the side.

Rescue only with on-board equipment: What to watch out for

To avoid this and to make winching itself easier, a block and a mooring line or a fore sheet can help. The block is attached to the halyard and the genoa sheet or mooring line is threaded through it. One end is attached to the winch, the other is used to pick up the person. If a mooring line is used, it must also be threaded through the hollow point so that the angle of pull to the winch is correct. In this way, the genoa winch can be used for hauling up.

What many people don't realise is that the person has to be winched up so far that they can get over the railing. However, there is a risk that the person will sway strongly when the ship moves and hit the shrouds, mast or main boom. This becomes even more of a problem if the person is recovered horizontally. In this case, fellow sailors on the running deck are enormously helpful, guiding the casualty while he is still suspended in the air.

It is also possible to rescue a person from the water single-handed, we tried it out. However, this requires a lot of practice beforehand. An electric winch simplifies the process enormously, especially if it can also be operated from the steering wheel. Nevertheless, experience shows that rescuing a crew member who has fallen overboard quickly becomes a challenge, even with a crew. Especially when improvisation is required.

Rescue with recovery systems

If you can fall back on rescue aids and other rescue systems, throwing lines or rescue loops are a good option. These are towed on a line about 30 to 40 metres long. If you circle the person in the water, the collar describes a narrower radius than the yacht, which means that the casualty will sooner or later get hold of the line or collar.

Once a line connection has been established between the boat and the person in the water, it must be pulled back to the ship. The quality of the floating line is crucial for this: it is usually pulled in hand over hand. This can generate considerable forces when hauling it in. In our practical test, the yacht drifted to leeward in 16 to 18 knots of wind at just under two knots, significantly faster than the person in the water.

Recovery sling: How to rescue in an emergency

In rough seas, the pull on the rope continues to rise, at least temporarily. The classic two-man crews should then be able to fall back on the genoa winch. Hard, smooth and even too thin ropes are a problem, as they may get caught in the selftailer of the winch.

The next step separates the wheat from the chaff. The wet, possibly exhausted and hypothermic person has to be brought on deck. In full gear and with plenty of water in the oilskin, the subject weighs well over 100 kilograms. Lucky if you have an electric winch on board. However, you have to improvise to use it, as there is no hoisting eye accessible from the deck on all recovery slings. Instead, the halyard has to be attached using a knot. An unnecessary fiddle that delays the recovery process.

Catch and lift: 100 per cent success rate without much effort

Martin Schührer from MS-Safety had these problems and an imminent long journey in mind when developing the recovery system called Catch and Lift.

Schührer and his sister benefited from their experience as parachutists and manufacturers of medical and military equipment. Instead of a strong crew or winches, the design relies on a special brake parachute and machine power.

The idea is as simple as it is captivating: in an emergency, a line connection to the casualty is established using a throw line and rescue loop, as with conventional rescue loops. It runs over a deflection block that is attached to the upper shroud. Its end is not permanently attached to the boat, but is connected to the brake parachute.

Catch and Lift gets the person out of the water and onto the ship

If the line connection is successful, the parachute is deployed and the yacht continues its journey. The parachute acts as a drift anchor and generates so much resistance that the person is pulled towards the yacht and lifted out of the water - without the rescuer having to get off the helm. In our practical test, Catch and Lift impressed with its ease of use and 100 per cent success rate for rescues, see YACHT 20/2016.

The person who has gone overboard only needs to be circled around and not approached directly, which prevents them from going overboard when there are a lot of waves. However, if they are no longer able to hook on, it becomes difficult. If the crew is strong enough, someone can go into the water and pick themselves and the casualty; the glider will then pull them both on board. Otherwise, a classic MOB manoeuvre with hooking in from the bathing platform will be necessary. Martin Schührer refutes the objection that the rescue is not carried out in the horizontal position by pointing to the speed of the manoeuvre. This means that the crew member is quickly back on board and does not suffer from hypothermia.

POB-Net: Rescue is simplified, but the person must first reach the ship

The POB-Net currently offers the best chances of a horizontal rescue, see YACHT 24/2020. It is a rescue net that can be deployed quickly and is also designed to get a completely immobile person out of the water horizontally. And it can even be used by just one crew member. The net is stowed in a round bag measuring 70 centimetres and is hooked onto the railing using a carabiner, after which the cover is opened. The recovery net unfolds automatically, similar to a throw tent. This is what the construction looks like, only with a net instead of a tent canvas.

As soon as the casualty is in the POB net, the second carabiner is hooked into the main halyard and the first is clipped to the shroud so that the person overboard in the net does not swing uncontrollably against the ship's side. If the net with the person is above railing height, the person is pulled inwards over the running deck. In the test, it worked well to simply turn the net around the upper shroud. However, it did not stay in this position. It could be secured towards the kicker with a Zeiser so that the rescuer could go aft to the winch again to carefully lower the rescued sailor on deck.

The POB-Net worked surprisingly well in our test. Before the procedure described, the boat must of course be steered right next to the person in the water. Compared to classic rescue nets or a converted storm jib, the POB-Net is immediately ready for use and is easier to manoeuvre under the casualty.

How good are emergency ladders and rescue nets?

As long as the person can still help, the bathing ladder is the usual means of re-entry; no other rescue aids are required. However, this is often not accessible from the water on current yacht models with a wide stern and large bathing platform.

Special rope ladders promise a solution, see YACHT 20/2016. The ladders are stowed in a bag on the railing and can be released from the water by pulling a handle in an emergency. They are better than nothing, but they cannot compete with a classic, permanently mounted swim ladder with wooden rungs at the stern.

Rescue net: longer set-up times, also acts as a ladder

Video test of recovery aids at YACHT tv:

All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios