The mainsails of yachts do not have to be triangular. More and more sails can be seen that are flared in the top area. They are called squareheads or fatheads and can be seen on almost all modern high-tech yachts, such as the Imocas in the Ocean Race or the Vendée Globe. Almost all pure racing yachts use them, such as the 100-foot "Comanche" as the largest or the Mini 6.50 class as the smallest; many sports boats come with squareheads, as do modern sports catamarans, dinghies and foiling speedsters. Even wing systems, such as on the current America's Cup boats, are wide and square at the top.

There is a reason for this: a squarehead mainsail offers decisive advantages over a pinhead, i.e. a mainsail with a triangular top section.

Also interesting:

Nevertheless, the sails with the powerful heads are subject to many prejudices. Because of the larger sail area at the top, it is said that the sail's centre of pressure would also move upwards, which would increase the heel on upwind courses and lead to more upwind yaw. Such sails would only be suitable for light winds and would have to be reefed early.

The opposite is the case. In fact, up to 30 per cent more sail area can be achieved in the main with a wide leech. It is logical that this brings enormous advantages on room sheet and downwind courses. The more the principle of propulsion by lift, as when sailing downwind, is replaced by the principle of propulsion by resistance, as on deep courses, the better it is to offer the wind as much surface area as possible for high resistance. Or to put it simply: a lot of surface against which it can push and thus take the yacht with it.

More effective inflow with the Squarehead

But even on upwind courses, flared sails have clear advantages. The decisive factor is the ratio of lift to drag. The greater the lift of a sail and the lower its drag, the greater the propulsion. This ratio is extremely poor with conventional triangular sails.

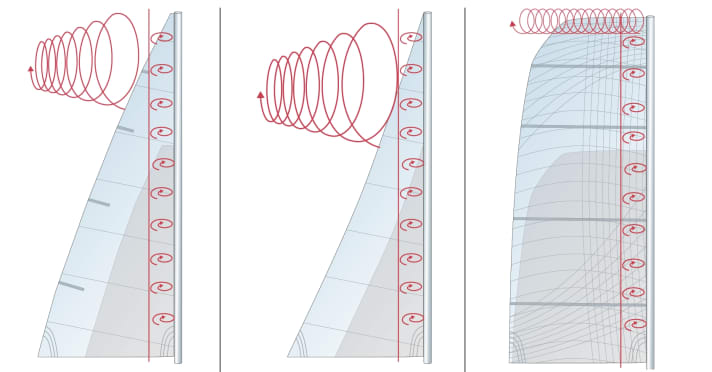

The mast profile in front of the sail creates turbulence. Depending on the profile thickness and shape, these can extend 30 to 40 centimetres, sometimes even up to 70 centimetres, behind the mast. In this area, a vortex zone forms that hardly provides any lift. Only after this does the current attach itself to the cloth again - if there is any. This is because triangular-cut mainsails rarely have a correspondingly large profile length in the top area, i.e. the distance between the luff and leech. Before the current can make contact, the sail is finished, so it only creates resistance.

Measurements have shown that up to 18 per cent of the sail height measured from the top can be ineffective and only cause drag. In tests, even this upper part was cut off, leaving only the luff and leech lines for stabilisation - the sail was not slower.

This phenomenon is exacerbated when reefing. This is because not only the absolute sail area is reduced, but above all the effective sail area. This is because the ineffective cloth remains in the top area, while the effective cloth is tied away at the bottom.

This effect can be minimised with a wide opening in the top area. The current finds enough cloth to be able to reef. Reefing also only reduces the sail area, but the effectiveness of the sail is retained.

The squarehead is actually horizontal

Squarehead sails are most effective when the top section is actually horizontal and not in the shape of an ellipse. For a long time, this was considered the ideal, like the wing of a Spitfire fighter from the Second World War. The hard edge at the top of a squarehead sail should therefore actually favour induction vortices, i.e. pressure equalisation between windward and leeward, similar to that at the bottom around the main boom. This would act as a brake.

But this effect does not materialise. This is due to the dynamic behaviour of such sails. In a gust, the top of the sail opens faster than with other sail shapes. In addition, the free vortices in a square top sail flow away aft more favourably than in an elliptical outline. In this case, the free vortices on the leech shimmy downwards a little from the top. As a result, the sail with a flared, elliptically rounded leech loses some of its so-called effective span. The hard edge acts as a kind of vortex brake.

More sail, less pressure thanks to Squarehead

However, a squarehead sail not only generates more propulsion, it can even reduce heeling and rudder pressure and shift the reefing point to a higher wind speed range. Because the entire cloth works effectively, the sailmaker has the option of cutting the profile flatter overall than with a conventional sail. This means that the sail's centre of pressure does not move any higher. In addition, a flatter sail allows a more acute angle of attack, i.e. more height upwind. The flatter profile also generates less drag.

With increasing wind, such a sail can be twisted much better in the top area than a triangular one. The sail cloth that is not needed is virtually placed in the wind, but does not kill because it is supported by battens and the stiff laminate used.

In the most favourable case, the so-called inverted twist even occurs. The upper two to three battens fold to windward, the sail then generates lift to windward in the upper area and thus a righting moment. Although inverted twist is also possible with conventional sails and has been practised for some time, it requires one or two continuous battens at the top and is not as effective as with a squarehead mainsail.

Attentive trim on the Squarehead

However, a wide flared mainsail must be trimmed much more sensitively than a conventional mainsail. The twist is crucial. If the leech is closed too much, the pressure point moves upwards and the squarehead will heel a lot and generate less propulsion. The same applies to pinhead sails, but trimming does not have such a strong effect. That's why a squarehead mainsail is sailed slightly differently, with the main boom more amidships and almost no downhaul, even in stronger winds. This requires a sheet car that can be hauled to windward. In a gust, the sheet should be furled first. This causes the main boom to rise and the sail can twist away at the top.

With a pinhead sail, on the other hand, the sheet car tends to be feathered to leeward in order to change the angle of attack of the more effective lower section. However, these are very rough trimming formulas; the fine adjustment depends heavily on the respective configuration.

Fun brake backstay

The reason why the squarehead main is not used more often in cruising sails is simply because of the backstay - it limits the leech of the mainsail. Although modern pinhead sails are also already well rounded and the leech protrudes slightly above the backstay, they too are a long way from a true squarehead. This is only possible with backstayless rigs, as on many smaller sports boats, or on larger boats when backstays are used.

However, cruising sailors with conventional rigs can at least achieve an approximation. Even a small boom on the masthead of 15 or 20 centimetres in length, plus a slightly lower sail head, allow a noticeable extension of the top range. However, this requires modifications to the rig. If you shy away from this, you will end up with a less effective sail.