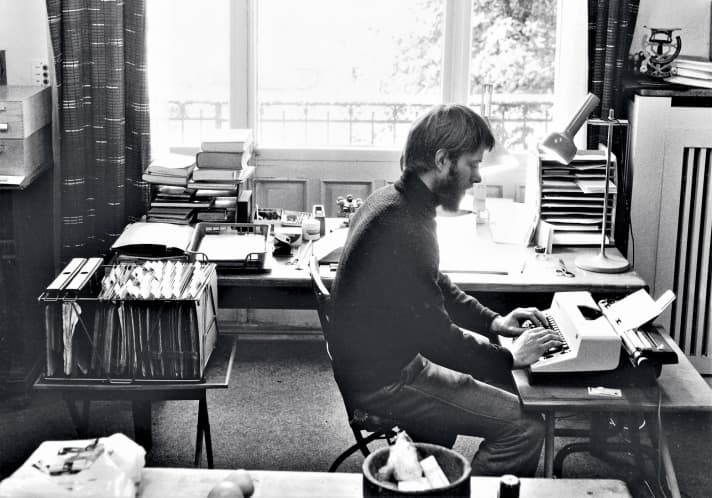

A study not far from the Elbe. A 75-year-old gentleman sits at a desk, steel rivets lie in front of him, behind him hang construction plans of four-masted barques, books are piled up everywhere: ship inventories, nautical encyclopaedias, treatises on barges and old cargo ships.

The man doesn't even have to give his name. Joachim Kaiser is known far beyond his own neighbourhood as the saviour of the "Peking". And many other ships. As the "Ewer Pope", as he was once called in the Hamburg press. This is where the father of various associations for the preservation of old boats and co-initiator of the Hamburg Maritime Foundation sits. The grand seigneur of German traditional shipping.

And anyone sitting opposite him will inevitably ask themselves a question after a while that has not yet been scientifically researched. Can the penchant for historic ships be anchored in our genetic make-up? Kaiser ponders this question for a moment, then says: "I don't know where I got it from, it certainly didn't run in the family. Nobody in our family used to have the slightest interest in ships."

Joachim Kaiser looks back on an incredible biography

So there he was, in Hamburg, an up-and-coming city after the war, a rather mediocre student, his mother a music teacher, his father a professor of zoology. His brothers, uncles, neighbours: nobody was interested in the sea or sailing. This makes the biography that Joachim Kaiser looks back on today all the more incredible.

Ships, ships, ships. And what does looking back mean? Plans of a famous square-rigged sailing ship are currently on his desk. Kaiser is writing an expert report, has to assess the condition of the huge ship and record its details. Then there is his own boat, a 7-KR mahogany yacht built in 1967 by Matthiessen & Paulsen in Arnis. He wants to take it up to Norway again this summer.

The rescue of the "Peking"

Its largest and probably best-known salvage object is located in Hamburg today. A landmark of the city, a 106 metre long tourist attraction that once sailed the seas with 62 metre high masts and 34 sails: the steel four-masted barque "Peking", built in 1911 by Blohm + Voss in Hamburg. The proud windjammer had been languishing as a museum ship in New York since 1974 - bringing it back to Germany over forty years later was basically a crazy idea.

For Joachim Kaiser, however, the story of the "Peking" had begun much earlier. In the early seventies, he had seen a silent film about the ship: "The Peking Battles Cape Horn".

Kaiser was still a greenhorn at the time, but was all the more impressed by the imposing ship - and the man who presented the film in Hamburg's Überseeclub: Irving Johnson. The American had the crazy idea of buying the "Peking", which was laid up in England at the time, rebuilding it and exhibiting it on the pier of the South Street Seaport Museum in front of the Manhattan skyline. In 1976, Kaiser was one of the first visitors to marvel at the freshly rigged ship.

The film about the "Peking" spurs Kaiser on to carry on

A good 30 years later, however, the museum was bankrupt. A fateful question arose: what to do with the dilapidated windjammer? Dispose of it? Scrapping it? For Kaiser, it was an almost unbearable thought.

For the Hamburg Maritime Foundation, which was established in 2001, he inspected the famous Flying P-Liner, which once circumnavigated Cape Horn 34 times. In 2008, he crawled through the hull of the huge ship, inspected its interior and saw massive damage.

The "Peking" was a wreck, and Kaiser was horrified. If he hadn't still had that early black and white film in his head, he would have aborted the tour. But the dramatic scenes that showed the four-masted barque at her wedding played in his mind's eye. The "Peking" in a storm, surrounded by wild seas. And he carried on.

Now a member of the foundation's board, Kaiser nevertheless warned at home against the audacious idea of bringing the "Peking" back to Hamburg. Without a two-digit million sum, he was convinced, it would ruin the foundation.

The restoration of the "Bleichen" as a model for the "Peking"

Meanwhile, the company acquired the Hamburg general cargo freighter "Bleichen". Almost as large as the "Peking", the ship was technically even more complicated. Highly motivated volunteers came together, ABM workers, sponsors and craftsmen. The team gritted their teeth on the restoration for almost ten years. But in 2015, the 95-metre-long ship - perfectly restored - was actually put back into service. Whereupon Kaiser retired after a nerve-wracking few years to finally go sailing.

He thought. But a year later, the foundation was asked to restore the "Peking" under his direction. The federal government, sponsors, curators and cultural authorities had been keeping a close eye on the "Bleichen" project and the majority decided in favour: If the "Peking" is to be retrieved and saved, it should be by these guys.

Kaiser struggled. He knew what was in store for him and everyone else. But the scenes from the film replayed in his mind again. Until he finally said: "Well then, let's get on with it!"

Without Irving Johnson and his film, the 'Peking' would most likely not have survived"

With his experienced team, Kaiser took on what he soberly describes as "project management". In the end, the endeavour took five years and cost almost 40 million euros. Today, the "Peking" is not only a piece of German maritime history, but also a jewel of the harbour. But Kaiser is certain: "Without Irving Johnson and his film, the 'Peking' would most likely not have survived."

Joachim Kaiser brought old ships back to life for 40 years

The "Peking" is ultimately just the tip of the iceberg. Joachim Kaiser can now look back on over 40 years of finding, assessing and restoring old ships. For complex operations, he often co-operated with experts and shipyard specialists and called in boat builders and craftsmen.

But he was usually the one pulling the strings. Like a conductor in front of whose podium old ships are brought to life. Floating cultural assets that were scattered around the world and that Joachim Kaiser has brought back together to form a visible maritime heritage of Germany - together with many companions, as he emphasises. With young people, boat builders and supporters of all kinds who got involved and were passionate about the boats.

The list of all these ships is long. It fills entire books dealing with the history and details of the old vehicles. It all started back in 1974, when the Hamburg native was involved in the restoration of historic ships. For four years, the "Johanna von Neumühlen", a 64-tonne cargo ewer with a wooden floor, built in 1903 by Jos. Thormählen in Elmshorn, was refurbished. Joachim Kaiser took over the construction supervision and personally took care of the forging work and the construction of the centreboards.

How Joachim Kaiser became the "Ewer Pope"

Without pausing for breath, he embarked on his next project, the "Herrmann von Wewelsfleth". The last surviving wooden cargo ship, built in 1905 at Carsten Witt's shipyard in Wewelsfleth, was a sad wreck. Kaiser discovered the battered ship in Amsterdam, the local heritage organisation for the Steinburg district acquired it and Kaiser transferred it back to the Elbe as a deck cargo. This was followed by measurements, reconstruction drawings and construction supervision.

And so it went on, ship by ship. Deep-sea fishing cutters, herring luggers, steel sea-going ewers, cargo schooners, twin-screw steamers and wooden customs cruisers - historic working ships of all categories are what Kaiser saved from drifting into oblivion.

In the early years, he also worked as an editor at YACHT, and his first book was published in 1974: "Segler im Gezeitenstrom - Die Biographie der hölzernen Ewer". Writing and ships were a fruitful combination for him. Research, maritime fieldwork and meticulous descriptions went hand in hand and were a symbiosis for everyone involved. The first book became a rare reference work, complete with coloured pen and ink drawings and meticulously researched details of the boats.

The most important book was a register of the stock of German sailing ships

A traditional ship scene was just beginning to form when Kaiser published his first works. And yet there were many readers who shared his soft spot for old ships even then. His most important work, he says today, is the booklet "Deutsche Segelschiffe - Register über den Restbestand 1980 bis 1986". In order to be able to carry out the meticulous work and publish the book, he received support from the Krupp Foundation and its sailing-enthusiast Chairman Berthold Beitz. Kaiser had endeavoured to obtain external funding for the first time. He eventually received 20,000 marks - and experienced first-hand the cultural significance that historical boats could have.

At the time, however, nobody realised how much work was involved in tracking down the threatened ships all over the world. There were no emails and no internet. Kaiser wrote hundreds of letters, made phone calls, travelled, sneaked through shipyards and archives, chugged along lonely river arms. Boats were his life, theoretically and practically. Of course, there were also the restoration projects, which often took years, and on top of that he wrote about ships, about seafaring, about captains.

Kaiser sits somewhat pensively in his study as he revisits all those years in his mind's eye. "It was madness," he says today. "The term burnout didn't exist back then, but I think I was close to it sometimes."

A maritime Sisyphean task

In a biographical flashback, he describes his maritime Sisyphean task as follows: "Many of the hulls still in existence in the 1970s were barely recognisable as sailing vessels, they were either sailing as converted coasters and inland waterway vessels or eking out an existence as trailers and houseboats. My self-appointed task was to inventory these historical objects, regardless of where and in what condition they were, and then to publish a register of them. This task grew into a project of considerable proportions, involving long journeys and international correspondence."

So nobody is talking about a hobby. Ships have always been a passion for Joachim Kaiser. A profession and a vocation at the same time. And in the years that followed, he not only had two daughters and, in the meantime, grandchildren: the boats also got bigger and bigger. In order to save the characteristic sailing ships of the Elbe in particular, Kaiser initially gathered the "Friends of the Gaff Rig" around him, a group of "alternatives and non-conformists" who had set their minds on preserving not churches, windmills or old farmhouses, but ships as a cultural asset.

Harbour cranes, bridges, quay sheds: Kaiser restored everything

Kaiser, however, led the ships to other tasks. And later supervised major historical projects of a completely different calibre. He restored harbour cranes and riveted arched bridges, and during his work for the Hamburg Maritime Foundation he also took on the task of restoring the 50s quay sheds in the free port. A generational project: some of the historic warehouses and office buildings for general cargo handling were in danger of collapsing - frighteningly large wooden buildings from the last century with an area of 35,000 square metres.

But the buildings smelled strangely of seafaring, of overseas spices. That irresistible odour that only maritime trouvailles from days gone by can exude. The sheds also include the show depot of the harbour museum, in which over 10,000 objects are exhibited on the subjects of port work, cargo handling, shipbuilding and revierschifffahrt. Today, however, the Hamburg Maritime Foundation primarily owns 14 preserved boats, which can be marvelled at in various traditional harbours.

The "Undine of Hamburg" and its utilisation stand out

If you ask Joachim Kaiser about an outstanding ship, about a very special experience in all those ship-filled years, he mentions a special project: the "Undine von Hamburg", a steel cargo motor schooner built in 1931 at the Niestern Bros. shipyard in Delfzijl in the Netherlands. Kaiser and his wife at the time bought the dilapidated ship with their own funds. No small feat: the freighter was measured at 96 tonnes GT and could carry 70 tonnes of cargo. Kaiser took over the reconstruction drawings and the entire project management: shipbuilding, blacksmithing, carpentry and rigging work were all carried out in-house.

After the ship had been approved by Germanischer Lloyd and the See-Berufsgenossenschaft and classified as the only commercial sailing cargo ship flying the German flag, Kaiser had something very special in mind: From then on, young people from difficult backgrounds were to sail on the "Undine" in order to give these unfortunates a new perspective.

Social work at sea on the "Undine"

Social work at sea. And there was a need. In the meantime, the 1980s had dawned. In order to be able to offer such youth work, Kaiser founded the Hamburg-based "Gangway e. V.", under whose aegis the old two-masted schooner transported cargo across half of Europe for two decades.

Each voyage lasted six months. On board: four pedagogically trained sailors and employees as well as eight young people who travelled as deckhands and received full basic maritime training en route. The old ship was to pave the way for them into working life. Kaiser himself sailed on the "Undine" as captain for seven years; he had already acquired the necessary licence beforehand. "That time shaped me," he says. "God knows it wasn't always easy, but it was what my heart beat for."

A person can hardly do more for seafaring

Kaiser's CV reads like proof of what can be done with ships, especially sailing ships, if you have enough kinetic energy. The ships that owe their survival to Joachim Kaiser have served as educational centres and social safety nets, carried freight, sailed the seas and still adorn various museum harbours today. Windjammers like the "Peking" attract tens of thousands of visitors every year and have become as much a part of Hamburg's cityscape as fish on a fish sandwich. In other words: a person can hardly do more for seafaring.

The Hamburg Maritime Foundation appointed Kaiser as an honorary board member and the Senate of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg awarded him the Biermann-Ratjen Medal for his cultural services. And yet one question remains unanswered: Where does his enormous enthusiasm for the ships come from? Where did this tic that became his life's purpose come from?

Gorch Fock and his own little ship turn Kaiser into a sailor

Kaiser gets up, goes up the stairs, comes down again. He is holding a small red book in his hands. When you open it, you can see the coat of arms of Hamburg, next to it a proud five-master sailing across the sea under full sail, drawn by hand. Above it is written in spidery letters: "Segelschiffahrt - Joachim Kaiser".

The book is a kind of compendium of his early dreams, dating back to 1958, when he was just eleven years old. He had carefully glued photos of famous sailing ships into the book back then, the "Pamir", the "Passat" - as well as photos of his first own boat: the "Woterküken". A tiny bent spanker with a plug-in mast and lateen sail, which he had talked a friend into buying.

"A totally rudimentary youth boat," recalls Kaiser, who also had other things in his early marching luggage: books. He devoured Gorch Fock's "Seefahrt ist not!", Count Luckner's "Seeteufel" and the "Großes Buch der Seefahrt".

Secretly onto the Elbe

This sparked his longing. The boy wanted to go to sea, wanted to sail, wanted adventure - even if his family looked at him uncomprehendingly. His mother and father had other plans for their son. He was actually supposed to become a teacher.

At the age of 13, he sailed on the Alster, travelling up the Alster to the Isebek and Eilbek canals in his "Woterküken". Sometimes he would take down the sail and punt the boat through the narrow waterways "like a raftsman". Instead of doing his schoolwork, he sewed sails, built a cockpit into the boat and a launching board.

One day he was given an engine, a 2.5 hp König petrol engine as a sideboard. The boat was now more manoeuvrable, more agile even in adverse wind conditions and currents. And despite all his promises to his father not to venture onto larger waters, he did just that: the little Kaiser grabbed a tide table and Elbe atlas and was soon sailing out onto the river. Upper Elbe, Lower Elbe, with the tide through the Customs Canal. He had a tent with him, a spirit cooker, ravioli and a paraffin lamp he had borrowed from a building site.

Joachim Kaiser had his own adventure

During these years, he had his own adventure. It was the early sixties and the waters in northern Germany were still reasonably wild and free. Kaiser was a Huckleberry Finn of the Elbe. He pulled his flat-bottomed boat onto the reed banks, slept on the deserted Elbe islands, sailed into muddy harbours, collected amber on the Brammerbank and dozed in the sand next to his little boat. "The thing was just three metres long, but I did a lot with it back then," recalls Kaiser.

Over sixty years later, he sits in his study as if it was all just yesterday. His first boat trips, his early excursions on his own. His course to his own freedom. "The boat brought me up, it was like an early maturing process. I was responsible for the 'Woterküken' - and for myself."

When the father found out one day that his son had sailed out onto the Lower Elbe after all, there was a lot of trouble. And a strict sailing ban. Well, as we know, it didn't help. The father should have known. You can ban the boy from the boat, but you can't ban the boat from the boy.

And Joachim Kaiser is one of them. He has ships in his blood.