"And once again I would like to urgently warn against travelling the sea in a folding boat." Hannes Lindemann, born on 28 December 1922, ended the book about his Atlantic passage in a folding boat with this surprising statement. With a warning that obviously did not apply to him.

On 20 October 1954, he circumnavigated Gran Canaria's harbour pier at the northern tip of the island by rifle light. A quiet start, stealing away, "nobody should be worried," he confessed in a WDR interview in 2012. Besides, many people thought his plan was a bit, well, bizarre anyway. He could probably do without the farewell from the numerous sceptics.

At first, he is unable to set off before sunrise because he is looking for the urgently needed sextant, which is eventually found under the seat. Finally cast off, a boat hurries to him on behalf of the harbour commander, telling him to come back immediately and clear out. In the process, the barge overflows the retrofitted port float, consisting of half the tube of a car tyre, fixed with a paddle that breaks during this manoeuvre. Gritting his teeth, the small boat adventurer turns round.

Cruising in a dugout canoe was a luxury compared to a folding boat

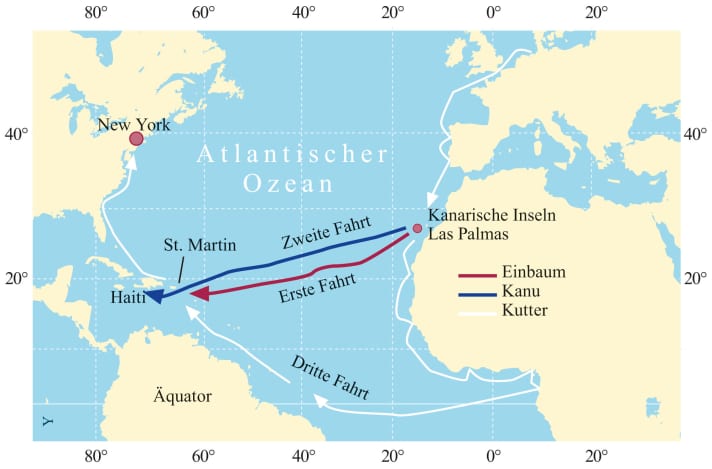

But this would be his third time turning back. He had already dared to take the plunge twice before coming ashore again. The season before, he had sailed the same route from the Canary Islands to the Caribbean in a dugout canoe. A journey full of privation. He had experimented with drinking seawater and suffered greatly.

And yet he considers his dugout canoe trip to be a luxury cruise compared to his current endeavour. Hannes Lindemann is driven not only to show himself, but also the world, and in particular this French dazzler, the incroyably successful and revered doctor Alain Bombard. Two years earlier, he had also set off from the Canary Islands in a rubber dinghy and drifted across the Atlantic as a castaway. When he arrived, he proclaimed, contrary to previous knowledge, to drink salt water for weeks on end: it works.

This was doubted by Hannes Lindemann and others who claimed to have seen Bombard hiding a hundred litres of drinking water in his dinghy. They argued that he had fed himself princely on steamers crossing his course. But still, Alain Bombard had endured this endless loneliness admirably. And his fame! Hannes Lindemann already has expertise, and he is also a doctor. And he feels so ready for this unique folding boat trip.

72 cans of beer as a source of calories

Because whenever he drank a lot of seawater in the dugout canoe, he suffered from oedema; if he drank fresh water, it receded. What the Frenchman was saying was rubbish! He wanted to prove it with his folding boat trip. This time he set off with three litres of water. What madness. Well, there are also 72 cans of beer on board, more as a calorie supplier. He wants to use rainwater and the liquid from squeezed fish to avoid dying of thirst in the middle of the sea or from the consequences of drinking salty water. Hannes Lindemann turned round once again that morning, heading west.

After 72 days, Lindemann reached Philipsburg on the Caribbean island of St Martin. Emaciated by 25 kilograms, but otherwise mentally and physically intact. The successful crossing was initially a wave of success. The hardships, the trepidation after capsizing at night on the 56th day, the even smaller diet because a number of provisions were lost in the process - they were worth it.

It is now nine o'clock in the morning; I write in my logbook: "The ordeal begins"

Extensive folding boat tours were gaining huge popularity in Germany at the time. The successful history of this type of boat began on 30 May 1905, a particularly warm day on which architecture student Alfred Heurich set up his "Luftikus" on the banks of the Isar, a completely new type of four-and-a-half metre-long vessel at the time, in which the scaffolding and planking were almost brazenly separated. Inspired by Inuit kayaks, the frames, which are held in position with bamboo poles, are simply covered with canvas. Alfred Heurich reaches Munich, 50 kilometres away, in five hours. In 1907, the folding boat inventor sold the licence for series production to the sporting goods dealer Johann Klepper, who gave his name to the shipyard that still produces Lindemann's "Aerius II" model today, albeit with various improvements.

Pioneers in a folding boat

Hannes Lindemann is not the first long-distance traveller in a folding boat, but he is still the most famous. In 1930, Oskar Speck paddled and sailed down the Danube in a folding boat from the "Pionier" shipyard in Bad Tölz, crossed the Mediterranean eastwards, circumnavigated India and worked his way along the coasts of South-East Asia to Australia, which he reached in 1936. Two years before Oskar Speck, Captain Franz Romer from Litzelstetten near Constance embarked on the first folding boat journey across the Atlantic. He lands in the Virgin Islands after 58 days. After a stopover on Puerto Rico, the boat and crew disappear without a trace.

What Lindemann had not railed about Captain Romer's folding boat. In fact, his windy vessel was a custom-built one. Klepper-Werke had built him a six-and-a-half metre long boat with a freeboard of forty centimetres and a width of one metre according to his plans. It was still daring to set sail in the fragile kayak, but it was no longer a standard boat. In contrast, Lindemann had bought his even smaller "Aerius II" from a sports shop - sponsorship was still extremely rare in those days. Nevertheless, he upgraded his folding boat for the trip.

The boat moans and groans in every sea as if it were my own bones"

None of this was to be seen in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, where it had been on display for decades. In a letter to Günter Hennemann, a former supervisor at the Deutsches Museum, Lindemann writes: "The fact that old Mr Klepper neatly removed my numerous modifications to the folding boat can probably be described as a falsification." For example, there was a "second skin for the deck", more likely a spraydeck up to the aft mast, an upright paddle. And further: "I had attached thin elasticated boards from an orange crate to the coaming, on which two waterproof rubberised equipment bags were placed to soften the force of breakers." He had also left the backrest at home, as he didn't want it to be too comfortable to make it easier to stay awake.

The folding boat in the Deutsches Museum

Hannes Lindemann's kayak is only admirable in context. It was exhibited in the Deutsches Museum between an even older folding boat and racing rowing boats, almost incidental. Without the sextant, watches, compass, waterproof torches and underwater rifle. Externally, the hulls of the rowing boats and the folding boat are similar, but it is the Atlantic crossing that makes "Liberia III" something special.

Nevertheless, her journey to the museum was a long one. "I kept having guided tours where there were questions specifically about the folding boat," says museum supervisor Günter Hennemann, "then in 2005 there was a report in YACHT about Lindemann, and I asked the people in charge at the museum whether we should get in touch with him." They were sceptical at first, "but after an initial exchange of letters, he invited me to Bad Godesberg". "Would you also be interested in showing my folding boat with equipment?" Hannes Lindemann asked Günter Hennemann, enviously pointing out the "Tilikum", a small boat that was on display as an attraction at Canada's National Maritime Museum on Vancouver Island. "Since my trip with the series folding boat is still an absolute world record, it should be possible to achieve something similar in Germany." He reminded Günter Hennemann: "The biggest magazine in the world at the time, 'Life', featured the crossing in a cover story. An honour that was only bestowed on one other German: The other was Adenauer."

It is rumoured that the editor-in-chief of the magazine with an international reputation tried to prove that the Atlantic crossing was faked. He ordered a Klepper boat and tried it out in his swimming pool. "He got in, tipped out on the other side and then declared the journey impossible," Dirk Richardt wrote in an article for the Deutsches Museum. Only the steamship sightings saved Hannes Lindemann from being seen as a fraud. The publication then worked. In the "Life" cover photo from 22 July 1957, a burly Atlantic conqueror laughs from the folding boat. Compared to the North American enthusiasm, the reception in Germany was "undercooled, perhaps we Germans are simply not a seafaring people".

Günter Hennemann asked whether Lindemann had not been memorialised anywhere. There is a "Dr Lindemann Street" on Heligoland, he replied mischievously. However, it turns out that it is dedicated to Dr Emil Lindemann, who was a spa doctor there from 1984 to 1892. A sports hall and Kapitän-Romer-Straße in Dettingen are named after Captain Romer. An honour that Hannes Lindemann would have wished for?

Hannes Lindemann was a YACHT author for many years. His articles include "Folding boats and canoes don't belong at sea". Together with his partner Ilse and "Liberia IV", an almost nine-metre-long cutter of the "Colin Archer" type, he wanted to sail around the world, but ended up with an Atlantic passage.

Lindemann's autogenic training became standard

Hannes Lindemann disproved Alain Bombard's dubious saltwater tips with his folding boat trip. Autogenic training for shipwreck was even recognised as a standard procedure by the World Health Organisation. Hannes Lindemann had optimised self-suggestion for the passage in a collapsible boat. "I can do it! Course west! Don't give up! Don't accept any help!" were his famous guiding phrases, which he internalised and which actually gave him a mental framework when the folding boat capsized, his already decimated supplies sank and he had to swim alongside the boat until the morning to right the boat again in the light of day - it could have turned out very differently with or without the guiding phrases. After all, the three kilometres of swimming every day as preparation had been worth it.

However, the recognition of autogenic training had a flaw. Hannes Lindemann's method was sponsored by Johannes Heinrich Schultz. The psychiatrist is regarded as the founder of autogenic training and was a specialist until the 1970s. But J. H. Schultz was also deputy director of the "Institute for Psychological Research and Psychotherapy" of the notorious "Göhring Institute". He propagated the "extermination" of disabled people so that "the idiot institutions will soon empty". Lindemann is not known to have publicly distanced himself from his mentor.

Lindemann became a role model for Wilfried Erdmann

Hannes Lindemann became a role model for many, especially in the years after the successful passage, explicitly for Wilfried Erdmann: "He set me on the right path with information." "I admired him, admired him endlessly," says circumnavigator Rollo Gebhard. He bought the Klepper Aerius as his first boat out of enthusiasm and sailed on Bavarian lakes. The most important thing he learnt from "Alone across the Ocean" was that Hannes Lindemann did everything right, "but you can't really do that with a folding boat". How true: German Tim Weltermann sets off from Gran Canaria on 25 October 2003 to cross the Atlantic in a kayak. A yacht crew spotted him on 31 October, but nobody else did after that.

WDR reporter Marko Rössler asked Lindemann on his ninetieth birthday whether he could not have made his attempts on land? Why, he knew he could do it. "The hardships weren't that great for me. For others yes, I believed in the boss up there."

The hull, i.e. the thin planking of a folding boat, makes seafaring particularly immediate. Over the years, the doctor and adventurer appears reconciled to the great fame - which failed to materialise. The skin, the membrane to the beyond, seemed to become softer. To the boat again? "You want me to go to Munich again? Nope." Not even to the sea. Hannes Lindemann was approaching the end of his cruise at the age of ninety - "not bad, not bad, not at all". Hans-Günther "Hannes" Lindemann died on 17 April 2015. "He has set off on his last voyage," read his obituary.

Three journeys, three experiences

In 1955, Hannes Lindemann started out with a hollowed-out and largely covered tree trunk 7.80 metres long and 76 centimetres wide - which is more like a diameter, the 600 kilogramme displacing "Liberia II" must have been enormously slender. "Liberia I", eleven metres long, had burnt down while the African boat builders were "smoking out" the wooden trestles. The passage with the dugout canoe to Tahiti took 65 days. He tried his hand at savouring salt water, as Alain Bombard had been propagating since his dinghy passage in 1952. And discovers considerable discrepancies. In 1956, with his own findings and Hannes Lindemann as his test subject, he made the legendary crossing of the Atlantic in a folding boat, and four years later he did it again in the 8.98 metre long Colin Archer construction "Liberia IV"

Technical data "Liberia III"

- Model: Klepper "Aerius II"

- Total length: 5,20 m

- Width: 0,78 m

- Depth:0,27 m

- Displacement: 27 kg

- Foresail/mainsail:1,35/3,4 m²

- Inflatable air hoses:80 l

- Construction method: Wooden frames and stringers, covered with Hypalon