Drive: What you should look out for when manoeuvring with an electric motor in the harbour

Alexander Worms

· 02.08.2023

The yacht glides silently into the harbour. No clouds of smoke, no splashing of cooling water. Then an audible gurgle from the propeller well, and the boat is already stationary. Accurate to the centimetre. The secret to this precision is the ship's electric drive. Because it is simply a poem when manoeuvring in harbours. But why is that?

Firstly, let's take a look at the diesel: it has an idling speed of around 700 revolutions per minute. With a gearbox reduction of two to one, this means that the propeller completes at least 350 revolutions as soon as you engage the gear. Less is not possible. It is therefore a constant trade-off between thrust and no thrust. Very little thrust is not possible.

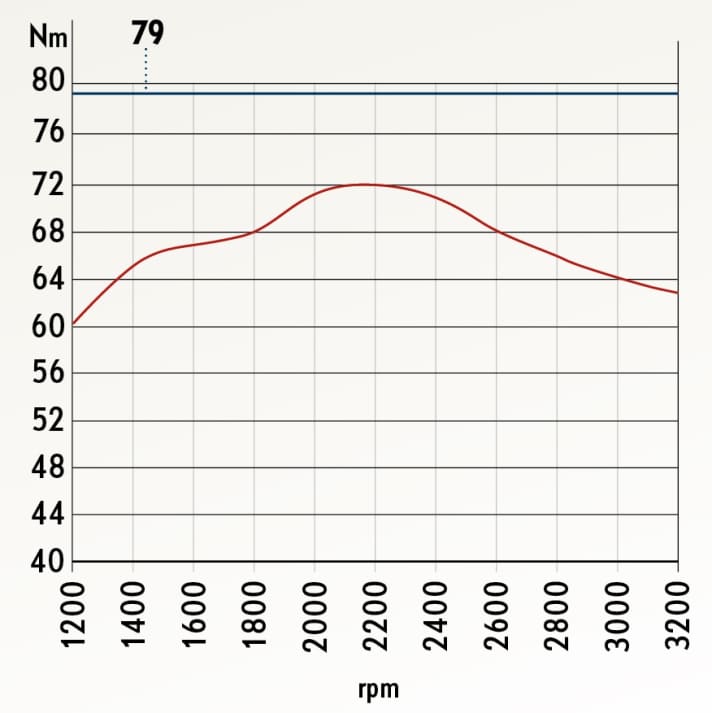

And then, for example when stopping, more power is required. However, the diesel only has this at higher engine speeds. A 30 hp diesel reaches its maximum torque at around 2,200 revolutions per minute. But that's pretty strong for harbour manoeuvres. So the helmsman has to shift gears with foresight and work on the throttle.

The electric motor has full torque immediately

The electric motor, on the other hand, always has the same power available from the first revolution. Its torque is constant. This means that the motor can be perfectly controlled and manoeuvres can be performed with pinpoint accuracy. However, as with the diesel, you need to be sensitive to the usually small control lever.

The enormous torque ensures good acceleration ahead and quick stopping astern, which can take some getting used to at first. However, the propeller must be precisely matched to the drive and the boat, which is important when replacing an old diesel with an electric drive, for example.

Keyword replacement: If you are also secretly thinking about purchasing a bow thruster, the electric drive can also be a solution by simply installing two smaller motors instead of one larger one. These are then installed as so-called pods, i.e. small drive nacelles, under the hull, each off-centre. This gives you the option of two engines when manoeuvring, allowing the yacht to turn on the spot. Bow thrusters? Superfluous!

Torque curve

Energy management for the electric motor

The e-drive is also slightly different when travelling on the road. You will automatically always be mindful of a range-optimised driving style. It helps to keep a close eye on speed and energy consumption and to experiment with this.

As the energy requirement increases exponentially, even small reductions in speed are very good for the range. So instead of travelling at 5.0 knots, perhaps only 4.5 knots ultimately means a disproportionately greater range. It is important to keep this in mind. Thanks to the reserve, a one-third/two-thirds rule for the outward and return journey ensures a good feeling if there is more wind on the nose than expected on the way home.

What many owners who have switched to an electric drive also report is that they are sailing much more again. Situations in which you could sail safely but shy away from the short cross for reasons of comfort, or you would rather motor through the doldrums than wait for the wind a day later so as not to waste a day's holiday, are more often decided in favour of wind propulsion with an e-drive. And that in itself is a good thing.