- Only what is measured is done

- Technological approaches

- Everything that can be electrified will be electrified

- Drop-in fuels - the mirage of decarbonisation

- E-methanol with better availability

- Electrification and the role of hydrofoils

- Decarbonisation as an upgrade - not a sacrifice

- Pioneer for electromobility

Text by Christoph Ballin

When we sit in our cars and drive across the country or through the cities, electric cars are already an integral part of road transport. The global share of battery electric vehicles in new registrations has risen to 14 per cent in recent years. A key driver of this rapid development is the general consensus that the decarbonisation of road transport will be achieved through electrification.

On the water, however, progress is lagging well behind. It is estimated that the proportion of boats with electric drives is far below two per cent and is currently only increasing slowly. What is even more worrying is that there is still no clear idea of how climate-friendly mobility on the water is to be realised.

More on the topic:

A small boat consumes around ten times as much energy as a car of a similar size at normal gliding speed. We therefore cannot simply copy what is becoming increasingly popular in cars for boats and yachts.

At the same time, yachting will lose its lustre and desirability if our industry falls further and further behind in the transformation towards more sustainability - there are fewer and fewer people who doubt this. It is therefore time for us to define how the transformation as a whole is to succeed.

Only what is measured is done

It is generally recognised that under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, a total of 197 countries agreed to limit global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius, or alternatively less than 2 degrees Celsius, compared to the pre-industrial era. The agreement stipulates that climate emissions should be reduced by 45 per cent by 2030 compared to 2008.

What is less well known is that the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is guided by this reduction and has derived its own target for international shipping from it. According to this, climate-damaging emissions are to be reduced by 20 to 30 per cent by 2030. With an acceleration in the following years.

There is no official target for the maritime leisure industry. No data on the development of climate emissions is collected or published either. We have to assume that Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG) are not going down, but actually up: The number of yachts has grown significantly in recent years, while at the same time the engines are becoming more and more powerful.

The boat and yacht industry should therefore set itself targets as quickly as possible on how and how quickly it can become more climate-friendly. The IMO's reduction targets would be a good point of reference for the speed of transformation. A common understanding of which technologies should be used to tackle decarbonisation is needed as a basis.

Technological approaches

Basically, there are four main technologies available to us for decarbonising boats and yachts.

- Electrification, i.e. switching to battery electric vehicles, so-called BEVs

- Hydrogen can be used in two ways for climate-friendly drives: firstly, with fuel cells that feed electric drives. Secondly, as a fuel for combustion engines. In the second case, considerable modifications to combustion engines are necessary

- E-fuels such as e-methanol or e-ammonia can be used just like hydrogen in fuel cells or combustion engines. Modifications to the combustion engines are also necessary here

- E-fuels that can be used in existing engines without modification are known as drop-in fuels, for example e-diesel, e-gasoline and hydrotreated vegetable oils, or HVO for short

If you look at the alternatives mentioned above, it quickly becomes clear which of the new drive technologies have a good chance of making progress in the short term and becoming established in the long term.

Everything that can be electrified will be electrified

Battery-electric solutions are gaining ground in many mobility segments because they are by far the most efficient overall. Climate-friendly electricity can be used in vehicles, including yachts, without additional transformations. In comparison, all drive concepts that rely on multiple energy conversions are significantly less efficient.

For example, if a vehicle is powered by hydrogen and a fuel cell, electricity is first converted into hydrogen and then converted back into electricity in the fuel cell. This process requires three times as much energy as a battery-electric solution. That means three times as many wind turbines and three times as many solar fields.

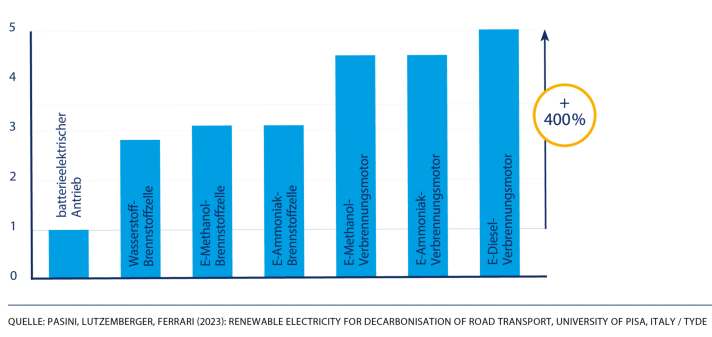

If e-methanol or e-ammonia is used in combustion engines (see diagram), four times as many wind turbines and solar panels are required for the same amount of propulsion. Drop-in fuels even require five times as much energy as battery electric drives.

We have to assume that climate-friendly energy will remain scarce in the coming decades - until, for example, nuclear fusion is available or climate-friendly energy is sufficiently available by other means. As long as this is the case, overall efficiency will be a key factor in determining which drive technology will prevail. In view of the clear superiority of battery-electric solutions, it is therefore to be expected that everything that can be electrified will also be electrified on the water.

Drop-in fuels - the mirage of decarbonisation

In November last year, a large-scale study by ICOMIA - the international association of the maritime leisure industry - presented drop-in fuels as the preferred path to decarbonisation. For almost all boat types analysed by ICOMIA - superyachts were not considered - drop-in fuels were the supposedly best technology for powering yachts in a climate-friendly way in the future. The problem with the study is not that drop-in fuels are a bad solution per se. Above all, they would be a very convenient solution for the industry because nothing would have to be changed to the existing engines and because there would be no conversion problems during the transition phase.

The problem is that drop-in fuels will not be available in relevant quantities for boats and yachts for the next ten to 20 years.

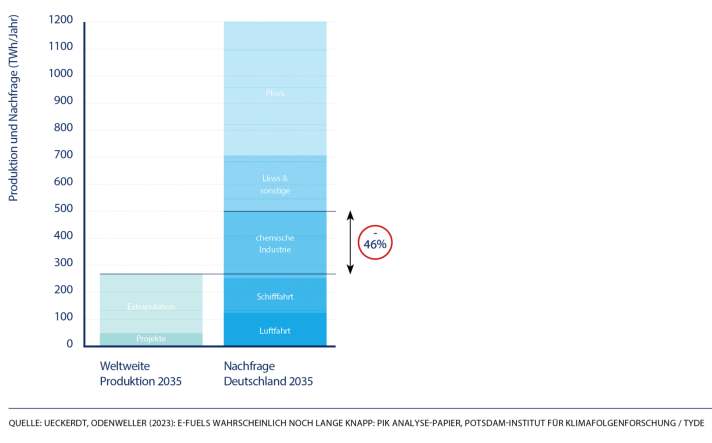

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research once compared the predicted global production of drop-in fuels in 2035 with Germany's demand alone (see chart). The result: global production will cover around half of German demand in 2035. This is true even under optimistic assumptions - including that cars and lorries will not use drop-in fuels at all and will therefore not compete for the scarce production with other essential industries such as the chemical industry.

If we rely on the use of drop-in fuels for boats and yachts, this means that there will be no decarbonisation in our industry for the next ten to 20 years. This would be a total loss for the social acceptance of boats and yachts.

E-methanol with better availability

E-methanol is more likely to be a suitable fuel for climate-friendly mobility: conventionally produced methanol is one of the world's most widely produced chemical raw materials. Methanol can be stored and transported using known technologies and infrastructures. In addition, methanol can be used in both combustion engines and fuel cells.

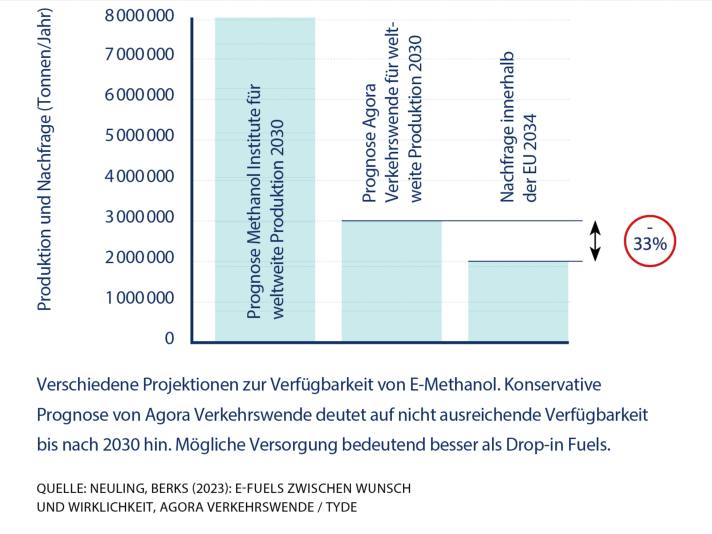

For use in combustion engines, e-methanol requires comparatively minor changes in engine technology, including in engine management and injection systems. However, the climate-neutral production of e-methanol must be carried out using green hydrogen and CO2 and requires a lot of energy. In comparison, however, production is simpler than the production of drop-in fuels. It is to be expected that e-methanol will be available in larger volumes more quickly. This means that e-methanol can make a faster contribution to the decarbonisation of mobility on water. Engine manufacturers and superyacht shipyards are working on pilot projects and series solutions for ships powered by e-methanol. The disadvantages of e-methanol remain its high energy consumption, especially when used in combustion engines, and the fact that e-methanol will still be in short supply in the coming years.

Electrification and the role of hydrofoils

The electrification of mobility on the water began almost 20 years ago. Torqeedo was the first company in the world to set itself the goal of replacing combustion engines with electric drives in certain applications.

Due to the high energy requirements for propulsion systems on water and the limited energy density of batteries, electrification has so far been limited to a few segments: Applications with low power, low speed, short range, applications on standard routes. Real progress is being made in these segments. However, these niches are not very large.

At the same time, spectacular progress has been made in sailing racing with hydrofoils. Hydrofoils reduce the required propulsion energy by up to 80 per cent because they minimise the friction of the hull and do not use energy to build up stern shafts weighing several tonnes. Over the past ten years, foiling has also changed from an art to a science.

For fast motorboats and yachts, electric drives with hydrofoils are by far the most climate-friendly technology available today:

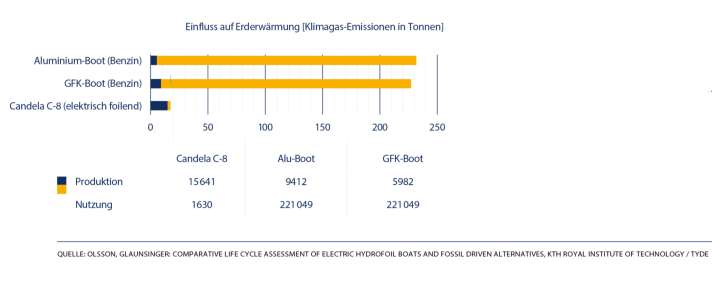

- At higher speeds, electric boats with hydrofoils require significantly less energy than conventional boats

- Thanks to their low energy consumption, foiling boats can manage with smaller battery banks. This also makes their production comparatively climate-friendly

Another special feature of using hydrofoils is that they not only make yachts more climate-friendly: Travelling on hydrofoils is much more comfortable and elegant than with conventional hulls: there are no bumps, no rolling, nobody gets seasick. This aspect is important for the spread of climate-friendly mobility, as environmentally friendly mobility is most successful when it is not perceived as a sacrifice.

In addition to the development of hydrofoils, battery technology will also make great progress in the next three to five years. It can be assumed that conventional electric yachts will achieve ranges of

50 nautical miles at cruising speed. The most comfortable and climate-friendly way to cover distances of over 100 nautical miles will be with foiling electric yachts.

Decarbonisation as an upgrade - not a sacrifice

The combustion engine has always had the advantage that it can cover the requirements of all applications: all outputs, all ranges, all speeds.

Climate-friendly mobility will require different solutions for different applications. Battery electric drives are entering the market "from below", so to speak - starting with small, slow boats and moving towards ever larger and faster formats. E-methanol drives, on the other hand, are entering the market first from large yachts, "from the top" so to speak.

The good news is that with the combination of e-methanol and electrification, all segments of the yachting industry can be decarbonised. Where the boundary between the two technologies will run is the interesting question.

One influencing factor will be that the performance and price-performance ratio of electric drives will continue to improve over the next few years. Conversely, the price-performance ratio for combustion engines is expected to deteriorate as the large volumes of the automotive industry move away from combustion engines.

Will there be a third technology in the middle between these two technologies, such as hydrogen propulsion? A healthy scepticism may be allowed here, as it will hardly be worthwhile to support three infrastructures for energy supply and drive technology in the rather small yacht industry. In addition, the requirements for a hydrogen infrastructure are difficult.

What the transformation needs, however, is cooperation between manufacturers and owners. It is the task of manufacturers to offer fascinating and attractive climate-friendly products so that the switch to future-oriented drives is an upgrade and not a sacrifice. At the same time, it remains a challenge for manufacturers to drive forward the industrialisation of the new drives in order to reduce the price premium that is currently still necessary for sustainable drives.

This also requires innovative yacht owners who want to be pioneers for new, luxurious and clean mobility on the water and who, as customers, support manufacturers in the industrialisation of new technologies.

Pioneer for electromobility

If the former McKinsey consultant Christoph Ballin had not become managing director of garden tool manufacturer Gardena in the course of his career, there would be fewer electric drives on the water today.

Together with Gardena's Chief Technology Officer Friedrich Böbel, he founded the pioneer and market leader for electric drives, Torqeedo, in 2005.

15 years later, after the purchase of Torqeedo by Deutz, Ballin left the company he had founded, but remained true to his goal of making mobility on the water more sustainable. In 2021, he founded the Starnberg shipyard TYDE with his partner Tobias Hoffritz.

Ballin is also on the advisory board of the Austrian start-up SEA.AI, which specialises in artificial intelligence for recognising objects on the water.