Soft rigging is not a new trend, Dyneema rope shackles have long since found their way onto almost every regatta and cruising yacht, and textile aft stays are also widely used, at least on performance cruisers. However, the potential applications of Dyneema fibres are far from exhausted. Dyneema, or rather high-modulus polyethylene (HMPE), has almost ideal properties for use on board. The fibres offer wire-like low elongation, enormous tensile strength and are also UV and seawater resistant. Thanks to their smooth, soapy surface, they are abrasion-resistant and generate little friction.

Also interesting:

The material is also relatively easy to splice, especially if it is treated with a polyurethane coating. This coating not only serves to colour the inherently white fibres, it also bonds the fine filaments into compact carding ropes, which means that the rope hardly pulls any threads and can also be used as a single braid without a cover. For example, in the form of a lashing as a replacement for shroud tensioners to push through the railing or as a flexible coupling between the backstay and tensioner. The advantages of the textile solution are that it is not only lightweight and corrosion-resistant, but can also be made quickly and has a practically unlimited tensioning range. The only thing to ensure is that the lashing does not run through sharp-edged fittings or eyes.

The safest option is to use round thimbles. The smooth surface protects the cordage and ensures that the load is evenly distributed over the strands and that the lashing can be pushed through easily.

We were shown how modern lashing is done by rigging professional Max Kohlhoff from the outfitter of the same name in Altenholz near Kiel. The company not only has a rigging workshop for wire and rod stays, but is also Germany's top address for textile rigging. Company founder Peter Kohlhoff was also a pioneer in metal-free connection technology on board with his version of the rope shackle called a loop shackle.

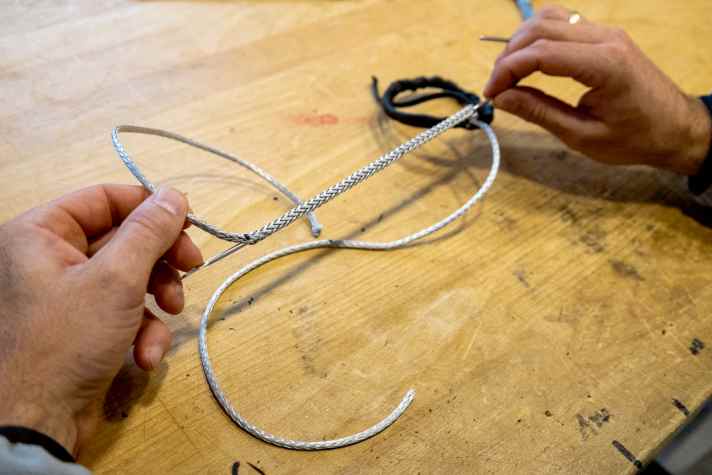

As mentioned at the beginning, practical shackles are now widely used. Endless slings or loops are much less common.

They are suitable as an elegant and high-strength connection, for example for attaching blocks or round thimbles, or can be used as a shackle together with a toggle called a dogbone.

Working on the sling is not difficult

The simplest variant is an endless spliced ring made of Dyneema. However, only very large loops can be produced in this way, as the length of the endless splice depends on the diameter of the cordage used. To create sufficient friction and ensure that the splice holds, the length should be 50 to 100 times the diameter.

A loop of five millimetre thick cordage must therefore be spliced together to at least 25 centimetres. This means that in practice it can hardly be smaller than 30 centimetres. It is more favourable to use two or three strands with a diameter of three millimetres instead of a single five-millimetre loop. As the force is distributed over the strands, the splice is less stressed. In addition, the loop can be pulled apart during splicing. This allows sufficient splice length to be achieved without the finished loop having to be larger.

A sheath is also used to keep the strands in position. Side effect: The sheath protects the loop from abrasion, which means that it not only offers a higher breaking load than a shackle, but is also significantly more robust.

Making such cover loops is not difficult and does not require any special tools. In fact, the diamond knot required for rope shackles is more complicated to tie than the work on the loop, but there are considerably more steps involved. It is also more difficult to splice loops of the same size. If you want to make a series, you should make a template. For example, a board with two nails at the distance of the desired loop length. The splice length and taper should also be measured precisely, as they also influence the length of the finished loop. The thin sheath braid made of Dyneema is only available from specialised rope dealers. However, it can be used for a whole range of cordage diameters, and a few metres in stock on board won't do any harm.

Real breaking load

Loops are always used where particularly high loads have to be handled. Theoretically, the durability of the sling is determined by the breaking load of the core material used and the number of strands. When properly spliced, even the connection of the core should have almost the same breaking load as the pure cordage. The cover plays no role in this consideration. It basically only serves as mechanical protection and to hold the strands together. Our loop with a three-millimetre core and four strands should therefore be able to withstand around 6000 decanewtons. In the test, it broke at just over 5000 decanewtons. This is a considerable value compared to a rope shackle made of the same material. The shackle broke at the knot at around 3000 decanewtons. A shackle spliced from sheathing braid broke at the eye at 2200 decanewtons.

Step by step to the lashing: A tensioner made of cordage

Thin Dyneema braiding is best suited. The thinner the material, the more wraps are required.

1. attachment to the eye

The single braid is attached to one eye. The end only carries a small part of the load later, so a bowline is sufficient. An eye splice is more elegant.

2. threading

Thread so that the parteners are next to each other and do not cross over. Reach into the parteners in between to distribute the tension evenly.

3. wrapping

The number of wraps depends on the breaking load of the stay. The loose end is guided between the strands as the end ...

4. conclusion

... and threaded in figure eights around the strands. After at least four loops, form a half-loop around one of the strands.

5. fuse

To prevent the half hitch from coming loose, place a figure eight knot behind it to secure it. Alternatively, two half hitches can be made.

6. reworking

The finished lashing. Melt off the excess material behind the figure of eight knot. It can then be slid between the parteners.

Step by step to the loop: A high-strength connection

The endless sling with sheath requires many work steps. However, it is robust and has an enormously high breaking load.

1. determine size

Determine the size of the loop and cut the sheath about 15 centimetres longer. The diameter of the Dyneema braid depends on the core, with ...

2. preliminary work

... two strands with a thickness of three millimetres must fit inside. Also roughly cut the core to length. Around 60 centimetres extra are needed for splicing.

3. surfacing

The sheathing braid should be upturned about 15 centimetres from one end. It will later be spliced into a ring at this point.

4. start of splicing

Insert the splicing needle into the sheath from the long end and allow it to emerge at the compressed position. Thread on the core ...

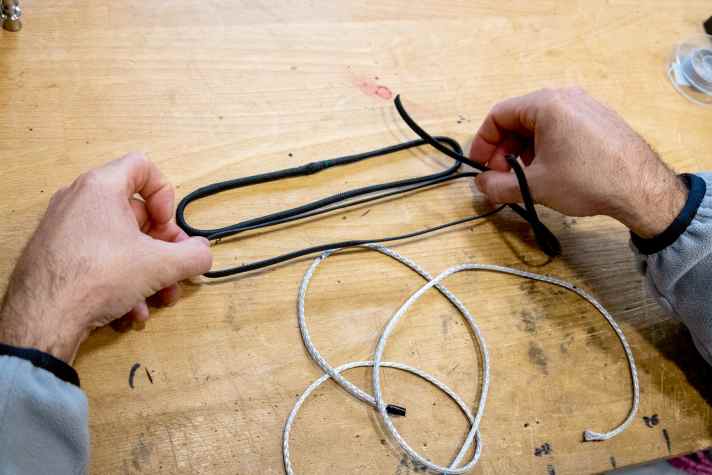

5. pull in the core

... and pull it into the coat. Only a short piece needs to stick out. Everything is then placed in a ring and the end of the core is pulled out before ...

6. threading aid

... glued into the casing on the core. The tape should form a cone. Slide the core in a circle so that the double strand slips into the sheath.

7. mark position

Remove the tape and milk the casing smooth on the core loops until two ends of the same length protrude. Mark the crossing on the core.

8. connect core

To connect the core with an endless splice, pull on both ends until enough material is exposed. This pulls the first loop together.

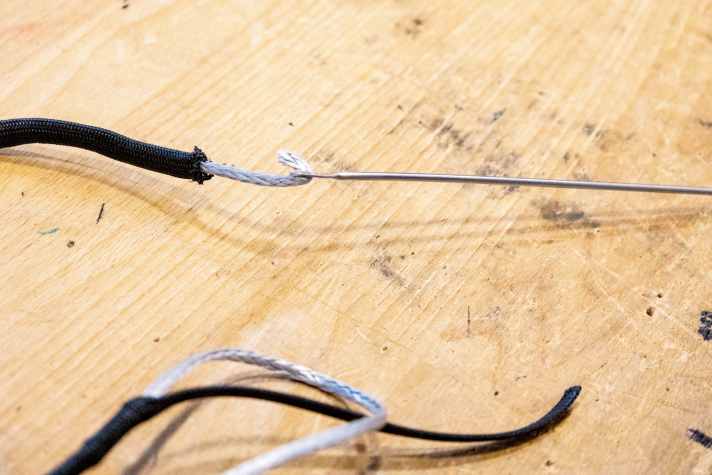

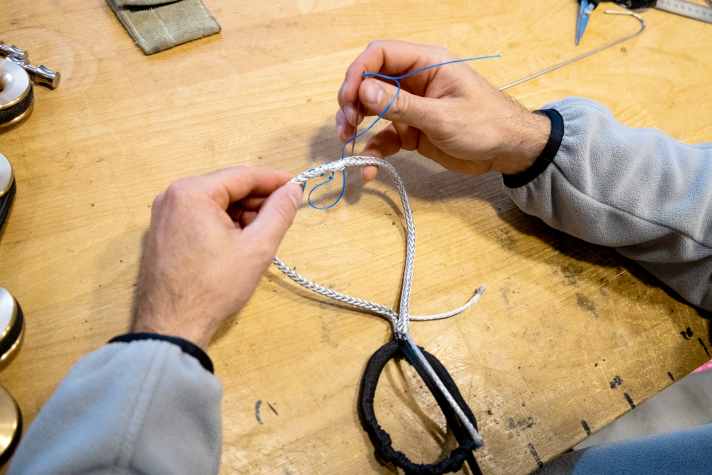

9. thread into the core

Thread the splicing needle into a strand of the core and let it emerge at the mark. It should run at least 20 centimetres through the strand.

10. second loop

Thread on the end of the second strand and pull it into the core with the splicing needle until the markings on the core touch each other.

11. create a closed ring

Repeat steps 9 and 10 on the second strand to join the core into a closed ring. Milk the splice smooth from the centre.

12. sewing

The splice is sewn so that it cannot come loose in the next steps. It is sufficient to secure the connection with a few stitches.

13. milking and marking

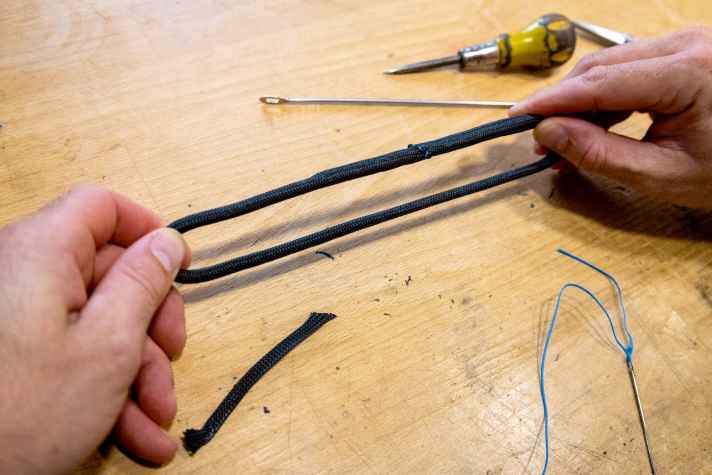

Milk the splice smooth again from the centre and mark how much material is left on the loose end pieces with the marker.

14. cutting to length

Pull the ends slightly out of the core and cut directly at the mark. If you don't have Dyneema scissors, use a new cutter knife.

15. rejuvenate

The core ends are tapered so that the splice has the optimum breaking load. To do this, pull four carding elements out of the braid at half the length ...

16. cut-off

... and cut off. Then pull out another four cardoons in the last quarter and cut off. Repeat the process on the other side.

17. ends into the core

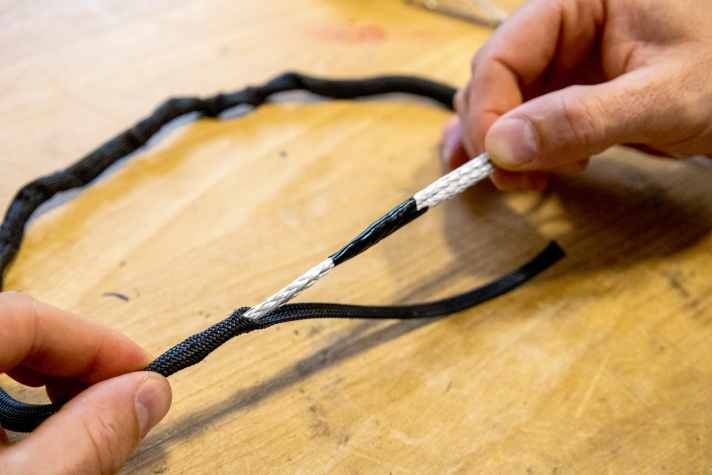

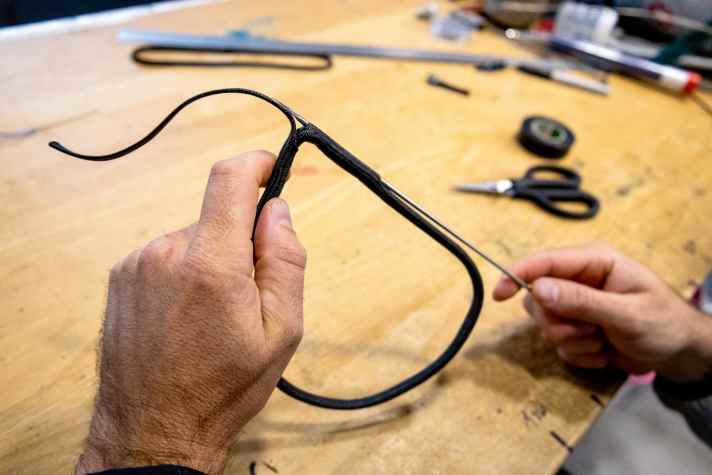

Milk the splice until the ends have disappeared into the core. Pull the loop back on. The splice should then be opposite the opening in the sheath.

18. fix transition

Tape the end of the casing tightly to the core strands. Only use a small amount of adhesive tape so that the area does not become too thick.

19. smoothing the sheath braid

Slide the braid over the glued area and milk the loop until the braid is evenly distributed all round and fits tightly.

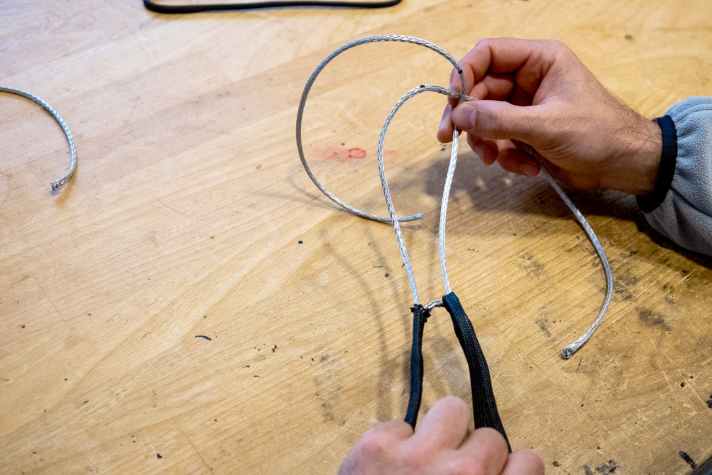

20. last splice

Insert the splicing needle into the sheath about ten centimetres before the overlap and allow it to exit where the sheath disappears into the other end.

21. pull loose end into the loop

Make sure that the splicing needle has not caught any of the core strands. Then thread on the loose end of the sheath and pull it into the loop.

22. couple with seam

At the connection point, the two sheath braids are coupled with a circumferential seam. Caution: Do not sew through the core!

23. follow-up work

When everything is sewn, pull the loose coat remnant out of the loop a little and cut it off diagonally. The loop is then milked until ...

24. result

... the end of the sheath has disappeared. The thickening does not matter - as the sheath can move on the core, it is hardly stressed.