Baltic Sea storm surge: On board - Experiences during the night of terror

YACHT-Redaktion

· 24.10.2023

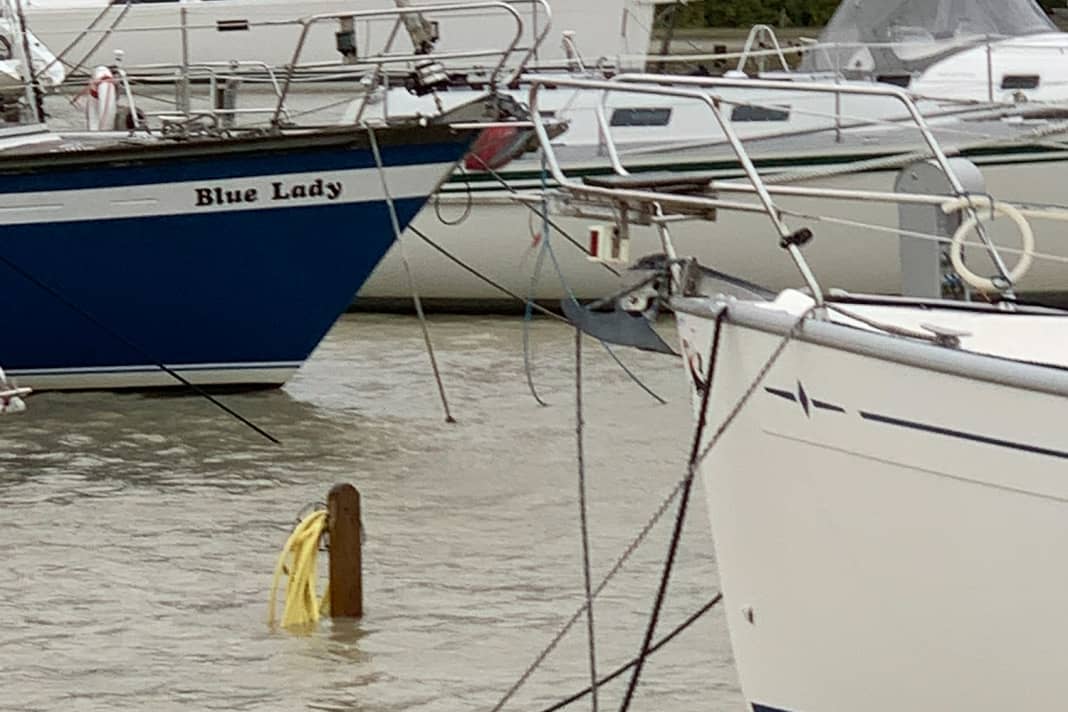

Trave: jetty gone, stairs as dinghy dock

When I arrive back at the Schwartau Sailing Club on Friday, the water is already up to the first step of the clubhouse and knee-deep over the jetties. Waders are in high demand and the local fishing shop is already sold out. But even if you can get to the front of the boat with dry feet, the pulpit is almost at head height at this water level. To get on board, a ladder is needed in addition to the fishing trousers. It's easier to use the dinghy and the bathing ladder on deck. I brought mine from home.

Since the devastating floods of 1989, the headlands on piles have been covered with slides. This means they have well over a metre of clearance. So everything still fits here. However, it has been clear since the morning that the piles at the stern will disappear into the water to an alarming extent, jeopardising the hold of the stern lines. Especially as the draft angle becomes steeper and steeper as the water level rises.

For this reason, a group of owners had already secured the stern lines in the morning, where they had not already been done, by placing them under the metal bar that is normally intended to prevent them from slipping downwards. The boats also had to be moved from the only floating dock. Here the piles proved to be too short. So it was now also our task to secure the floating jetties with mooring lines. On the one hand, they should not drift away, but also not sit on their own piles when the water level drops later.

Afterwards, regular control laps are made with the trainer boat. In the evening, the sliders at the jetty also reach their upper limit. In the meantime, the water level has exceeded the 1.70 mark. That was the predicted maximum level for Lübeck. A team in waders checks the lines at the front, I'm in the coach boat, something has to be adjusted, we climb onto the yachts from the stern and tie the fore lines and check the fit of the aft lines.

In the meantime, photos and videos from Damp are already doing the rounds"

The breakers hit the harbour basin there, and even before the peak of the Baltic Sea storm surge, boats were already going down. Fortunately, we are far removed from this on the Trave, nine nautical miles inland. The wind is not quite as stormy and we are well protected from swell. Nevertheless, it would be disastrous if boats were to break away. With the wind direction, everything depends on the stern line to starboard. If the stern line slips, it can set off a chain reaction.

This is exactly what happens to the largest boat in the harbour. Fortunately, we notice it during an inspection trip and are able to secure it again. Due to its length, it protruded out of the box at the stern and was still held sideways by the dolphins. At the front, however, it was already lying on the jetty.

In between, there are always owners, the landing - By now, the fourth step is already in the water - in front of the clubhouse it becomes a dinghy dock. The mood is a mixture of concern for the boats and jetty, but also relief that we are not so badly affected by the Baltic storm surge in our sheltered location. Helping each other in such a difficult situation creates a sense of community, of us against the storm surge, so that the mood sometimes seems almost exuberant instead of one of constant worry.

The maximum level is reached at 1.85 above normal zero. The water level drops again at around 10 pm. This is clearly visible on the railing of the jetty, which is rising again, albeit slowly. One last round, just to be on the safe side. All the boats and the floating dock are moored. Around midnight, everyone makes their way on board. Waders or dinghies are used to get into the bunk, exhausted. Fortunately, the storm surge has a happy ending for us. It's not until 12 noon the next day that we can set foot on the jetty again without getting wet.

Michael Rinck

Sønderborg: Passenger only

Friday evening, nothing helps now. The wind is roaring, but the bigger problem is the confused waves in Sønderborg harbour, which have been building up for days now as the water from the east has buried the piers. The boat dances, bucks and jumps, the mooring lines jolt into the cleats. The easterly wind hits the boat from the starboard side, the waves more from aft. The harbour lights are switched off and it is raining cats and dogs. Occasional torch lights dance around on the few other inhabited boats. Now everyone is on their own, you can't help anyone else, and you won't be helped yourself either.

What remains is the good feeling of having tried everything. The waterproof bin contains my wallet, car keys, a multitool (what for?), distress flares, a handheld radio, a torch is tied to the lid and I've been wearing my oilskin and lifejacket since this morning.

While it was still light, a friend had visited me in the dinghy and brought over some tonic, but the drink didn't really agree with me. So I made some coffee and took further measures. The slipping stern lines were reattached with tensioning straps and lashings. The whole thing with long arms under water out of the bucking dinghy. A second stern spring was deployed to a third pole to windward. We paddled ashore with our friend to drop him off and returned to the boat in the dinghy. We shimmy from boat to boat over the jetty to the dinghy car park. I let myself drift back and have to keep an eye on my boat, as behind it, after a neighbouring berth, there is only the pier, which is covered by fire. It works.

In the last light, I can see a motorboat of about 60 feet as it bumps along the pier and drifts out of the harbour. Then night falls.

I'm just a passenger. Once the emergency kit is packed, all that remains is to run through the possible scenarios. An evacuation would be more dangerous than staying on board in the event of an accident.

Worst case: The lines break and we shoot the motorboat downwind"

It's only hanging on to one stern line and two forward, drifting in a packet towards the next piles, which are already far under water. Then came the pier in question, where we would wear ourselves out until we sank.

After a bang on the bow, I discover a one-and-a-half metre long piece of plank with one of the fore lines still hanging limply from it, a little way from the jetty. After a few hours, the two stern lines, secured several times, slip off the windward pole. Only the three springs and the remaining fore lines are still holding. They have to, otherwise that's it.

But everything can be improved. At the jetty to windward, a motorboat breaks free, drifts across the jetty, knocks over a power column, drifts on and points towards us. As far as we can make out in the light of the handheld spotlight, it is only hanging on to a stern line. If it doesn't hold, we will be shot down. So we lower the transom and lash the dinghy to the stern as a last line of defence. And watch. There's enough to do in the meantime. From the shore, balewood, large branches and other rubbish drift towards us.

The mental exhaustion adds to the physical exhaustion. As a precaution, I set myself an alarm clock for every half hour and lie down in the saloon under the midship cleat, on which the springs regularly make an audible noise. When the noise stops, the unimaginable is close at hand.

And then it actually happens: the wind drops, of course not without occasionally picking up again as if in protest. And the unyielding woman gives in: the level curve actually drops again 30 centimetres above the forecast peak. Done.

Fridtjof Gunkel

Strande: Abandoning ship

It's not quite midday on Friday when the fan heater below deck stops supporting my adventure. The harbour masters have started to prepare the entire area professionally for the coming weather. This includes switching off the electricity. I light the stove. If the gusts of wind weren't working the furling headsail so hard that it causes the entire rig to vibrate, it would be so cosy here below deck.

Through the drops on the windows, I can see that the only people on the promenade, which is now almost reached by the waves in the harbour basin, are people who have a job to do or are watching their ships from a safe distance.

Nobody voluntarily strays onto the dancing floating dock anymore"

At the back of the harbour, volunteers are catching a yacht that has broken loose; the yacht club has provided the rib. At some point, the helpers moor it and go ashore, although there is still enough to do, but a decision has apparently been made in favour of personal protection. From now on, the DGzRS takes over.

I become thoughtful and put on my oilskin jacket to take another look at what is happening behind the windows. The stark contrast between the sides of my windows surprises me, to say the least. On deck, I have to hold on tightly because of the wind pressure and the boat's movements. From ashore, a policeman gives me hand signals, which I interpret as meaning that I'd better go back below deck.

There I prepare to move out. On deck, I've done everything I can to secure my ship. Seven mooring lines, five of them to windward at different points on land and on the ship, a stern line is tied deep to the stern post and secured against sliding up. If a neighbouring ship were to break free, it would be life-threatening to try to shore it up or even moor it again on your own. Being on board would be too dangerous for me in such a situation. Getting ashore is also becoming increasingly difficult as the water continues to rise and it will be dark in a few hours. Shortly afterwards, the stove is switched off. I stand ashore with my bag.

The gusts of wind start to subside before midnight. That's around two hours earlier than expected. During the hourly check-up, I was standing in the water on the promenade last, now it's gradually starting to sink. At some point during the night, the spook is over. Switched off like the electricity.

Breathing a sigh of relief doesn't work"

However, we cannot breathe a sigh of relief. There were no personal injuries here in Strande. No boats sunk either. Nevertheless, the extent of the devastation is enough to dampen the joy over the undamaged ship.

At the edge of the harbour basin, four stranded boats lie high and dry, having broken free during the night. The entire harbour area is covered in mountains of seaweed. The shipyard of the Kiel Yacht Club is working with all available resources to salvage the boats and yachts, some of which are still afloat.

Thoughtfully, I dismantle the many mooring lines again. My ship has been lucky once again.

Lasse Johannsen

Marina Minde: Back to the boat

Like my colleagues, I had already spent the two nights on board before the peak of the storm and high tide to check my lines at regular intervals. I had tied tightening loop knots to the wooden dolphins on my stern lines in the hope that they would hold even under water. By 8 o'clock on Friday morning, the water was already rubber boot high on large parts of the Marina Minde site in the Danish part of the Flensburg Fjord. The harbour master's building resembled an island in the constantly rising water.

I was out and about all day documenting the approaching storm surge. I witnessed many terrifying scenes on the German Baltic coast: a houseboat torn loose, for example, drifting maraudingly through the Wiking marina in Schleswig, past yachts that had already sunk and ships with wildly flapping foresails hanging in tatters. A red steel yacht had also broken free and drifted into the opposite embankment, while a sailing cutter was drifting west of the striking Viking tower together with a piece of jetty that had been torn loose and was still attached to a mooring line. The situation was similarly dramatic in Damp, where individual owners were still desperately fighting to save their boats. But here too, three yachts had already run aground and an end to the storm was nowhere in sight. The THW and fire brigade had already taken up position and fluttering tape was used to keep onlookers away from the boiling cauldron.

I returned to the Flensburg Fjord in the evening with a more than queasy feeling to finally check on my own boat again. I aborted my first attempt to get to the jetty, the water seemed too deep - I hadn't bothered with a pair of waders in time. The harbour master Claus, who was returning from his patrol, was able to calm me down briefly and reassure me that all the boats were safe at the moment. As I said, for the time being. But what if a line is pushed over the pile or another boat breaks free and triggers a chain reaction?

So I pull myself together and strip down to my pants and oilskin jacket and slowly work my way to my floating dock in the dark"

An unreal and eerie atmosphere. Sometimes the cold water sloshes up to my belly button, flotsam such as plastic rubbish or bushes float past me. When I finally reach the boat, I realise that all the lines are still in place, including the stern lines, whose mooring poles are a good way under water.

To warm up, I crawl into my thick down sleeping bag and try to get some sleep. Hopelessly. The background noise is just too loud, although fortunately the marina is reasonably well covered by land. But according to the forecasts, the storm should subside sometime around midnight and the water level should drop again quickly. I was all the more surprised when the boat suddenly started bucking wildly at 1 a.m. and the incoming gusts became all the louder and more threatening. The wind must have shifted from north-east to south-east. So I went out on deck and checked everything again.

In the light of the torch, I notice that the windward lead line is beginning to fray on the jetty cleat. A second line is quickly put in place, but refloating turns out to be a challenge, as the floating jetty and bow alternately shoot upwards and the distance is correspondingly greater due to the longer leading lines. If I were to injure myself now, I would be on my own. But after a while I find the right timing and manage to get across safely. An hour and a half later, the spook is over and I fall asleep exhausted in full gear. The alarm goes off at 5 a.m. and, to my delight, the dolphins are already peeking out of the water again. That's it!

I bring the boat closer to the jetty again and jump off the boat. I almost slip into the water, because the floating dock has tilted on the guide dolphins during the short intermezzo during the night and is therefore falling ever more steeply as the water drains away. Could the jetty crash onto the boats in the worst-case scenario? Even though everything is actually over? I write a message to the harbour master, and less than 15 minutes later he arrives. However, as the weight of the jetty is enormous, he can't do anything either. But he reassures me once again and explains that, in his opinion, only parts of the jetty could break off, but that nothing will happen to the boats.

My boat and the whole of Marina Minde were very lucky, but my modest efforts and those of the harbour master's team also paid off. Two hours later in Schilksee, I realised just how close luck and misfortune are.

Morten Strauch