Swede 41 "Sleipnir": Archipelago cruiser and Swedish king

Lemkenhafen is a tranquil little village on Fehmarn, once a lonely fishing village in the west wind, now a holiday idyll that has spruced itself up in recent years. Cyclists stop off at the "Samoa" restaurant, tourists queue up in front of the "Aalkate", the holiday flats and car parks look brand new, and visitors sort their equipment in front of the surf shops or sit in the sun with a cappuccino. And as soon as the wind blows more than force three up here, the bay mutates into a race track: The kitesurfers zoom across the shallow Baltic Sea like colourful squadrons.

The tiny Lemkenhafen harbour still has one attraction to offer, but it is not signposted anywhere. The locals could easily put up a large sign above the entrance to the marina and write "Museum for floating Swedish cultural artefacts" in bold letters. Admission would even be free and the artefacts on display could be admired in rows. Lemkenhafen is also a collection point for archipelago cruisers: for those famous sea eagles from Sweden that are among the most elegant, slimmest, sharpest, sportiest and fastest yachts of all. And this has been the case for well over a hundred years, since the development of these lanky speedsters began in August 1896.

Other interesting archipelago cruisers:

In the marina, the rare feasts for the eyes lie in their boxes, lined up like pieces of jewellery on the dolphin chain. There are at least ten of them. Several 15-berth warping cruisers adorn the picture, many of them built in the heyday of the class between 1933 and 1941: the "Oj Oj", the "Reed Wing", the "Romance II". Next door, 22 and 30-metre archipelago cruisers, also of the best vintages, bob around, as well as several later "Swedes", the type of boat developed by Knud Reimers in 1975 as the bigger sister of the popular S30. Lemkenhafen is a small Mecca for the speedsters from the archipelago; it is not for nothing that a meeting is held here regularly under the heading "Slim and lean". And you would probably have to look a long time, even in Sweden, to find such a collection of typical Scandinavian boats.

Toughened combination of old and new

And then there is another ship that is characterised by its racy lines. But what is it? What is it that floats like an arrow in the harbour? The yacht looks old if you look at the lines, the hull, the eternally long overhangs and the flat superstructure. On the other hand, this vessel looks almost ultra-modern if you look at some of the details: new rigging, white mast, white boom. The fittings gleam in the sun, the self-tailing winches are the latest generation.

Standing and moving goods are also all the rage. What then, the viewer involuntarily asks. Old? New? Perhaps a heightened combination of both - from the best results that have emerged from the epochs of sailing? This morning, Richard Natmeßnig, 50 years old, psychotherapist and keen sailor, who realised a dream three years ago that goes beyond any therapy, is prancing across the brand new teak deck. The retro classic in question, floating there in the green water, is a special piece among Lemkenhafen's sleek beauties.

Natmeßnig, born in Austria, sailed on Lake Wörthersee as a teenager and his father regularly took him on trips to the Adriatic, where they cruised between Dubrovnik and the Kornati islands. It was nice and warm down there, but Natmeßnig later moved to the north of Germany for work and family reasons. His wife's uncle owned a yacht on which he sailed from then on, then came his three children, his career as a therapist, followed by repeated sailing summers on the Baltic Sea; trips along the German coasts, to the Danish South Sea. Natmeßnig loved the charm of the north, the small harbours, the rattling of the halyards in a strong westerly wind. But he had never owned a boat before.

Classic lines with state-of-the-art equipment

That was about to change, in 2016 to be precise. Natmeßnig was looking for a ship. One that was somehow old, but also new. It had to be fast, safe, comfortable, elegant and, above all, beautiful. One day he came across an advert, read the name of a Swedish idea, googled it and came across the Classic Swedish Yachts website. Underneath was the motto: "A classic - reborn modern."

Natmeßnig could hardly believe what he saw: a yacht whose classic lines enchanted him straight away; a yacht concept that at the same time impressed with its state-of-the-art equipment. This was a combination of tradition, history, performance, technology and elegance - all added up to sheer sailing pleasure. In short: Natmeßnig was staring at a boat that would probably make any sailor take tranquillisers - especially at the thought of personally ordering such a vessel. An initial email followed. A first conversation. A first exchange with those gentlemen who had hatched something extraordinary up there in Sweden.

Natmeßnig got to know Olof Hildebrand, the founder of Classic Swedish Yachts. He had joined forces with others to bring the cultural heritage of archipelago cruisers into the modern age. Sven-Olof Ridder, a designer and hydrodynamics expert who had already developed ships with Knud Reimers, also contributed to this. Back in the 1970s, the famous Scandinavian yacht designer had already given the classic long-keel boats a split lateral plan, made the hulls wider and more voluminous and enlarged the cabin in order to meet the increasing demands of touring sailors. The skerry cruiser was given its first lift and from then on was built in GRP.

The third resurrection of the archipelago cruisers

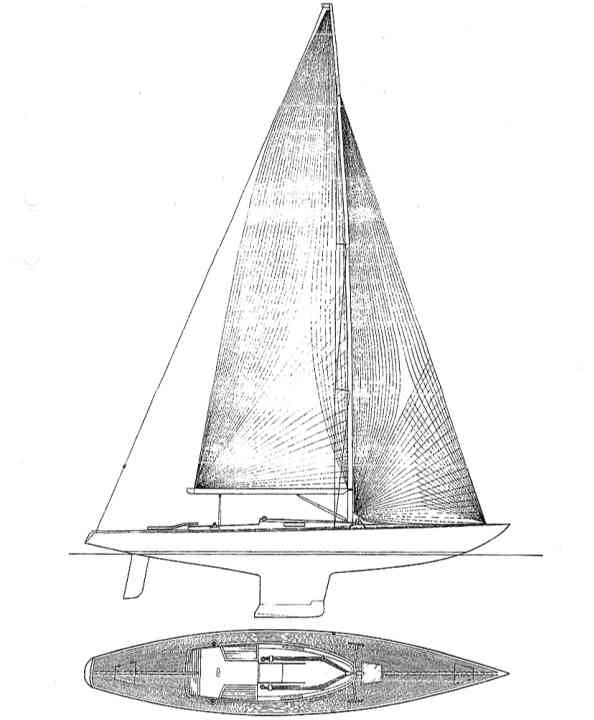

The idea today, in the third millennium: the good old skerry cruiser was to be resurrected after its first modernisation - with all the bells and whistles that the sailing world has to offer today. Natmeßnig actually went for it, he couldn't help himself. He ordered his brand new Swedish racing skerry in 2016 and took delivery of the Swede 41 yacht in 2018. "The lateral plan is still split," he explains, sitting in his cockpit, which is lined all around with light grey upholstery. "Today, the ship has a keel fin with a kind of small bomb underneath."

The yacht weighs just under four tonnes, 1900 kilograms of ballast, which also houses the 130-litre water tank in a stainless steel cassette. The smart solution already gives an idea of what the designers are aiming for today: to utilise every last bit of performance - without compromising on operation and comfort. And this is what it looks like in detail. Especially when Natmeßnig lets his eyes wander over the ship and explains what else has been added in the choice of equipment. "The 'Sleipnir' is my lifelong dream," he says. "If it's possible, then it's possible."

Carbon, wood, GRP- This warping cruiser combines all materials

The rig is made entirely of carbon, the boom, the 16 metre high mast. The shrouds are rod rigging, solid solid steel, thin, hardly any stretch. The sails from North Sails are 3Di membranes, laminated and tempered, with an attractive, light-coloured coating. With the Code Zero, the yacht brings 87 square metres to the wind - enough for the modern skerry to easily sail at eight knots. With the jib trimmed flat as a board, it is 66 square metres, more than twice as much surface area as the old S30 models once had.

Rosättra Båtvarv, where this Swede 41 was built as one of only three examples to date, also realised a few other delicacies that Natmeßnig attached great importance to. Teak deck. Mahogany superstructure, including 25 coats of varnish. Saloon: mahogany, oak. The blocks are all made of gleaming stainless steel, as are the powerful winches. The cleats can be lowered into the teak deck and, like the deck hatches, are also made of stainless steel. Trim lines, sheets, halyards: Almost everything here is made of Dyneema, partly covered for protection. The hull, on the other hand, is constructed from GRP, sandwich-laminated on both sides onto a 25-millimetre foam core. This also makes the boat light, strong and fast. For a skerry cruiser that nevertheless has such a classic appearance, this is an invisible but ground-breaking feature. It is comparable to an old sports car that is now built entirely from carbon fibre-reinforced plastics. To put it graphically: a wolf in modern sheep's clothing that would have made the boat builders of yesteryear drop their calf irons in amazement.

The skerry cruiser gives other sailors pause

Natmeßnig gets into his sea boots and adjusts his cap. He wants to sail. The conditions off Fehmarn are good, 5 Beaufort from the east, enough to get the Swede 41 going at full speed with the first and later the second reef. The sails are quickly set in the bay and we are already upwind. The "Sleipnir" lies on its side, the water gushing over the coaming. The log shows over seven knots in no time. Other sailors look over as we pass. Puzzled. Questioning. The old new Swede pulls so high upwind through the waves that you think the yacht is actually sailing head-on. And almost effortlessly.

At the tiller: hardly any pressure. The sails: as tight as aluminium walls. Sailing: pure joy, close to the water, close to the wind - close to the feeling it's all about. Feeling the boat right down to your fingertips, the wind, the feather-light power of propulsion. And yet you can still enjoy the feeling of travelling in a very traditional way and not sitting on a highly tuned high-tech rocket of the latest design.

"The Swedes around Olof Hildebrand had a good idea," Natmeßnig shouts into the wind. "They simply cut off the superstructures of the new Swedes!" In other words, they trimmed the last successors to the old archipelago cruisers back to their classic appearance by flattening and tapering the more powerful cabin superstructures of the 1970s models. This looks beautifully elegant again today, but may also sound like a reduction in comfort. However, this is not really the case when you go inside the yacht. Despite the small, flat space, modernity has also led to detailed solutions that make travelling on board extremely comfortable.

Optimum utilisation of space below deck

After four hours of cruising, after courses in all directions and a detour under the Fehmarnsund Bridge, the "Sleipnir" lies quietly back in the harbour. Natmeßnig enters the brightly lit saloon and explains a few details that are not immediately obvious. There's the panel for the electrics, neatly concealed behind a compartment door. There is the small chart table, under which - would you believe it - a marine toilet is hidden, which also works electrically. Two or three hand movements and you are sitting in a small separee; highly practical, highly efficient. And all this on a boat that is just 2.50 metres narrow.

Every centimetre of space is optimally used here. Even the small galley opposite, with storage compartments and sink. The passage to the foredeck opens up further cupboard space in fine wood. The true luxury, however, is only revealed to those who, after a soaking wet autumn day, drop into the double berth at the front. There, the tired sailor then rests on a pocket spring mattress, which can be preheated and ventilated using a small, almost silent fan. This ensures a cosy, warm night's sleep and zero humidity overnight. Air-conditioned rattling on the water - why not? It's part of the whole idea of bringing the classic archipelago cruiser into the modern age.

The best of the old and the best of the new

As you might have guessed, this also includes a modern electric motor. Natmeßnig sits in the cockpit again and lifts the floorboards. The black motor sits underneath - sleek and without any oil stains. Three batteries are housed in the right-hand locker, the fourth in the left-hand locker, right next to the refrigerator, which as a top loader is not even noticeable here, steals zero storage space inside and yet still offers enough space for plenty of manoeuvring. That's how it can work. A 120-year-old idea - raised to the standards of the third millennium.

Natmeßnig is visibly happy with his dream. "Everything is just right," he says. "I wouldn't know what to improve here." A perfect attitude to life under sail, which is due to a way of thinking that works not only in yacht building. In principle, the formula for success should have its charms: Take the best of the old and combine it with the best of the new. History and the present, fused into a sailing cream slice.

Richard Natmeßnig only went back to the annals for the name. The term "Sleipnir" comes from Norse mythology and in Icelandic prehistoric sagas stands for the eight-legged horse of the god Odin. The legendary mythical creature got its name because it literally "glided along" - on land, on water and in the air. The gliding Swede? The Austrians would say: right.

Technical data Swede 41 "Sleipnir"

- Design engineer:Ridder/Hildebrand

- Torso length: 12,45 m

- Waterline length: 9,70 m

- Width:2,50 m

- Depth: 1,78 m

- Weight: 3,8 t

- Ballast/proportion: 1,9 t/50 %

- Mainsail:38,0 m²

- Furling genoa (110 %):25,0 m²