"Wanderer III": A cruising yacht classic and the 96th degree of longitude

YACHT-Redaktion

· 02.09.2023

From Thies Matzen

Take: an old boat, a remote longitude in the Pacific, three couples. Add: a less connected and consumed world; letters and boats instead of bytes carrying messages around a more analogue world; plenty of salt. Set the temperature to an average of 25ºC; wait seventy years - and this story of "Wanderer III" at longitude 96ºW begins to reach deep back into a sailing era when readers still took time to read articles of the length of this one.

The boats, on the other hand, were rather short. By today's standards, it takes some imagination to picture the nine metres and twenty-seven of "Wanderer III" as a comfortable living space - but that's exactly what they have been to us for forty years. And nobody could have guessed in 1952, when she glided into her element at her launch in Burnham-on-Crouch, England, that she would one day be credited with an affinity for a Pacific longitude. And that seventy years later, in the midst of the great outdoors of the Falkland Islands, she would be waiting on a mooring specially laid for her and still be ready to sail to it again. Just like that - it would be the ninth time.

No other yacht has characterised the beginning of cruising sailing as much as this 30-foot wooden boat. Hardly any other yacht has travelled the world as far and wide as she has. She has been honoured twice with the prestigious Blue Water Medal, which has been awarded annually since 1922, for her voyages, which have shaped the sailing of an entire era. First in 1955 with the British sailing couple Eric and Susan Hiscock and then in 2011 with us.

"Wanderer III" has a way of persuading the owners to sail around the world

Yet "Wanderer III" is by no means the best, fastest, most comfortable or even that elusive ideal cruising yacht. But there is something about her that has kept her three blue-water owners - Eric and Susan Hiscock, Gisel Ahlers with partner Chantal Jourdan and my wife Kicki and me - sailing her around the world almost continuously for seventy years.

In 2006, shortly before Kicki and I once again set our course for the high southern latitudes - where we have mainly sailed ever since - we crossed an ocean with "Wanderer III" that she has sailed since 1953 as if it were the most common thing in the world: the Eastern Pacific. We were travelling in the westerly wind belt towards Chile, but the aft wind was hardly noticeable. Instead of reeling off light-footed, downwind miles as if in a frenzy, an alternation of lulls and fronts made for an uncomfortable stop-and-go.

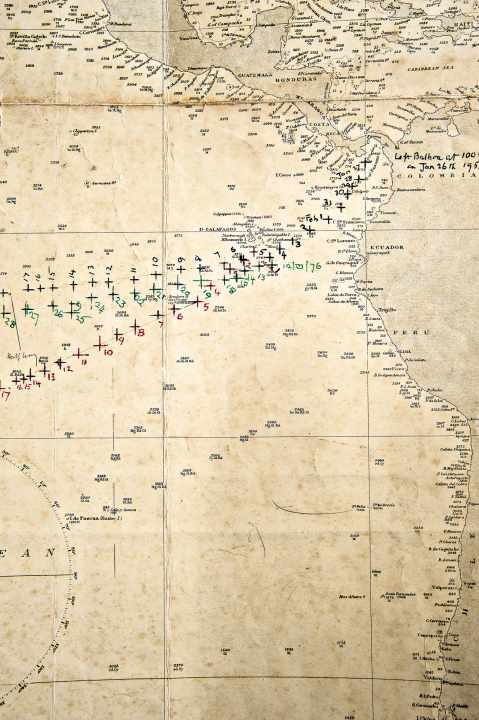

Below deck, I once again bent over the spread-out nautical chart from Gisel and Chantal's time. It had character; coffee stains created islands on it that were not islands. On an earlier voyage, I had added blank paper to enlarge the ocean that the map represented. A sextant elevation placed us in the shape of a small cross at 39º 24'S/95º 58'W; that was us, "Wanderer III" was right there.

At some point, I became aware of the many other noon altitude crosses scattered across the paper surface. My eyes travelled south and north along our longitude - we were only two minutes away from 96ºW. Its line stretched northwards towards Mexico, untouched by any landmass, where it was lost in continental inconspicuousness. Southwards, it ran unhindered through the centre of the Pacific, directly into one of the world's loneliest ocean areas as far as Antarctica. It was a landless loner. No question: anyone who crossed it was definitely on a long journey.

Blind date in the Pacific nowhere

I had just marked a sixth cross on it in pencil - next to one of Gisel's, five of ours - when I realised that two more would have to be added, namely those of Eric and Susan's two circumnavigations on "Wanderer III" in the fifties and sixties. It was at that precise moment that it really sank in: the eighth meeting of "Wanderer III" with this remote longitude in the Pacific nowhere had just taken place.

The pencil crosses represented nothing less than eight unique sea moments on it, spanning over half a century. What exactly had allowed "Wanderer III" to create them again and again? What exactly had enabled her to survive two reef strandings, a capsize, several knock-downs and countless storms over more than 300,000 nautical miles sailed?

On the 14th day of their first passage in the Pacific in 1953 - from Panama to the Marquesas on the trade wind route around the world - the perennial bananas in the forepeak were overripe. "Falling like leaves in autumn," Eric wrote almost poetically in the logbook on 8 February 1953. His notes are astonishingly informal, less formal, they do without many technical lists of quantifiable values on air pressure, wind and weather, but are narrative; in words instead of numbers, with a note of the daily midday position.

First Pacific passage for "Wanderer III" is a tough one

But at 4º 41'S/96º 08'W the poetry was over: "The movement is terrible. For breakfast, the cooker, complete with kettle and pot of boiling water, ripped itself off its gimbal. Threw away the last bananas." And shortly afterwards: "The movement is just too much."

After 1,482 of the 4,000 nautical mile passage, they had long passed the Galapagos Islands. The wind had increased steadily throughout the night and they were pushing westwards at six knots.

"I tried to make her self-steering with the main furled and the jib held back ... but she turns out not to be well-balanced and only holds her course for a few seconds in a beam reach. Giles should study the 'metacentric shelf'."

"Back to the drawing board, Giles," Eric seems to suggest to the boat designer of the "Wanderer III", Laurent Giles, about a year after her launch. This is almost heresy and not typical of Eric. But at this moment in the logbook entry, he doesn't seem to have been very cheerful.

"The sky is mostly overcast. This is not what I imagined the south-east trade wind to be like. A gloomy day. Before dinner we reef down to the second reef. Susan is very tired, and she had the first night watch but couldn't sleep, while I could barely stay awake on deck."

"Wanderer's" fast, jerky movements and the strain of constant hand steering with the resulting lack of sleep dominate the entries in the logbook. Wind steering systems did not yet exist. Sleep was rare in the under-manned blue water sailing of the fifties.

"Wanderer III" hardly seems suitable for the high latitudes for the Hiscocks

Downwind, her long keel and large lateral plan "Wanderer III" hold her course well, and two identical headsails, one on port and one on starboard, effortlessly stabilise the course downwind. However, I have never had to steer by hand for any length of time on long passages, as I still have the services of her first windvane to fall back on. It is one of the two prototypes that its inventor Blondie Hasler installed simultaneously on his famous folk boat "Jester" and on "Wanderer III" in the mid-sixties. It has logged more than 230,000 nautical miles to date, still with original parts. It is simple, has never caused any problems and still makes me believe that "Wanderer" is perfectly balanced.

At their first meeting with longitude 96º W, however, Eric and Susan clearly disagreed. It wasn't until well after halfway to Nuku Hiva that they were finally able to celebrate a perfect sailing day - on a Friday the 13th - on the forecastle with rum punch and tinned salted peanuts.

After her first circumnavigation, her owner Eric Hiscock mused: "'Wanderer III' is surely the smallest boat in which a level-headed person with genuine respect for the sea would want to cruise an ocean."

"Wanderer III" is a mirror of the times

The knowledge and mindset of the fifties characterised their design. Nobody knew exactly how small a boat could be to get it safely around the world; and how strong it had to be built. This was countered with larger dimensions in critical areas - in the bilge, the mast area - and with a myriad of stiffening bulkheads integrated with fore-and-aft guides. The British liked their yachts compartmentalised and not open.

The 9.27 metre long "Wanderer III" is only 2.56 metres wide - for the simple, almost ridiculous reason that the construction price of a yacht in 1952 was based on the Thames Tonnage used at the time; and this in turn weighted the width excessively, so narrow was synonymous with cheaper. Moreover, nobody questioned why a nine-tonne yacht should have to carry around three tonnes of lead for its entire life. But after "Wanderer's" first circumnavigation, Eric did just that. Under the impression of her sleep-killing lurching and rolling and the encounters with wider American yachts with a shallower draught, his preferences changed.

His "ideal yacht", he wrote in 1957, was on the one hand "the largest one could afford, but with a limit of 15 tonnes displacement". In other words, about 40 feet long, eleven feet wide, with a draught of slightly less than 1.80 metres. Aft with a short, overhanging transom for more buoyancy as a direct response to the wet cockpit of his third "Wanderer". With space on deck where you can sleep outside in the tropics - much missed on the "Drei"; a cutter rig with a short bowsprit - for plenty of sailing power; and with plenty of engine power - anything bigger than the 4 hp Stuart-Turner of the "Drei". In short: a type of boat of which thousands were to be built in the seventies and eighties, although most of them were made of fibreglass.

For Eric, this was little more than a mental exercise at the time; he and Susan could not afford such a ship. And why should they? The "Three" had fully confirmed their trust and never let them down once.

Susan and Eric become repeat offenders

In 1959, they set off from England on their second circumnavigation, again along the classic circumnavigation route, soon christened the "Hiscock Highway". This time they set course for Mangareva in the East Pacific and crossed the 96th meridian a little further south than the first time. And again it gave them quite a hard time.

"At Susan's suggestion we turned in for six hours so we could both get some sleep. Took the jib down at 0600, unbelievable rolling at times, it even catapulted a saucer out of its holder. Everything is the wrong way round on this bow: galley to windward instead of leeward makes cooking extremely difficult, chart table to leeward sends blood to my head - and, as we both prefer to sleep on the right side of our bodies, our faces are pressed hard onto the mattress and our elbows, which were causing us problems before, are paralysed ... Susan's stomach is better, mine is still annoying."

This logbook entry from 6 March 1960 makes me wonder: How can it be that I hardly feel this rolling and lurching? Am I really so insensitive and insensitive to movement? Or have I - since I hardly ever had to steer by hand on long voyages, except in polar waters with drift ice - simply never experienced the same excessive and continuous exhaustion as she did?

Despite shortcomings, "Wanderer III" remains favourite yacht

Laurent Giles gave his own answer to the apparent shortcomings of the "Wanderer III" with the design of his 30-foot Wanderer class. It is slightly wider, with a higher freeboard, a continuous deckhouse instead of the stepped one, and therefore with a larger cabin. I have never sailed a Wanderer-class boat, but in purely aesthetic terms - for me - there is simply no comparison with the "Drei".

Eric's lamentations may ultimately have prevented the "Wanderer III" from becoming a popular design with a correspondingly large number of replicas - which would have been expected, given that her voyages inspired entire generations of sailors worldwide. And yet, after 110,000 nautical miles sailed together and despite all the misfortunes at 96º W, she remained Eric and Susan's declared favourite yacht for the rest of their lives.

Third circumnavigation with new owners

Between 1974 and 1979, Gisel and Chantal sailed "Wanderer III" around the world for a third time. Unlike Eric and now me, Gisel hardly ever wrote a word and took very few photographs. Nevertheless, of the three of us, he is the real storyteller. His powers of observation and ability to immerse himself in the smallest details and convey them across a table over hot tea and fresh brown bread are unrivalled. He tells wonderfully intricate stories that are a pleasure to listen to, but not to read. That's how I got to know him in Kiel in 1982: as a storyteller and - it felt like - the only German with an inordinate amount of time.

Not long before I met him for the first time, he had sailed "Wanderer III" single-handed through the Indian Ocean while his partner Chantal was ferrying another yacht - and tragically died in the process. After 15 years of long-distance sailing, most recently on "Wanderer III", Gisel said he would probably not be sailing for a while. I left him a phone number - he had dialled it later that year and said he wanted me to keep "Wanderer III" moving on the oceans. It determined the direction of my life.

Today, in his mid-seventies, he lives on Mallorca, where I last met him. Apart from the encounter in a crazy dream in which he made the astonishing remark: "Thies, I forgot to tell you that 'Wanderer' has a cellar", I hadn't seen him for a whole eight years.

Few footprints of Gisel and Chantal

That mysterious extra storage space had unfortunately remained as much in the dark as parts of his "Wanderer" story. I only had one tiny clue about Gisel and Chantal's rendezvous at 96º W: the sketch of a freighter near the equator on the chart of the Eastern Pacific that he had passed on to me.

There stood Gisel on Mallorca, tall and slim, a warm smile on his face, his upper body slightly bent forward as always; he carried this adaptation of "Wanderer's" small dimensions into his later life. Both Gisel and Chantal were too tall to fit into the Wanderer III, which was designed for the shorter Hiscocks. They could not stand upright in the cabin and could not stretch out fully in the bunks. Where our wood-burning stove stands today, right next to the mast, their feet dangled out of the bunks and hung in the air.

The fact that Gisel is not a man of extensive modernisation and repairs was "Wanderer's" - and our - good fortune. He preferred to devote himself to the details. He was able to fully immerse himself in carving small things such as the pockwood handles of our winch cranks or cleats; and Laurent Giles' logo was screwed to the bulwark with not seven, but 27 bronze screws. All these things are still with us; only his perfect paintwork has not remained.

Lost and living memories

Sitting with Gisel in his Mallorcan orange grove, it was now me, not him, who was interested in the details. Instead of German brown bread we had olives, instead of tea we had wine, while Kicki and I listened to his stories for days on end. In August 1975, for example, he replaced all the galvanised pontoons and the bow and stern pulpit with stainless steel ones at the renowned Goudy & Stevens boatyard in East Boothbay, Maine. And the stainless 1x19 forestay, whose skilful splicing I had admired for many years? He had it made simply because it was feasible. And what about that sketch of a freighter at 96º W on the chart? I don't know, he couldn't remember it. "But," he sank into thought, "the passage to the Marquesas was pure magic."

Just like for us.

Our first trip to the Pacific was the fourth for "Wanderer III"; and her third between the Galapagos Islands and the Marquesas. She steered herself, the sheets required almost no corrections - it was like a repeat of the Hiscocks' perfect sailing day on Friday the 13th in 1953.

On my map - Gisel's old one - two lines with very evenly spaced crosses ran parallel to the equator from the Galapagos Islands to the west. They marked Gisel's and Chantal's course and now ours. Each new cross drawn daily for our midday position stuck close to one of Gisel's and Chantal's; our westbound marks were almost the same.

Race on the nautical chart

On the spur of the moment, more out of curiosity, I plotted the daily positions of Eric and Susan's trips, and suddenly the journey became a race, sailed in the same boat but in different decades - by the Hiscocks in 1953, by Gisel and Chantal in 1976, and by us in 1991. Sometimes we were in the lead, sometimes one of them - until finally, 300 miles off Nuku Hiva, we were hopelessly stuck in a lull. Even when the wind returned, we were soon to fall further behind - due to a slowdown of a completely different kind.

Like hardly any other boat, "Wanderer III" has characterised the pattern of classic circumnavigations. You leave your home harbour, sail around the world in a rapid succession of passages along the trade wind route, touching one place on the way to the next and returning within a predetermined period of time. This is typically around three years. Both the Hiscocks and Gisel and Chantal followed this pattern. And, up to a point, so do we in the broadest sense.

The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway

My illness with hepatitis B then changed a lot of things. I fell ill on an uninhabited Tuamotu atoll called Motutunga. We were alone, with no means of communication, nobody knew where we were. Weakened by the hepatitis, it was impossible to leave the atoll. It was too beautiful for that. It held me physically, but also metaphysically captive - the tonal balance of the constant trade winds over my bunk was hallucinatory. Looking back at Motutunga, I realise that it is right here, in my tenth year on Wanderer, that we really merged into something completely separate; into her third story - the one with us and ours with her.

My hepatitis triggered something that made us break with the traditional Hiscock continuum - from Panama to New Zealand in one season. In the early 1990s, as a foreign yacht in French Polynesia, you needed a valid reason to be allowed to stay there during the cyclone season. When we arrived, still clearly weakened, I met the criteria. But six months non-stop in Tahiti or even on Moorea were not very appealing. As soon as I was halfway back in trim, we sailed northwards to the Kiribati Line archipelago on the equator during the cyclone season.

Once there, we stayed - and all plans fizzled out. The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway - the standard trade wind route around the world - and the remnants of a schedule-orientated impatience in me - they dissolved and disappeared. We had sailed into the slow-beating heart of the Pacific. Without my hepatitis, we would probably have continued the journey to my Samoan family and on to New Zealand. Instead, we were now fully absorbing the slowness of the Pacific and its inhabitants; we were in an ocean full of time. This experience set the standard for all our subsequent voyages in the Pacific, the Indian Ocean and later in the Southern Ocean.

From a yacht sailing around the world, it became a platform for being in this world

It also had a significant impact on my perception of "Wanderer" itself and the meaning it had for me. All yachting narcissism was overcome because of its insignificance. From a yacht travelling around the world, she became a fantastic platform to be in this world.

Before I left Europe on "Wanderer III" in 1987, I was still harbouring the idea of building a larger wooden boat myself after my return, one in the style of Laurent Giles' "Dyarchy", traditionally planked. The idea was to sail it hard after completion, set course for Chile, caulk the hull again and then coat it with copper where copper should be cheap. The second part of my idea revealed glaring gaps in my understanding of macroeconomics.

In 2000 in Chile, nine years after the decelerating diversions to the Line Islands, we had long realised that the only copper-plated boat we would ever own would be "Wanderer III". Because of her character, her simplicity, her small size and aesthetics, because of what she allows us to do, and because of her nature to be perfect for all her imperfections. Grow - yes, but not in size. If you accept the challenge of being satisfied in the small and simple, then there is hardly a better boat.

A whole range of adjectives for 96º W

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, after two years in the Falklands and South Georgia, we had just painstakingly cruised northwards through Chile's Patagonian channels. Despite a few broken frames and colossal blows in the Southern Ocean, she had never leaked. We wanted to keep it that way and intended to carry out preventive repairs in New Zealand. With this in mind, we set sail from Puerto Montt, Chile, into the Pacific for our fifth encounter with 96º W.

The four previous meetings, all via Panama, had either been "magical" - Gisel's and ours - or "a bit too rough" - the Hiscocks'. This time, "Wanderer III" was turning on her own axis; we were drifting in the doldrums. Under a seemingly endless grey sky, a constant breeze had kept us going for several hundred miles west of Chile's coast on a north-westerly course to latitude 17º 30' south. But then, on the 22nd day at sea, we slid onto a magnet. At least that's what it felt like. Everything stopped suddenly, almost seamlessly: the wind, our movement, even the grey of the sky. It was as if we had sailed into the middle of a still, unchanging dreamscape.

"For the first time, overwhelming farsightedness, clearly contoured, with sharply drawn mountain ranges nothing more than unexplored cloudscapes, dream islands in the distance - reality and dream interpretation indistinguishable from nothing," I wrote in the logbook on 7 August 2000. All that remained for us was to drift powerlessly. If it was the 96º W's sole intention to invent days completely detached from human ambitions and to let us recognise them through "Wanderer", then it succeeded.

Course to New Zealand for restoration

The calm only lasted four days, but it gave barnacles a chance to take over the underwater hull. This in turn extended our passage to Penrhyn in the Cook Islands to 54 days. From there we sailed to New Zealand and put "Wanderer III" ashore for her half-century facelift. Quiet days were rare from then on. Every single day for well over a year was dedicated to her restoration.

It was here in New Zealand, after the Hiscocks had sold everything in England in 1974 and had become homeless sea nomads on their new steel ketch "Wanderer IV", that they received a letter from Bill Tilman. Tilman was another sailing icon of the time and had been the first to sail the high Arctic and Antarctic latitudes on various Bristol Pilot cutters - most famously his "Mischief". "I am not surprised," he writes to Eric and Susan, "that you are at a loss for new destinations for your next sailing voyages, as you have explored almost every corner of the globe. With the exception of where you are now, the only peaceful areas left are those that are still uninhabited by humans."

Declared goal: "Wanderer III" should not need a slipway for many years to come

If this was his sentiment almost half a century ago, how much more does it resonate in our reality today. Tilman's places of unpeopled nature have long attracted us. We intended to spend long periods in the Ultima Thules of our Earth, where repair is either difficult or non-existent. I wanted Wanderer III to require no structural intervention or even a slipway for many years. I was convinced that, although small and made of wood, she could survive in the rugged high latitudes into old age due to her original construction standard and the longevity built into her. Ultimately, these gifts also form the backbone of each of her eight 96º W crosses. They are the reason for her dry bilge.

Their longevity is based on a triptych of factors. First and foremost, the combination of owner, boat designer and boat builder. Eric Hiscock knew exactly what he wanted in 1952, Laurent Giles was an internationally renowned yacht designer, and William King's shipyard in Burnham-on-Crouch delivered the best quality in the country. The boat builders used carefully selected and dried wood, and the wood joints were perfect.

The second element of the triptych is the construction. The slender Karweel hull has very narrow Kalfat seams, an elm keel, elastic Sitka spruce fore-and-aft strakes, sterns, deadwood and deck beams made of grown oak - and not a drop of glue. The dimensions of all hull parts subject to particular loads, especially in the bilge, are oversized. The same applies to her hardwood panelling made of iroko. And then there are her metal connections; today they are almost exclusively made of copper. For a wooden boat, copper is almost like a source of eternal youth; all originally galvanised iron has been eliminated from the hull. And where copper is too soft to be used, as in the ballast keel bolts or metal floor cradles, aluminium-nickel-bronze is now used.

"Wanderer III" literally beckons to be groomed

But even this lifetime's advance of an exceptionally well thought-out design would not necessarily have been enough to allow her to sail more than 300,000 nautical miles in all the world's oceans without any problems if it were not for her three owners: Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and me. We filled her with voyages, we all lived on her, we admired her dearly - still do. It's not too big, on the contrary: it's small, pretty and harmonious. She literally beckons you to look after her. This is at least as important for its longevity as every structural detail. And, of course, like luck.

In 2003, on the very first voyage after the restoration of "Wanderer III" in New Zealand, we ended up on a reef in New Caledonia. Thanks to her new frames, her new copper plating, another repair and that all-important dose of luck, we were able to return to sailing. She survived a demanding test trip to Tasmania and on to New Zealand's sub-Antarctic islands without any leaks, giving us back the confidence we needed in her.

At the end of April 2005, at the beginning of the southern winter, we set off on a 71-day passage into the Southern Ocean from Dunedin, New Zealand, back to Chile. On the 59th day, we reached a position where God was playing chess with the surrounding highs and lows, but had obviously fallen asleep. Because without the slightest hint of change, it had been blowing at 9 to 10 Beaufort for days. We were lying at 39º S in a five-day storm. Five long days that we drifted back across longitude 96º W. Nevertheless, two characteristics of "Wanderers" that modern yachts no longer possess provided us with welcome comfort during these days: firstly, their ability to lie safely at anchor and secondly, the soothing muffling of the external howling in their cabin.

Double turning as relief valve

She turns unusually well, even under trysail alone. The ten-tonne weight of her hull in combination with her long lateral plan reduces her drift; above all, this makes it possible for her to sail upwind from a lee shore even at 40 knots under sail. This is an absolutely essential quality for a small, lightly motorised yacht like "Wanderer III", especially along the coasts in the high latitudes. It is the main reason why she can be sailed in these regions at all.

Once we had turned it round, it felt as if we had activated a relief valve, released the pressure and entered a state of alert slumber. When we closed the hatch and slipped down into the cabin, the over-excited howling outside lost its bite.

It is below deck, especially in storms, that the sound of a boat either encourages confidence or releases nerves. "Wanderer's" soothing sound kept all tension and irritability under control.

Sixth and seventh rendezvous

Something else, however, was worrying us. Our little Sony receiver had issued a rather absurd message: "Warning of falling spacecraft elements on 16 June 2005, between 0100 and 2300 UTC within the coordinates ..."

Exactly where we were. "What else are they going to throw at us?" shouted Kicki. But at some point, our chess-playing god made a move and allowed "Wanderer" to leave their lonely longitude behind for the sixth time.

The seventh rendezvous followed on New Year's Day 2006 at 25º 30' south - and was the diametric opposite of the sixth. Just as lengthy and awkward, only this time with absolutely no noise and zero wind - courtesy of the expanding Easter Island High. Compared to that five-day crossing, the two days we spent stuck on the line seemed like a hasty pit stop.

Turning point at 96º W

Whenever "Wanderer" encountered 96º W so far, she had left all signs of human activity behind her. That changed now. What I observed from the deck was more unsettling than any storm. I leaned my upper body over the railing and stared vertically into the sea to a point where the sun's rays converged concentrically in the deep blue. At some point, I focussed my gaze on tiny particles floating in the upper part of the sea column. Plankton. Or so it seemed.

I grabbed a bucket, dipped it in the sea and ... fished out fibres. What appeared to be plankton were actually plastic particles. The deep blue upper layer of the sea was strewn with a loosely woven carpet of the tiniest particles of our civilisation's rubbish. Everywhere I looked, I discovered plankton-like fluff and shreds, ejected by the achievements of a buzzing world somewhere else. This was not the densely populated North Pacific with its famous rubbish vortex, but a place far from human centres. This was where Thor Heyerdahl sailed through an almost untouched ocean with his "Kon-Tiki" in 1947. And where, a few years later, "Wanderer III" showed many of us our course for the first time.

At the beginning of the 1950s, the oceans were still unspoilt in their diversity of life. This is the time when "Wanderer's" story begins, around the same time as the ecologically precarious acceleration of consumer behaviour in our society. Since then, practically all our activities have flowed in one way or another into the sea that stores our excesses. Below deck, amidst its unchanged furnishings from another era, "Wanderer" may seem like a time machine. But on deck, surrounded by the sea, I think of her as a contemporary witness. Because she has witnessed the evolution of our current ecological dilemma from her well-travelled vantage point from the very beginning. For us, she is the ideal partner to peel back all these layers of the diversity of life - in beauty as well as in sorrow.

I realised that I could only see the carpet of plastic fluff when it was calm. As soon as it breaks up, it tears, escapes the eye and the sea surface shines and sparkles. Movement transcends so many things, including pollution.

Change and the future

I would certainly not have understood all this if we had hurried on this journey and not drifted windlessly. "Wanderer III" will never have a large engine, never carry much diesel. A large double berth is also out of the question. Like Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and I have learnt to live well with their spatial and temporal limitations. They suit us, we see them as an asset, we simply give them a lot of time and as a result we see other things and many things differently than if we did not.

Until recently, longitude 96º W was not so easy to reach from the Falkland Islands due to Covid, unless it was upwind around Cape Horn. This restriction also required time, patience, as perhaps the entire view of "Wanderer's" era required a moist eye that keeps up with the times. How much will have changed when she next finds herself with us at 96º W?

It will be wet, quiet, windless or stormy and - as always - no place to stay. But - I hope - its remoteness can still be felt, even in me.