Almost every lover of beautiful yachts knows that Henningsen & Steckmest in Kappeln-Grauhöft stands for perfect boatbuilding craftsmanship. There on the Schlei, the waterway in Germany with the highest density of companies in the water sports industry, they have been building yachts of the very highest quality since 1958. The range of Scalar types from 31 to 40 feet is well known. The latter was not built by Rolf Steckmest himself, but by Georg Nissen from Laboe.

However, in addition to the famous scalars, Henningsen & Steckmest also creates unique pieces such as the "Gaudeamus II". The boat with the construction number 145 was built by Henningsen & Steckmest in 2013 and featured in YACHT.

Why a 45-foot long keeler as a designated one-off construction? Hauke Steckmest, Rolf's son who joined the company along with his brother Malte, explained to YACHT at the time: "We can actually do much more in boatbuilding than is known, we no longer want to be restricted to scalars, but also want to produce special one-offs. So this order came at just the right time."

Seaworthy, solid, pleasing appearance- the specifications of Laurin's Koster boats

It also has a bizarre history. The owner from Hamburg, who does not wish to be named, had sailed a Laurin Koster for around 30 years, which had already been built by Henningsen & Steckmest in 1965. These are double-enders based on a design by Arvid Laurin (1901-1998). Born in Lysekil on the Swedish west coast, the mechanical engineer and naval aviator was also a silver medallist in the Star boat at the 1936 Olympic sailing competitions in Kiel. After his active racing days, Laurin began to think about ocean-going yachts and further developed the traditional Koster boats (named after the Koster Islands) that were widespread on the west coast.

Laurin once explained: "I wanted a boat that was seaworthy and solid, but didn't look like a cigar box at the same time." Several types were created, starting with the L 28, which was first built in wood and later in GRP. Wooden Kosters were built over 45 years, 95 can be found in the register of a kind of class association. Most of the boats were built in Sweden, but some were also built further afield, such as in the USA or Hong Kong, and one was built in Germany.

The owner had sold this boat, sailed a modern Danish design for around five years, had grown tired of it and wanted to buy his Laurin Koster back. The plan didn't work out and the man from Hamburg decided to rebuild the boat in the style of his old boat using modern technology.

This is where designer Georg Nissen came into play again, emphasising that he did not design the new boat, but merely modelled it on the Laurin Koster. He would not have been able to fall back on old plans.

Visually traditional, technically state-of-the-art

What Rolf Steckmest is pushing into the grey waters of the Schlei is a Laurin Koster in terms of its shape, long keel and pointed stern, but built in a more contemporary style and with modern equipment. Due to logistical considerations, the moulded mahogany hull was subcontracted to the Janssen & Renkhoff shipyard, a few shackle throws away from Henningsen & Steckmest. At the same time, Steckmest's men produced the bulkheads and parts of the interior. Visually still a Laurin Koster, "Gaudeamus II" (Latin for "Let us rejoice") offers hidden virtues from today's technology.

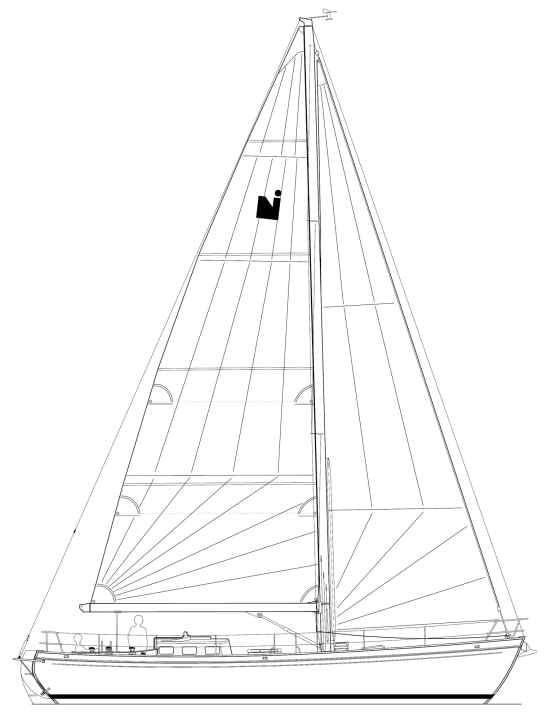

Designer Georg Nissen: "The new construction is around 600 kilograms lighter, the sail area is roughly the same, but the areas are distributed differently. Now the headsail hardly overlaps at all and is easier to handle thanks to the short sheet travel, just as it is done today." And: The rig is made of carbon fibre. The youngest Laurin Koster is therefore probably the only one to carry a rig from Southern Spars. It is also fitted with individually spliced Dyneema fabric. There is also an exhibition of Andersen winches. Six drums that work on one level and are also used for the lowered halyards. In combination with the sheer, minimalist teak deck, the effect is almost Wallyesque.

However, the owner and designer decided not to include a waldeck, the strongly rounded, usually white recess that leads into the side walls. However, the theme is visually picked up by the white-painted high bulwark.

Perfectly crafted boat building

The boat looks astonishing in many respects: it is perfectly crafted, has beautiful gleaming chrome fittings, stainless steel deck prisms, portholes and a deck skylight, reddish shimmering, perfectly painted freeboards and an equally beautiful superstructure - and could therefore pass for a gentleman's yacht. On the other hand, the shape, especially the stern, is reminiscent of a cutter. The boat also looks incredibly strong, solid and rigid - and on closer inspection or from certain perspectives, it is quite narrow. The mix of different maritime eras and scenes results in a very unique appearance.

The mix of different maritime eras and scenes results in a very unique appearance.

Parts of the construction are also almost hybrid. The hull shell consists of seven veneer strips glued diagonally to each other and is 32 millimetres thick in its entirety. With a final layer of veneer in the horizontal plane, the boat appears to be planked. The teak deck is glued under vacuum without screws, but there are still plugs.

The initial stability of the S-brace is also rather low compared to the basically gnarled look, but its shape ensures a soft entry into the wave and pleasant sea behaviour. You can also put it in positive terms: "Gaudeamus" is a combination of the best of not all, but many sailing worlds.

"Gaudeamus" sails faster than she looks

And she actually sails faster than she looks. With Schrick in the sheets, she overtakes a modern, sporty 42-foot yacht during the test drive. Even more impressive is the ease with which she can be steered and the straight-ahead behaviour typical of a long-keeler. The autopilot should have little work to do and consume little power. The steering commands are now transmitted from a Jefa system via a cardan shaft to the rudder at the pointed stern; on the old Laurin Koster, this was still done by cable pulls.

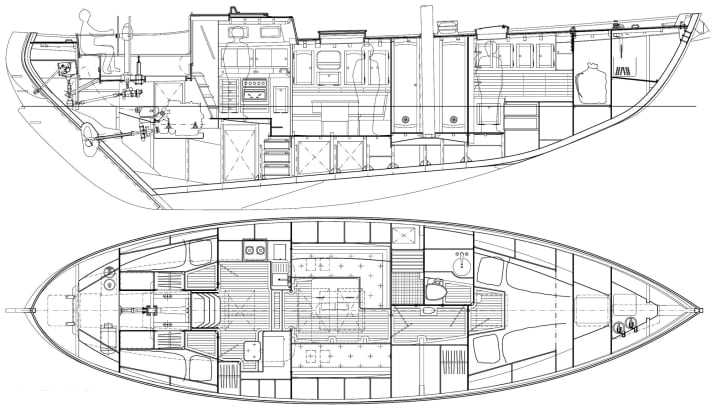

The crew doesn't have to work hard either. In addition to the generously dimensioned winches, a manual hydraulic system helps with sail handling; the backstay, mainsail foot and tube kicker as well as the genoa halyard are adjusted by pump stroke. The halyard tension is a particularly clever solution: the halyard only reaches as far as a cylinder mounted on the mast, which trims it. To retrieve and set the sail, the halyard loop is unhooked from the cylinder and operated with a winch using a deflected extension line; a neat solution that comes from the big boat scene.

Although the light wind allows the "Gaudeamus" to sail confidently, it also fails to demonstrate the actual strength of the S-shaped hull. There is no wave that would show the soft entry. "This comfy dip and the soft movements are typical of a hull with an S-frame. Also the lower initial stability. On the other hand, the capsize angle is enormous - 160 degrees with this boat! Modern boats only reach 120," reports designer Nissen.

In general, the boat radiates safety and seaworthiness. The deep cockpit also contributes to this. Or the portholes aft of the cabin superstructure, which not only provide light and air, but also allow communication from inside to outside during hacking without having to open the companionway. Or an engine that is easily accessible, even from above.

The interior is cosy and practical at the same time

The interior also appears to be primarily subordinated to the mantra of long sea journeys. It is cosy, comfortable and visually warm. Reddish wood in a perfect finish, people in the belly of the ship, in a sense of security. Cosy, dignified and elegant on the one hand, but also rustic, somehow gnarled and rustic on the other. There it is again, the dualism inherent in this ship. However, it is normal that the individual construction of an owner who can look back on many years of experience is very special. After all, the man has already travelled in Greenland, Spitsbergen and the Atlantic, which should leave its mark.

Various practical items can also be found below deck. A seawater pump, for example, which helps save drinking water for washing up and cooking. Then there is the deep bilge, which is more beautiful than many a boat from the outside. The deep wooden cavity is used to collect water, but is bone dry on the moulded ship. The tanks are also housed in the long keel, which is a full 2.05 metres deep. They are installed there out of the way and, from a sailing point of view, desirably far down, and the drinking water is stored cooler there than further up.

Flawless boat building in every detail

The aft section of the ship is slightly elevated. Two dog berths are accommodated in small cabins close to the navigation and companionway, where the on-call watch is located. Galley and navigation in front. One step lower is the central saloon under the mighty skylight, which is equipped with real sea berths. A huge cupboard is built into the passageway to the front, lit from the inside - no, this has never been seen on a Laurin Koster before. Opposite is a separate shower and toilet room. The owner's cabin with conventional berths and additional storage space is located in the foredeck. In front of this is a decent sailing load for everything that the small forecastle boxes cannot accommodate.

Even the laminated attachment of the bulkheads is so neatly executed that it did not have to be painted over.

The fittings are immaculate, the finish perfect, the joints, edges, mouldings, joints and connections precise, form-fitting, the floor does not creak. In addition, there are weir stanchions underneath and a white ceiling with clear varnished wooden deck beams, just like in the old days. Even the laminated fastening of the bulkheads is so neatly executed that it did not have to be painted over.

The thing, construction number 145 - nothing more? Rolf Steckmest said at the time: "It's the biggest sailing boat we've ever built, so it's really something special. But I was more excited about the Scalar 34. I had designed it myself." He can only be honest.

Technical data "Gaudeamus II"

- Designer: Laurin/Nissen

- Torso length: 14,00 m

- Waterline length: 11,90 m

- Width:3,80 m

- Depth: 2,05 m

- Displacement: 14,6 t

- Ballast/proportion:6,5 t, 44 %

- Mainsail: 57,0 m²

- Furling genoa: 43,0 m²

- Furling genoa: 70,0 m²