In this article:

The spectacular images went around the world: a wooden schooner barque at the bottom of the Southern Ocean. The name "Endurance" on the curved oak planks at the stern. The ship of polar explorer Ernest Shackleton has been found! After 107 years at a depth of 3008 metres.

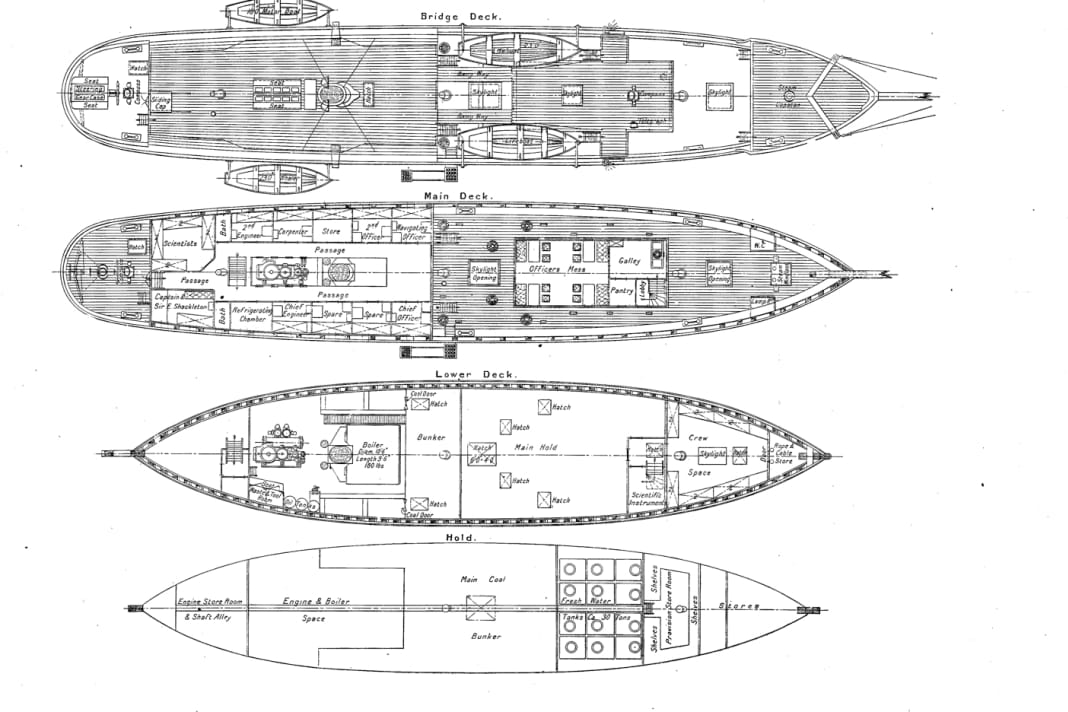

When the three-masted barque was launched in Norway on 17 December 1912, no one had any idea what awaited her and her crew. She was built for the harsh conditions in the Arctic Ocean: the almost 80-centimetre-thick hull made of solid oak was supported by 28-centimetre-thick frames. The steam engine inside her is designed to push her powerfully through the pack ice. "Polaris" is her name. Wealthy people were to travel comfortably with her on adventures, hunting and sightseeing in the Arctic. But when the "Polaris" floats, one of the owners is financially ruined.

The chronicle of the adventure

- 17 December 1912: The schooner barque "Polaris", later renamed "Endurance", is launched in Sandefjord, Norway

- 8 August 1914: The "Endurance" departs from Plymouth and travels to Antarctica via Argentina and South Georgia. Her destination: Vahsel Bay

- 18 January 1915: The "Endurance" is stuck in the ice in the Weddell Sea. She drifts 570 miles to the north-west in nine months

- 27 October 1915: The melting ice crushes the ship and it springs a leak. The crew disembarks and camps nearby

- 21 November 1915: The "Endurance" disappears under the ice and sinks. Captain Frank Worsley notes her last position

- 23 December 1915: On foot, the crew set off on the arduous journey northwards, the dinghies in tow

- 29 December 1915: The ice becomes insurmountable. The team waits in tents for three months on a drifting ice floe

- 9 April 1916: The ice floe breaks. In open boats, the men row and sail to Elephant Island in seven days

- 24 April 1916: Shackleton and five of his men set off in the dinghy "James Caird" to fetch help in South Georgia

- 10 May 1916: The "James Caird" reaches South Georgia. Shackleton walks across the island to the Husvik whaling station

- 30 August 1916: After three failed attempts, Shackleton succeeds in rescuing the 22 men on Elephant Island. All live

- 8 March 2022: The research team of the "Endurance22" expedition finds the wreck at a depth of 3008 metres in the Weddell Sea

Ernest Shackleton was at the start of an expedition in England at the same time. He had already been close to the South Pole twice, but never reached it. In the meantime Roald Amundsen with his "Fram" beat him to it. Shackleton had to set the bar higher: He now wants to be the first person to cross Antarctica on foot. Ever since his service in the merchant navy, he has been drawn to distant lands. He has no money at first; his last expedition ended with a pile of debt. The Royal Geographic Society provided him with a rather symbolic amount of money. Within a year, however, Shackleton managed to raise considerable sums for the expedition from private donors.

Endurance" project is set up

The "Polaris" is in no way inferior to the "Fram". He buys her far below her value and renames her "Endurance". "By endurance we conquer" is the motto of his Irish family. It is to be pushed to the limit during the journey. One of the dinghies is given the name of his biggest donor: James Caird.

He advertises his crew search: "Men wanted for dangerous voyage. Little pay, bitterly cold, long, cold months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success." Of the 5,000 or so applicants, 27 scientists and sailors ended up travelling on the "Endurance", including the excellent navigator Frank Worsley as captain.

The crew and more than 60 dogs are on board the "Endurance" when it sets sail from Plymouth on 8 August 1914. The voyage first takes them to Argentina. There, an 18-year-old stowaway, Perce Blackborow, sneaks on board. Shackleton was furious when he later discovered him on the high seas. However, he hires him as a steward on the condition that he will be the first to sacrifice himself if cannibalism is required. Blackborow agrees. An entry in the history books awaits him.

The last provisions are taken on board at the Grytviken whaling station in South Georgia. Coal for the engine is piled up on deck, a tonne of whale meat for the dogs hangs in large chunks in the rigging as the bow finally heads towards the South Pole.

The "Endurance" is encased in ice

The ship ploughs through areas of thin ice and fights its way through thicker ice. The inevitable collisions cause it to roar inside and the rigging to shake. Sometimes it has to make several attempts to break its way through the ice.

For weeks, the "Endurance" manoeuvres through the labyrinth of sea ice and icebergs, whipped by storms. Their destination is Vahsel Bay in the interior of the Weddell Sea. But the Antarctic summer leaves them before it has really begun. Just a day's journey away from the bay, a bone-chilling storm traps them in the ice.

For several weeks, the crew saws and hammers its way through thick chunks of ice to free it. When the weather is fine, the land is still visible on the distant horizon, as unreachable as the moon. "We'll have to wait for spring, which might bring us better luck," Shackleton finally realises in mid-February.

The last seals and birds disappear. Lonely as a ghost ship, the "Endurance" sits enthroned in the ice, its bowsprit pointed a few degrees towards the sky, its yards and shrouds thickly iced over and gleaming in the sun. In everyday life on board, the sea routine gives way to the land routine. The carpenter builds small cabins for the crew in the large mess room. They call their winter quarters the "Ritz" and settle in.

End of the polar ship

In May, the sun disappears behind the horizon, only its reflection in the refracting light occasionally sending it across the sky over the next four months. On a clear day, the moon shines as brightly as on a normal midday in warmer latitudes, but most of the time it is cold and dark. Storms pass over the "Endurance", icy and strong. But there is no gloomy mood.

The team passes the day with hockey and dog sled races, and the evening with songs and toasts to those at home. The scientists pursue their meteorological and biological studies. No mast is too high and no ice too smooth for Australian photographer Frank Hurley. With cameras the size of suitcases, several layers of stiff clothing and thick gloves on his cold fingers, he boards the yards for the perfect picture.

In October, the ice begins to melt. But it does not release the "Endurance", it attacks it. The engine is still running after eight months in the deep freeze, but there is no way out, the keel is too deep in the ice between grinding floes. Ice weighing tonnes builds up at its edges. Deafening noise keeps the men awake and on the alert, the ship jerks and sways. Huge blocks grow slowly upwards between the floes, bouncing like cherry stones between thumb and forefinger and landing with a crash on the ice.

The "Endurance" is no match for these forces. Her hull gives way. Water flows into the bilge and streams over the finely patterned and always well-kept parquet floor of the "Ritz". The fire in the cooker and lanterns goes out. The crew do their best, but in the end the water wins. As if with a final sigh, the three masts buckle one after the other. Yards, shrouds and sails spin tangled across the white. The crow's nest lands with a crash at the feet of photographer Frank Hurley, who continues filming undaunted.

Crew of the "Endurance" fights for survival

Shackleton and his men continue to salvage and clear the sinking ship. Entering their protective home in the long Antarctic winter is suddenly life-threatening. "Abandon ship!" - "Get off the ship" - is the last order on the "Endurance" on 27 October. For one more night, the electric light shines from the stern of the lonely barque until it is extinguished in the early morning by a particularly violent impact of the ice.

The crew waited in tents and watched the slow decay. Then, on 21 November, Shackleton's almost relieving call: "She's going, lads!" Captain Worsley notes: "There lay our poor ship a mile and a half away, fighting her death throes. Then she quickly submerged and the ice closed in." He notes the position of their sinking.

Shackleton has only one goal: to bring all the men home alive. They set off on foot on an exhausting journey, the massive wooden dinghies in tow. In the end, the ice becomes insurmountable and another camp is set up. Hardly any travelling group has ever made slower progress than the 28 men who bivouac in tents and whose floe drifts towards land at a snail's pace for more than three months. Hunger and wet clothes determine their days and icy nights, penguin after seal, seal after penguin their diet.

As the melting floe beneath the camp gradually cracks, Clarence Island and Elephant Island can already be seen on the horizon. Shackleton wants to try to reach Deception Island with the dinghies. There are supplies there for shipwrecked sailors and a small seafaring church. He reasoned that a seaworthy boat could be built from its timber.

Rescue to Elephant Island

The daring journey begins on 9 April. The tiny boats poke their way through the drifting ice to avoid drifting out into the open ocean. On the first night, the men are able to spend the night on an ice floe, after which they sit in their open boats day and night, defenceless against the storm and the cold. On the fourth day, a hazy sun allows a midday shot. The sobering positioning reveals: Among the bravely rowing men, the current has driven the boats 30 miles eastwards.

Deception Island is unreachable, Elephant Island their last chance. Suddenly, the boats are washed out of the pack ice into the open ocean. The crews set sail and set course for the island. Their lips chapped and eyelids red, their beards white from spray and frost, they endure day and night. Frostbite and thirst plague them. They chew raw seal meat and drink the blood, but the relief is short-lived. The situation is threatening.

On the sixth day, Elephant Island rises darkly out of the wild sea. But strong tidal currents and towering cliffs between steep glacier walls prevent them from falling ashore. The men have to spend another agonising night at sea, the land within their grasp, until they are finally able to head for a rocky beach on the seventh day.

The honour of the first landfall in history on Elephant Island is to belong to the youngest crew member: Perce Blackborow, the stowaway. Close to a coma and barely able to move, he tries to get off the ship. Shackleton impatiently pushes him over the edge. He sits there in the surf and doesn't move: he has frostbite on his feet and has to be pulled ashore by the crew. "It was a rather rough experience for Blackborow, but at least he can now say that he is the first man to sit on Elephant Island," writes Shackleton.

"Endurance" crew needs help from South Georgia

The men dance on the beach like at a party, letting gravel run through their fingers as if it were gold. Loud laughter bursts from their parched lips, blood runs down their faces: land beneath their feet after 497 days. There is water on the island and they can finally fire up the cooker for a hot meal: One of the most inhospitable places on the planet seems like paradise to them. It is to be their home for a long time to come, with no outside help to be expected. If they don't want to stay at this end of the world forever, they have to get help in South Georgia.

The "James Caird" is the largest and strongest dinghy. The ship's carpenter gives it a deck and a second mast. At the end of April, Shackleton promised the men remaining on Elephant Island that he would rescue them. They push and row the "James Caird" out into the surf for what is to become the greatest par force ride in sailing history.

Six men at just under seven metres, in a clammy boat with no comfortable place to sleep. Something is always constricting, pinching and squeezing in this cork that dances over metre-high waves. The crew share the limited space below deck with boulders. Sliding on their hands and knees, they have to keep shifting them from one side to the other to balance the weight. The spray freezes in the rigging and penetrates the deck.

"We fought against the sea and the wind and at the same time had to fight every day to stay alive," writes Shackleton. The knowledge that they were making distance kept them going. But often enough, they had to lie down in the snowstorm. Then their small boat is heaved onto foam-white wave crests and sails into the dark wave trough with flapping sails. Worsley navigates whenever the sun can be seen between the dark clouds. Just one degree off course and they miss South Georgia by ten miles. Beyond them, death lurks on the open ocean.

The unbelievable: Everyone survives

At midday on day 14, the cliffs of South Georgia shimmer through the low-hanging clouds. A safe place to land is not to be found in the early twilight. Mooring, waiting. Towards morning, the wind freshens rapidly into a hurricane. White foaming cross seas, wind that cuts the heads off the waves. The crew watch helplessly as the hurricane drives the "James Caird" further towards Legerwall. Until it suddenly turns in the evening and they can gain space. Finally, on 10 May, the small boat is washed through the eye of a needle, so narrow that the oars have to be retracted.

They are safe on land - but in the north-west and therefore on the wrong, deserted side of the island. They know about the Husvik whaling station in the east. There are people, ships and rescue there. After nine days, Shackleton and two of his men set off on a final, perilous march. Equipped only with the bare necessities, they fight their way through the unknown glaciers and mountains. After 36 hours of uninterrupted marching, the whaling station's steam whistle signals early in the morning that they have reached their destination. The rescue of the men left behind can begin.

Three attempts fail due to the mighty pack ice, but on 16 August the small Chilean steamship "Yelcho" reaches Elephant Island. All 22 men are alive. The rescue is considered one of the most heroic acts in maritime history. Shackleton was never to reach the South Pole: He died of a heart attack at the age of 47 in January 1922 in Grytviken - on an expedition ship bound for Antarctica.

Interview with Arved Fuchs

Polar explorer Arved Fuchs on the sinking of the "Endurance" and Shackleton's feat

Arved, how did you feel when the "Endurance" was found?

To be honest, I didn't believe that it would work. A ship like that doesn't sink like a stone, it sails under water too. When I saw the pictures of the stern with the lettering and the rudder, I was speechless.

She sank because the ice crushed her. What is it like when the ice shifts under the ship?

Ice pressings begin with a subtle singing sound as the pressure builds up under the ice. This is the overture to a loud concert. At some point, the pressure becomes so strong that the ice floes suddenly break up. Then the ice floes rumble and crash over each other like an earthquake. Woe betide anyone who gets in the way! We also experienced this with the "Dagmar Aaen". She is built in such a way that she is lifted out of the ice. But this is anything but a fun endeavour. That's the situation Shackleton was in back then.

Only with a different outcome. Why?

The "Endurance" was certainly the most stable ship on the market at the time, alongside Fridtjof Nansen's "Fram". She was sharply cut and a good sailor. Built for travelling in ice, she was not affected by ramming. But wintering in the ice did. She was not pushed out of the ice due to her frame shape. The ice pressure could hit her keel planks with full force and crush them.

Which stage was the most difficult for Shackleton after the sinking of the "Endurance"?

The journey to South Georgia has written sailing history. However, the leg in open boats to Elephant Island is always underestimated. They arrived there more dead than alive. When we sailed the route, we were in great shape and thought we could make it in three or four days. But there are currents that are not listed in any sailing manual. Huge icebergs sail towards you against the wind because of the underwater currents. That's very scary. It took us ten days and we were pretty flat when we arrived!

Technical data of the "Endurance"

- Type:Schooner bar

- Year of construction:1912

- Design engineer:Ole Aanderud Larsen

- Shipyard:Framnæs, Sandefjord, Norway

- Material:Greenheart wood, oak, fir

- Total length:43,80 m

- Width:7,60 m

- Weight:348 t

- Machine:Steam engine, 350 hp

- Max. speed:10.2 kn

Finding the "Endurance" in the video

This article first appeared in YACHT 09/2022 and has been updated for this online version.

This might also interest you:

- "Gjøa": Roald Amundsen's legendary expedition yacht

- "Fram": An expedition yacht with a great history

- "Wanderer III": A cruising yacht classic and the 96th degree of longitude

- Forgotten history: How a Bavarian builds a sailing boat and sails to India

- Portrait: Georg Dibbern makes history in German sailing

Ursula Meer

Redakteurin Panorama und Reise