Bone ships: The gruesome story behind the ship models made from animal bones

Marc Bielefeld

· 22.05.2023

The merchant's villa is located in a posh neighbourhood of Hamburg, a garden lines the house, an open staircase leads to the main entrance. Famous names have already walked in here, invited to dinners and dinner parties. On entering the premises, guests pass sculptures, maritime paintings and hand-picked antiques. In the parlour, however, there is an object that clearly stands out from the expected art categories. The work stands on a mahogany plinth, a glass display case protects it from dust, light and hasty fingers.

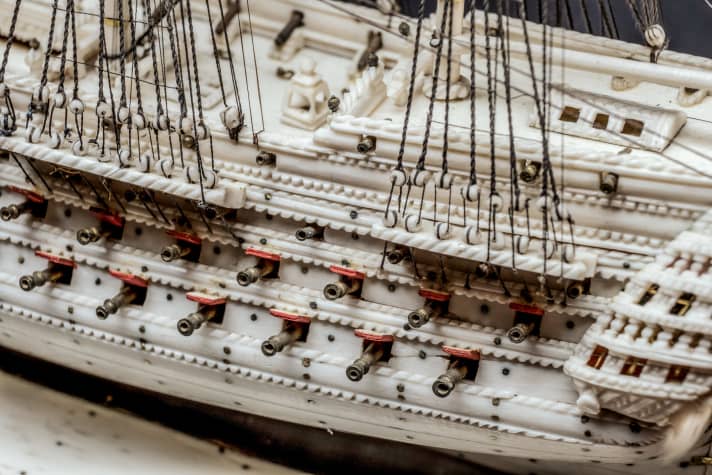

Your gaze falls on a chalk-white sailing ship that looks as if a thousand years of tropical sun have faded it forever. A three-master equipped with dozens of cannons that has absolutely nothing to do with the usual windowsill decorations. A ghost ship sits enthroned in front of the visitor, strangely under the skin. As if it had a forgotten, macabre story to tell.

The model, built in the early 19th century, is a meticulous reconstruction of a British Navy frigate. A two-decker of the third rank and second order, equipped with 78 guns and the "John Bull", a male figurehead. This rarity, whose value can hardly be estimated, is 40 centimetres long, 35 centimetres high and shows a typical "74". Originally, these ships had a length of 54 metres between the perpendiculars, they had two full-length battery decks, a mighty and steep bowsprit and full ship rigging. Over 200 years ago, frigates of this type sailed as flagships of the British fleet under none other than Lord Nelson. They had names such as "HMS Vanguard" or "HMS Elephant", fought the naval battle off the Egyptian harbour city of Abukir in 1798, were involved in the attack on Copenhagen in 1801 and, of course, at Trafalgar in 1805. And during the Napoleonic Wars, these ships were among the most sublime and feared apparitions of the seven seas.

Intricate details make the bone ships so admirable

The model's power lies above all in its unheard-of details and their perfection. After a few minutes of silent amazement, the viewer inevitably wonders: Which hands were able to recreate a ship so meticulously?

The model has filigree water stages, tiny blocks and the striking figurehead. A grimly forward-looking tar jacket with a red-brimmed hat, blue tailcoat and English shield, altogether just the size of a fingernail. The masts rise up almost snow-white, the yards spread out, while the rig looks like a tightly woven spider's web of wafer-thin breams, halyards, shrouds and guys. Ornate side galleries complete with cross-bows can be seen, tiny rivets on the planks. There are the galley funnels, stern davits and anchor spars. Even the fiddliest anchor buoys, hatch covers and water barrels are present, moulded with millimetre precision. There is no doubt that the model's greatness lies in its details. In the fanatical attention to the little things.

Created from animal bones and human hair

The businessman stands next to his piece of jewellery. He knows the history of the model inside out and is aware of every special feature of this rare object. "At the end of the day, it's the materials that make these ships so extraordinary," he explains. "The materials and the unspeakable living conditions under which these models were created."

We are talking about bone ships, built in dark dungeons and stinking prisons. Works of art, modelled without plans, without templates, purely from maritime memory. Marvellous works of art, created from what the prisoners had left in addition to old pieces of wood: animal bones and human hair.

The models are rare, and rare is the circle of collectors who chase after them

No, the Hamburg businessman would rather not say how many such ships he owns. The models are too rare, the small circle of gentlemen who collect maritime objects in this category and chase after the remaining bone ships in the world is too unknown. Just this much: "If another one turns up somewhere today, there's a stir in the scene, even if most of us don't even know each other."

Meanwhile, two books are on display on the large dining table in the lounge. They are specially written works that deal with the amazing history of the models. Volumes that delve deep into the details. Not just about the ships, but also about the incredible conditions under which the ominous bone replicas were once created.

Bone ships were made as barter goods

France had declared war on Austria and Prussia when fighting broke out on the European continent in April 1792. By 1815, countless people had lost their lives on land and at sea, and hundreds of thousands of prisoners ended up in British prisons. In some "depots", up to 8,000 prisoners of war lived in inhumane conditions. And yet some of the incarcerated men soon came up with the bold idea of making products in the midst of their torment that could be used as barter goods and sold on the prison markets. At first, the convicts wove simple straw mats and baskets, but soon grabbed knives and used sharpened nails to make ever finer artefacts with their bare hands. Small jewellery boxes, chess pieces, walking sticks and pipes were created, scratched, carved and filed from the material that was available to the poor devils: gnawed and boiled animal bones.

After all, meat was regularly served in the prison camps, mainly beef and mutton. What remained were plenty of bones, which were in demand as carving material - the raw material for ever more beautiful objects, which were created in the musty camps and brought in a few thalers at the markets, until one day bone ships appeared in prison camps such as Portchester Castle, Dartmoor, Liverpool and Norman Cross, alongside figures, caskets and decorated knobs, which had been modelled from memory by captured French sailors.

Various trades turn the bone ships into masterpieces

The fact that even the first of them were small masterpieces is certainly also due to the fact that the sailors must have included watchmakers, engravers, carpenters, turners and boat builders. Men of various trades who already had certain skills. In any case, the first buyers paid enough money for their works of art for the imprisoned sailors to continue carving and making new models. And soon the bone ships must have been the stars among the dungeon artworks. Because they became more and more refined and sophisticated until captains and shipowners asked for the bony beauties and were prepared to pay a lot of money for them.

Seafaring and war had brought forth a new art form: frigates, full-rigged ships and proud barges made of nothing but organic remains and human labour. They soon adorned not only the desks of professional sailors, but also those of admirals, wealthy brewers and merchants. Captains ordered the models and commissioned specific types. The British Admiralty later even hired 15 of the most skilful model makers who had made a name for themselves in the camps. The assignment: the talented prisoners were to recreate the famous "HMS Victory" - completely as a bone ship. The core was made from the original wood of the "Victory", and after the death of Lord Nelson, the proud model decorated his sarcophagus for 27 years.

But that was all over 200 years ago. Today, most of the legendary bone ships have long since sailed into oblivion. Over the decades and generations, the models gathered dust in attics, broke in the hands of unloving heirs or were simply disposed of by the ignorant. The already rare form of maritime art slowly disappeared - except for those exquisite examples that have survived and continue to fascinate collectors to this day. The remaining bone ships are treasures in their own right. Maritime feasts for the eyes with a historically significant background - and still many question marks in their wake.

Most of the bone ships can be seen in Hamburg

Manfred Stein, now 77 years old and probably the world's greatest expert on unusual ship models, is standing in front of the International Maritime Museum in Hamburg's Hafencity this morning. The qualified oceanographer has undertaken research trips to the North Sea, Greenland and Spitsbergen as a scientific director, and has travelled to the Antarctic Ocean, Canada and New Zealand. A man of the sea, he saw his first bone ship by chance in a museum in Halifax in 2003 - and was immediately fascinated.

After retiring, Stein researched the subject in depth. He became a volunteer at various museums and wrote his first book. The title: "Ships made of bone and human hair". Today, he is in contact with well-known auction houses such as Christie's and Sotheby's, and collectors call him to find out more about their own ships or potential new acquisitions. Nobody knows the collectors' scene as well as Manfred Stein.

"616 of the bone ships still exist in the world," he says. "Proven, as of today." 182 are in English museums, 47 in German museums. And 35 are owned by German private individuals. Stein says only this much: "When it comes to the number of bone ships in a city, Hamburg is the largest harbour in the world." However, discretion is desired among the insiders. The models are rare and expensive. Many would fetch tens of thousands of euros, some even six-figure sums - should they ever be sold.

The convicts used everything they could find and obtain

However, old ships also turn up from time to time, perhaps one or two a year. They are stored in cellars without some owners realising what they are holding. "The number of unreported cases is high," says Stein. "I would estimate that around 400 of them still exist somewhere in the world, unrecognised and possibly already badly damaged."

According to estimates, hundreds of valuable bone ships are still stored undiscovered in attics

There have been models on his workbench that were covered in red wine stains, bone ships that were completely dusty and worn out. Sometimes Stein is asked to restore the ships, as he is one of the few people to take on this delicate task. In order to restore the ships as perfectly as possible, Stein tries to recreate the unspeakable conditions that prevailed in the camps and on the prison ships at the time. To this end, he even made his own tools, cooked bones in his own kitchen and used only what was available to the maltreated sailors at the time.

Stein has recreated a tiny Archimedes drill with which microscopic holes can be drilled into the bones of cattle and pigs: wafer-thin, just millimetres in diameter. In this way, the convicts drilled through the tiniest cams and blocks. "They used the most primitive means to recreate the original ships, including their equipment." The convicts used everything they could find and obtain. Knives, needles, files, saws, adhesives, silk thread and bronze wire. Many sold their meat rations for it.

The most valuable bone ships have pulleys made of braided hair

First, the modellers carved the core, mostly from softwood. This created the hull from the underwater hull to the lower gun deck. This was then sanded and smoothed, the keel and stem were added and finally the planks made from thin mouldings. And these had to look as real as possible. The indented sailors sawed the bones into thin strips, sanded them to a mirror finish and used vinegar or lime paste to soften the bone planks for the mouldings. They drilled the rivet holes, then fixed the planks in place with bronze pins and finally glued them together - using bone glue left over from cleaning the leftover food in the kitchens. Their work was so seamless and accurate that in the end it looked as if the ship had been made from a single piece.

But the real details were yet to come. Masts, yards, yufferns, spars, capstans, steering wheels, rams, davits and rudders. Plus the dinghies, anchors and barrels that were carried on board the ships at the time. Some models even feature replicas of the outhouses on which the sailors used to sit outboard next to the bulwark, their legs dangling over the waves. In some cases, even the buckets that the bluejackets used in real life to scoop water out of the sea to wipe their bums have been reconstructed. And of course the cannons are also there, complete with drilled barrels and the running gun carriages on which they stood. On particularly valuable models, cables made of braided hair ran along the cannons and sometimes even the yards. When pulled, the cannons moved out, the yards were reefed and the ports could be opened and closed.

Months of work in groups of specialists

Incredible precision work, carried out in the grind of the dungeons. Ultimately, this was only possible because the prisoners had one thing in abundance in addition to all the hardships: Time. They often sat for months on a single model, even forming groups to work more efficiently. In the end, there were real specialists for the production of individual parts. Some carved figureheads, others the masts. Others were particularly good at weaving the smallest hammock nets or decorating the side galleries. And then there was the dirty work before the ships could even be built. Scraping the fat from the bones, scraping off blood and tissue before the bones could be cooked, cut and bleached.

It is also astonishing that the proportions of most of the bone ships are correct. Length, width, superstructures, dinghies, everything is just right.

The distinctive colour of the ships is still a mystery: the bright white of the bones, which has miraculously remained intact over the centuries. There are various theories about this. The most likely is that the sailors bleached the bones in sulphur dioxide. Sulphur was burnt to disinfect the latrines in the camps. The sulphur dioxide eventually formed a sulphurous acid with water, which was ideal for bleaching.

Aristotle Onassis collected bone ships

The fact that these precious art objects from the Neoclassical period are still so legendary and coveted today is also due to the colourful personalities who were always aware of the crazy history of the bone ships and tried to get their hands on them all over the world. One of the most famous of these was probably Aristotle Onassis. On his yacht "Christina" there were several of the white bone ships in display cases.

When he was still working in the shipping editorial department of the "Hamburger Abendblatt", Peter Tamm, the future founder of the International Maritime Museum and already Germany's most ardent collector of maritime artefacts and art, was on board the "Christina" one day. It was then that Onassis told him the almost forgotten story of the bone ships. Tamm senior looked at the display cases and was immediately infected. He then did his own research, went on the hunt and ended up with the largest collection of bone ships in Germany - now on display in the Museum am Hamburger Hafen.

Peter Tamm once said about the special appeal of the ships that it was extremely remarkable "how human destinies, combined with craftsmanship and popular design power, speak a language that touches the heart and mind in these ship models as a historical lesson".

Bone ships are "born in a storm"

A sentence that the Hamburg businessman would sign. He is still standing in front of his bone ship in his city villa and has now placed a second one on the large table, which he has carefully fetched from an adjoining room. A friend of his is visiting, also a collector of these old beauties. Most of the owners of these models still come from the "maritime corner", the two of them say. They include ship insurers, ship brokers, ship owners and captains. Entrepreneurs and managing directors who are professionally involved in seafaring. But no names are mentioned. Taboo.

The collectors do not see themselves as owners, but as custodians of witnesses to history

Perhaps this is also due to the fact that the owners of bone ships do not usually describe themselves as the owners of these treasures. "Ultimately, we are just custodians of these artefacts, guardians for posterity," say the two collectors. "The bone ships were created long before our time and, with good care, will still exist when we are all gone. We can just accompany them for a while."

These models are unique witnesses to history, manifestations of human intellectual and creative power in times of bitterest need. And perhaps, in the end, this is precisely the reason why the white ships are so mesmerising - they do not sail through the storm, they are born in the storm.