It is an inconspicuous paragraph in the cooperation agreement recently negotiated between the SPD and Green Party parliamentary groups - but it is nevertheless causing concern among sailors around the Kiel Fjord.

"In order to reduce the entry of microplastics and pollutants into the fjord as far as possible, we want to reduce the use of environmentally harmful antifouling paints for boats in municipal harbours," says the wording. However, it remains to be seen how these plans will be implemented.

YACHT therefore asked the Green councillor Dirk Scheelje for his opinion. This provides little of substance: "Kiel wants to develop into a marine conservation city. The Baltic Sea is the most polluted sea in the world. For these reasons, it is time to think about how we can prevent pollutants from entering the Baltic Sea as quickly as possible. The construction of a washing plant, as already successfully practised in Sweden, or the use of environmentally friendly paints for boats are possibilities. Everyone is called upon to make a contribution here."

The problem with antifouling is the copper

Copper, which is present in almost all biocide-containing paints, is considered to be the main problem with the ingress of pollutants from yachts. It reliably protects the hull against fouling by barnacles and mussels. However, the heavy metal also leaches out and enters the sea. How large the quantities released into the water are has been the subject of research for years.

For Germany, the study is based on research from 2018, which in turn refers to a study from 2012 that attempted to estimate the number of recreational craft based on the number of moorings and draw conclusions about the area of the underwater hull treated with antifouling. The study came to the conclusion that the antifouling of all recreational boats releases around 70 tonnes of heavy metal into the water every year, which corresponds to 19 percent of the total German input.

However, the authors also note that around 70 per cent of the pleasure craft fleet is based in inland areas. Around 43,000 moorings are assumed for the Baltic Sea, which corresponds to a fifth of the total fleet. However, as boat sizes vary both inland and offshore, it is not possible to draw any direct conclusions about the amount of copper discharged into the Baltic Sea.

In addition, neither the quantity of containers sold nor their exact composition is recorded in Germany, so the copper input determined in the study is based on many assumptions.

Antifoulings are not the only source of copper

According to a recent study by the European Union, around 1,560 tonnes of copper end up in the Baltic Sea every year, a good half of which is discharged into the sea via rivers. The metal is used in agriculture, for example, as a fungicide.

The second largest copper input comes from shipping, which is responsible for almost 37 per cent, with the focus here being on antifouling. Commercial shipping is said to release around 509 tonnes into the Baltic Sea. All pleasure craft together account for 59 tonnes, which corresponds to just under 3.8 percent of the annual copper load.

Therefore, no miracles can be expected from a restriction or ban on yacht paints containing copper. Nevertheless, every boat owner should think about whether the product currently in use is really necessary.

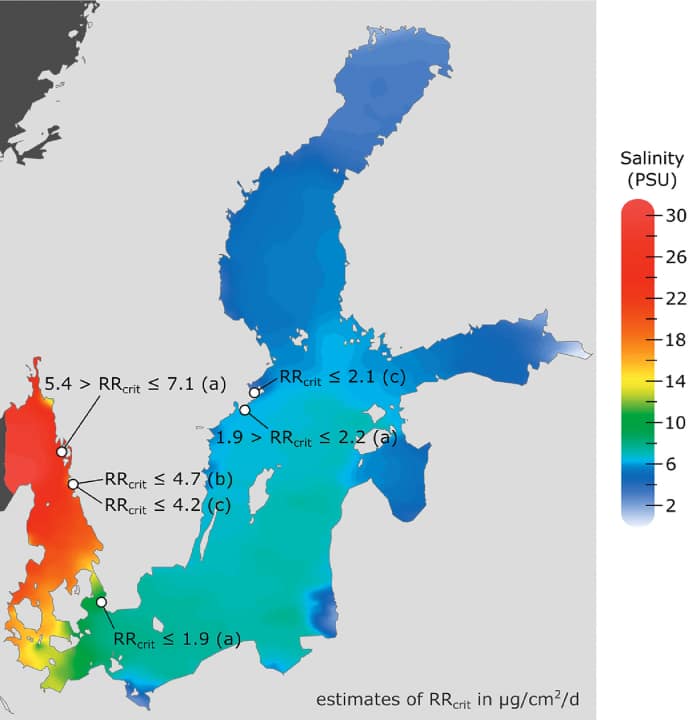

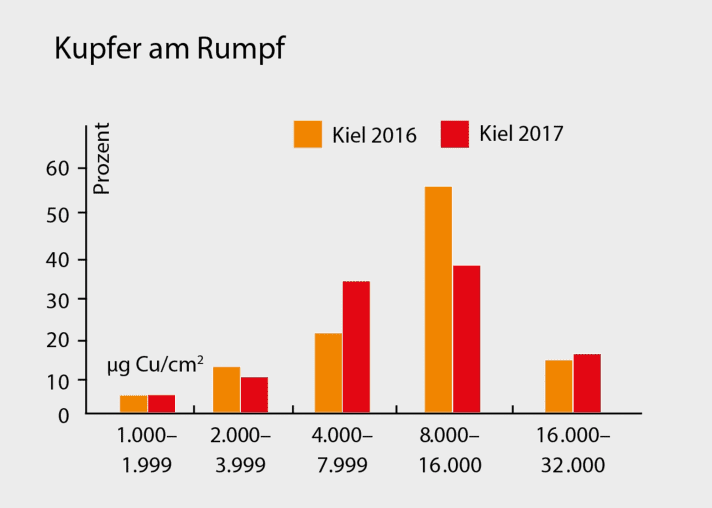

As a 2020 study funded by the Swedish Ministry of Transport shows, much more biocide often ends up in the water than is necessary to combat smallpox. The fouling pressure from macrofouling, i.e. smallpox and mussels, depends heavily on salinity. The authors have determined the correlation between salinity and necessary copper release. They assume that a release of less than eight micrograms per square centimetre per day would be necessary for the Belte and Sund and Kattegat sea areas. However, the recreational boat antifoulings investigated released up to 27.5 micrograms per square centimetre per day. Studies of antifouling paints in Kiel also came to similar conclusions.

One major problem with dosing is the large fluctuations in fouling pressure. Local influences such as nutrient input from land play just as much a role as changing water temperatures. Marine biologist Dr Burkard Watermann recently referred to this in a YACHT interview on the state of the Baltic Sea.

"In the past, it was normal for many smallpox patients to freeze to death in winter. That hardly happens any more. They survive in much larger numbers and can multiply again in the spring. As a result of rising water temperatures, we also increasingly have a situation where barnacles don't just start reproducing in spring. They often have a second phase in August or September. This used to be rare," says expert Watermann.

The situation was also observed this year; in early summer, the BSH pointed out that the water temperature in parts of the Baltic Sea was elevated. In line with this, the Swedish industry organisation Båtunionen reported a second wave of smallpox larvae in mid-August. In Sweden, the use of copper-containing paints has been restricted for years. In order to control the growth, the settlement periods are monitored with test panels. If fresh growth can be seen there, the underwater hull is cleaned before the pox really takes hold - that's the idea.

The crux of the second wave: the underwater hull is often already covered with a film of algae. Despite the copper-containing paint, this sometimes provides the pox larvae with a basis for settlement. It therefore becomes more difficult to keep the hull clean, even for coatings containing biocides.