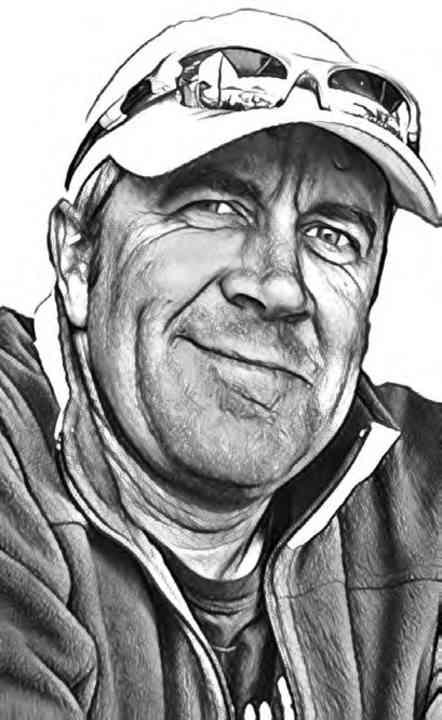

Series: Sailing practice with Tim Kröger

- Rig trim Correctly adjust the mast profile with shrouds and stays

- Sail trimGiving the sails the ideal profile on all courses

- Optimal crossing Sailing perfectly to windward with the right tactics

- Downwind sailing Cruising faster downwind with gennaker & co

Trimming the sails of a yacht continuously and optimally across all wind ranges on all courses is a demanding art. Two lessons learnt in advance: there is always room for improvement - and even small steps can significantly increase sailing pleasure.

Over the course of my career, I have worked with many sailmakers and international trimmer greats. What they all have in common is the irrepressible will to get the maximum performance out of the rig, sails and their own skills at all times.

Getting the maximum out of the sails requires enormous experience. The skill becomes visible when you sail with high-calibre people who are constantly working with the cloths at a high level. As the throttle pedals of their helmsmen, trimmers play a decisive role in the overall performance of a team. Because boats are steered with the sails in many conditions, it is clear that helmsmen have a hard time without good trimmers.

However, this short excursion into the professional world is only intended to help you understand the importance of good sail trim. In this instalment of my practical series, I would like to raise awareness of the topic and explain why some boats sail faster than others in different conditions, even though they are the same.

I covered this in the first episode of our series, what is important for rig trim and the associated possibilities for sailing the boat better. Once the rig is well trimmed in the boat, you can concentrate on the sails and their adjustment. And it doesn't matter whether new foil sails are used or somewhat older cloth.

Let's start at the front. The components that have the greatest influence on the headsails are the halyard tension and the centre of gravity positions as well as the sheet tension. Markings are essential for the ability to reproduce these settings. This is because on boats we are dealing with a constantly changing environment characterised by wind and waves. This simply requires a certain consistency, which makes it easier to orientate yourself.

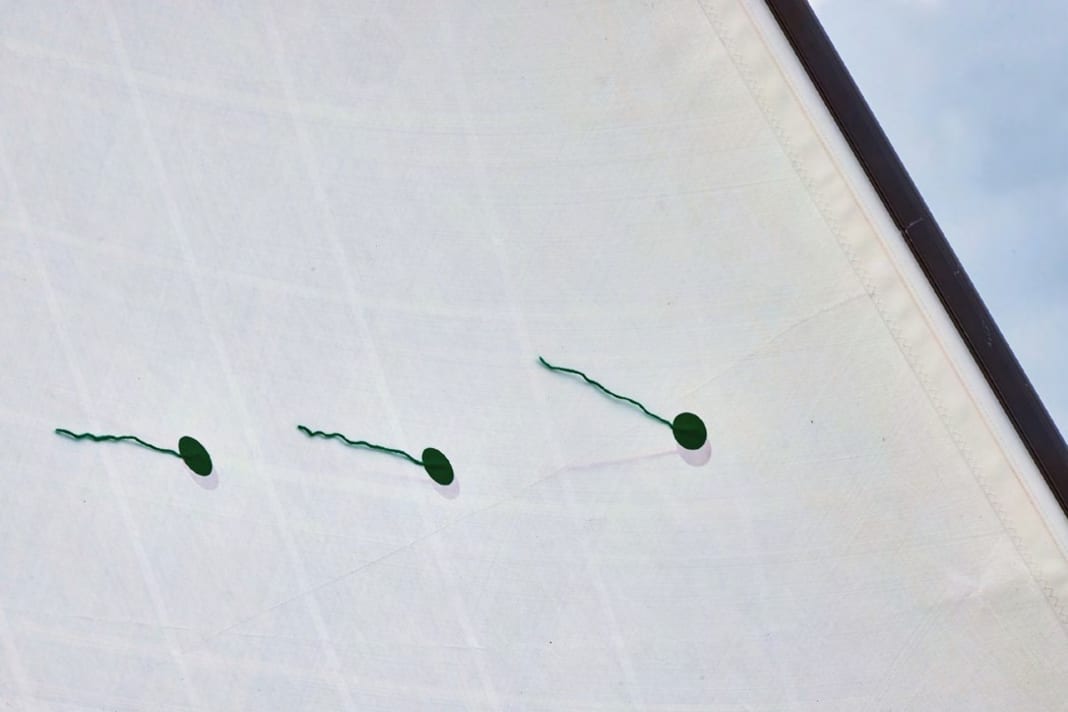

This consistency is achieved through markings. And preferably ones that do not fade or suddenly disappear. Felt pens or tap marks on traps are not bad, but usually only last for a short time. I have started to attach pom-poms made from rigging twine to the halyards or other trim lines. These often last longer than the rigging itself.

Helpful steps for sail trim

Having a maximum mark on a spinnaker halyard is already helpful for the person in the halyard cockpit when setting the sail. It saves having to look up or ask whether the sheet is fully set. It is similar with the tension on the headsail halyard: after each recovery, I can apply the same tension again the next time I set the sail in the same wind conditions. This is important because the halyard tension determines the profile of the sail and therefore its performance in the respective wind range.

With the headsail, it is also important that the hole points are in the correct position. This may well differ on different bows. For example, if the boat runs more acutely against the wave on one bow than on the other, a correspondingly different trim is required.

Apply markings to the running crop

A thin line from the forestay fitting can be used to check whether the hole points on both sides are symmetrical, i.e. in the same position. This is used to equalise the distance and marks can be set accordingly.

If the hole points are set with sliders on hole bars, it is possible to count the hole distances. If the centre points are to be adjusted with buoys, it is of course also possible to attach pusher marks to the adjusting buoy for the centre points. Ideally in different colours for any different sail sizes that are sheeted through the same carriage.

All of these optimisations are always about the reproducibility of the respective trim, so that it is possible to understand what I have set and under what conditions.

Wind threads on the luff necessary for sail trim

The wind lines on the luff and the leech lines are indispensable for controlling the sail trim. Without these aids, a trimmer is virtually blind, as they visualise the current that is applied to the sail.

The wind lines also help with steering, but above all with the optimum adjustment of the sails on all courses - it is hardly possible without them.

I've sailed with mainsail trimmers who realised after setting the mainsail that the upper thread had torn off, so the cloth had to be recovered just before the start to glue on a new one. The timing up to the start became hectic, but the more effective and therefore better trimmed mainsail was more than just an equaliser.

Marks on the wheel can also help to trim the sails better and bring the boat to its optimum limits. The trim of the sails can induce too much or too little rudder pressure.

Markings on sails, hole points and steering

As mentioned at the beginning, sail trim is a complex art and fills entire books. This is not the place to go into it in depth, but rather to sharpen the sailor's eye in order to avoid the most serious mistakes. After all, even those who are primarily concerned with sailing safely from A to B, and not with constantly speeding through the area, do not want to sail towards self-destruction with flapping sails. Sensible and well-trimmed sails say thank you by lasting longer.

Interim conclusion: The most important aids for good sail trim are the wind lines, which are useful in all wind conditions. Then there is the halyard tension, which I keep an eye on with the help of my markers, the sheet tension and the position of the hole points or the traveller.

The boom vang, kicker or vang is only used to a limited extent on upwind courses. On a ship with a traveller, it is only tightened slightly on upwind courses, only "warm to the touch". The boom vang only takes over control of the leech tension of the mainsail when you drop and furl the mainsheet.

However, there are exceptions when it comes to boom vang and therefore special remarks should be made: Many modern yachts no longer have a tackle as a mainsheet, but only a fixed point on the cockpit floor - without a traveller - where the mainsheet is deflected and then goes onto winches. Or it's like on a Swan 60, which I sailed on for a few years, where there is only a passage in the cockpit floor through which the mainsheet disappears and is then tightened and furled below deck using a hydraulic cylinder.

With a mainsheet guide like this, the boom vang takes on an overriding role, as you cannot actually control the leech tension of the mainsail with the sheet due to the lack of a traveller, especially if the mainsheet is slightly feathered. So the boom vang becomes an extended mainsheet.

In order to get the main boom on the Swan 60 to the midships line when sailing upwind, we used an extra tackle to pull the boom end to windward. Of course, this tacking line had to be unhooked from the bulwark or a fixed point on the windward rail and hooked onto the new windward side at every tack.

This may sound a little adventurous to implement, but such aids can optimise the performance of many a cruising yacht that has a similar mainsheet system.

Trim settings on upwind courses

The photos show the different trim settings on upwind courses for easier understanding only in lighter winds, because the aim is simply to sharpen the eye for avoidable gross mistakes and to develop the fun of developing further on this basis in all wind conditions.

In light winds, the sail is trimmed carefully. The halyard tension on the headsail is set so that the cross-folds are pulled out of the luff. The rule here is: the newer my sail is, the more cautiously I use the halyard tension. A sail is subject to a natural ageing process. The older it gets, the more the profile depth moves backwards. To compensate for this process and still achieve a reasonably good profile, I have to tighten the halyard more. Of course, this is only possible up to a certain point. If this point is reached one day, the only thing that helps is a call to your trusted sailmaker.

I work in a similar way with the mainsail, although many boats have an upper measurement mark on the mast beyond which the sail must not be hoisted. This is especially true for regattas. And a Wednesday regatta is one of them.

For cloths that are a little older, the classic cunningham is used - the thimble on the luff above the throat fitting. The cunningham gives me the opportunity to move the profile depth of the sail further forwards. The same applies here: old sails require a little more attention and tension, especially when the wind picks up a little. With new sails and especially with new foil sails, it is sufficient to set the halyard to the mark for the time being.

And while we're on the subject of the mainsail: The foot naturally also has an influence on the profile depth and the shape of the sail. There is also a maximum mark at the end of the main boom beyond which the cloth must not be pulled out.

In flatter winds, the foot is only set slightly on upwind courses, just enough to create a satisfactory profile depth. If the foot is too loose in light winds, the profile will be too deep, which will not generate effective propulsion, and if the foot is too tight, the sail will be trimmed too flat and you will not make rapid progress.

Trimming is primarily about getting closer to the optimum shape of the sail design, especially when it is new. If, on the other hand, the sail cloth is already a little tired, the trimming elements need to be worked a little harder to create the desired shape.

Sail design is also an art form in our sport. Detailed comments on this for all wind ranges would go beyond the scope of this article. Basically, new sails should always have the optimum shape of a wing. Ideally, the profile depth should be matched to the boat.

Sailing with optimum twist in the mainsail

The rule of thumb here is that modern racing yachts tend to need flatter profiles, while heavy yachts tend to need deeper profiles in order to generate power. In this respect, the sailmaker can certainly offer the right advice to ensure that a new sail fits the boat perfectly. This applies equally to mainsails and headsails.

However, it is not only the halyard tension that is decisive for the headsail. The hoist point and the sheet tension also have a huge influence on the trim and especially on the twist, i.e. the twisting of the sail in the upper area. A headsail that is tightly hoisted and therefore completely closed in the leech will not be able to accelerate the ship.

When looking into the sail, the trimmer should always have the upper leech line in view. If it blows out, the twist is basically set correctly via the sheet tension and the hoist point. If the sheet is now taken a little tighter, the thread starts to blow to windward. At this moment, the sail is furled a little again until the thread blows out again.

The twist control works in the same way for the mainsail. Here, too, the eye is focussed on the uppermost thread: The right twist is achieved when the thread always dances behind the leech between blowing out and disappearing.

The position of the main boom should be on the midship line, on some boats you can also pull the traveller to windward in light winds until the end of the boom is slightly above the midship line. However, this changes immediately when a wave comes up. Then the traveller belongs more to leeward to build up more speed. However, these rules of thumb are just as little set in stone as the constantly changing conditions and wind forces that we have to deal with when sailing. The images opposite were taken in light winds and are intended to illustrate the visible differences between extremely poor and correct trim for precisely these conditions.

When reacting to changing conditions, the trimmer must carefully observe the sail and constantly readjust it so that the lines remain in position. The helmsman also concentrates on the lines on the luff in order to steer the boat at the optimum height on the wind. Only when there is smooth communication between the helmsman, main trimmer and luff trimmer, as in regatta sailing, will the yacht sail optimally.

Good and bad examples of sail trim

It can also happen that the headsail trimmer is satisfied with his profile and the boat sails at a good upwind angle, but the twist results in such strong downwinds from the headsail that the mainsail trimmer has to take the sheet tighter and the helmsman gets more rudder pressure as a result. In such situations, coordination is required.

More twist in the headsail gives more air for the mainsail and results in less pressure on the rudder. This results in higher speed and ultimately more height upwind.

Rig has an influence on the position of the sails

As the rig also has a big influence on the position of the sails and the backstay is used as a trim element on most yachts, a simple rule of thumb applies here to start with. In light winds, I set the backstay only slightly or almost not at all. This leads to more slack in the forestay and the headsail becomes a little fuller. The mast then also has little bend and the mainsail has correspondingly more profile depth.

If the wind picks up, the backstay or, on older IOR boats, the backstay is tightened. The forestay sag is reduced and the mast is bent more, resulting in a flatter mainsail profile. Finally, it is also advisable to take a look along the mast groove downwind to check that the mast is still straight and that the diagonals have enough tension.

Sail trim is a huge, almost infinite field of activity in which you can let off steam depending on your disposition and desire. I would like to encourage everyone to get to grips with it more. Because better sail trim also means: more control over the boat, more optimised and faster sailing as well as more protection and therefore a longer service life for the material.

In my opinion, these are all good reasons to take a closer look at the trim. It may be challenging in some areas, but it is worthwhile in many cases and leads to more sailing pleasure on the water and on land.