Over in the USA, they enjoy almost cult status and sometimes bring huge fields with superstar line-ups to the starting lines of many regattas. Here in Europe, on the other hand, hardly anyone knows them: the American scows. For mysterious reasons, the ultra-flat and fast flounders have never really made the leap across the pond.

Read more about "Scow":

Scows in their present form already existed at the turn of the century before last, designed by J. O. Johnson, a Norwegian who emigrated to America. Based on his ideas, he built a boat which, thanks to its extremely flattened shape and flat nose, was supposed to glide over the waves rather than through them. The boat also had to be as light as possible, so it was fitted with centreboards rather than a keel. The 38-foot-long "Minnezitka" became the forerunner of today's A-Scows, the impressive, almost twelve-metre-long racing boats that are chased around the race courses at breathtaking speeds by crews of up to eight people.

Built only at Melges

However, because they were bulky, expensive and difficult to sail, the concept of the A-Scows was scaled down over the years. The E-Scows, which are over three metres shorter and have almost identical hull and rig shapes, are no less spectacular than their big sisters, but remain easier to handle and are only sailed by three or four people for regattas. This is why the small Scow class has been able to develop more quickly into a more widespread standardised class in America. The leading and now only manufacturer of these scows is Melges Performance Sailboats in Zenda in the US state of Wisconsin.

One of the few E-Scows that has found its way to Europe is located in Switzerland, on Lake Neuchâtel. The ship was imported only recently and its design corresponds to the latest development generation. The A and E class boats have only been built with a retractable bowsprit for a large top gennaker since 2008 following corresponding rule changes. Until then, the scows were powered by symmetrical spinnakers.

The colourful cloth is set using a single-line system from a so-called "launcher", a hole in the foredeck. This means that the halyard and the line for pulling out the bowsprit are linked. All you need to do is pull a single line to set the sail; the same applies when retrieving it. The sail is furled in a kind of channel that runs right through the centre of the long cockpit. This mighty tunnel not only serves as a kind of recovery tube for the gennaker, but also acts as a robustly built strongback to ensure that the extremely flat structures of the scow are stiff enough.

However, because the owners of the test boat rarely take part in regattas and are usually only travelling in pairs, they had the sailmaker tailor a reacher half the size instead of the standard gennaker, which measures more than 50 square metres. The limited sail area is sufficient for the test conditions on Lake Neuchâtel with 15 knots of wind. The flat and light E-Scow immediately starts planing and literally jumps over the short waves with its flattened hull - almost like stones when ditching. The GPS log constantly shows double-digit values. Record on the test day: 13.8 knots, and that with the small gennaker and an inexperienced and light crew.

Waves - better not

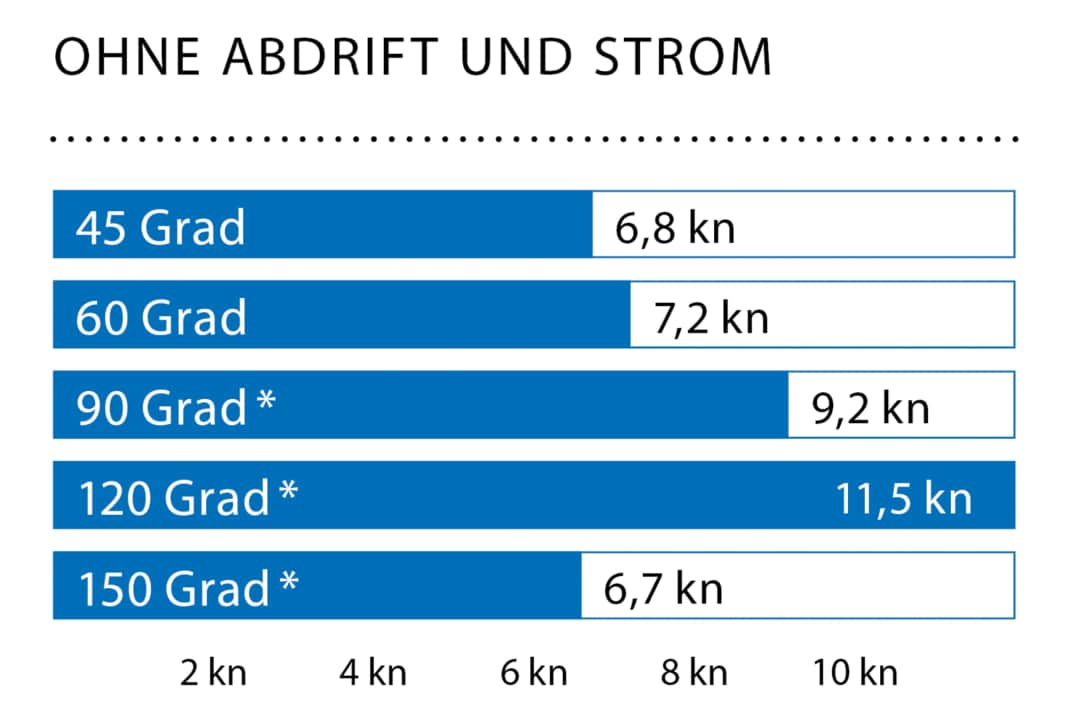

Hard upwind, the E-Scow also gets going very well; the flounder reaches 6.8 knots at an angle of 45 degrees to the true wind. With a full crew and the appropriate expertise for the extremely demanding sail trim, it would undoubtedly be possible to tease out even more tenths of a knot.

Further out on the lake, however, the scow has to fight against increasingly high waves. With brute force, the flat bow without a point hammers through the choppy water and gives the crew hanging high up in the foot straps a constant shower. Generally speaking, scows don't like waves and are therefore usually sailed on inland lakes or sheltered bays in the USA.

Measured values of the Melges E-Scow

And they can also capsize. In principle, this type of boat is nothing more than a large dinghy; it has no keel, but two centreboards on the chine, which are raised and lowered alternately during manoeuvres. The greatest risk of capsizing is that the very long main boom drags through the water and "hangs on" when manoeuvring on a room sheet course; continuous work with the boom vang is therefore essential. In the event that an E-Scow capsizes anyway, buoyancy aids can be used, which are simply zipped into the head of the mainsail in windy conditions. They prevent capsizing and allow the crew to right the scow under their own steam.

To keep the keelless boat's sail pressure point as low as possible, the aluminium rig is comparatively short and the sail plan is compact. The mast is therefore easy to set and lower by hand. E-scows are not usually stored in harbour boxes, but on the trailer or on suitable boat trolleys on land and are lowered in and out of the water for use via the ramp. Thanks to the ready-to-sail total weight of just 440 kilograms, the retractable centreboards and the two small stub rudders at the stern, slipping and transport by road are extremely simple and uncomplicated.

Price of the Melges E-Scow

An E-Scow ex-shipyard in the USA costs 98,500 US dollars, which is around 90,270 euros net at the current exchange rate. If German VAT is added, the gross price is 107,420 euros. The scope of delivery includes a set of sails with main, jib and gennaker. Additional costs are incurred for freight from overseas to Europe.

- Base price ex shipyard: 107,420 € incl. 19 % VAT.

As of 03/2025, how the prices shown are defined, read here!

YACHT review of the Melges E-Scow

E-scows are still little known in Europe - which is surprising, as the flat-bottomed flounders from the USA are ideal for use on inland waterways. And with their high performance potential, they have a good chance of winning.

Design and concept

Lightweight, trailerable and slipable

High-quality workmanship

Consistent regatta boat

Not capsize-proof

Low distribution

Sailing performance and trim

Fast on all courses

Perfect trimming facilities

Active sailing, like a dinghy

Equipment and technology

Recovery channel for the gennaker

High-quality equipment ex shipyard

No motorisation planned

The Melges E-Scow in detail

Technical data of the Melges E-Scow

- Design engineer: Melges

- CE design category: D

- Torso length: 8,53 m

- Width: 2,06 m

- Draught (centreboards): 1,40 m

- Weight: 438 kg

- Mainsail: 21,2 m²

- Fock: 8,8 m²

- Gennaker: 51,1 m²

Hull and deck construction

GRP sandwich construction with foam core and epoxy resin. Built using the vacuum infusion process. Solid strongback for structural reinforcement

Shipyard and direct sales

Melges Performance Sailboats; Zenda, Wisconsin 53195 (USA); www.melges.com

This test was first published in 2019 and has been revised for the online version.

Michael Good

Editor Test & Technology

Michael Good is test editor at YACHT and is primarily responsible for new boats, their presentation and the production of test reports. Michael Good lives and works in Switzerland on the shores of Lake Constance. He has been sailing since childhood and, in addition to his professional activities, has also been an active regatta sailor for many years, currently mainly in the Finn Dinghy and Melges 24 classes. He is also co-owner of a 45 National Cruiser built in 1917. Michael Good has been working for the YACHT editorial team since January 2005 and has tested around 500 yachts, catamarans and dinghies in that time.