There are not many standard boatyards that state the difference in weight compared to the standard boat in their price list for optional extras. And even fewer list even low single-digit deviations with accounting precision, as JPK does.

For example, those who order the mast for the new 1050 in even higher-quality carbon fibre than the Axxon profile, which is already laminated with high-modulus fibres, can save five kilograms for the additional cost of 3,700 euros. If you choose the boom in carbon instead of aluminium, you will lighten your boat by eight kilos and your bank account by 5,300 euros. The cheapest option is to switch from the standard Yanmar diesel with Saildrive to the 20 hp Lombardini with shaft drive: minus 25 kilos, plus 2,740 euros. However, as shipyard boss Jean-Pierre Kelbert freely admits, it then rattles a lot more.

More from the shipyard:

Weight, or rather the avoidance of it, has always been one of the virtues of the shipyard, which is highly successful in ocean racing. The company, which is located opposite Lorient, virtually in the Mecca of the French offshore elite and was only known to those familiar with the scene 15 years ago, has always had a penchant for asceticism. With its latest design, however, JPK has taken it to the extreme.

If you look at the overall displacement, the 1050 does not appear to be extremely light: the 34-foot-long racer weighs 3,480 kilograms. However, 44 per cent or 1,520 kilograms of this is in the keel, an unusually high figure. In addition, the fin, which has a lead bomb at the end for the first time in a long time, is very low at 2.22 metres. This lowers the centre of gravity and increases rigidity - one of the reasons why the boat can carry a lot of sail area.

If you deduct the ballast, the JPK weighs less than two tonnes including rigging, fittings and fittings. By comparison, her predecessor, the equally successful 1030, came in at 2.2 tonnes - despite her far less voluminous hull.

Measured values of the JPK 1050

In fact, the differences are far greater than the figures suggest. Because the 1050 is the decidedly more extreme, more modern, more consistent design. "We had developed two basic variants at the beginning of the design phase," says Jean-Pierre Kelbert: "one that was more evolutionary and one that clearly departed from our previous philosophy." Both were drawn by the famous Jacques Valer, one of the last architects who still put their designs on paper by hand, rather than using a CAD programme on a computer. JPK chose the revolutionary path. And anyone who has sailed them knows that it was the right decision.

"In principle, it's a small Class 40," is how the shipyard boss characterises it. That characterises it pretty well, even if the lines are less radical. However, the 1050 is more than a mere reference to the so-called scow-bow design with a flat-bow-like foredeck. It looks incredibly beefy, especially from the front. Her waterline starts a good metre and a half behind the stem (see p. 97) and remains particularly narrow overall. Aft, the hull is very flat, with a slightly concave shape in the last third to enable early planing and minimise drag.

JPK 1050 is a revelation

At first and second glance, the JPK looks like a sister to the IRC racing yacht "Lann Ael 3" developed by Sam Manuard and is also very similar to the Pogo RC derived from it, down to a few construction parameters, also a Manuard design. Jean-Pierre Kelbert leaves no doubt as to where the inspiration for the 1050 came from. "I think everyone studied 'Lann Ael' closely because it was so competitive right from the start, despite its high IRC racing value."

In addition to him and Jacques Valer, Jean-Baptiste Dejeanty was also involved in the development of the 1050, responsible for design at JPK and a designer himself. He came from CDK, a shipyard specialising in high-end boats, where Boris Herrmann is currently having his new boat built. "JB", as he is known to everyone, started in the Mini-Transat in 2003 with a prototype he designed himself, switched to the Imoca class in 2005 and started in the Vendée Globe in 2008. His preference for light, fast offshore racers has significantly influenced the 1050, which is why it is far more than a derivative. It is a revelation.

The JPK 1050 under sail

During the test off Port Ginesta in Spain, she had to prove herself in a wide weather window as part of Europe's Yacht of the Year in mid-October. It ranged from a flat 5 knots of wind to a sporty 25 knots, occasionally even 30 knots in gusts, coupled with a steep, sometimes confused sea. There were only a few nominees who conveyed anywhere near as much sheer enthusiasm.

From the very first moment, it is as if she is embracing you like an old friend: there is an immediate intuitive trust. In the cockpit, which is littered with tangled ropes and may seem overwhelming at first glance, you quickly get your bearings at the tiller boom. Seating position, overview, line guidance: almost perfect.

The mainsail is sheeted by coarse and fine adjustment via a central console, the traveller line is directly at hand on the coaming, the backstay runs on a winch aft of the helmsman, and the genoa can be folded to windward - all within easy reach. It is a layout that has been perfected and proven over several model generations, to which ultimately only the backstay guide has been added, because the JPK 1050 carries a wide, flared main from the yard and because the mast, which has only one pair of spreaders, needs to be guided aft when the 125-square-metre A2 is also pulling on the beam or the Code Zero, which measures almost 50 square metres in light winds.

Everything fits under sail

When in position, the crew can enjoy a footrest mounted in the centre of the cockpit, which is high enough to ensure good support. Further aft, there is a GRP bracket on both sides, but it is positioned a little too close to the coaming. Tall helmsmen can therefore not relax with their legs almost outstretched, but have to support their weight with their thighs. For this reason, the shipyard offers optional fold-down U-shaped brackets, the height of which can be individually adjusted. Apart from that, everything is fine, apart from the somewhat high operating forces of the main bulkhead buoy. If you leave the sheet unreefed in 16 to 18 knots of wind, hauling tight becomes a sport of strength even with the fine adjustment.

The JPK can still fully carry the main even at the cross. This is made possible by the range of stability already mentioned at the beginning, which stems from the high ballast ratio on the one hand and the shape of the frame on the other. As slim as the waterline of the 1050 is in the neutral position, the dimensional stability increases just as quickly when heeled.

Probably no-one would think of taking off unreefed at 5 Beaufort for a trial run. But Jean-Pierre Kelbert knows his latest model inside out and only nods briefly in response to enquiring glances in the direction of the rig. So full sail.

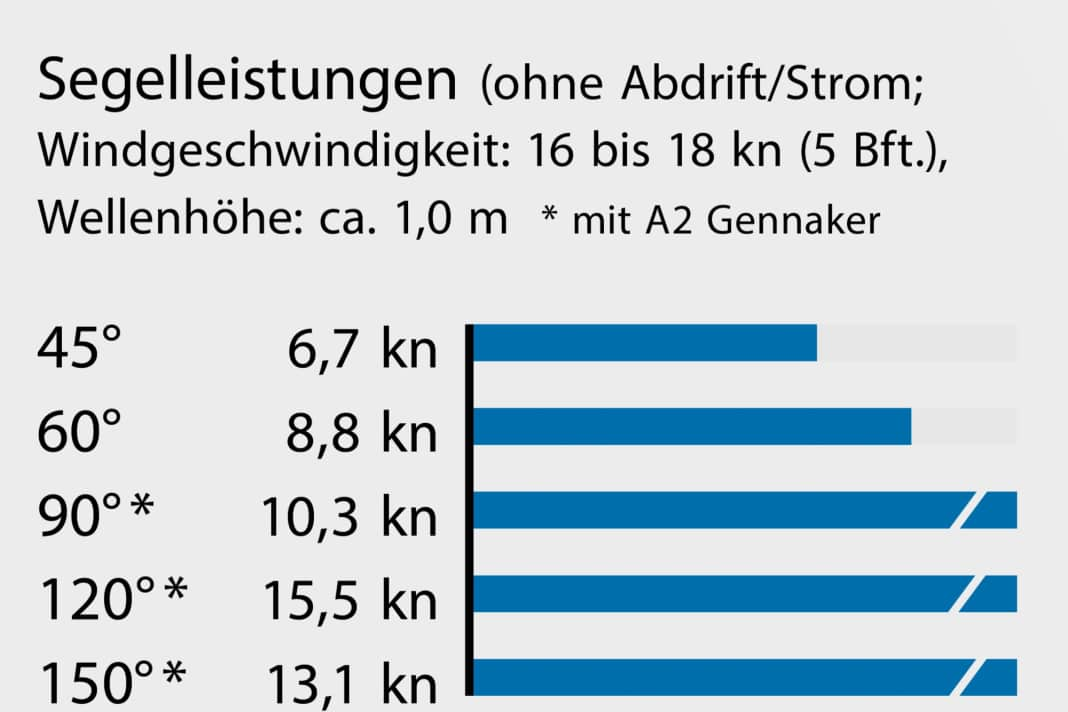

On the wind, the stiffness is particularly surprising. With a slightly deflected traveller, the main can be close-hauled without the JPK becoming too luffy. She marches upwind at around 7 knots, with a very respectable tacking angle of around 90 degrees for the wave pattern. Because she is relatively light, she goes over the seas more than through them and therefore remains quite dry. However, she requires concentration, because five degrees too high noticeably slows her down, five degrees too low reduces her speed to windward too much.

Mixture of maximum agility and superior stability

After a few tacks, the yardmaster hoists the large gennaker on the forecastle. In gusts, the anemometer now shows 22, 23 knots. Wouldn't the smaller A5 do? It still measures 102 square metres, which is actually enough for these conditions. But as soon as the white A2 is up, it becomes clear that the bold choice was the right one. Before the mighty bladder is properly trimmed, the 1050 is already jumping like a greyhound chasing prey: 12 knots, 13, 14 ... Practically from a standing start and under autopilot, which has no difficulty whatsoever with the increase in power.

With the right sheet tension, an average speed of 15 knots is possible on the mainsheet, continuously and effortlessly, and even 18, 19 or 20 knots at the top. At the same time, the boat can be brought up to 110 degrees upwind for a short time to gain momentum without running out of control. It is precisely this mixture of maximum agility and superior stability that sets the JPK 1050 so clearly above its competitors. It makes it easy to enter spheres that until recently were reserved for trimarans at best.

It is not her only favourite discipline. She is equally impressive on open upwind courses, where she remains almost unrivalled. At 60 to 70 degrees to the true wind, the water at the transom breaks smoothly at 3 to 4 Beaufort. At force 5 she glides along at 9 to 10 knots. Sailing in the wow range.

The nonchalance with which she does this, this not having to force herself, is perhaps the most astonishing thing. It wasn't like this from the start - it did require a bit of fine-tuning. For example, the shipyard went through several sizes of rudder bearings to ensure that the profiles would not fold up unintentionally. JPK also enlarged the blades themselves at the beginning of the season. They are now almost 1.50 metres deep - one of the reasons for the impressive balance and controllability.

Below deck of the JPK 1050

Do we still need to talk about berth and gap dimensions, cabin layout and cruising comfort? Not really, because this is a regatta boat where everything is subordinate to performance. So just this much: it really isn't the 1050's strong point.

You have to crawl into the depths of the aft compartments, if you want to call them that, in order to find space on a narrow double berth or a tubular frame at best. More space is available forward, but only if the toilet is moved aft, which in turn restricts the space there.

Features and prices of the JPK 1050

Nevertheless, the shipyard offers other, more cruising-friendly variants on request. By dispensing with the single seat next to the pantry block on the port side, additional storage space and a cool box can be installed there. Swallow's nests in the saloon and a much larger table are also possible, all made from lightweight GRP with a laminated foam core. A shower is even possible on the port aft side. Heating is also available at extra cost. However, even in cruising trim, the JPK remains first and foremost a thoroughbred sailing machine.

Unfortunately, she is also expensive. Equipped ready to sail, you could order two First 30s for the same money, which have similar hull lines, a more cosy interior and also considerable potential. But that's a bit like comparing a Golf R with a Porsche 911 Carrera GTS: both fascinatingly fast, both top in their own way - and yet not really in the same league.

- Base price ex shipyard: 267.600 €

- Price ready to sail: 304.140 €

- Comfort price: 324.370 €

- Guarantee/against osmosis: 5/10 years

As of 2025, as the prices shown are defined, you will find here!

The JPK 1050 undoubtedly represents the pinnacle of development in the series construction of monohull ocean-going yachts on this side of the 35-foot mark. This is also reflected in the IRC results lists, which the French yacht tops as the most successful new development. Jean-Pierre Kelbert, who triumphed with her in the Spi Ouest and two-handed in the Rolex Fastnet Race itself in the overall standings, even threw overboard his resolution not to sail a transatlantic regatta at the age of 60 because of her. "Never again!", he had already vowed in 2024. Now he has signed up after all. In April, he will be taking part in the Cap Martinique regatta with the 1050, single-handed to boot. Why? "It's just so much fun to sail this boat!"

YACHT rating of the JPK 1050

With the 1050, JPK has established a new era in ocean racing. No other yacht currently offers more speed potential and controllability. A yacht to die for!

Design and concept

State-of-the-art hull design

Low displacement

Very high price

Sailing performance and trim

Glides on very early

Lies perfectly on the rudder

Almost perfect deck layout

/(-) Many trim/control lines

Living and finishing quality

/(-) Lightweight, minimalist interior

Tight berth dimensions

No headroom fore and aft

Equipment and technology

Very high-quality fittings

Elaborate GRP construction

High degree of customisability

The JPK 1050 in detail

Technical data of the JPK 1050

- Design engineer: Jacques Valer

- CE design category: A

- Torso length: 10,444 m

- Total length: 12,15 m

- Waterline length: 8,10 m

- Width: 3,54 m

- Depth: 2,22 m

- Mast height above WL: 16,26 m

- Theor. torso speed: 6.9 kn

- Weight: 3,480 kg

- Ballast/proportion: 1.520 t/44 %

- Mainsail: 42,0 m2

- Furling genoa (106 %): 31,0 m²

- machine (Yanmar): 15 kW/21 hp

- Fuel tank: 40 l

- Fresh water tank: 80 l

- Holding tank: 40 l

Hull and deck construction

Sandwich construction with Airex foam core, vacuum laminated with vinyl ester resin. Keel bomb made of lead, fin made of cast iron in GS specification.

Expansion options

Although it is designed as a regatta yacht, JPK also offers the 1050 with a double berth aft, WC/shower, heating and cool box for an additional 4000 euros.

Weight optimisation

The boat is already very light as standard. However, with a carbon boom, Lombardini diesel, rod rigging and other measures, a good 50 kilos can be saved.

Sailing wardrobe

A complete set of membrane racing sails costs around 50,000 euros. But you can have a lot of fun with a main, genoa, code zero and A2 gennaker for as little as 20,000 euros.

Shipyard

1, Boulevard Lavoisier, 56260 Larmor-Plage, France, Tel. 0033/297 83 89 07, www.jpk.fr

Distribution

Direct sale ex shipyard

Flat nose, steep flanks

There are several reasons for the JPK's leap in performance. The most significant lies in its lines. The hull looks rather clumsy.

Something has fundamentally changed in the design of modern racing yachts and performance cruisers. The JPK 1050 is currently the best example of this turning point, which actually began four years ago with the IRC racing yacht "Lann Ael 3" developed by Sam Manuard. Since then, it has influenced more and more boats.

The most visible characteristic of the successful formula is undoubtedly the wide foredeck section, first trialled more than ten years ago in the Mini-650 class, later in the Class 40 and the Imoca 60 - at least as far as offshore use is concerned. Originally, the idea of the flat bow came from the US dinghy type A Scow, first built in 1901, which also gave the design principle its name.

The advantage is not so much, as one might think, in the additional volume and the resulting greater lift on rough courses, which reduces undercutting of the hull. That is just one aspect.

In fact, boats designed in this way also benefit enormously in half winds because they have more dimensional stability and the more symmetrical lines of the underwater hull contribute less to trim in the wind. The transition to the stern and its design is also crucial, which is why it took several development steps to give scow bow boats, whose strengths still lie on deeper courses, acceptable all-round characteristics.

The JPK has a slightly concave hull shape in the last third in order to be able to break away from its own wave pattern early on and minimise drag, which increases exponentially with speed. This is also the reason for the flow-optimised GRP skeg around the drive shaft and the small fins in front of the attached rudder blades, which are intended to prevent the formation of vortices.

It takes a lot of structure to build such full-bodied, fast yachts

Due to the small wetted surface area, it sails surprisingly agile even in light winds, which seems to contradict its compact appearance. However, it always needs a bit of leech to extend the waterline in this way - which is why special sails such as Code Zero or Jib Top are indispensable on the wind to get it going.

It also takes experience and sensitivity to really drive her over the course according to her rating. As easy as she makes it to go very fast and as error-friendly as she is, which simplifies operation under autopilot, it is difficult to get the last five per cent out of her. "In the Fastnet Race," says Jean-Pierre Kelbert, "we steered almost the entire distance by hand, apart from manoeuvres and sail changes."

It is not easy to build such full-bodied, fast yachts. It takes a lot of structure to make the surfaces rigid enough to withstand heavy seas at high speeds. And this structure must not torpedo the endeavour to achieve the lowest possible displacement. The frames of the JPK therefore extend almost in a ring in the foredeck right down to below deck, which reduces the possible berth width by a good fifteen centimetres.

Now that they have cracked the code for scows in Larmor-Plage, they are already thinking ahead. Shipyard boss Kelbert can imagine developing a cruising offshoot around 35 feet - with more comfort and moderate performance, but in principle very similar sailing characteristics. The demand for such a JPK 35 Fast Cruiser is likely to be enormous. With this and comparable boats such as the somewhat more conventional First 30, a new generation of performance cruisers could become established in the coming years.

ADVERTISEMENT

Insure your JPK 1050 from 1,832.46 euros per year* - third party liability and comprehensive cover. Many options available: Protect your crew with passenger accident insurance. Simply calculate and take out online: yachting24.de

* Offer from Yachting24 valid for a sum insured of 268,000 euros (with current value cover), excess: 1,500 euros, liability cover: 8 million euros.