- Wood was the material of choice right from the start

- The motto when designing the Woy 26: "Keep it simple"

- "Bio-Based Boats": Vacuum infusion process for wood

- The Woy 26 lies more on the water than in it

- Trimming is done solely via kicker, sheet and stretcher

- Sailing fun comes first

- Technical data Woy 26

On display in Hall 15, Stand C21

Martin Menzner had just moored his J/80 in Kiel-Schilksee, jetty 2, when he was approached by a young man who introduced himself as Jan Brügge, a master boat builder from Grödersby near Arnis on the Schlei. Menzner, who is not only a successful regatta sailor specialising in sports boats, but also a designer of special sailing yachts, primarily made of wood and aluminium, with his company Berckemeyer Yacht Design, had designed a daysailer a few years previously. It had caught Bruges' eye and had given him a bold idea. It was the beautiful and unique LA 28 made of moulded plywood. "I wanted to build a classic. Something like the Dragon, but modern." While some boat builders are now thinking about retiring, Brügge was already thinking about what kind of boat he could still be building in 30 years' time. That was the spark for Menzner. He immediately agreed to design this boat.

Wood was the material of choice right from the start

That was five years ago, both of them can still remember this first meeting very well, and so the Woy 26 project began. "Woy" is a construct of a name from the English "Wooden Yacht". It was clear from the outset that wood was the material of choice. And more than that. The boat was to be sustainable by completely avoiding tropical woods. Brügge only wanted to use light-coloured local wood species and as little plastic as possible.

I wanted to build a classic, something like the dragon, but in a modern version."

A modern boat, an eye-catcher that attracts attention on the jetty. The boat should be really fast, but still easy to sail. If possible, even single-handed. Turbos such as hydrofoils or a tilting keel were ruled out from the outset. Both for weight and cost reasons. "And we wanted our boat to be safe to sail without a helmet," adds Martin Menzner with a view to modern, high-performance sailing technology such as foils and wing masts. All in all, a very ambitious and clearly defined project.

The motto when designing the Woy 26: "Keep it simple"

Initial sketches were drawn and then discarded. Gradually, Menzner and Brügge reduced the design further and further. Deck superstructures disappeared, as did trimming devices such as travellers and backstays. "Keep it simple" was the motto. This went back and forth for over a year until the boat builder was able to take the first piece of wood into his hands.

He is very familiar with this material. Brügge learnt his trade at the Stapelfeldt yacht and boatyard in Kappeln, Grauhöft, where he played a key role in the construction of the Judel/Vrolijk design "Tango", a fast daysailer. In 2016, Brügge set up his own business and founded the shipyard just outside Arnis.

Since then, they have been repairing and refitting whatever customers want. In GRP too, of course, but the boatbuilders' hearts beat for wood. With the courage to go big, they set to work. In July 2022, the first complete new build was pulled out of the hall, the highly acclaimed 48-foot sailing yacht "Elida". A cruiser/racer, built according to the owner's wishes. The hull is made of form-glued spruce, but with an ultra-modern carbon fibre structure, finished with a final layer of dark mahogany for a sophisticated look.

"Bio-Based Boats": Vacuum infusion process for wood

And now the handy, purist Woy with its new approach to materials, construction and sustainability. Brügge was also helped by the experience he gained from building the "Tango". However, its hull was still built using conventional, tried-and-tested wooden boat construction methods. The veneers are glued on in layers, with four to five layers glued together with epoxy. The hull is then wrapped in a plastic film, under which a vacuum is created to provide the necessary contact pressure. It is almost impossible to avoid the boat builders coming into contact with the resin again and again, which can lead to health problems.

There has long been a process in GRP boatbuilding in which the resin is injected into the dry fibreglass fabrics. However, this has not yet been used for wooden boats. But Brügge wanted such a vacuum infusion process for his new build. That's why he teamed up with the University for Sustainable Development in Eberswalde. In a joint research project, they developed a process that was ultimately used for the first time in the construction of the Woy 26. Four layers of wood veneer, each 2.5 millimetres thick, were glued together in this way. They call the project Bio-Based Boats, and it even won a sustainability award, which honours innovative ideas, concepts and projects from Schleswig-Holstein every two years.

The Woy 26 lies more on the water than in it

However, it took another three and a half years until completion. Customer orders always took priority, so the self-financed Woy project often had to wait. But now it is finished, the result is clearly visible floating on the glistening waters of the Schlei and shining in the sun: the prototype, construction number 1, in Sunrise Orange. Other colours are of course possible. It's a film, not paint, and it sticks to planks of light-coloured, almost white Allgäu spruce wood.

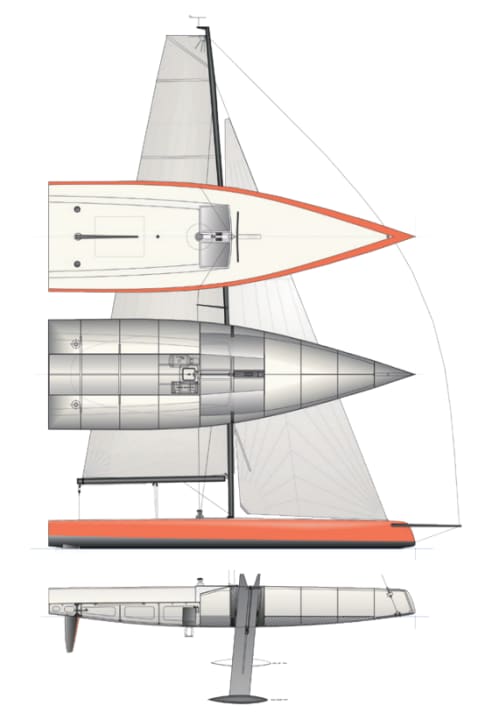

The side view is also unusual in other respects. A high waterline creates the impression that the boat lies more on the water than in it. The edge of the deck has a barely noticeable positive leap and the bow with the long bowsprit is inclined aft as a wave piercer. The boat operates with two rudder blades, which are not mounted on the outside of the wide, flat transom, but under the stern. It all looks damn fast, even from the jetty. "We wanted a daysailer, but the result is more of a dayracer," says Brügge with a grin.

The hull merges seamlessly into the deck in an elegant curve. It's a delight to the touch, you want to stroke it immediately. There's not a single step or edge to disturb where the hull shell merges into the stave deck. This is made of Oregon pine, also known as Douglas fir. The tree originally comes from North America, but has long been grown in European forests. The wood is very hard and durable, making it ideal for boat building. The sticks are five millimetres thick and are glued along the entire length of the cockpit thwarts, the floor and the foredeck.

Annual rings, so dense that you can hardly count them

The elegant impression is completed when you look at the sloping surfaces in the cockpit. A silver fir veneer with annual rings so dense that you can hardly count them. The console behind the mast, on which a single winch stands as the central trimming device, has also been visually refined in this way.

On either side of this console are two companionway hatches, manholes through which you can get below deck. This is not the end of the Woy's fine workmanship, on the contrary. The furling system for the foresail is easily accessible at the very front. In front of it, across the entire width of the boat, there is a flat area about 2.4 metres long, upholstered with a soft, water-repellent special mattress and illuminated by LED strips along the stringers under the ceiling. A real double berth, not bad for a day racer. Smooth, warm spruce wood on the left and right. A solid frame bulkhead, also made of spruce, and evenly spaced bulkheads made of larch plywood.

Lifting keel with crank operation

This is also where the only hull element made of carbon fibre-reinforced plastic, the keel box, is hidden. After all, it has to be able to take a beating, especially if a lifting keel is installed later on, with which the draught of the 344-kilogram lead bomb can be reduced from 1.9 to 1.1 metres. This will then work hydraulically at the touch of a button. It is planned that the keel can be fixed in two positions for sailing. Once at 1.9 metres and then at around 1.4 to 1.5 metres for inland areas with shallow water or anchoring close to the shore. In this version, the keel is operated using a hand crank.

Another clever idea is a large lid in the cockpit floor that can be lifted off completely. This ensures comfort. If you want to stay on board for a while while moored, you can put your feet down here. Above all, however, the yacht's energy centre, the on-board batteries and the Momentum electric motor are located here amidships. The shaft and propeller of the drive are located in a box, where they disappear when the yacht is sailing. They are only extended downwards out of the hull when required.

Trimming is done solely via kicker, sheet and stretcher

On this unusual hull, eight metres long, 2.42 metres wide and weighing 1,120 kilograms, stands an eleven metre long carbon fibre mast from Pauger in Hungary with only one pair of spreaders, on which the heavily flared mainsail and the self-tacking jib, both 3Di raw membranes from North Sails, and, if required, a 70 square metre gennaker can be used.

The carbon mast is held in place by solid stainless steel rod shrouds. There are no backstays and no backstay, their functions are replaced by strongly swept spreaders and more upper shroud tension. The sail is trimmed using the kicker, sheet and stretcher alone. The foot block for the mainsheet sits at the top of a cockpit, for which an adjustment option is still being worked on. There is no reefing option for the mainsail.

Menzner and Brügge stand on the jetty and look out over the water a little sceptically. The plan for today was actually another trial run, with a bit of wind if you like. But is that really necessary with 5 to 6 Beaufort and gusts of up to 30 knots? The desire for action wins out. And curiosity. How will the new build handle in these conditions? A third co-sailor comes on board, after a few minutes the sails are up and the Woy roars off. What comes next looks pretty sporty.

Sailing fun comes first

The gusts rattle out of nowhere from the cover of the forest on the shore near Rabelsund. Menzner on the tiller and Brügge on the mainsheet have their work cut out for them. Full concentration to avoid heeling the boat excessively. Again and again, the helmsman luffs up to the wind edge. The tacks go off without a hitch, and the lugging log exceeds the ten-knot mark several times. Last time, they had set the gennaker in force 4 winds. They prefer not to do that today. But they are happy as they are. The boat is light and stable on the rudder on all courses. Even when the windward rudder blade comes completely out of the water, there is no unsafe feeling.

If the boat is accepted by the market, a 35-foot-long derivative of the same design is to follow, but then not as a naked daysailer

Various further test runs will follow. A few details are still to be changed or improved, but in principle the boat builder and designer are more than satisfied with their latest baby. "Easy handling, sailing fun is the top priority. The concept will prove itself," they are certain. As soon as customer orders are received, the Woy will go into series production. Jan Brügge estimates it will take six months to build each boat. And he is already dreaming of having laid the foundations for a new standardised class with the prototype. He is also already thinking about a Woy 35, which would no longer be a daysailer, but a weekender. And a very special one at that.

Technical data Woy 26

- Length hull/waterline: 8,00/7,13 m

- Width: 2,42 m

- Depth: 1,10-1,90 m

- Weight/ballast: 1,12/0,36 t

- Main/jib/gennaker: 21/14/70 m2

- Sail carrying capacity: 5.7 (dimensionless)

Christian Irrgang

Freier Autor