The harbour berth holders rub their eyes in amazement: a small boat with a yellow junk-style sail projecting far out over the foredeck silently approaches the entrance to a marina on the Kiel Fjord. Without any engine noise, it glides up to the jetty in a light breeze, then the only sail before the wind drops down accurately in one go as if by magic. The crew and their boat immediately become the main topic of conversation in the harbour: what on earth is that? A mast that is far too thick, too far forward and not even stowed! A bright yellow awning as a sail, held up by thick aluminium tubes as battens! Such a thing can't possibly sail properly - it contradicts all the visual habits of a halfway nautically socialised person!

Other special boats:

Paul Schnabel and his companion Antonia "Toni" Grubert are the creators of this blockbuster at the harbour cinema. "We are greeted with amazement and curiosity in every harbour, including sceptical looks," explains Paul. "A rig like this polarises people in areas where a Bermuda rig is standard." The pair have made a habit of placing a leaflet about the boat and the rig on the jetty in the harbour - so they can satisfy the curiosity of onlookers without constantly explaining the concept themselves.

After years of research, the decision to rerig is made

It all started very conservatively: the owner couple bought the classic fibreglass Maxi 77, built in 1978, for around 4,500 euros and christened it "Ilvy". They previously owned a Beneteau Evasion 32 DS deck saloon yacht, but found it too unwieldy, labour-intensive and expensive to maintain.

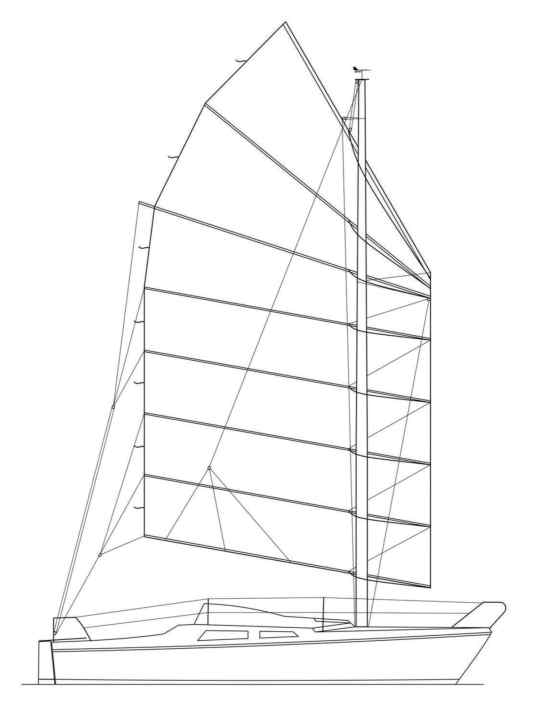

They wanted a daysailer for the Kiel Fjord - because it was too difficult for them to give up cruising altogether. The Maxi 77 seemed to be the ideal compromise, but Paul could never get used to the Bermuda rig. He has long been fascinated by the rig designs of junks. As a shipbuilding and mechanical engineer specialising in aerodynamics and hydrodynamics, he combines personal interest with professional expertise. "The simplicity of this rig appeals to me: an unstayed mast with a very forward pressure point, no headsail and a mainsail that is easy to handle and quick and easy to reef thanks to large battens and sewn-in pockets," explains the 34-year-old. "This provides a lot of safety for the crew and the sailing characteristics need not be inferior to those of a conventional rig," says Paul.

He spent six years researching, corresponding and tinkering with it. A lively exchange takes place on the web platform of the British Junk Rig Association, where enthusiasts from all over the world promote the further development of the junk rig.

"The intervention in the deck structure and the interior design of the yacht is the most complex part, but it is also feasible for self-builders."

The junk sail first made its way from Asia to sea-going western yachts in the 1960s and 1970s. Pioneers in this field were the British rigging specialists Hasler and McLeod, the authors of Practical Junk Rig - now the classic on the subject of junk sails for yachts. Herbert "Blondie" Hasler in particular made the junk rig famous after he successfully took part in the Ostar transatlantic race with his converted folk boat "Jester".

Initially, these sails had poor upwind performance. The negative image has remained, although development has continued at a rapid pace. "The am-wind performance has increased significantly over the years and now equals that of a Bermudarigg," says Paul, explaining the development.

A junk rig for the Maxi 77

He himself started quite rustic with an aluminium lamppost - a blank for a street lamp. Round and conical in shape, it proved to be the perfect pole. Paul cut an opening in the deck and reinforced its structure. "The intervention in the deck structure and the interior design of the yacht is the most complex part, but it is also feasible for self-builders," explains Paul. The mast is unsupported - and thus acts like a vibration compensator that dampens the movement of the boat. Incoming gusts are cushioned as the mast gives way and the sail top opens. Its position is significantly further forward than with a stay-stepped mast, as the new sail is balanced far in front of the mast. After a test phase to find the optimum position, the mast was finally wedged.

The fully battened lugger sail is made from inexpensive, UV-resistant awning fabric. Paul believes he can dispense with the use of higher-quality fabric such as Dacron or even low-stretch laminate because of the lower forces involved. Sturdy battens made of aluminium tubes divide the sail into several panels. Short sheets are connected to the mainsheet via pulleys so that the force absorbed by each individual batten is redirected into the sheet - the sailcloth itself is relieved.

What initially sounds like a tangle of lines is surprisingly simple in practice: only a single sheet needs to be guided in the cockpit. The sail is reinforced with webbing at the luff and leech, but there is neither a downhaul nor a luff or leech stretcher. The weight of the sail battens ensures that the sail falls down. Only one halyard, the sheet and two trim lines are used. The latter move the sail forwards or backwards along the mast so that the pressure point can be fine-tuned - either further towards the bow or aft to control windward and leeward leeway. There is no need for winches, as the forces generated remain moderate thanks to the tackle and the pre-balanced sail. However, the system requires long sheets and halyards.

"I built the rig in this version for just under 3,000 euros and invested around 250 hours of labour," the shipbuilding expert calculates. "The pulley blocks were the most expensive purchase." To make the fabric, the self-made sailmaker sat in the attic of his Kiel flat in sub-zero temperatures and sewed the awning fabric into the right panels and pockets.

Functional and simple in all areas

The concept of simplicity and the philosophy of sustainability run like a red thread through this ambitious project - even inside the boat. The conversion focussed on practicality, simplicity and variability. "Functional and simple," summarises Toni. "Modular systems create free space - hardly anything is permanently installed so that it can be used flexibly in different places." Instead of cupboards, she developed a flexible storage system made of nets and boxes. The 32-year-old utilised her manual skills in a targeted manner: All sea valves were removed and sealed, panels were stripped of old adhesive residue, sanded and painted. Mattresses were made from seaweed for the foredeck. Battery-powered LED clamp lamps were used as lighting, which can be used anywhere on board - exactly where they are needed.

The forward position of the mast creates significantly more space in the saloon. The original saloon table, which was previously fixed to the mast support, has been replaced by a versatile table that now serves as a dining table, work table and cockpit table. Two lockers were removed in the foredeck to create a suitable berth for the two-metre tall Paul. Due to its design, a forecastle already offers a lot of space for a boat that is almost eight metres long - but the conversion not only makes "Ilvy" feel more spacious, it actually makes it more spacious.

The galley is functionally equipped: a paraffin cooker and a sink are sufficient, there is no refrigerator. Water is supplied from canisters with a capacity of up to 100 litres, which are stowed in the lockers. A dry toilet transforms the saloon into a quiet place to go if necessary.

Being self-sufficient and not having to constantly check the battery charge is important to the two sailors. Mobile solar panels provide enough power to charge electronic devices such as laptops for work and iPads for navigation, so they can easily manage 14 days without harbour infrastructure on their trips.

"We've never been so relaxed on a cruise"

Professionally familiar with tools for a structured way of working, the two owners approached the planning and realisation of their project professionally. After around 700 hours of work and material costs of around 2,000 euros, the renovation and interior remodelling were completed. Their aim was to use as little material as possible, utilise existing materials and minimise the purchase of new equipment. With a second-hand maxi, an inexpensive and effective rig that makes the engine largely superfluous and a reduced, modular interior, the owners are steering an alternative course: "We get our lines, accessories and oilskins from where the fishermen shop."

"Whether cruising in the archipelago or along the coast, we were always on the move and felt safe at all times"

Paul took a year and a half off work for this project and the subsequent cruise, while Toni reduced her working hours. The refit, the conversion and the trips are documented in the blog fiery-sails.com and documented on Instagram - the interest is great and the dialogue lively.

After a successful 14-day test voyage in the western Baltic Sea and the Schlei in early summer 2024, they sailed on through Denmark to Sweden and back to Kiel. In total, they travelled for six months and logged over 1,500 nautical miles. "We've never been so relaxed on a cruise before," the pair enthuse about the sailing characteristics of their design. "Whether we were cruising between the archipelago or on long trips along the coast - we were travelling fast and felt very safe at all times." For Paul, this is mainly due to the single sails, the good tacking angle, the low centre of gravity even when sailing upwind and the easy, quick reduction of the sail area. "Before difficult, narrow passages, we simply reduced the speed briefly by reefing, then reefed out again in no time at all and continued," says Paul.

Maxi with eye-catching junk rig goes down well

The sail is operated entirely from the cockpit, and all crew operations can be carried out from here. "We never - really never - had to go forwards to the mast or on deck when sailing." Due to the change in power transmission and the reduced heel, sailing with the maxi junk feels like the boat is ten feet longer. It sits quietly on the rudder, does not develop much pressure and even a little wind is enough to give the light, small yacht a good ride.

Antonia and Paul will never forget the astonished looks on the faces of the crews on larger yachts when the little Maxi with its striking, large yellow junk rig comes up from astern and overtakes them. They often give each other the thumbs up, applaud and exchange addresses so that photos can be sent back and forth later. A date for a drink together in the harbour is not uncommon.

The appearance of the "Ilvy" with its bright yellow sail is usually a minor sensation, but Paul's conversion of the rig is no gimmick. After the test phase and proving his worth in cruising, the enormous potential of the junk rig has once again been confirmed for him.

"Before difficult, narrow passages, we reduced the speed by reefing, then reefed out again and continued."

His conclusion: "This option can be applied to almost any type of boat." Either convert used yachts or, better still, "design a new type of hull that utilises the full potential of this rig". This is because, in addition to the favourable handling characteristics, the mast positioned further forward creates a noticeable gain in space in the saloon - which makes it possible to change the entire layout. The harbour berth holders in Kiel can therefore look forward to seeing what will soon be arriving in their harbour.

"Ilvy" in detail

Technical data of the "Ilvy"

- Length: 7,70 m

- Width: 2,64 m

- Weight: approx. 2.0 tonnes

- Depth: 1,45 m

- Mast length: 10,70 m

- Width of the panels: Bottom 1 x 4.9 m; top 1.9 x 4.9 m (triangular)

- Lugger sails: 35,0 m²

The basis: the GRP classic Maxi 77

A stable and fast boat from Sweden that is also suitable for longer journeys. Built between 1972 and 1984, it is still widely used today and is popular as an inexpensive, flexible boat. The forecastle offers a surprising amount of space below deck for its size. The market price for a ready-to-sail Maxi 77 is currently between 2,000 and 7,000 euros.

The junk rig - construction & advantages

The modern interpretation of the junk rig is based on an unstayed mast, which is inserted about one metre further forward through the deck than on a Bermuda-rigged yacht. Compared to conventional rigs, the mast is only slightly larger in diameter. The fully battened lugger sail remains hoisted at all times and is designed for all wind conditions. The sail surface is pre-balanced and passes far in front of the mast, reducing the load on the sheets. Traditionally, the sail is set on the port side and secured to the mast in this position with straps. On the starboard bow, the sail is then automatically attached to the mast.

The 35 square metre sail area is divided into several panels by sturdy battens made of aluminium tubes or wood. The numerous battens are each connected to the mainsheet via short sheets and pulleys. This means that the force absorbed by each individual batten is transferred directly to the sheet, which greatly reduces the load on the sailcloth.

Material & aerodynamics

As the sailcloth is less stressed, it can be made of a lighter, less stretchy and cheaper material - such as tarpaulin or awning fabric. These materials are also more UV-resistant than classic Dacron, making the use of a tarpaulin unnecessary. In contrast to older junk rig designs, a fixed belly is now sewn into each individual panel between the battens. In order to maintain the optimum sail shape when reefing, the upper panels have a flatter profile, while the lower panels have more volume, as they are the first to be reefed in strong winds.

Handling & manoeuvrability

The sail falls downwards solely due to the weight of the battens and then lies neatly together, almost fluffed up. The tension on the luff and leech is also only created by the rig's own weight.

The only lines required are: a halyard, a sheet, two trim lines to fine-tune the windward and leeward leeway and towing lines to secure the reefed or folded sail bundle. Sheet winches are not required as the forces generated remain moderate due to the pre-balancing.

With the junk rig, the Maxi 77 achieves a tacking angle of around 90 degrees according to the compass, a value that is also common for normally rigged yachts. Thanks to the unstayed mast, the sail can even be opened more than 90 degrees before the wind, should this be necessary due to the course.