"Oh look, a bark! How beautiful." Sighing, a couple have stopped in front of the boat on the jetty and are admiring the round, organic lines, as can be heard through the open saloon hatch. These boats are simply timeless, defy trends and fashions and are pleasing to the eye because their designers didn't care about racing formulas back then, didn't give them measuring bumps or artificial overhangs, didn't design superstructures as angular as boxy white bread. The Danes are known for this in many areas, furniture, lamps, kitchen appliances - and even yachts. It's like the VW Beetle - somehow everyone likes its curves. Even today. And indeed, the Grinde was a similar blockbuster. Around 600 units were sold, an impressive number for boat building. If you keep an eye out, you can find one in every second Danish harbour.

The father of this eye-catcher is the Dane Peter Bruun, who created a whole series of pointed galleys of various sizes in the 1970s, all named after whale species, which also had an impact on the design: Spækhugger, Marsvin, Kaskelot and Grinde - after the Danish name for the pilot whale. Visually based on traditional shapes, yes, but the boats were not meant to be slow; designer Bruun is still an ambitious regatta sailor today. His designs are known for sailing fast and are considered robust and seaworthy. There have been and still are various Atlantic crossings with them, including circumnavigations, currently even single-handed by YouTube blogger Holly Martin (www.windhippie.com).

Grinde community is active

However, it is astonishing that the boats still have a lively community, as we would say today: in Denmark, there is the Grinde Klub, which has its own website with valuable information and organises annual meetings and trips. And there is even a loose association on the German side of the Baltic Sea: over the years, a community of around 20 fans of the cuddly boats has come together via a signalling group (alternative to WhatsApp). Meet-ups are organised here, repair tips are discussed and pictures and videos are shared. The motto of the scene is something like this: You don't choose the grind, it chooses you.

Their spiritus rector is the Hamburg yacht surveyor Uwe Gräfer, who has sailed, cared for and looked after a Grinde himself for many years and is the co-author of a book on the cultural history of the modern topsail. We meet him in Kiel for the test.

"The Grinde was a very carefully built, solid ship at the time. In the end, that was probably a bit of a downfall for the shipyard," he says. "The boats were very expensive back then, at Rassy level. Also in terms of quality. Bruun first built them in co-operation with the Flipper Scow shipyard, later he built them in his own shipyard. At times, things went so well that the hulls and decks were also built by LM," says Gräfer.

Used boat profile of the Grinde

- Type: Grind

- Designer: Peter Bruun

- Built: 1974-1989

- Quantity: approx. 600

- New price ready to sail: approx. 75,000-80,000 DM

- Used price current: 16,000-30,000 euros

Weak points of the grind

Hull in full laminate, deck with balsa core: "The latter is one of the few Achilles' heels of the boats. You have to pay careful attention to leaks around fittings, handrails and mast, otherwise water can penetrate, causing the core to soften." Discolouration on the inner wooden handrails below deck or on the cork insulation in the interior are telltale signs.

Another known weak point is the mainsheet traveller. "It is simply attached to a hollow platform without any further reinforcements on the inside using threaded screws. Cracks can develop over the years at the base on the outside, where the platform joins the deck." So buyers should take a close look.

The community has developed its own fix for this problem: If the balsa core around the areas is still dry, which unfortunately can only be determined by drilling one or two test holes from the inside, the cavity is filled with epoxy resin step by step. Proceed with caution, there must not be too much resin at once and it must react slowly, otherwise it will become too hot. Then repair the cracks in the gelcoat. In most cases, this solved the problem. The boat has no other critical areas. Osmosis is rare, the fittings, winches and mast are of very good quality, and the floor assembly is very solid.

Genoa as an accelerator pedal

But now the Grinde should show what it can do under sail. The sails are set on the mast as standard, deflected halyards, spreaders and furling genoa are almost always retrofitted by the owner. The way forward is pleasing, the boat has very nice wide running decks, in contrast to some designs of this size and time.

As a representative of the IOR era, the Grinde has large headsails, the Genoa 1 originally measured up to 150 per cent, but hardly anyone sails like this anymore. The extremely long genoa track, which reaches just in front of the cockpit, allows a wide range of hoist point settings. Just like the practical perforated rail that runs along the entire length of the hull on both sides, which makes it possible to move spinnaker points, extra jib cleats or other items as required.

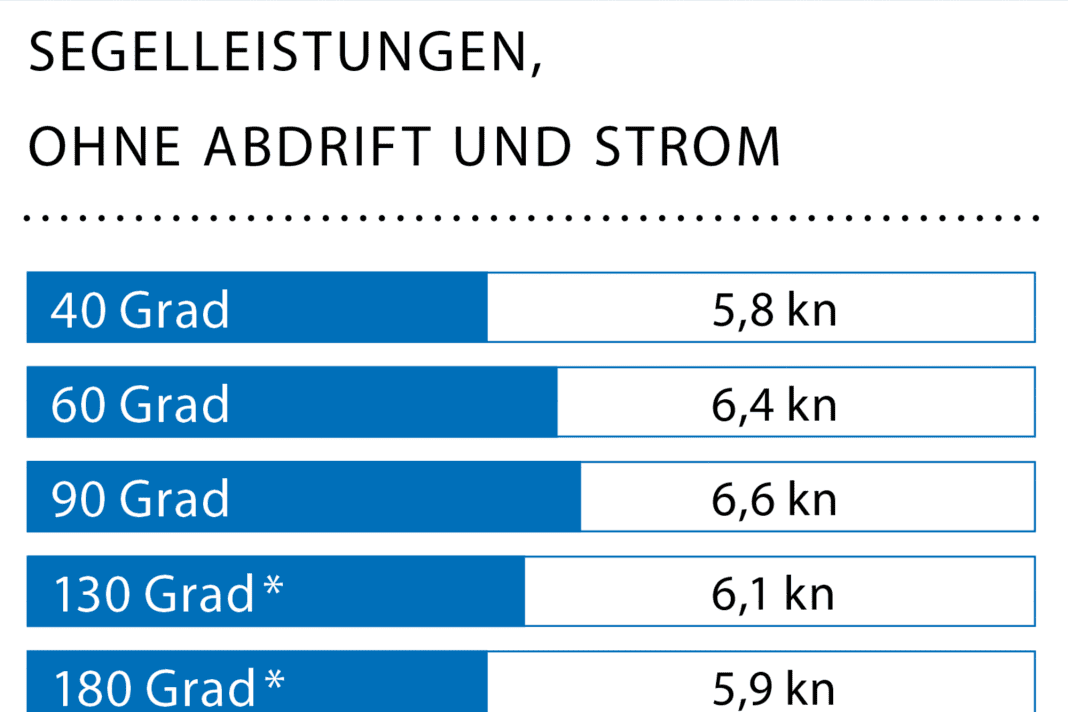

The genoa is therefore the boat's accelerator pedal: once it is set, the Grinde lies on its side and sets off. The very wide ship does not sail with an unnecessary amount of leeway, like some of the more classic designs of the seventies. At 4 Beaufort, she sails off at full sail, and on the log, the 6.6 knot hull speed is reached surprisingly quickly at 60 degrees upwind.

The attached rudder is pleasingly easy to steer; the pronounced and sometimes annoying rudder pressure of some boats with an attached rudder and skeg does not exist here, regardless of the course. The Grinde is also willing to tack upwind, turning angles of 85 to 90 degrees, which are usual for cruising yachts, are no problem, even then it still makes rapid progress. The boat is easy to steer, even in the few pushes above the 15-knot limit, it is controlled on the rudder.

Rigging and line management

"The Grinde is known for its good strong wind characteristics. The shape goes very smoothly through the waves and can withstand a lot of pressure," says Gräfer. "In winds of over 10 knots, you can often leave even much larger yachts behind." The necessary trimming equipment is available. The backstay tensioner, which is operated by a rotating mechanism, can generate a lot of tension, so there is no excuse for a lot of forestay slack. On the test boat, the traveller was driven via two winches on the cabin roof.

The one-saling top rig is almost 13 metres long and is inserted through the deck. Although the mast was foamed on the inside to prevent leaks, the foam plug ages over the years and many boats have some water in the bilge when it rains continuously. This is a well-known problem with such rigs, but it is usually less than a cupful.

A special feature of the Grinde is the mainsheet guide: it is guided via a deflection from the traveller in front of the companionway to a clamp on the boom cleat, from where it then hangs loosely down into the cockpit - an arrangement familiar to dinghy sailors from modern skiffs. This keeps the cockpit free of tripping hazards. Barlow winches on the coachroof were used as standard to control the genoa sheet. However, they were often replaced by genoa winches on the side deck so that a sprayhood could be fitted. This was also the case on the test boat. The baby stay in front of the mast takes some getting used to, as it tends to hold up the very large genoa when tacking. It takes a while for the crew to find the fastest technique for themselves.

Pleasingly agile at sea, tough when manoeuvring in port

As if on rails, the Grinde ploughs through the Kiel Fjord near Schilksee with its wide, massive stem, which is almost modern again today. No water gets into the deep, but typically small cockpit, and the sprayhood, which is pulled far aft, also provides excellent protection. Various size variations have been installed. What some of them have in common, as in our case, is that they cannot be lowered when sailing, so the mainsheet chafes.

The Pilot Whale thus sails in circles, gives a pleasingly agile impression and starts up again immediately after small wind holes in the gusts - a really good sailing cruising yacht. The boat is equipped with a 70 square metre spinnaker as standard, the boom of which is stowed in very attractive, robust brackets on deck.

At some point, however, we have to return to the harbour. There, the Grinde shows the typical peculiarity of skeg boats: it manoeuvres backwards very slowly because the skeg at the stern has a course-stabilising effect. This takes time, especially when manoeuvring against the powerful wheel effect of the fixed shaft with the controllable pitch propeller fitted. At the stern, the massive stainless steel cleats are noticeable; at the bow there is only one cleat.

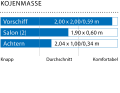

Surprisingly voluminous inside

In the harbour, the Dane plays her trump cards below deck. The hull is very wide for a length of 8.20 metres - 3.12 metres - which provides a huge amount of space. "The Grinde was explicitly advertised as a family boat. That's why there were seven berths, including two raised pilot berths, which are ideal at sea," comments Uwe Gräfer. In fact, going below deck is a surprise for many: you imagine yourself to be on a much larger boat. The feeling of space is more reminiscent of ten metres than eight, and that's without the bulky, boxy superstructures.

The layout is very cosy and classic: a small but functional galley on the port side with a two-burner paraffin or spirit cooker, sink and a refrigerator compartment, which many owners have retrofitted with a compressor unit. The space for this is limited, so some build it into the abysmally deep port side locker, in which even a person can disappear.

Special features below deck of the Grinde

To starboard is a very spacious, over two metres long and wide dog bunk, which is also a seat at the folding chart table with a generous compartment for nautical charts. The only downside is that the head end of the bunk gets clammy if you sit there with wet oilskins. But in the age of tablet navigation or plotters in the cockpit, this is a solvable problem.

Below deck, a special feature of the boat immediately catches the eye: the sides of the boat are lined with natural-look cork panels for insulation. "That's not to everyone's taste, but the panels prevent condensation," reports Uwe Gräfer. However, it is advisable to check the bonding, otherwise mould can form behind it. "The cork is otherwise grateful. If there are stains or traces of wear and tear, it can be lightly sanded. Then everything will look good again for years." There is no ceiling panelling on the ship. The four breakfast-board-sized saloon windows on both sides and two hatches above bring light below deck. Anyone replacing them should switch to glued ones, which are now state of the art, and fill the holes to minimise the risk of leaks.

Missing anchor locker

The huge third hatch in the foredeck is surprising: it is solid GRP, reaches almost to the bow and was originally intended to allow the staysails to be changed. Today, it is mostly only used for ventilation and has the disadvantage that there is no anchor locker accessible from deck. Although there is still space in front of the berth, you have to dig out the anchor from below.

In reality, many owners do things differently, as Uwe Gräfer knows: "With pointed gates, it doesn't matter whether the anchor is deployed over the bow or stern. Many have it stowed in the cockpit locker or under the centre cockpit bulwark. For anchoring, they simply throw it out over the stern with a chain leader and rope and then pull the boat round by the rope." A feasible way.

However, if you want an electric anchor windlass with a chain locker, you will have to make more complex modifications at the front. In order to have space for a roller in front, some also retrofit larger bowsprit solutions. However, this brings tears to the eyes of purist Gräfer.

The bunk at the front is huge, even two-metre-long guys can fit in. Behind it is a washbasin and cupboards on one side and an open toilet on the other - typical of the eight-metre class of the time. The large saloon behind has the original four berths, two below and two above. If you fold up the backrests of the saloon benches, various drawers and cupboards are revealed, offering plenty of storage space. And two narrow but safe sea berths are created above.

Pricing

An important point when buying a used machine is the engine. The Grinde was equipped with a 10 hp single cylinder from Bukh with single-circuit cooling as standard. "This is actually too weak for the boat. When we change, we almost always go for twin cylinders with around 20 hp," says Gräfer. This is also reflected in the price. "Well-maintained boats with a replacement engine cost up to 30,000 euros; less well-maintained models started at around 15,000 euros before the coronavirus. Now it's more like 17,000 to 18,000 euros.

There is a market in Germany; many boats can also be found in Denmark, Sweden or Holland. But if you have a serious crush on a GRP classic, there is probably no distance too far to your new piece of jewellery.

What buyers should look out for

Where it is worth looking so that winter work does not seamlessly lead to expensive repairs

The measured values for the grind test

The crust in detail

Technical data of the grinder

- Design engineer: Peter Bruun

- Torso length: 8,20 m

- Width: 3,12 m

- Depth: 1,70 m

- Weight: 3,4 t

- Ballast/proportion: 1,6 t/47 %

- Mainsail: 19,0 m2

- Furling genoa (140 %): 26,0 m2

- Spi: 70 m2

- Machine (Bukh): 7.3 kW/10 hp

Hull and deck construction

- Hull: solid laminate in hand lay-up process

- Deck: Sandwich with 10 millimetre balsa wood core

Price and shipyard

- Base price ex shipyard: approx. 75-80,000 DM

- Price today: 16-30.000 €

- Built: 1974-89

Status 02/2024

Shipyard

Flipper Scow no longer exists; parts, information and repairs are still available from the Peter Bruun shipyard, www.peterbruun.dk

YACHT rating of the Grinde

Visually very harmonious design with good sailing characteristics and very solid build quality with few weaknesses. Rather small cockpit, but plenty of space below deck. Archetypal modern GRP classic

Design and concept

- + Coherent design and concept

- + Solid construction quality

Sailing performance and trim

- + Good sailing performance

- + High-quality fittings

- - Weak mainsheet traveller

Living and finishing quality

- + Enormous amount of space for the length

- + Simple but functional kitchen

- - No separate toilet room

Equipment and technology

- + Good winches

- - Original motor too weak

- - Traps and stretcher on the mast

The crust in the video

The article first appeared in YACHT 15/2021 and has been updated for the online version.

Also interesting:

- Hornet 32: High-quality cruising boat from the Elbe in a used boat test

- Biga 24: Beautiful, fast and complete, even as a used boat

- Hallberg-Rassy 342: Popular used boat offers the usual quality

- Mitget 26: Solid from the Netherlands in a used boat test

- The little brother of the Grinde: The Speakhugger in the test

Andreas Fritsch

Editor Travel