A lot has changed at the likeable, pragmatic brand from the rugged north of Brittany. Even if you don't realise it at first glance, Boreal is resolutely breaking new ground in both large and small ways. Of course, the 56, the latest model from Tréguier, is still an explorer yacht, suitable like few other production boats for truly worldwide cruising, even in the high latitudes. The unpainted aluminium hull with the welded-on cleats, the battering ram-like anchor gallows and the equipment carrier at the stern make it unmistakably clear from afar that the shipyard has designed a tool for long, tough voyages - a cruising ship with ice class, so to speak.

That is also interesting:

Nevertheless, Jean-François Delvoye, designer and co-partner of the shipyard, has resolutely opted for modernity when it comes to the lines of the 17-metre cruiser. The most visible feature of this endeavour is the now circumferential window strip of the superstructure, which beautifully integrates the previously individually framed saloon windows and lends the Boreal 56 a certain elegance.

Less obviously, but no less consistently, Delvoye has adapted the hull shape to current trends. The lean Frenchman with the sun-tanned skin and sparkling eyes, who spends months at sea himself every year, has given his boat a kind of moderate scow-bow design, which has been increasingly popular with ocean racers for years.

Although he did not completely round the foredeck and retained a stem - no comparison to the almost clog-like bows of today's Mini 6.50 and Class 40 - the edge of the deck shows how quickly the 56 gains width and how much volume it already has in the first third of the boat. Her forefoot is even bevelled like some Imoca 60 racers to generate dynamic lift and minimise the bow diving in the wave.

As if on rails

Otherwise, a 20-tonne explorer bears no resemblance to a foiling carbon racer. The bulky bow section also serves very different purposes. On a cruising boat, for example, it creates a lot of additional storage and living space below deck. However, Jean-François Delvoye also opted for this design principle because it offers sailing advantages: "Our new boat has greater symmetry in the waterline. As a result, it doesn't trim as much in the water, is more stable lengthways and also sails drier thanks to the additional buoyancy."

On the 400 nautical mile crossing from Tréguier to IJmuiden in Holland, he was able to put his latest creation through its paces in winds of 35 to 40 knots, gusting to over 50 knots and chaotic seas. The boat, he says, "ran like it was on rails". The crew only needed two days to complete the route. "Apart from the jibes, we were on autopilot the whole time. Not once did the yacht go off course."

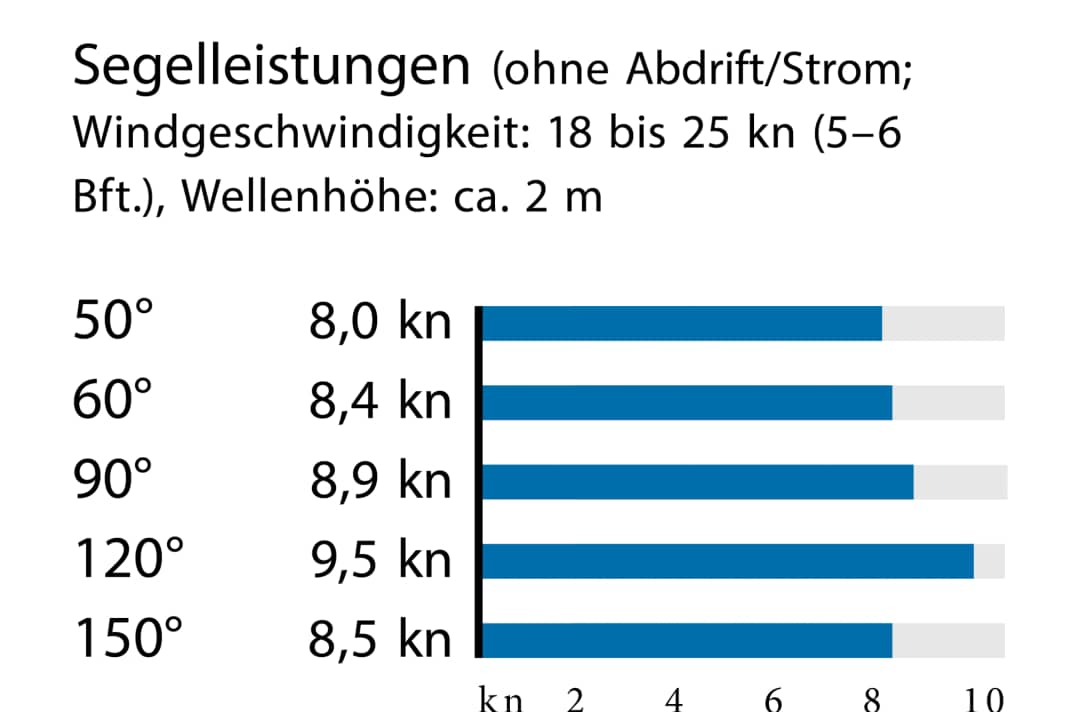

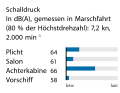

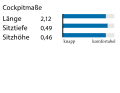

Measured values of the Boreal 56

So it's fitting that a secondary front on the North Sea sweeps the rain horizontally over the jetties of the Seaport Marina for three days and condenses the sea into a Caspar David Friedrich painting: a grey-green-steel-blue force of nature, so raw and unbridled that it's impossible to think about setting sail at first, because at force 10 even manoeuvring in the harbour would be a game of vabanque and the five-metre waves break outside the long piers.

A speciality: Auxiliary rudder

When the wind drops to 5 to 6 Beaufort for a few hours on the third day, the Boreal 56 has to prove that she can actually do what her architect promises. With a single reefed main and genoa, she lays on her chine, heels only moderately to around 20 degrees and then, unimpressed by the rough sea, runs steadfastly upwind as if it were a warm-up exercise. Hardly any corrections are needed on the wheel, which is also thanks to the auxiliary rudder that can be lowered aft to leeward.

The profiles are one of the many specialities of every Boreal, are made of GRP and run on both sides of the midship line in fully welded aluminium boxes. The shipyard uses them to compensate for the limited efficiency of the central main rudder, which is quite short to allow the yacht to fall dry on its own keel. The system can be operated from the cockpit and has proved very successful. On the one hand, it ensures course stability and relieves the helmsman or the autopilot. Secondly, the auxiliary rudders can be raised in seconds - for example when approaching a flat or in the event of an orca attack.

The central rudder, on the other hand, is made of aluminium. Its leading edge consists of a thick and virtually indestructible aluminium tube, to which bent plates are welded at the sides, which are also firmly connected to the rudder shaft. The ballast centreboard is constructed in a similar way, except that a round bar made of solid material is used instead of a tube at the front end.

Safety is a top priority with the Boreal 56

The shipyard's focus on safety is demonstrated not only by the narrow frame spacing of 70 centimetres and the wide T-profiles for longitudinal and transverse hull reinforcement. The star-shaped support of the quadrant, a good half metre high, which distributes the loads to the surrounding structure in the event of a collision, also far exceeds all building regulations. In addition, both the aft and forepeaks have watertight welded bulkheads made of four millimetre thick aluminium sheet. The keel sole is ten millimetres thick, the keel flange ten millimetres and the hull sides between eight and five. It is a design based on the Pantaenius slogan "Whatever you like can come".

If you steer the Boreal 56 more or less square into a three metre high caveman for test purposes, the effect of this construction method can be impressively experienced. Because apart from a soft jolt that goes through the ship - nothing happens! No twisting, no shaking, no banging in the waves. Not even the Seldén rig, which is well supported by two pairs of spreaders swept aft and a two-part backstay, starts to pump noticeably.

The speed through the water and the height upwind are very good for the conditions. However, it is above all the nonchalance with which the boat defies the elements that impresses. You could watch the spectacle from the doghouse, which offers an almost unobstructed all-round view and even a view of the mainsail through two hatches. You could sit in the cockpit under the overhanging roof of the cockpit, protected from rain or spray. But both would mean missing out on the fun of active sailing.

Simply outstanding

This is because the layout of the helm stations and the working cockpit is simply outstanding, with one exception. Helmsmen will find the best working conditions both standing up and sitting sideways. The view across the deck and into the sails is not restricted even by the doghouse - helpful when approaching atolls or ice fields, but also a benefit in other respects. The arrangement of the winches is such that both the genoa and mainsheet can be deflected to windward, which facilitates single-handed operation. Only the working height of the aft winches seems a little too low, which is why their electrification is recommended.

Otherwise, the ergonomics are a model for seaworthy yachts: There are handholds everywhere, whether in the cockpit, on the cabin superstructure or on the mast, where even "granny bars" make it easier to work on headsail halyards and reefing lines. Hoisting the mainsail or clearing excess cloth after reefing is made much easier because the roof of the deck saloon ensures a safe working height. All features that show that the shipyard regards heavy weather operation as the norm, so to speak.

Only a few points on the test boat were not to our liking. For example, the anti-slip paint on the cockpit coamings and on the cabin roof proved to be insufficiently grippy in wet conditions. The gas pressure dampers of the pleasantly large, but therefore heavy hatches to the aft forecastle were too hard to hold. And the huge stowage compartments, which are accessible from the deck, need to be subdivided in order to be usefully utilised. With a volume of three cubic metres, the forepeak is so large that an additional collision bulkhead seems sensible; should there be a massive ingress of water here, the yacht will not sink, but it will trim heavily top-heavy. This can only be remedied by rigging all the fenders forwards and the room windsails aft, but this means unnecessary towing.

And below deck?

Oh, what silence, what surreal isolation from all the elements! Nothing crackles or squeaks, no matter how it's sweeping outside. The cupboards and drawers remain closed. The noises fade away. When the armoured cabinet-like door of the doghouse falls into its lock, it seems as if there are no 6 Beaufort outside, but at most 3 to 4.

Here, too, there are handrails everywhere where you intuitively look for them. Tables, shelves and work surfaces still have proper edging, the showers have deep sumps so that they can still be used at sea. And then there is the Refleks stove, which creates cosiness in the harbour or at anchor without consuming electricity. It can also be spliced into the glycol-led central heating system by means of a heat exchanger, which Boreal can also install on request and which can be operated at sea. Ice class, as we have already mentioned.

The well-insulated engine room still offers enough space for screwing even when the generator and watermaker are installed. The central cabin has perfectly chosen lines of sight - both when seated from the raised seating area and standing in the galley.

All this practicality was also available in earlier models of the brand. However, the Boreal 56 offers that decisive extra everywhere: twice the tank capacity of the 47.2, for example, comfortable berth dimensions throughout, good headroom almost throughout the entire boat. And the interior has undoubtedly gained in finesse. The new model almost conveys the elegance and distinction of the luxury class, but far surpasses it in terms of seaworthiness and safety. A promising synthesis!

YACHT rating of the Boreal 56

The Boreal 56, the latest model from the brand renowned among long-distance sailors, has gained in elegance and sophistication without making the slightest compromise to its imperturbability. In rough seas it remains a fortress, at anchor it is gradually almost competing with the luxury class. Chapeau!

Design and concept

Key long-distance explorer

Safety and seaworthiness

Top weather protection thanks to pot-tight locking doghouse

Sailing performance and trim

Respectable potential for tourers

Variable cockpit layout

Easily accessible large tree

/(-) High course stability, somewhat high rudder pressure

Living and finishing quality

Solid, precisely fitting woodwork

Fantastic panoramic view

Handles and sling bars everywhere

Consistently good comfort dimensions

Equipment and technology

High-quality components

Outstanding storage space

Lack of forced ventilation in forecastle/saloon

Features and prices of the Boreal 56

- Base price ex shipyard: 1.486.900 €

- Standard equipment included: Engine, sheets, railing, navigation lights, battery, compass, sails, cushions, galley/cooker, bilge pump, toilet, fire extinguisher, electric coolbox, holding tank with suction, antifouling

- For an extra charge: Lazybag € 2,820, 2 anchors with 100 m chain € 6,240, fenders/mooring lines € 2,010, clear sailing handover € 11,820

- Price ready to sail: 1.509.780 €

- Guarantee/on structure: 2/5 years

- Surcharge for comfort equipment: Line adjustment points incl.; Traveller with line guide incl.; Electric windlass incl.; Tube kicker incl.; Backstay tensioner incl.; Jumping cleats incl.; Sprayhood/doghouse incl.; Teak in cockpit incl.; Navi package (radio, plumb bob, log, radar, GPS) 23.490 €; autopilot/wind sensor 19,020 €; charger incl.; shore power with RCD incl.; 230-volt socket (one) 280 €; 12-volt socket in the sat nav 280 €; heating 14,890 €; pressurised water system incl.; hot water boiler incl.; shower WC room incl.; cockpit shower incl.;

- Comfort price: 1.567.730 €

- Included in the price: Ballast centreboard, lowerable centreboards aft for course stability, cockpit table, electric central winch, raised saloon, oak interior

As of 2025, as the prices shown are defined, you will find here!

The Boreal 56 in detail

Technical data of the Boreal 56

- Design engineer: Jean-François Delvoye

- CE design category: A

- Torso length: 16,00 m

- Total length: 17,12 m

- Waterline length: 14,47 m

- Width: 4,94 m

- Depth: 1,20-3,18 m

- Mast height above WL: 23,20 m

- Theor. torso speed: 9.2 kn

- Weight: 20,5 t

- Ballast/proportion: 6,6 t/32,2 %

- Mainsail: 74,0 m²

- Furling genoa (120 %): 69,0 m²

- machine (Yanmar): 59 kW/80 hp

- Fuel tank: 1.150 l

- Fresh water tanks (2): 1.500 l

- Holding tank: 85/110 l

- Batteries: 4 x 165 AH + 1 x 115 AH

Hull and deck construction

Fully welded aluminium construction, keel made of 12, hull bottom made of 10 mm solid material.

Storage compartments

Both on and below deck, the Boreal offers an unrivalled amount of space in this class. The fore and aft peak alone swallow up more than twelve (!) cubic metres of stowage.

Redundancy

Watertight welded bulkheads in the bow and in front of the quadrant make the boat practically unsinkable. Two heaters are available on request: a hot-air heater and a Refleks stove, the output of which can be combined, making the Boreal suitable for the Arctic. Two completely separate autopilots are also available on request.

Shipyard/direct sales

Boreal SARL, ZA Convenant Vraz, F-22220 Minihy-Tréguier, T. +33 296 92 44 37, voiliers-boreal.com