"Undine": The first 55-metre pointed-boom sailing vessel ever built is a contemporary witness after an intensive refit

Andreas Fritsch

· 02.08.2025

There are these stories in the classic boat scene that make you think a higher power has a hand in it. This was the case in 2016, when Marstal's best-known wooden boat builder, Ebbe Andersen, who had been restoring and building traditional wooden yachts and workboats for decades, returned with his wife Gerda from a trip to Sweden on their Colin Archer "Thor". They stopped off in Helsingør on the Øresund and bumped into Bent Okholm Hansen on the jetty. He is the owner of one of the rare and beautiful 55er pointed gates, of which only three were ever built.

This might also interest you:

The owner and the boat builder naturally get talking about the beautiful 55 at the jetty, and Okholm Hansen casually tells us that the second 55 still in existence in Denmark is on land not far from Gilleleje and has been slowly decaying under a tarpaulin for over a decade.

"I had heard about the ship as a young boatbuilder, and at the time there was talk of a very large pointed gate in Copenhagen. But I never got to see it. It was something of a legend, a masterpiece by the great designer Aage Utzon," says Ebbe, as everyone calls him.

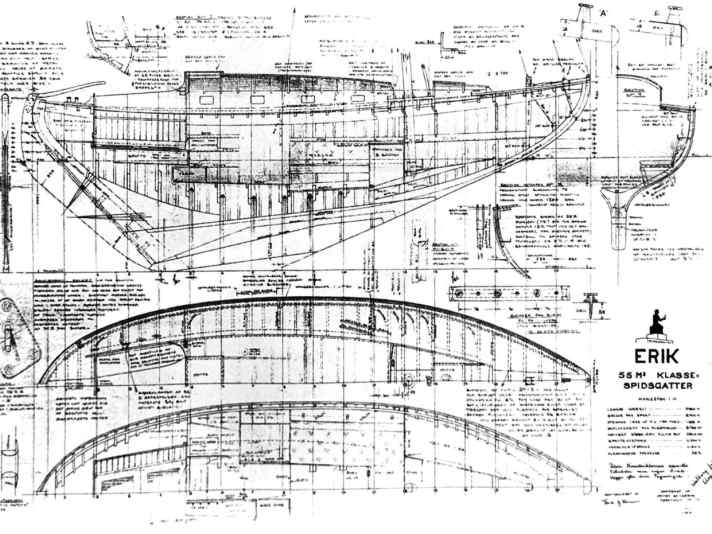

"And as luck would have it, in the 1980s I had even written to the family of the now deceased designer for a customer of my shipyard and asked for a crack of his 55. The customer was considering a replica. I received a drawing, but nothing came of the new-build project." But the lines of the pointed gaff were already exceptionally appealing to him at the time.

"I knew immediately: that's it!"

The 55er Spitzgatter is, so to speak, the premier class in the development of the class Spitzgatter scene, which was further developed as touring and regatta boats built from the classic working boats of Danish fishermen. They experienced their heyday from around the 1920s to the 1950s. With a sail area of 55 square metres and a hull length of almost ten metres, the 55s were the largest boats of their time. This is probably one of the reasons why only three boats were built. Most pointed-gate class boats were significantly smaller.

And so it came as it had to. "Gerda and I started to think about it. In our mid-60s, we had come to the conclusion that at some point we would no longer be able to handle our 13-metre Colin Archer because of the rather heavy gaff rig. So we were already looking for something more manageable so that we could continue sailing for as long as possible." This gave rise to the idea of contacting the owner.

He turned out to be the boat builder who had bought the ship in poor condition in 2000 and had started to restore it, but simply hadn't found the time to make any progress. Ebbe and Gerda travel to Gilleleje, but don't meet the owner there. However, Ebbe discovers the boat in the yard under a tarpaulin. "I knew straight away: that's it!" The owner had renewed the deck, refurbished the stern and built a new rudder. "Good work!", Ebbe recognised. And the owner didn't actually want to sell, but at some point he realised that there could hardly be a better opportunity to give "Undine" a second lease of life if the boat went to a well-known and renowned boat builder like Ebbe.

Three years, more than 2,000 hours of work

"I realised that it would be a lot of work, but I'm a professional, I knew exactly what we were getting into and what it would cost!" said Ebbe. The only thing that mattered to him was that Gerda had to be involved. It wouldn't work without his wife's blessing. And he had already restored her Colin Archer "Thor" with her from 2010 to 2013. Who knows whether she would be up for such an extensive refit again just three years later. After all, they were both in their late 60s at the time, but he worried for nothing: she had fallen in love with the battered beauty just as much as he had.

And so "Undine", the first 55-metre spitsail ever built, is lorried to Marstal on the island of Ærø. The inventory showed the route for the next few years: "The wooden part of the keel was cracked and had to be rebuilt. That was the biggest construction site. But the oak frames were all solid. Some of the pine planks had to be stripped, and the hull had to be completely stripped of old paint and re-caulked," says Ebbe. But the substance was otherwise good, the Oregon pine rig only needed eight new coats of paint, as did the mahogany interior. The two show pictures of the refit: Gerda with a hot air gun stripping paint, Ebbe calendering, the construction of the new keel.

"We spent three years and more than 2,000 hours working on the boat," say Ebbe and Gerda over coffee and cinnamon buns, talking about the intricately detailed plans. After the many anecdotes about the restoration, it's finally time for the boat. So down to the jetty of the Marstal Sailing Club, less than 50 metres from Ebbe's old shipyard in the red and white wooden shed.

Ebbe sees the ship as a contemporary witness, it should be kept as original as possible and later passed on to the next generation.

The imposing mast of the 55 stands out: 18 metres on a wooden boat almost 10 metres long, filigree jumpstays in the top, backstays. And then those hull lines. The deck is beautifully shaped, narrow and elegant, the flat cabin superstructure nestles beautifully into the lines. The slender hull merges into Utzon's trademark at the bow, a very voluminous, strongly rounded stem. "It's really very wide," smiles Ebbe when I look at it, "a massive 25 centimetre wide piece of wood! Quite typical for Utzon!" The massive bow, which is en vogue again today, provides more volume in the foredeck and should allow the boat to move smoothly through the waves. In fact, the pointed gates from his pen are known for their excellent seaworthiness in the often short and rough Baltic Sea waves. Utzon's pupil Peter Bruun continued the idea later in the 1970s in the popular GRP pointed gates Spækhugger and Grinde.

"Undine" is kept as original as possible

And then, of course, the beautiful, gently rounded stern. It looks elegant and graceful, as is usual with pointed gates, a boat that is as beautiful at the back as it is at the front. The hull is white, the plywood deck and pine cabin roof in the lime green of the Marstal schooners and workboats, to which Ebbe is deeply connected through many new builds and above all the renovation of the schooner "Bonavista". What is striking, however, is that "Undine" is in no way modernised for the ship of a married couple in the 70s: Furling foresail, sea fence, bow or stern pulpit, deflected halyards - not a thing. That would never occur to Ebbe: "It was important to us to keep the boat as original as possible," he says when asked about this. It should remain a kind of sailing contemporary witness.

Paradoxically, it was precisely for this reason that the Andersens decided to make a radical change to the pointed batten during the restoration: "The boat was built in 1936 at the Lilleø shipyard for a Copenhagen watchmaker. Although the drawing for the cabin superstructure by Aage Utzon included windows, the owner left them out and only a skylight in the deck provided light. We don't know why," says Ebbe.

"That's the fascinating thing about wooden boats: 'Undine' has been sailing for 80 years. And once we're gone, she'll be able to do it again."

Perhaps his privacy was important to him. In any case, the first owner was an original character. He was known for sailing through the Danish archipelago on his holidays and asking the locals in every harbour if anyone had a watch to repair. If they did, he asked them to take it with them and bring it back repaired on their next visit by boat. In any case, Ebbe put the saw to work and cut out the windows afterwards.

Old-school sailors

But now it's time to go sailing off the coast of Marstal. Wind force three is blowing outside. The owner couple decide in favour of the working jib, as the boat has plenty of sail area. The boom extends well up to the centre of the cockpit - and used to be significantly longer. "The original boom practically went all the way to the stern, but the last owner shortened it a little. The rudder pressure was too great for him. As a result, the sail is four square metres smaller."

As was customary in the past, the main halyard is operated directly on the mast, while the small mast cockpit around the base of the mast allows a good stance. The sails fill up, "Undine" leans to one side and sets off unperturbed despite the small working jib. The ship lies comfortably on the attached rudder, helped by the long tiller. The cockpit is deep and the crew is very well protected. What is striking is that there are no forecastle boxes under the cockpit thwarts. Ebbe explains why: "Topgates are sensitive to trim due to the low buoyancy in the stern area. Even when the cockpit is full, the stern dips deeply. Utzon didn't even draw any in the first place so that the owners don't exacerbate this by overfilling the cockpit."

The deck of "Undine" has clear lines, is very uncluttered and comfort such as a sprayhood is out of the question for the Andersens. They are old-school sailors, even if they "only" sail for a maximum of six to ten hours at a time, as Ebbe notes. Meanwhile, his enormously strong hands, which bear impressive witness to a life as a boat builder, grip the tiller almost tenderly. You can feel that "Undine" and he are a perfect match. You could do endless laps like this in the bright sunshine off Marstal, the 55 elegantly lapping its way.

Temporary custodian of a cultural asset

What is surprising is the saloon: it ends directly in front of the mast, with a bulkhead in front of the pipe separating it from the foredeck. If you want to get to the berths there, you have to go below deck via a second companionway in front of the rigging. Unconventional, but also consistent, as Ebbe finds. Structurally, of course, this has many advantages, and it is not easy to pass the mast on the left and right anyway. Stowed wet sails or equipment were also spatially separated from the saloon.

A simple galley with a two-burner spirit cooker, a spartan wet room on the starboard side with a small wash basin and toilet, some cupboard space and room for the nautical chart - that's it. The only recognisable concession to modernity is an iPad holder with power supply; there is no plotter. A simple, aesthetically unpretentious ship, no matter where you look. A sailing piece of contemporary history.

The owner couple happily sails their "Undine" in Danish waters on their doorstep. Should this no longer be possible at some point, they hope to find a successor who appreciates what they have created through the restoration: "'Undine' had already sailed for 80 years before we took her over and can continue to sail in exactly the same way for another 80, long after the two of us are no longer around. That's the fascinating thing about old wooden boats!" says Ebbe. The owner as the temporary custodian of a cultural asset. It's great that there are still people like that around today.

Spitzgatter - In a class of its own

The 55s were the largest of a total of six pointed-gear classes with a sail area of 20 to 55 square metres. It had its heyday from the mid-twenties to the fifties. At that time, the Dansk Sejlunion gradually introduced them as national regatta classes and around 300 measured regatta boats were built at all kinds of shipyards in Denmark. In addition, there were probably over a thousand similar ones for pure cruising sailing, whose builders did not follow the class-compliant measurement formula. They were considered to be a further development of the Danish fishermen's workboats, more precisely the kragejolle, which travelled the Öresund as a bread-and-butter vessel. They were largely open, around eight metres long and clinker-built boats with the typical pointed batten stern. A shallow draught for coastal fishing, bulbous over but narrow in the waterline - that was their typical silhouette.

The driving designers of the class at the time were initially the Danes Aage Utzon (1885-1965) and Georg Berg, who were joined somewhat later by M. S. J. Hansen. Berg's "Kuling" design from 1914 is considered the archetype of the class, so to speak. Hansen was also responsible for the only other 55-point rig still sailing, the "Neptun", whose owner Ebbe met and who told him about the Utzon ship in Gilleleje. A third boat, again a Hansen design and sister ship to the "Neptun", is said to have been built in Denmark in 1937 and exported to the USA shortly afterwards. There are rumours that it is still somewhere in disrepair, but nobody in the Danish classic boat scene knows anything more about it.

Speciality of Danish boatbuilding

Utzon's designs were considered to be elegant, fast boats of the class, and he was an experimental designer when it came to lines. Born in Aalborg in 1885, the Dane was actually a shipbuilder at the local shipyard. His first sail design, which earned him widespread acclaim, was the gaff cutter "Shamrock" in 1918. It was also around this time that he and his design competitor Georg Berg endeavoured to establish the pointed gaff as a national class at the Danish Sailing Union. Sailing as a regatta sport had only gradually emerged in Denmark at the end of the 19th century. The efforts of the designers bore fruit in 1925, when the Sailing Union announced the first pointed creel class. Over the following years, the six square metre classes 20, 26, 30, 38, 45 and 55 were created.

Utzon's competitor Georg Berg was a trained shipbuilder who developed more from sailing practice. His ships are characterised by slender, rather narrow sterns with small cockpits and plenty of deck space. Hansen was the youngest of the three and only joined later, but his designs are regarded as harmonious-looking, legendarily seaworthy boats with a tendency towards more volume. This can still be seen today. When "Undine" happened to be moored in the harbour next to the other 55 "Neptun", she appeared to be the more graceful, elegant boat. What all the designs had in common was that the pointed gates were intended to be simple, affordable boats at the time. The hulls were made from inexpensive, local woods, including "Undine", whose planks were made from pine. This is another reason why the hulls are often white in colour. The structure was usually made of oak, while the sides of the "Undine" were made of acacia.

Technical data of the 55 "Undine"

- Year of construction: 1936

- Length: 9,98 m

- Width: 2,74 m

- Depth: 1,90 m

- Displacement: 5,9 t

- Ballast: 2,8 t

- sail area: 51,0 m²

- Original sail area: 55,0 m²

The portrait of the "Undine" is published in the current issue of YACHT classic, which has been on sale since 21 May (available here). YACHT subscribers get the magazine delivered to their door for free. You can also read the portrait of shipyard founder Henry Rasmussen, the history of the "Nordwest" and look back on Classic Week 2024 in photos by Nico Krauss.