- Nothing on board the Gozzo is made of plastic

- Sailing all-rounder

- Formerly a tuna boat, today more of a bathing boat

- Where there used to be fish traps, lead now helps on the Gozzo

- Bella Figura under sail

- Legendary pizza evening arouses interest in the Gozzo

- Like an original from the old days

- Capital of tuna fishing

- Technical data of the "Luigi Padre"

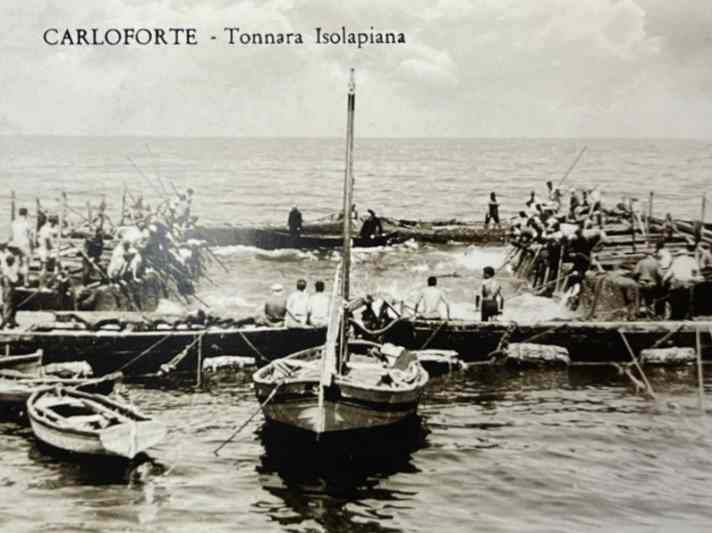

If you want to understand the maritime history of the Isola di San Pietro, all you have to do is stroll into one of the island's small harbour bars. Leaning against the bar, your gaze inevitably falls on the historical photos hanging on the walls. They show men fishing for tuna. Huge nets being cast into the sea. Old fishing boats with long spars and lateen sails moored in the harbour, cruising around the island in flotillas. The small town of Carloforte was long a stronghold of tuna fishing in the Mediterranean. The pictures of the Tonnara are world-famous.

The island is correspondingly proud of its local seafaring tradition. Tuna is still caught here in the old-fashioned way. With small boats, large nets and bare hands. There is also a renowned naval academy on the island. Captains, navigators and ship technicians are still trained here today. There is hardly an islander who does not go to sea, who does not also fish and sail and has an almost intimate connection to the sea.

Also interesting:

But of course times have also changed on San Pietro. Modern yachts have long been moored in the marinas in front of the promenade. Catamarans, speedboats, stylish large yachts. Anyone strolling along the jetties today will discover the whole range of modern sports boats that are available in the leisure society of the third millennium.

The trend is well known: lots of plastic, little wood. Lots of horsepower, little manual labour. Cream-coloured sun cushions and tinted windows instead of coarse forecastle boxes and ponied-up planks. The eyes widen all the more when a floating rarity suddenly appears at the back of the Marinatour's floating pontoon. A boat like a contemporary witness that seems to have sprung from the old black and white photos in the bars. A pointed gate that looks like it did a hundred years ago. Beautifully painted, historically drawn and absolutely authentically rigged.

Nothing on board the Gozzo is made of plastic

Even in maritime Carloforte, a boat like this is the exception today. A real-life gozzo that is not just a folkloristic photo motif in the harbour, but actually sails out - and under sail. In other words: under the hot Italian sun, in the midst of the hustle and bustle of modern yachts, there is suddenly a veritable old tuna runabout - as if time had been turned back decades. The boat looks small and elegant. Immaculate in condition. Rustic and yet extremely elegant. The name appears as a white lacquered milling on a mahogany sign: "Luigi Padre". Home port: Carloforte.

A beautifully curved double-ender rocks on its lines, finished in glossy clear lacquer, classic white and Mediterranean turquoise. And indeed, the boat resembles the agile and efficient workboats of the fishermen of the past down to the last detail.

Nothing on board is made of plastic, not a shackle, not an eye made of stainless steel. The superstructure nestles flat on the wooden deck, while the freeboard rises out of the green water. The long bowsprit protrudes far into the harbour basin and the massive mast is braced with ropes in the old fashioned way. The long spar of the rig is particularly eye-catching: the 13-metre-long tail of the old lateen sail points into the sky like a white needle and protrudes aft far beyond the seven-and-a-half-metre-long boat. The Italians refer to this most striking part of the lateen rig as the "antenna".

The boat is a fantastically beautiful wooden construction. A feast for the eyes that could have come straight out of an old silent film. And the boat is still just lying in the water, not even the sails have been struck. But even so, the boat makes an impression. In the midst of the contemporary plastic armada, it resembles a solid original. No chichi, no luxury. This is a classic Mediterranean boat. An honest boat, just like an Alexis Sorbas would sail.

Sailing all-rounder

Similar square-rigged boats are known throughout the Mare Nostrum, from Greece to the Spanish coasts. They were built and sailed everywhere in slightly modified form. In the Balearic Islands they are called Llauts, in Italy Gozzi, in Greece Kaiki. Regionally, this type of boat is often given completely different names. In Sicily, the small displacers are also called buzzu or vuzzu, while in Malta they are called luzzu.

In the past, the boats were used for trolling, lobster and tuna fishing, sometimes also for transporting goods or for ferry trips between the islands. When the lighthouses were still fuelled by oil, the men in such boats even sailed barrels of petroleum to the remote cliffs on which the sea markers stood.

Their characteristics made the small boats sailing all-rounders back then. They offered space for working on deck and stowing underneath. They are stable, manoeuvrable and start quickly. Without a deep keel, they could also navigate shallow waters, often even reaching the beaches and being pulled onto the sand. Thanks to their shallow but wide design, the boats are also quite seaworthy and can hold their own against many a current, even in light winds.

However, these quaint Mediterranean fishing boats are rarely sailed today. The handling of the old scabbard sails is too complex, the trimming and loading with ballast too laborious. Finding a suitable crew is also not easy today. The foresailor not only has to drive the jib, but ideally also lead the long spars to which the mainsail is attached. Depending on the course to the wind, the "antenna" is angled steeply upwards or more horizontally. An art in itself that hardly anyone has mastered today.

Formerly a tuna boat, today more of a bathing boat

Meetings of the old Latin boats still take place occasionally in Stintino in Sardinia. Regattas are also sometimes sailed, with participants travelling from all over Italy, some even from France and Spain. In Sardinia, this is tantamount to a maritime festival: dozens of lateen sails, like white triangles, sailing across the sea. However, such sights have become extremely rare.

As a rule, if one of the pretty Gozzi can still be found in the harbours between Genoa and Sicily today, it is usually used as a bathing boat or chugs couples in love to the blue grottos. There are cushions, awnings and cold drinks on deck, while the tanned captain tells the passengers about all the great things they used to do with the sailing boats. And even as converted excursion boats with rattling diesel engines, the ships are still an eye-catcher in any harbour today.

But woe betide them if they are sailed! Woe betide them if they cross the water with a full lateen sail - just like in the old days when the Mediterranean still belonged to pearl fishers and tuna pirates! At the latest then all eyes will be on them.

Adolfo and his son Luigi Simonetti are on board the "Luigi Padre" this morning. They are one of the few people who not only own a boat like this and look after it, but also occasionally sail their gozzo according to all the rules of the art. The "Luigi Padre" is a so-called "Schifetto Carlofortino", as it was sailed centuries ago, especially on the Isola di San Pietro. The term comes from the word skiff, which generally refers to small sailing boats.

The boat is made of oak, iroko and spruce from Livorno. The solid beams at the bow and stern are made from the strong wood of the olive tree. However, father Adolfo came up with something special for the deck, superstructure and panelling. As he used to sail halfway around the world as a nautical engineer on cargo ships and worked in the shipping industry for a long time, he had good contacts. As a result, he was able to have a load of mahogany shipped to his island. The precious wood came all the way from Peru - especially for the construction of his Gozzo.

The small scuppers in the sloping freeboard are unusual. Small round holes through which water runs on deck when heeling, collects and sloshes back and forth. In the past, fishermen used to put corks in these holes to allow the salt water to accumulate on board and drain away later. A simple and efficient method to keep the lobsters, which they heaved on board with the traps, fresh for as long as possible. While still sailing, the crustaceans crawled around in the seawater on deck until they were sold alive from the pier in the harbour.

Where there used to be fish traps, lead now helps on the Gozzo

The shape also stands out. The bow and stern are strongly tapered. The convex side edges are inclined outwards with a classic length to width ratio of just over 3 to 1. The forward leaning mast is also striking. The long "rod", to which Adolfo and his son Luigi Simonetti are now attaching the large sail, is pulled up with triple-deflected halyards. This afternoon they finally want to sail their Gozzo properly again. Clouds are drifting over the island and a warm mistral is blowing from the north-west. Good conditions for cruising to Isola Piana and taking a tour across the blue and green sea.

Father Adolfo sews new leather panelling on the long spar and cuts fresh lines through the blocks on the bowsprit's rack ring. "It's important to me that the boat sails as if it were original," he says, even if this one can be considered a retro classic. "The next step is to clear up on board and clear the shallow saloon for sailing. Then the two of them strike the jib. The "Luigi Padre" is one of those somewhat larger Gozzi boats that also have a foresail. Afterwards, however, the boat has to be properly balanced: Father and son heave the ballast on board by hand - because where fishermen used to carry traps, bottom weights and fishing gear in the bilge, today several lead bars, each weighing 25 kilos, have to help out so that the boat gains stability with its shallow draught.

And then the time has come. The "Luigi Padre" is ready to set sail. The only thing missing is the crew: six people are needed to optimally operate the speedy latin ship and balance it to the best of their ability high up in the wind.

They set sail at four o'clock in the afternoon. Six cheerful Carloforiners in red shirts chug around the pier against the backdrop of the pastel-coloured town and set sail just behind the harbour entrance. With several men, they hoist the large lateen sail, set the jib and move into position. The six of them are a well-rehearsed team. Some work as mariners, others as ferrymen, and together they have sailed in many regattas and won many trophies.

The Italian flag flies as skipper Adolfo stops the diesel engine and the Gozzo immediately picks up speed. The boat zips off like a feathered flounder with an outstretched sword. Despite its impressive displacement, the boat lays on its side and heads upwind. The lateen sail is set on edge into the wind like a pointed wedge, and the boat promptly makes seven knots and even more with ease. It is not without reason that Adolfo and Luigi Simonetti have won several regattas with it.

Bella Figura under sail

The two sails in their formation are a sublime sight. Dynamic and with flying foot leeches, they soar across the sea like the wings of an old dragon glider. If different rigs were allowed to hold a beauty contest with each other - the lateen rig would pass as a real beauty. Bella Figura under sail: The old Gozzi certainly know how to do it.

Since the time of Christ's birth, this rigging has been the sails of choice in the Mediterranean for many centuries. Galleasses, the ships of the Romans, even the early caravels of the Portuguese were Latin-rigged. It was precisely these rigs that ultimately brought about a miracle in sailing: Equipped with a suitable keel, this triangular and flat sail shape enabled man to cross against the wind for the first time - instead of always being blown off the beam.

A revolution that considerably shortened journey times at the time, made new routes possible and opened up a new dimension to mobility at sea. From then on, sea voyages could be planned completely differently, goods could be transported more efficiently and foreign harbours could be approached in a reasonably targeted manner for the first time. For a long time, this was not a matter of course: for the first time, man was able to wrest distance from the wind - and not the other way round.

Adolfo, Luigi and the others are clearly enjoying feeling for themselves how well the Gozzo sails, how this type of ship still manages to effortlessly pull itself across the sea. The men lean over the edge, cling to the shrouds, and leap from one side to the other when tacking. Although a solid, sturdy boat, the "Luigi Padre" almost has the vigour of a dinghy.

Legendary pizza evening arouses interest in the Gozzo

It is thanks to Adolfo Simonetti, the signore at the tiller, that this beautiful schifetto sails so smoothly, indeed that it exists and was built at all. He started sailing as a teenager and was soon whizzing across the sea off the island in various dinghies. Even during his time as a professional skipper, he never gave up sailing. On the contrary: Adolfo Simonetti was committed to sailing regattas, in the 470 and other modern boat classes. One day, however, years later, he was to sail through what could be described as a "sailing awakening". Simonetti still remembers that "legendary pizza evening" in the north of Sardinia. Together with three experienced sailors and boat builders, he was sitting at the table in the evening with beer and wine when they suddenly launched into a suada about the advantages and characteristics of classic sailing boats. The three of them swore by the qualities of the wood, singing the praises of the beauty of the old, genuine boat building material.

Soon afterwards, Simonetti skippered a friend's boat, which was made of wood. He sat in the boat in the evening, alone, and went out to sea between the islands. The sails were well set, the waves lapped around the hull as the boat glided through the warm wind. Then it happened: "I suddenly felt something that I had never experienced before while sailing." Simonetti suddenly experienced a deep connection, almost a kind of dialogue between the boat, the wind and the sea. "I was literally overwhelmed. A wooden boat like this was actually capable of triggering things that I had never experienced while sailing before. The wood spoke, it was alive. It was as if the boat had a soul. It may sound crazy, but it was almost a spiritual experience."

Then what had to happen, happened. Adolfo Simonetti went to one of the last remaining wooden boat builders on the island of San Pietro and said to him: "The next boat you build will be mine!"

Like an original from the old days

Wooden boat builders have a special job title in Italy. They are not simply called wooden boat builders, but call themselves maestro d'ascia - the masters of the axe. It all started in 1996. They drew up plans based on old originals, procured wood, traditional fittings, blocks and rack rings. And then the mahogany arrived from Peru.

It took the boat builder six months to construct the boat. Simonetti: "I went to the workshop every day after work and followed every step of the process, as the shipyard is just round the corner." He immersed himself headfirst in the finer points of the wooden boat, worked with various paints, learnt about the advantages of brass screws and bronze fittings, dealt with old cracks, rough masts and old-style cut lateen sails.

He wanted his boat, the "Luigi Padre", to look just like the originals from the old days. He even built a tent for the boat on his property on the old salt lagoon. A small workshop where he still maintains, polishes and paints the boat in the winters.

"In the end, it wasn't all that easy," Simonetti recalls today. "A huge amount of time and effort went into the project at the time, as well as a lot of money. But everyone got involved and was enthusiastic. My wife, family, friends and of course my son Luigi. After all, we all know about the tradition of seafaring on the island because we grew up with it."

When the Gozzo finally entered the water, it was nothing more than that: a sailing history book - an original contemporary witness from the long and vivid maritime history of the time-honoured Isola di San Pietro. Only completely redesigned and rebuilt.

Capital of tuna fishing

Tunisian coral fishermen from Tabarka once colonised the Isola di San Pietro in south-western Sardinia. Centuries ago, fishermen set large gillnets in the sea to drive the mighty bluefin tuna into the camera del morte, the death chamber of a complex cage system that reaches down to 40 metres into the sea. For the men on top of the rocking boats, this used to mean hard labour for both sailors and sailors. Of central importance here were the seaworthy and fast gozzos, the traditional pointed creels that exist in various derivatives in the Mediterranean. What they all have in common is the lateen rig, which made it possible to sail upwind for the first time in history and thus revolutionised seafaring.

Technical data of the "Luigi Padre"

- Torso length: 7,45 m

- Waterline length: 7,30 m

- Width: 3,00 m

- Depth: 1,00 m

- sail area: 40,0 m2

- Motor: Yanmar 30 hp

- Year of construction: 1997

- Shipyard: Cantiere Navale Antonio Sanna