It's a good night's sleep in Francis Chichester's coffin. A narrow, cosy hollow covered with dark blue cloth. The English really do call the slightly hollowed-out dog bunk towards the stern: coffin bunk.

"Why don't you sleep on board," Pete Rollason, head of the Gipsy Moth Trust, had said that evening. His offer came in handy. All the rooms in Cowes in the south of England are fully booked for this weekend in early July; 6,000 sailors have flooded the Isle of Wight and over 1,500 yachts want to start the Round the Island Race tomorrow. And instead of spending the night on a park bench, they prefer to slip into a bunk. And this is not just any bunk, this is the bunk of Sir Francis Chichester, perhaps the last great British naval hero - the little watch berth on board one of the most famous yachts in sailing history.

Also interesting:

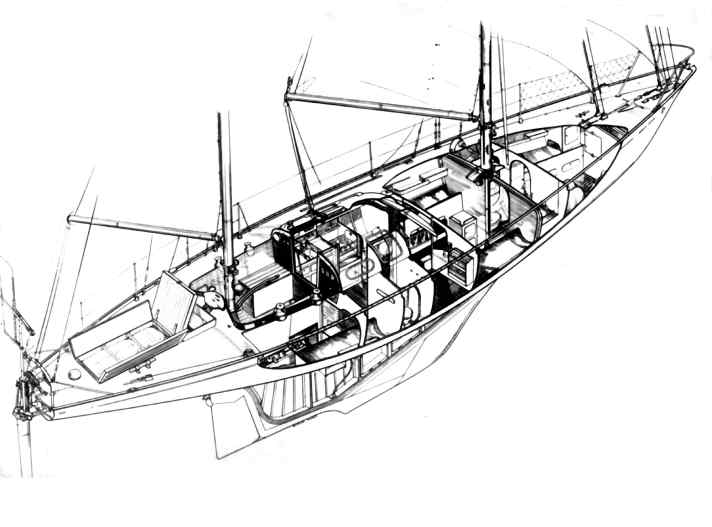

With the "Gipsy Moth IV", a snow-white, 16-metre-long ketch designed by John Illingworth and built by Camper & Nicholsons, Chichester set off on a ground-breaking long voyage almost 60 years ago: the first time a yacht had ever sailed so far across the oceans non-stop. On 27 August 1966, the then 64-year-old Chichester cast off from Plymouth. Sailed to Sydney without ever going ashore or dropping anchor. Stayed there for a good month. And sailed straight back again - non-stop to Plymouth.

When Chichester, who had allegedly been suffering from cancer, docked in England again on 28 May 1967, after nine months and one day, 250,000 people cheered on the pier and the British artillery fired their guns in salute. In Chichester's honour, Tower Bridge was opened in London to the ringing of bells and the Queen knighted him. Sir Francis had secured several records with his legendary voyage - without really having planned it.

"Gipsy Moth IV" makes history

This was the fastest circumnavigation of the world on a small ship to date. At over 8,000 nautical miles, it was also the longest non-stop voyage that a yacht had ever completed: Chichester more than doubled the greatest distance travelled by a single-handed sailor at the time. He also set further distance records for solo sailors with his "Gipsy Moth IV". The sword that Queen Elizabeth then honoured him with is said to have been the same one that fell on the shoulder of the privateer, explorer and vice-admiral Francis Drake 400 years earlier.

Historic premier league, hardly any Neil Armstrong can compete with that. And now lying in this bunk, at the back of the aft ship, on the port side, in this blue cloth. One night alone on board this yacht. Yes, an honour, I suppose you could say.

From the head of the bunk, his gaze falls on the small airguide compass that Chichester always kept an eye on during his months at sea. Even in his sleep, he read the course there. Next to it were the old instruments, which were the most modern available on the market in the 1960s. Anemometer, log, angle of incidence display. There is the narrow companionway into the spartan cockpit. The large, unconventional pipe from the old paraffin heater that runs lengthways through the cabin. In the centre of the saloon is the small red leather stool that folds out. Galley, chart table. The iron hand-held compass in the navigation corner, secured with Velcro. The old radio loudspeaker covered with rattan bast.

Sniff. What does it smell like down here in the ship? Well, it may be my imagination, but it smells like nautical miles. The boat bobs quietly at the pontoon of the UK Sailing Academy, not far from the historic centre of Cowes. Ships and yachts everywhere. At seven in the morning, the harbour slowly comes to life as the sailors arrive. Then the "Gipsy Moth IV" is boarded by Pete Rollason, 48, who as manager of the foundation is responsible for maintaining the yacht. "Did you sleep well?" he asks. "Formidable!"

The "Gipsy Moth" is fast and pushes a lot of position

Next to climb aboard is Dick Saltonstall, an old naval salt hump and long-time instructor. He will be the skipper today and will be beating the "Motte" through the race and through the sea with five guests on board. Out in the English Channel, winds of up to 30 knots are forecast, but Saltonstall, bright red sunglasses on his face, seems deeply relaxed. In response to a guest's cautious question as to whether smoking is allowed on board during the regatta, the Navy man replies: "This is a 54-foot-long ashtray, everyone smokes here."

Saltonstall takes a similarly relaxed approach to handling the ship after chugging out. In the midst of the hustle and bustle of hundreds of masts, he sets full sail and bludgeons the old yacht across the starting line at six knots. Immediately there is a heavy cross against it, the sea is ploughed green and white. The wind is blowing hard, spray is splashing across the deck, the leeward sea fence is shooting through the water. The old yacht is making 6.5 knots, ploughing its way carefree towards the Needles, those rocky needles at the western end of the island that jut out of the sea like shark's teeth.

The famous yacht looks quite unpretentious. It hasn't had much of a paint job, with paint peeling here and there. Faded teak coaming, bronze vents tarnished green, soft, old sails. You would immediately believe it if someone claimed that the boat had just returned non-stop from Australia - and was already heading back next week. No, not a chichi steamer, but a saltwater vessel.

"Almost everything is still in its original condition," says Pete Rollason 2016, who is a keen sailor himself and has travelled around the world twice. "We only had to replace the winches and the mizzen mast." The old mast came from above and broke when they were rammed amidships by another yacht during an earlier Cowes regatta.

The "Gipsy Moth" is fast, soon making eight knots at a good 7 Beaufort. On the wind, mind you, while the sea is constantly gushing over the deck to leeward. Skipper Saltonstall doesn't seem to be bothered by the considerable lean; he doesn't reef, while almost all the other boats have put up one or two reefs and reduced the headsails. The aluminium masts and double stays of the "Gipsy Moth" still have the entire surface area of their old cloths: mizzen sail, main, jib, staysail. Saltonstall: "She can handle it, she's used to completely different things."

Around the world a second time

In fact, the world-famous yacht has had to take quite a beating, even after Chichester's legendary 28,500-mile voyage, which some called the "voyage of the century". After its historic deed, the boat initially ended up in a kind of fenced-in display cage in London's Greenwich district, where it stood next to the "Cutty Sark" as an exhibit on land and lay there as a doomed museum piece - for 39 years. "In the end, there were ice cream tubs and bags of crisps on her deck," says Pete Rollason. "A sad, alarming sight."

When she was to be sold one day, an English business couple bought her to prevent her from going abroad. After all, this was a not insignificant episode in British maritime history. The Gipsy Moth Foundation was then set up - it acquired the ship for the symbolic price of a pound and a gin and tonic. Their commitment to this day: to keep the yacht in good condition and sail her as much as possible; to make her accessible to the public, to honour Chichester's spirit of adventure and to inspire future generations.

As soon as the foundation had rescued the boat, it began to fulfil its mission. Refurbished the "GM IV" - and promptly sent her around the world a second time for her 40th birthday in 2006. It was to be a memorable voyage. Ten different skippers came on board, as well as over 100 crew members of all ages: a colourful gang that was flown in and out for the individual stages. They included children with cancer, ex-drug addicts and former prisoners, as well as millionaires and dukes, who also sailed on some of the passages.

The prominent yacht will be making day trips until 2022

The "Gipsy Moth" visited 32 countries on her second trip around the world and ran aground on a reef in Rangiroa, leaving a three-metre-long hole in her hull. She was salvaged in a hair-raising rescue operation, her destroyed planks of Honduras mahogany were replaced and the hull was laminated over. The "GM IV" survived her second death and sailed on through a by no means dull existence. She caught fire in the Tuamotus and sailed through a 50-knot storm in the Tasman Sea. Princess Anne came on board in Australia and the journey continued. After another 28264 nautical miles and 610 days at sea, the ship docked again in Plymouth. This second voyage is said to have cost a million pounds - but the English were proud of their mission: to keep the name Chichester in honour.

After her return, the strikingly sleek yacht was moored in Cowes, went on tours with guests, sailed to events on the English coast, but also to France, Ireland and Scotland. Famous rugby players and TV presenters were already on board, stars such as Ellen MacArthur, Pete Goss and Mike Golding came and wanted to sail this ship.

And yes, she can do that. In the afternoon, the Needles have long since rounded, the "Gipsy Moth IV" is rolling, pushing and hissing through the open English Channel at eight knots, with the wind now blowing from astern. Waves three metres high are approaching from astern, and dozens of masts and boats are still galloping through the sea to the left and right. The "GM" keeps up in good humour, even with the majority of modern plastic yachts.

Big Roller", Pete Rollason shouts to skipper Dick when threateningly high wave walls roll in from behind. The yacht, as narrow as it is and as flat as its freeboard is, lifts its backside briefly, lets the travelling walls of water pass gallantly under the hull, lies on its side, pulls to windward, only to immediately pick up speed again. They no longer use the old wind steering system, and you can feel the enormous power of the ship at the tiller. When riding the waves, the muscles have to pull hard on the large tiller to prevent it from shooting into the wind. For a long keeler, the boat marches through the sea with astonishing sensitivity.

Better to leave the sails standing for weeks

In the early evening, we are already heading back towards the sea of masts that bends around the eastern tip of the Isle of Wight and now, with a strong current, we head for the finish line off Cowes. The starboard railing cover has long since been torn to shreds because it is constantly dragging through the sea. But skipper Saltonstall is still not thinking about reefing. He doesn't have either of the two headsails recovered and doesn't reduce the size of the main by a centimetre using the furling system on the boom. "With a new rig and new sails, I wouldn't put it past her to make a third trip around the world," he says, looking at the silver water in front of the bow.

Chaos reigns just before the finish line, dozens of yachts crowd into the eye of the needle off Cowes. One tack follows the next, sailing becomes work. Skipper Salstonstall eases the main, tightens up again, picks up a little speed, takes out a little, makes use of every metre of his course right. Two or three yachts come frighteningly close, cut the course and pass just a few metres off the bow. Here and there people shout: "Tack, damn it!"

Down below, everything hangs askew as the "Gipsy Moth" heads upwind for the last anchorage. Ropes and drying cloths dangle in the cabin, and through the large arched windows and skylights you can look far into the sky and see the entire rig. Chichester attached great importance to this unusually open view from the ship. It may have been due to his time as a pilot, when he flew a biplane halfway around the world in the 1930s. His aircraft was a DeHavilland of the "Gipsy Moth" type. He named all his later yachts after it, and he obviously didn't want to do without the cockpit-like view.

The boat is still heeling at 30 degrees, and one wishes for the gimballed armchair that Chichester had installed for his long voyage. He sat in it halfway horizontally in the centre of the cabin, even when his "moth" was lurching violently through the sea. He sat in his rocking armchair and tapped his beer in the middle of the oceans. He had a large barrel of Whitbread Pale Ale installed, complete with its own on-board dispensing system.

As the yacht centimetres the final turn across the finish line, amid a dense crowd of ships, you get the faint impression that the stray moth is longing for the old days. She looks like a well-travelled frigate bird next to most of the other ships. As if to say: no, I'd rather not zigzag around an island. Better to leave the sails on a bow for weeks on end, set a wide course and cruise the seas for months on end. Without big words, accompanied only by the silent applause of the waves.

Technical data of the "Gipsy Moth IV"

- Shipyard: Camper & Nicholsons

- Year of construction: 1966

- Torso length: 16,30 m

- Waterline length: 11,73 m

- Width: 3,26 m

- Depth: 2,83 m

- Weight: 11,4 t

- sail area: 79,0 m²

The "Gipsy Moth IV" is currently undergoing a multi-phase restoration with the aim of restoring it to its 1966 condition. The restoration is being carried out in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. A further circumnavigation is planned.

- More information: gipsymothiv.com

The article was first published in 2016 and has been revised for this online version.