"Anyone who sails is actually always sailing a regatta in some way," laughs US American Steve Frary, a retired businessman and passionate owner of classic Herreshoff boats. Actually, he just wanted to buy a daysailer that could be handled by one or two people and also offer comfort for the weekend. "I didn't fully realise what I had got myself into until I delved deeper into the project."

This project was the museum-worthy restoration of the 12.80 metre long "Arion", no less. After all, it is the world's first large sailing yacht to be made of fibreglass-reinforced plastic. She was launched on 15 May 1951 at the Anchorage shipyard in Warren in the US state of Rhode Island.

Also interesting:

At this time, the wooden boat era still prevailed in Europe. The Seafarer yachts from the USA were not built in the Netherlands until 1958, and Henri Amel began to build the first GRP cruisers in France at around the same time. In Germany, the GRP era did not begin until 1963 with the Fähnrich and Hanseat models.

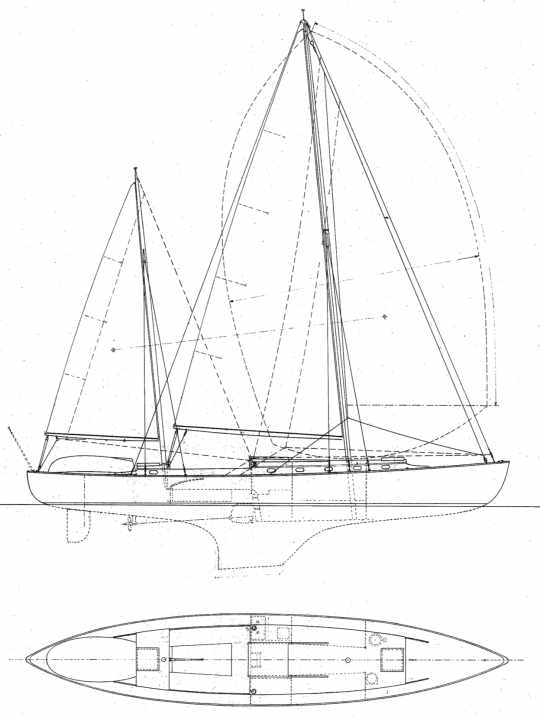

The slender double-ender with the then rare centre cockpit and well-proportioned superstructure was designed by Sidney DeWolf Herreshoff. He lived from 1886 to 1977 and was the son of Nathanael Herreshoff, who as the "Magician of Bristol" revolutionised the design and construction of racing yachts like no other and is considered the most successful designer of all time in the America's Cup. With "Arion", Herreshoff junior proved to be as visionary and innovative as his father, even though his younger brother L. Francis Herreshoff famously derided GRP as "frozen snot".

"Arion" amazed the experts

The order for the ship was placed by Verner Z. Reed, then the commodore of the Ida Lewis Yacht Club in nearby Newport, once the centre of the America's Cup and as such the sailing capital of the United States. "Built from maintenance-free Dyeresin, this is the world's largest yacht

made in one piece from GRP," enthused one magazine article. "Smooth as an eel and tough as steel, there's no twisting or leaking. The design, which extends service life and reduces maintenance costs, makes this the boat of the future," it continued. There was a spirit of optimism in America. Resourceful boat builders such as Carl Beetle (father of the Beetle Cat) took up the shooting iron to convince people by opening fire on a GRP hull from which the bullets ricocheted.

The experts were naturally amazed at the construction method of "Arion's" narrow hull, which did without traditional frames and stringers because the rigidity was derived from the shape and the hull material of solid GRP, the thickness of which varied greatly. The deck, coachroof and cockpit were made of waterproof plywood covered with fibreglass mats and pigmented resin. With a weight of just 4.8 tonnes and a sail area of 52 square metres, "Arion" was a front runner in regattas almost straight away.

Shipyard boss Bill Dyer, who lent his name to the resin used, praised his work: "The hull is quite flexible, not brittle ... And it is very easy and inexpensive to repair." It was also resistant to fouling and pests such as termites and worms, which plague many wooden boats. With these various advantages, the commercial success of "Arion" was actually out of the question. But perhaps the boat was too extreme, the innovations too many, because things turned out very differently.

GRP experiences upswing, but "Arion" is parked

Dyer's prophecy that low-cost series production using composite materials would create a boom, however, was absolutely correct. With robust and affordable GRP boats such as the forefather of the beach cat Hobie Cat 16 or the later even Olympic single-handed dinghy Laser, millions of average earners found access to the water and to sailing in the following decades. Only "Arion" remained a one-off. Boats had to meet new demands for space and comfort, which meant that the slim "Arion" was left out in the cold and found its supposed last parking space in a pasture on Cape Cod.

It was there that boat builder Damian McLaughlin, known for his multihulls, which he built according to the plans of Dick Newick, Steve White and James Wharram, but also more traditional designs by Sparkman & Stephens, Herreshoff and Chuck Paine, discovered them. "I wanted long, slim and light," confesses McLaughlin on his website. "Beauty was also a desire, but this characteristic is inextricably linked to other aspects of the design and can't just be mixed in later." According to McLaughlin, he actually wanted a larger version of L. Francis Herreshoff's "Rozinante", a classic 8.53 metre ketch with a canoe stern that is also well worth seeing.

He knew about "Arion", but not about her relatively good structural condition, which was established when she was rediscovered. The robust construction made of solid laminate and the fact that old GRP boats are not sought-after recycling objects saved the ship from the slaughterhouse.

Resurrection of an antique

McLaughlin bought the Hulk and set about restoring her, for which he had the hydrostatics and dimensions for a new rig calculated. The interior, deck, superstructure, keel and aft cabin were rebuilt before the boat floated again in June 2001, almost 50 years to the day after it was launched. "For me, it was the resurrection of an antique, an archaeological excavation and the bringing together of everything that makes the perfect classic cruiser/racer for me," he explains. He is delighted with the boat's characteristics, which became apparent during the restoration, tuning and sailing. He stiffened the 7/8 wooden rig with carbon fibre and fitted backstays to be able to put more tension on the forestay. He also gave the mainsail a little more surface area and modified the rudder.

Although there is only headroom on deck, the boat is anything but spartan. Four berths, two in the main cabin and two in the aft cabin, plus a galley with cooker and fridge provide sufficient comfort, even from today's perspective. However, this is not a priority for McLaughlin, as a good ship must also move well, he says, and explains that "Arion's" log sometimes kisses 14 knots in strong winds under reef. "She is very fast, with a pleasant sea behaviour, and sails almost by herself, without rudder pressure. And in the harbour, she manoeuvres like a small dinghy," assures the boat builder. "At times the batteries were dead because I never needed the engine, but always docked and cast off under sail."

As it turned out, "Arion" was an excellent calling card, as a customer soon got in touch to order a copy of the boat from McLaughlin - but in wood. In a way, this turned the story on its head. Normally, it works the other way round, for example with the Drachen, Folkeboot or Herreshoff's Alerion, all wooden boats that were later produced in plastic. Under the name "Walter Greene", the replica of the "Arion", which was a tad lighter and faster, caused a furore at local regattas.

Establish best condition - budget doesn't matter

Meanwhile, the original "Arion" started a new chapter with its new owner. Steve Frary bought the boat from McLaughlin and brought it to the Snediker Yacht Restoration shipyard in Pawcatuck, Connecticut, which specialises in high-end restorations. Frary was an expert, as he had already worked on Nat and L. Francis Herreshoff boats there. Shipyard manager David Snediker and his crew were given the task of restoring the venerable "Arion" to top condition, regardless of the budget.

The cabin superstructure was replaced with a new one made of Sitka Spruce and plywood, and Snediker installed a luxurious interior made of teak and cypress wood after replacing all the tanks, the auxiliary engine and the entire pipework system. "The hull construction of pigmented resin and narrow fabric strips is very interesting," Snediker found. "The laminate thickness increases from 6 millimetres in the deck section to almost 45 millimetres in the keel. We also found spruce wood between the keel and ballast as well as keel bolts made of monel" (a nickel-copper alloy).

So many new features also meant more weight on board. "Arion" now displaces 5.35 tonnes, says Frary, but she can still sail fast. "More than eight knots is no problem at all," says her current owner, who mainly takes the boat on day trips with the occasional overnight stay - or the odd regatta. It is only in choppy water and strong winds that the pleasure becomes rather damp due to the low freeboard, a characteristic of many classic yachts.

A boat heralds a turning point

On the other hand, according to Frary, "Arion" was "300 per cent oversized, which means she could easily last for another 100 years". Although no further examples were built, Bill Dyer was right to take the risk of building a 12.80 metre long performance boat from the composite material, which was still untested in yacht building and was the largest of its kind at the time and is still a reminder of the beginning of a new era today.

The future of the famous yacht also seems to be clear. Frary would like to bequeath it to his two children Elizabeth and Nathaniel, who have sailed with him from an early age and are therefore very familiar with the history that influenced this design. Sid Herreshoff's son, America's Cup veteran Halsey, completed his final year of school in 1951 and was already involved in the trial runs. A few years ago, he made a white oak tiller from his father's original plans as a gift for "Arion's" designated future owners.

Fortunately, it seems that Steve Frary knows only too well what he has got himself into. The boat that made history by ushering in a new era - the current era - in boatbuilding is far from reaching its final chapter, even after more than 70 years.

GRP: A material makes history

Glass fibres, which were already used in their original form as glass filaments for decorative purposes in ancient times, now dominate boatbuilding worldwide in combination with plastic resins, particularly in large-scale production. The decisive development of the materials took place in the USA before and during the Second World War, driven by resourceful engineers such as R. Games Slayter or Dan Kleist at the manufacturer Owens-Illinois, but also favoured by many a lucky coincidence. Initially, the material was only used as a filter material and insulating wool, but constant improvements made it possible to weave these long and soft fibres into cloth that was tear-resistant and did not crease.

It soon became apparent that glass fibres soaked in resin were easy to shape and, once hardened, were not only lightweight but also extremely robust. This made it possible to replace plywood and metal parts on warships, which meant that, among other things, the aluminium previously used in aircraft construction could be saved. Glass fibre composite also has many favourable properties: it is waterproof and resistant to acids and alkalis, does not conduct electricity, resists mould, shrinks, expands and does not rust.

Naturally, there was good business to be made with this new miracle material. This is why Owens-Illinois entered into a joint venture with Corning Glass Works in 1935, which resulted in the subsidiary Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation, which mainly produced GRP parts for the US military during the war years (such as panelling for radar antennas) using the complex autoclave process, which works with heat and pressure.

The next step towards mass production came in 1943, when American Cyanamid launched the first two-component polyresin, which enabled curing at room temperature and thus simplified and reduced the cost of production.

After the war came the boom in civilian applications, led by fishing rods made of GRP and soon also leisure boats, the development of which began in the Midwest of the USA. Ray Greene, the son of a chemist and himself a qualified engineer, earned an extra income while studying in the 1930s by building wooden sailing boats, but dreamed of making them out of plastic. In the beginning, he made model boats out of melamine and urea-formaldehyde resins, the hulls of which he reinforced with canvas and fine wire mesh.

When Owens-Corning began selling fibreglass mats for civilian use, Greene had his solution and set about constructing a 1:1 scale dinghy. He was able to save himself an autoclave because he knew how to organise enough of the coveted, but at that time still heavily rationed polyester resin, with which he soaked the fibreglass cloth before placing it in the hull form and thus fabricating a usable dinghy.

Others followed his example, but the product quality was not consistent. For example, the first GRP boat builders had to learn that releasing a hull or part from its mould worked much better with a suitable release agent. Companies such as Anchorage Plastics, which owned the Anchorage shipyard that built "Arion" in 1951, developed the necessary expertise for large orders from the US Navy before moving into the production of leisure boats made of GRP.

Technical data of the "Arion"

- Designer: Sid Herreshoff

- Shipyard/year of construction: Anchorage/1951

- Construction method: GRP/hand lay-up method

- Torso length: 12,80 m

- Waterline length: 11,55 m

- Width: 2,46 m

- Depth: 1,67 m

- Weight: 4,76 t

- Sail area on the wind: 52,2 m²

- Sail carrying capacity: 4,3

The article was first published in 2021 and has been revised for this online version.