- Introduction of the 60 National Cruiser in 1923

- Renaming from "Resolute" to "Stromer"

- Project takes longer than expected

- Templates and a 3D scan of the keel

- The new ship is to sail regattas

- One with the "Stromer"

- Restoration - fresh cell treatment after 100 years

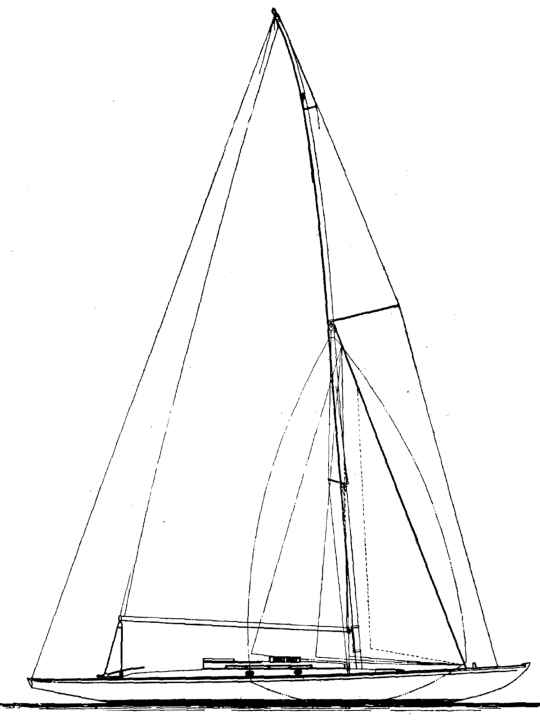

- Technical data of "Stromer"

Text by Luisa Conroy

The first season after its restoration lasted only a short time for the 50-passenger sea cruiser "Stromer". The ship only left the shipyard at the end of July. Since then, the crew has been looking forward to the Ringelnatz Cup, which brings the regatta season at the Potsdam Yacht Club to a close at the beginning of October.

But it happened on the very first cross: "She came in behind my genoa and I couldn't react," reports owner Lutz Müller. "She" was another participant with her Maxi Fenix. When the bow of her boat hit the "Stromer" on the port side, not only did the mahogany of the outer skin crack. It also dashed the owner's hopes of finally having some peace and quiet from the shipyard after three years of restoration work. For so long, Müller had dreamed of spending his summers on the water in peace with this ship.

His story with the 50cc sea cruiser began in 2006, when he saw it for the first time on the jetty of the Seemannschaft Berlin association. At that time, it was still called "Resolute" and was rarely sailed. "It was one look," recalls Müller, "then it was like that. I had to have that ship."

More articles from YACHT Classic:

At first, he didn't even realise what a rarity he was looking at. The nautical cruiser was once built by Heidtmann in Hamburg as a 60 National Cruiser with the sail number A3. And the local Wannsee, where Müller has been sailing Soling for many years, is not only the home of this boat. The lake is also the birthplace of the National Cruiser classes as a whole.

To be precise, the idea even originated in Müller's home club, the Potsdam Yacht Club. At the beginning of the 20th century, sailing on inland lakes primarily took place on the smaller metre-class yachts, which were not only expensive to buy, but also barely developed below deck and therefore completely unsuitable for cruising. The idea of a national cruiser class therefore matured in the skipper's parlour of the Potsdam Yacht Club. The ships were to be affordable, raceable, suitable for inland lakes and also offer the necessary comfort for longer cruises.

Introduction of the 60 National Cruiser in 1923

After some resistance from the Imperial Yacht Club, the Potsdam Yacht Club's application was finally approved at the 20th Sailing Convention. The result was the 45 National Cruiser for inland lakes and the 75 National Cruiser for sea areas, with the number representing the sail area in square metres.

Over the following years, many 45s and 75s were built, but there was one problem: the 75 proved not to be a particularly seaworthy boat. For inland waterways, on the other hand, the beautiful boats with their low freeboard were again too large. For this reason, the Grand Ducal Mecklenburg Yacht Club and the Berlin Sailing Club applied for the introduction of another cruiser class in 1923: the 60 National Cruiser.

The class found many fans. For example, "Yacht" wrote that "the best characteristics of the skerry cruisers were harmoniously combined with those of the later seagoing cruisers" for the 60 National Cruiser. According to yacht designer Paul Francke, the 60s were "the most elegant and sleekest of the national cruiser classes due to their long overhangs". The surprise was all the greater when the 60 National Cruiser was declared an age class just five years after its introduction.

As a result, only 16 examples of the 60 National Cruiser were registered with the DSV at the time of its marriage, five of which sailed under the banner of the Potsdam Yacht Club alone. This included the A3, "Stromer II". Like most of her class, she was re-rigged in the middle of the 20th century to become a 50-boat cruiser. And Lutz Müller fell in love with this very sea cruiser in 2006.

Renaming from "Resolute" to "Stromer"

The owner at the time was delighted with the interest in her boat and invited Müller to come on board. Today, he sits in the cabin of his boat and points to the small cupboard at the front of the boat. "There was liqueur from this cupboard and I told her that if she ever wanted to sell it, she should let me know."

She wanted to - almost 13 years later. After an accident, the previous owner agreed to sell. But it was not an easy separation, as the elderly lady had built up a strong emotional connection to her ship over the years.

The farewell was celebrated with a champagne evening in a hotel on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, and the previous owner acquired the lifelong right to sail on the sea cruiser. Müller had no problem with this, and the rest of the purchase went smoothly. Only the planned renaming back to the original name "Stromer" caused concern, he explains. When the previous owner heard this, she reacted with shock and predicted: "The 'Resolute' will fight back."

And that's how Lutz Müller, who had mainly sailed Soling until then, found his dream boat in 2019. The fact that "Stromer" was a classic was not a decisive factor for him, as he explains: "I never really had a passion for classic yachts. But I do for these. It's like falling in love, you can't explain it either."

Project takes longer than expected

When Müller talks about his passion for his boat, a smile flits across his otherwise serious face. A joy that may explain why, on this autumn morning, he talks unashamedly about the odyssey he has been on with this yacht. A time characterised by financial burdens, health and private problems and ever new construction sites on a ship that was supposed to be afloat again after the first winter in the shipyard. But in the end there were two more winters and two cancelled sailing summers.

At the beginning, no one had expected the project to take so long. After buying it, Müller and a club mate took the 50-metre sea cruiser to the shipyard in Potsdam. Here, the ship was examined intensively and an initial offer was made. The idea: The underwater hull of the GRP-covered hull was to be sandblasted and refurbished, and the laminate on deck was to be removed and a new one applied. Finally, the visibly rust-ridden floor cradles were to be replaced.

So the boat builders set to work. However, it gradually became apparent that the almost hundred-year-old boat had not been professionally maintained for a long time. "For years, it had only ever been painted on the surface, and underneath it was rotting," summarises Müller.

This was already evident when the deck laminate was removed. When this was applied, neither the fittings nor the coaming had obviously been removed, and so "Stromer" was now rotten in all the places where water had been able to enter over the years. The top hull plank, although made of teak, had rotted over time, as had some of the larch planks underneath. The water that had entered at the bow fitting had in turn affected the stem, and the stern looked the same.

Templates and a 3D scan of the keel

But it wasn't just the rotten spots on the hull that dragged out the project. "The owner became more and more involved in the project," says the managing director of the Potsdam shipyard where the restoration was carried out. Understandable, he says, as the boat and owner first had to get to know each other. Müller remembers this time and says: "I wanted a boat that I could sail for a long time. After the first surprises had emerged, I also wanted to look in other places to see what we could find under the surface."

Müller had had a strange feeling about the keel for some time. "This was an area that we were unable to assess properly during the original inspection," explains the shipyard manager. "A lot of things around the keel had rotted away and been replaced by casting compound." The question therefore arose as to the condition of the floor cradles and keel bolts, and after a long back and forth as to whether X-rays of this area would be worthwhile, the decision was made to simply remove the ballast completely.

Before that, however, templates and a 3D scan of the keel were made. This was not so easy: because a large part of the bilge had been filled with cement and laminate to keep the ship watertight, it took the shipyard several drill holes to get to the keel suspension. In addition to a whole lot of grout, the boat builders actually found corroded floor rims and bolts. "I remember standing next to the boat with my son," says Lutz Müller. "We asked ourselves: 'Are we going to leave it as it is or are we going to renovate all the deadwood, including the keel suspension and rudder bearings?" And like so many times before, they decided in favour of renovation.

The new ship is to sail regattas

Müller admits that the restoration was sometimes a great challenge. "Several times it felt like it would never end," he says. "But do you want to stop halfway? No, I couldn't do that."

Did Lutz Müller know what he was getting into when he bought "Stromer"? "You've heard what can go wrong with such old ships," he replies calmly. But he hadn't expected the extent of it. It wouldn't have changed anything anyway. "I wanted the boat, no matter what."

The keel was therefore removed and repaired. The boat builders rebuilt the aft section from oak. The corroded cradles were refurbished and partially replaced with stainless steel ones, and the deadwood and mast track were also renewed. The restored "Stromer" is now a jigsaw puzzle of the centuries under the exposed laminate with which it was covered at the end: Hundred-year-old wood nestles against younger wood, old and new wings connect the restored keel to the hull. And perhaps that is the luxury of restoration: new materials and techniques keep the old boat alive.

However, Lutz Müller is not a full-blooded fan of classic boats; he wanted his new boat to be able to sail in regattas. "Everything else is a bit boring," he says as he steers his "Stromer" across the Wannsee. The furnishings on the 50-boat nautical cruiser reflect this binarity. New, colourful sheets run across the traditional deck and modern halyard stoppers are attached to the wooden mast. Müller explains why: "I told the shipyard to install parts that allow for a modern process."

Müller's crew is responsible for this process and, just like the equipment, is a colourful mix. There's Harry, who actually sails a Soling and otherwise doesn't have much to do with classics. There's Jens, who owns a classic 20 dinghy cruiser himself. And finally Claus, who is known in Berlin and the surrounding area as a classic enthusiast and has been a member of the Friends of Classic Yachts for 25 years. He is also the one who sometimes expresses amazement at Müller's handling of his classic yacht. "But you just stuck your flag alphabet on here like that," he suddenly blurts out in the middle of the cruise. He points to the companionway. Müller looks surprised. "Can't I do that?" he asks innocently. They both grin.

One with the "Stromer"

And yet this ship on the Wannsee seems strangely harmonious, despite the colourful decor and the motley crew. On board, they talk about past and upcoming regattas, the chat group that needs to be set up to organise the next season and the T-shirts they want to print.

Only once does the crew seem briefly awestruck by the age of their yacht, once does the 99 years of sailing that it symbolises seem clear: when a Viking cruiser from 1947 appears next to them. While the helmsmen shout and try to find out the age of the other boat, a harmonious picture emerges on the Wannsee: two classic wooden yachts on a trip on the Wannsee. The crew on board the "Stromer" visibly realise that they were both used by sailing enthusiasts over 70 years ago.

Müller steers his yacht across the local lake, completely at peace with himself. The stress of the last few years, the extensive restoration work, the separation from his wife, a major heart operation - it all seems forgotten when he is allowed to take the wooden lady out. He was immediately at one with the "Stromer", says Müller, when he was allowed to transfer the boat for the first time: "It just belongs to me." The 77-year-old still works, but now primarily to finance the boat. However, he rarely thinks about the repairs or restoration when he is sailing, he says. "You have to enjoy it for now," says Lutz Müller, and a rare smile flits across his face again.

But unfortunately, the next day, disaster struck. He was full of rage after the collision at the Ringelnatz Cup, says the owner. He felt depressed the whole day. Was that perhaps the "Resolute's" revenge? He laughs. "I don't think so!" He sincerely hopes that the "Stromer" will be swimming again in the spring. Then it would have cleared this hurdle in time, because "Stromer" will be one hundred years old in 2024.

Restoration - fresh cell treatment after 100 years

After the purchase five years ago, the current owner had the ship, which was built in 1924 as a 60 square metre national cruiser and re-rigged as a 50 square metre nautical cruiser after the Second World War, inspected. At that time, the hull and deck had been covered with plastic for some time. Water had nevertheless made its way to the wooden structure in various places. A shipyard in Potsdam was commissioned to overhaul the outer skin and structure, such as the stem and sternpost, stern beams, frames and frames. Many of these components had to be completely replaced. The steel composite components in these areas were partially replaced with stainless steel ones.

The bow and stern sections also had to be completely rebuilt. The larch shell planking had also suffered and had to be replaced in places. The iron ballast keel was sandblasted and refurbished, and the deadwood and keel beams were replaced. In the process, "Stromer" was also fitted with new stainless steel keel bolts. Neuralgic areas such as the rudder system, jib and rigging spars were also overhauled. Visitors to the Boat & Fun Berlin water sports trade fair were able to see for themselves that the work was worthwhile, as "Stromer" shone like a new boat once again.

Technical data of "Stromer"

- Shipyard: H. Heidtmann

- Year of construction: 1924

- Length: 12,50 m

- Waterline: 8,90 m

- Width: 2,65 m

- Depth: 1,65 m

- Displacement: 6,2 t

- Mainsail: 36 square metres

- Fock: 10 square metres

- Mainsail: 48 square metres

The article first appeared in YACHT Classic 2/2024.