There are these ships that you simply cannot walk past on the jetty without stopping. Even those who only notice "Neptune" out of the corner of their eye are magically drawn to it, stop and look reverently. If you watch the hustle and bustle in the harbour, this is exactly what happens again and again.

The immaculately varnished teak deck and cabin roof gleam in the sun in an almost amber colour. Just like the mast with diamond stays. The beautiful white-painted, curved, pointed-gate hull with its pretty deck step to the bow and the stern that joins up again aft unmistakably signals the roots, which are reminiscent of the classic Danish workboats of the 19th and early 20th centuries that every Danish sailor knows and associates with the area. No sea fence disturbs the aesthetics of the very tidy deck. Bronze winches, skylights, an artfully spliced white railing that replaces a rubbing strake - a feast for the eyes at its finest.

What is lying here is one of only three boats left in the world in the premier class of the Danish pointed-gear regatta scene: a 55-class pointed-gear boat. As special as the boat is, so too is its construction history.

"Neptune" was built in the vegetable garden behind the house

The Danish owner Bent Okholm Hansen, whom we meet on board, tells us. "My father built the boat himself in the garden behind the house for seven years from 1964. It's a design by M. S. J. Hansen, one of the three big names in the pointed-gear scene (see below). My father was very fond of his boats. He already had an eight-metre pointed gunboat by Hansen, but not a class pointed gunboat, but the 'Springer' design. He had the hull built by a shipyard at the time, and then he did all the fitting out himself," says the tanned 72-year-old Dane cheerfully. He spent the whole summer sailing on the Baltic Sea in the dignified heirloom, which he has now been sailing for 30 years, mostly with his wife Inge or single-handed.

The 55er pointed creels were the largest of the six pointed creel classes from 20 to 55 square metres and had their heyday from around 1920 until the 1950s. Introduced gradually as regatta classes by the Dansk Sejlunion at that time, around 300 boats were built, probably over a thousand similar ones, and not according to the class-compliant measurement formula. The number describes the sail area of the boats, with the 55 being the top class with a hull length of almost ten metres.

Constructor Hansen secretly investigated whether the builder was good enough

And truly, "Neptun" does indeed look regal. The cockpit is almost expansive for a pointed gate, and even the two-metre YACHT editor sits below deck with so much space above his head that you wouldn't think you were on a ten-metre classic. "The boat really was huge by the standards of the 1960s," says Bent. "But it was my father's dream boat because he had helped build a sister ship to the 'Neptun' for a customer during his time at the shipyard before the Second World War."

It was my father's dream boat. He had helped build a sister ship and fell in love with the Riss"

His father was a carpenter, but was working for a shipyard at the time. He therefore wrote to the designer and asked to buy the drawings. But Hansen was a perfectionist who wanted every detail to be realised as he had planned. The idea of a self-builder constructing his own crack seemed risky to him. So he secretly travelled to Kalundborg, where Viktor Okholm Hansen lived, and discreetly enquired in the town whether he had the technical skills to implement such a project.

The answers pleased the great master, and so an agreement was reached, even though Viktor asked for some individual changes to the deck compared to the sister ship: no full-length mast, the cabin roof completely continuous instead of with a small working cockpit at the foot of the mast. Hansen, who is actually considered to be stubborn, agreed, and Viktor then bought vast quantities of wood, which he first left to dry in his garden at home for over a year.

The construction period of the "Neptun" was family time

This is often where stories begin that end with hardship, broken marriages and neglected children. But not in the Okholm Hansen family: "My mum always said that the construction phase was the best time of her life!" Her husband was at home a lot, working as little as necessary to earn a living at the nearby power station, and "Neptune" slowly grew up among the raspberry bushes in the garden. He was happy all round, and in the summer he left the building site alone and went sailing with his wife and Springer.

"The amazing thing is that my father really did almost everything on his own. My brother and I helped when he needed a second hand." For example, when he needed to get one of the pieces of wood out of the homemade steam box for bending, or to make a complicated cut. But that was it. He even moved the seven-tonne boat from the garden to the road on his own, casting the three-tonne lead keel himself in a wooden mould lined with chalk and buried in the ground. How did he do it? That's still a bit of a mystery to Bent to this day. In 1971, the big moment arrived: "Neptune" glided into the water and his son Bent, now a goldsmith, forged the letters for the name. Designer Hansen did not live to see the launch; he died during the long construction period.

Many lovingly crafted details

The fact that his father was a carpenter is reflected in many, sometimes almost playful, details on board. For example, the tiny cupboard doors in the cockpit, behind which the engine controls are concealed.

Or the drawer in the footwell in which the steering compass is concealed. If it was needed, the drawer was opened, otherwise it disappeared. The cockpit looks extremely tidy, almost clean. And the compass was not used that often: "Neptun" almost always stayed in Danish waters, the furthest trip was probably once up the Swedish west coast.

Bent's father spent twenty happy years on the boat, then died after a short illness. Not without giving his son some final instructions on his deathbed: "His last words were that I shouldn't forget the antifreeze for the engine!"

Because one thing was clear, the ship should stay in the family if possible. No problem for Bent, who in the meantime had gone from goldsmith to steel shipbuilder, then house-building entrepreneur, in between becoming an engineer and finally a teacher.

"Although I never sailed on the boat with my father and was long out of the house by the time it was finished, I spent half my childhood in his workshop. I love making things with my own hands!" So they were both happy.

Never a refit, yet outstanding condition

He and his wife sell the Sagitta 26, which they own at the time, and take over "Neptun" - along with a strict maintenance plan: "The ship comes out of the water at the beginning of October, under a tent, and then I work on the boat for about four weeks," says the 72-year-old, beaming. You can tell that the Dane has bumblebees up his arse, is bursting with energy and sees the work as a pleasure, not a burden. It's been like this every autumn for 30 years. Help? Unnecessary.

As a fellow sailor, I used to get seasick. When I had a boat myself and was in charge, it was blown away

Anyone who comes on board "Neptun" immediately realises just how much work is involved: even after a discreet search and even behind lockers and floorboards, we don't find a single black discoloured spot in the wood on board, no dents, no scratches, no nicks in the paintwork - nothing at all. It shines brightly everywhere. The boat with larch planks on oak frames and stringers looks like it has just been refitted. But it hasn't been refitted once in its 52-year life to date. The underwater hull, carvel-planked, still has no epoxy coating or similar lifejackets, as many classic boats of this age have.

"If you look after the boat consistently well, a refit is not necessary. We've also never had a grounding or major damage. It's just carefully built!" explains the Dane almost apologetically.

To achieve this, almost the entire boat is sanded down every year and coated with single-component paint. Only a few areas last two seasons. The teak deck is treated every year with a Coelan varnish that has anti-slip properties. Bent strips the underwater hull every twelve years. So much for sustainability in boatbuilding.

But now we finally want to find out how such a jewel sails. The first surprise comes when we cast off. The boat has a bow thruster! It turns out that the Dane loves his boat, but as an engineer he always adapts it to his needs and those of his wife Inge with his own solutions.

The heir customised the rig to his needs

"In windy conditions, the long keeler with the original 22 hp engine (Sabb) is difficult to manoeuvre single-handed in the harbour, so I retrofitted it." Nine years ago, at 63, he also made concessions to his age in terms of sail handling: the fully battened main is now rolled around the wooden boom electrically by motor, and in rough seas he could no longer and no longer wanted to set the cloth on the mast. The genoa on stays has been replaced by a furling headsail. However, a second stay still allows other sails to be set. "And I had to shorten the boom by over a metre. The main had so much surface area, the rudder pressure was often just too much for me, and sometimes I could only hold it with two hands."

Anyone who sees the huge tiller can guess what kind of forces Bent is talking about. The mainsail became smaller, but he enlarged the genoa slightly. In terms of sail area, the 55 actually became a 45-point sail, but it's certainly better than not sailing, because the Dane, who lives in Odense, loves his days on "Neptun". Last year there were 57 of them, and that's saying something for the Baltic summer of 2023. Once the sail is set, "Neptun" leans just a few degrees to one side in a light wind of perhaps eight knots and marches off. As if on rails, the long-keeler is good-natured and true to course, as is usual for such ships. If you hook the tiller briefly into the comb cleat underneath, you can leave the boat to its own devices for quite a long time.

Bent, on the other hand, is almost irritated by the unfamiliar co-sailor in the cockpit, who disrupts his routine, well-worn single-handed routines. His wife often struggles with seasickness and is therefore happy to let him sail alone.

The crew doesn't have much to do, "Neptune" sails as if by itself

The cockpit is simply huge for a topsail, and even a regatta crew of four would not get in the way. This is also due to the mainsheet traveller, which is cleverly moved over a massive stainless steel bracket integrated into the sprayhood on the roof. This means that the cockpit is not divided, as was often the case in the past. A crew wouldn't have much to do anyway, "Neptun" is a typical cruising boat without a lot of fine-trimming features such as line-adjustable centreboards or the like.

A few gusts of rain pass through. The top gate calmly acknowledges this with a little attitude and accelerates gently but steadily. Upwind, you can feel the rudder pressure of the attached blade somewhat, but pleasantly. As is typical for such boats, the tack needs to be made with a strong rudder angle, and of course the manoeuvre is somewhat slower compared to modern boats. But let there be no misunderstanding: "Neptun" and her owner have also won classic races in their Sturm und Drang years, so the boat is by no means slow.

First the rain comes with the gusts, then the calm. We motor back into the harbour and disappear below deck. What was Bent's best or furthest journey with "Neptun"? "I'm like my father: when I'm on the boat, I'm happy and content, I don't need to travel far at all." In 1986, he took a one-year sabbatical with his wife and two sons in a converted Mercedes van through southern Europe and Africa, and later travelled halfway around the world for projects, visiting Asia and Latin America. He apparently no longer needs to see the world by boat.

Spitzgatter should be simple, affordable boats

The spacious saloon is simple but elegant: the teak and mahogany interior is clear, and the large compartments behind sliding doors and light-coloured upholstery give it a pleasantly airy feel. There are classic slim paraffin lamps, simple curtains and windows with plain wooden frames instead of expensive bronze. At the time, pointed gates were intended to be simple, affordable boats, hulls made from inexpensive local wood, the mast simply a tree. The minimalist interior design fits in perfectly. Only the galley is a little out of the ordinary. A white, standard household 230-volt refrigerator looks like a foreign object. But it is practical and is powered by an inverter and three batteries when travelling. And a stainless steel sink with an integrated two-burner gas hob found its way onto the "Neptun" after the father's death.

The immaculate deck beams, here and there a glimpse of the planks with the beautiful copper rivets - it is simply fresh and cosy, nothing like the heavy, dark salons of many a classic yacht.

In the foredeck, the round stainless steel diesel tank is suspended directly above the owner's triangular berth in full view. "My father installed it there because pointed gates with the round stern are often too stern-heavy with four people in the cockpit. The tank balances this out well," explains Bent.

The 14 side windows and two skylights in the foredeck and saloon provide plenty of light, but can only be opened as a whole on one side. The individual glass panels are fixed. Father Viktor liked this better than the hinged or sliding hatches.

The "Neptun" is a lifelong dream of the builder

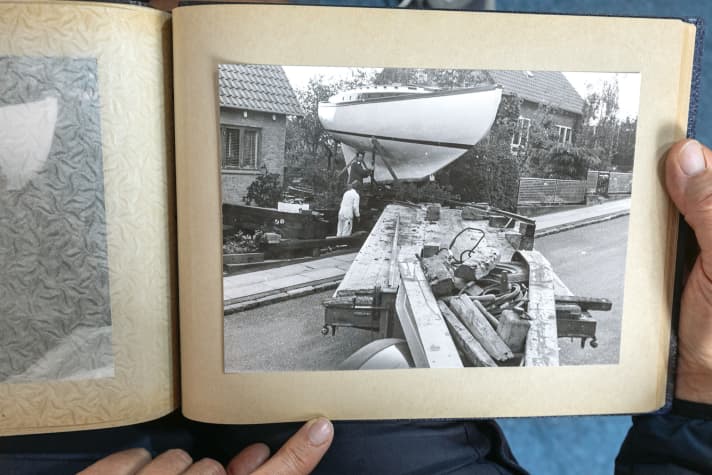

Over typical Danish Frokost Smørrebrød, we sit together comfortably with our wife Inge, who has joined us, and leaf through the photo album of the construction of the "Neptun", first in black and white, then in colour due to the long construction period. The frame is growing in the garden among the raspberries and vegetables. Father Viktor works on the hull and deck with a pipe in the corner of his mouth. The lead keel is fitted. The boat is loaded onto the low loader between the house and the garden. Launching. A man who seems happy to be realising the dream he has carried in his heart for more than twenty years.

"That was one of my father's strengths: if he had a goal in mind, he simply worked towards it constantly. He had no doubts about achieving it. And he also gave us that freedom," says Bent. As a teenager, he wanted his own boat, so he simply built his own OK dinghy out of plywood next to his father in the workshop. He had enough time beforehand to look over his shoulder.

Chance meeting with the sister ship

"When I wanted to leave school after year 7 at the age of 14, my father just asked me: 'Have you really thought this through? I said yes, and that was the end of it for him and I started training as a goldsmith." It gradually becomes clear where Bent gets his consistent determination and enjoyment from working on his own and why he is so closely connected to his boat.

And then, in 2021, chance had a very special moment in store for him: While he was moored in Frederiksværk during a cruise, the second 55-point tackle still in existence in Denmark, the Aage Utzon design "Undine" from 1936, suddenly moored next to his "Neptun". Boat builder Ebbe from Marstal had just refitted it for his retirement. Then it was Bent's turn to stop at the jetty and marvel in awe.

Spitzgatter triumvirate

When the boats gained a foothold as a regatta class in the 1920s, the Danish designers Aage Utzon and Georg Berg were the two key players in the class, with M. S. J. (Marius Sofus Johannes) Hansen joining in 1921 with his first pointed-gear design. Utzon's boats are considered to be the fast, elegant ones. He had a reputation for being keen to experiment.

Georg Berg was a trained shipbuilder who developed his skills from sailing practice. His boats are characterised by slender, rather narrow sterns with small cockpits and plenty of deck space.

Hansen was the youngest of the three, but his designs are regarded as harmonious-looking, very seaworthy boats. Only his designs crossed the finish line in the legendary Sjælland Rundt storm race in 1935. Full sterns are one of his trademarks. A sister ship to "Neptun" was built according to Hansen's plans in 1937. This was to rot in the USA. However, the bestseller of the pointed stern class was the approximately 7.5 metre long 30.

Technical data "Neptune" spider gate

- Boat class: 55 m2 pointed gate

- Design: M. S.J. Hansen, 1937

- Year of construction: 1964-1971

- Torso length: 9,98 m

- Width: 2,98 m

- Depth: 1,85 m

- Weight: 7,0 t

- Mainsail: 41,22 m²

- Foresail: 16,22 m²

More on the topic:

Andreas Fritsch

Editor Travel