Al Stewart wrote his famous song "The Year of the Cat" for the year 1975 - according to Vietnamese astrology, it was the year of the cat. Thomas Stinnesbeck was coming of age at the time, having just returned from a year abroad in California. And he passes his A-levels with a grade of 1.0; "the teachers kind of liked me," he says. In this respect, it was a significant phase for him. "We both like cats, and the music in the title also appeals to us," say owners Thomas Stinnesbeck and Uta Schüller, explaining the choice of name for their ambitious self-build, which plays with the word "cat" as well as its deeper meaning.

Read more about other self-builds:

Two 120 hp engines push the Rhinelander's mighty vessel into the open water off Corfu. In order to be able to sail, Stinnesbeck now also starts the 4 kilowatt diesel generator. "The electric motor for the furling hydraulics draws 2.2 kilowatts, the 230-volt converter should actually supply 2.5 kilowatts of continuous power from the batteries, but the engine still only runs agonisingly slowly," he says, explaining the enormous forces and currents - and the need for the diesel generator. A sprint to the port bow to clear the sheets, a glance into the aft chamber and 100 metres have already been covered. An ordinary swimming pool helps to emphasise the enormous dimensions of this project. Only a narrow strip of water would remain free around the "Year of the Cat".

Plans for "Year of the Cat" as a Christmas present

"I had actually wanted to build a monohull by the designer Reinke in the 1980s," he explains the current abundance, but his plans cost a five-figure sum. He wanted to save money and the drawings for that 20-metre cat were already available from designer Bruce Roberts for 800 marks. "That was already a lot for me back then, I gave it to myself for Christmas at the end of the 1980s."

However, it was to take over 20 years until the keel was laid. "I only ever rolled out the foil plots at Christmas time. You have to understand them first," says the self-builder. "After having the plans for 15 years, I then built the cat for the first time as a fretwork on a scale of 1:20." Whether it would ever be built in its original size remained uncertain at first.

Thomas Stinnesbeck remained very busy professionally. He founded a software company and subsequently launched their hearing aids internationally for Siemens. And he opened more hearing aid branches on his own. He personally manufactures their fittings. To this end, he is building a combination of 200 square metres of flat and office space and 600 square metres of hall in his home town of Willroth, halfway between Cologne and Frankfurt, mainly - how could it be otherwise - by himself. "Building is not that expensive," he comments on the dimensions. If you do it yourself: "I can only recommend aerated concrete, brick on brick. I had the steel scaffolding erected, but I wove the reinforcement for the strip foundations myself again."

The hall is primarily being built for carpentry and storage of the counters, but Thomas Stinnesbeck is secretly working on two other projects. After some consideration, he devotes himself to the smaller of the two: the 20-metre cat.

Blue water almanac and rocket technology

Originally, the hall was also intended to deepen his other passion. He holds three patents in Germany, the USA and Japan for injection systems for hybrid rocket engines. "Together with a few other fanatics, I built the largest of its kind in Germany, I think to this day." The technology is currently being used in the experimental aircraft Spaceship One. But at the time, he was barely able to convince the space authorities of what he considered to be a much safer fuel. In the on-board library, alongside the area guides and the Blue Water Almanac, there is specialised literature on rocket technology such as "Space Propulsion Analysis and Design". "At some point, I asked myself which of my slightly crazy dreams I could realistically realise. And the boat won out."

The sailing dream stems from dinghy rides on the IJsselmeer and charter trips, totalling around 5000 nautical miles. At least he can transfer the experience of epoxy processing from laminating the test propellants for the boatbuilding workshop. Stinnesbeck first digitises the plans and familiarises himself with the Turbocad design program. The plan envisages epoxy-coated plywood. A CNC milling machine fed from his data was to speed up the creation of frames and planks, "but it cost around 100,000 euros". He will therefore be building his own CNC panel milling machine with control electronics from 2010. 2011 is another year of the cat - anything is possible.

To continue saving costs, he uses birch multiplex panels instead of boatbuilding plywood. "The wood is completely encapsulated with glass and epoxy later anyway, and multiplex is also extremely impact-resistant," he replies to the sceptics.

Extensive preparatory work pays off

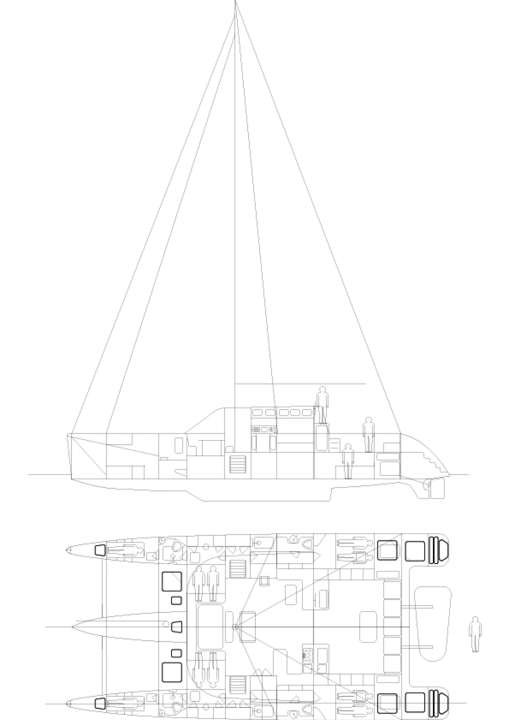

At the time, some of his friends believed that the catamaran would never be finished. Understandably so, because in 2012 he was only building the components for another 1:10 scale model, now two metres long, on his self-built milling table to test its buoyancy. He also abandoned the original idea of offering berth charters and reduced the number of berths to ten and the number of compartments to six. In any case, the somewhat vague plans for the design of the cockpit, bridge deck and cabin superstructure give him maximum freedom.

Thomas Stinnesbeck uses the gap in the plan and raises the coaming by a few hand spans to give the floats a room height of 2.20 metres. The same applies to the bridge deck, a loft with a navigation corner. It also gives the cabin superstructure its distinctive rounded shape. He achieves this with the "radius chine" construction method developed by South African designer Dudley Dix, originally intended for round underwater hulls of plywood hulls.

The success of the extensive preparatory work pays off, "the CNC router is like a second man, it runs in the background and you can do something else for so long". Because processing the multiplex wood proves to be a tough nut to crack; it takes around an hour to saw the parts out of a 12-millimetre board in five depth settings. "In the meantime, I experimented with a 150-watt laser and movable mirrors" - until his partner Uta Schüller vetoed the idea, saying it was too dangerous if someone were to reach into the beam. In any case, the laser cuts poplar plywood "like butter", according to the aerospace specialist, but with multiplex boards with their phenolic resin bonding, there is a problem. The explanation of the boat-building rocket designer: "No wonder, the stuff was already on the Apollo capsules. It decomposes under heat until pure carbon remains, but this only melts at 3500 degrees."

Furnishings for "Year of the Cat" from the furniture store

Stinnesbeck's construction process is similar to the "Lisoletta method": "In many self-build projects, the shell is completed first and then painstakingly removed, but in my case it was the other way round." All the notches, every light switch and every socket have already been milled before the respective component goes into place. All the frames are also cabin walls, berth sections or cupboard walls; there are no fixtures in the true sense of the word. Uta Schüller shows what is behind the large louvre doors directly opposite the companionways in the two hulls. The household freezer on the port side holds several hundred litres, and the solar cells on the aft equipment rack are sufficient for its operation, as they are for the large refrigerator next to the fitted kitchen. This is located in front of the walk-in pantry. The washing machine and dishwasher are also comparable to normal household appliances - and two of the four bathrooms are even larger than many on land.

While the sails, mast, winches and technology come from maritime suppliers, the furnishings include a number of items from furniture stores. Dozens of white shoe cabinets have been installed as storage compartments for odds and ends, while the kitchen equipment with its self-closing drawers fits exactly into the CNC-milled corps. In the bathroom, the mirror frame, shelves and the mounting plate for the massage shower are made of inexpensive bamboo, which fits perfectly here.

A visit on board reveals even more. The yacht is not built for the comparatively narrow area between Corfu and the mainland; cruising or any manoeuvres at all are not her strong point, nor are light winds. The eight to nine knots of thermals allow a speed of up to 3.5 knots. "We don't actually take the sails out below ten to twelve knots of wind," comments Stinnesbeck. Then engine power is the order of the day. The tanks on both sides of the wooden keel stringers hold just under 1000 litres of diesel, and the water tanks, which are usually filled from the watermaker, hold just as much.

The spaceship devours €450,000

In light winds, the discreetly suctioning transoms are also noticeable, the cat brakes a little with the heels. For better maintenance, Stinnesbeck installed the two engines two bulkheads further aft instead of under the aft berths. He also chose stronger and therefore heavier models than the designer had intended.

During the next visit to the shipyard, either the fore-and-aft trim is to be improved, "or we'll paint the water pass aft higher". In general, there are a few repairs to be made, and the two tell us what has already broken in the first year of the circumnavigation of Europe: hatch opener, plotter, water pumps, exhaust manifold, log, plumb bob, rudder angle indicator and oil pressure gauge. The electric foghorn had already failed twice, two rudder arms broke and three electric toilet pumps were wrecked. When the plastic clip on the ball head of the engine control unit popped off in a lock of all places, the life's work, which suddenly found itself travelling backwards, could have been badly damaged.

When Stinnesbeck sold his company to the market leader during the construction period in 2016, he could have ordered a boat of this size in one go. Instead, he is delighted that he no longer has to save on rigging, sails and fittings. "When you've lived from hand to mouth for years, it gets into your bones. Even today, I sometimes have fears of loss and bad dreams because of it. I hate being wasteful, although that has eased a little. My children are now very big spenders." Nevertheless, two employed helpers speed up the work on the private shipyard at the time. Stinnesbeck estimates the total costs at around 450,000 euros by the time his spaceship is hauled down the Rhine, the mast is set and the sails are hoisted.

Stress test for family and friends

They now have the technology, the sail area and the many details on board under control, and the steady course westwards around the world seems just one last visit to the children away. The self-builder is now preoccupied with completely different things. He used to go jogging a lot. He is glad to have the electric winches installed, "but I'm thinking about installing an electric treadmill, I've already looked at a few models," he says, adding that he can well imagine trotting to windward in the terrace-sized cockpit. His partner is less enthusiastic about the idea - there isn't that much space to store things. She prefers to swim eight laps around the cat every day, each of which is around 70 metres longer than a lane in the Olympic swimming pool.

"16 metres long would have been enough," Thomas Stinnesbeck is certain today. And he has a whole series of tips that he would have liked to have known back then. "Before you start something like this, you should really think about whether it would be better to join an owners' association to reduce costs and sail rather than work. What's more, most people forget that the big sums come at the end of a yacht project: That's when the winches, the sails and the plotter are due." In addition, the idea of starting with a new boat after building it yourself is wrong, "that's wrong, the stuff has been lying around for years". And you should realise what such a project means for family and friendships, "if you're always crawling around in a hull like that. I'm sure more than one marriage has fallen apart over this."

Technical data "Year of the Cat"

- Length: 19,95 m

- Width: 9,70 m

- Depth: 1,40 m

- Weight: 22,0 t

- Mainsail: 85 m²

- Genoa: 85 m²

- Code Zero: 150 m²

- Tanks: 2000 litres of diesel, 2000 litres of water

Two hulls, three models, six years

With 300 sheets of multiplex wood and a tonne of epoxy, the two hulls are built in the self-build hall. Like the birth of twins, the two parts, which are still separate, are transported outside on the low loader and to an open building site in Neuwied on the Rhine. Thomas Stinnesbeck completes them there with the bridge deck. A short time later, cranes lift the cat into the Rhine after six years of construction. Stinnesbeck milled three models for the planning, one exclusively for planning the installation. He marks every single opening for cables and hoses on it with adhesive dots.

The article was first published in 2019 and has been revised for this online version.