A fine fountain of spray rises from the bow of the Leeschwimmer, signalling that we have just passed the 14-knot mark. A quick glance over our shoulder to windward - yes, the dark spot on the surface of the water is getting closer, we're about to get more pressure. Time to drop five degrees. Seconds later, things really take off.

The gust is there, the Code Zero is literally tearing the tri forwards. 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, finally we are racing across the Little Belt at more than 21 knots. The amazing thing is that apart from continuously dropping to follow the increasingly sharp wind, there is nothing to do during this orgy of acceleration. The buoyancy reserves of the swimmers cope with the pressure without any problems, so that not even the heeling increases noticeably. Only the height and intensity of the spray fountain downwind and the increasingly direct steering feel indicate the speed.

The Dragonfly 36 test video

Development and construction of the Dragonfly 36

Jens Quorning and his team spent around 2.5 years designing and working on the new Dragonfly 36 before the first hull of the new model was presented in the middle of last year. The 36 celebrated its official premiere at boot in Düsseldorf, where it proved to be a crowd-puller. YACHT already presented the boat at that time. Barely six months later, the fifth boat is under construction and there are 28 orders - enough to keep the family business at the exit of the Kolding Fjord busy for over a year. "Of the smaller models, we have built up to 60 boats a year, but in the 40s and 36s, so many man-hours are being put in that our capacity has dropped to around 24 units per year," explains shipyard manager Jens Quorning.

The meticulous work of the Danes can be clearly seen on the three boats under construction at various stages during the boatyard tour. The hull shells are made by hand as a sandwich with a Divinycell core and are laminated by X-Yachts in Poland. Quorning produces the highly stressed beams and bulkheads on site using a vacuum infusion process. The finished components are then annealed.

Also interesting: Dragonfly 28

Handling and features of the Dragonfly 36

The outstanding feature of the 36 is the composite folding hinges integrated into the structure. Previously, these were made of stainless steel and bolted to the hull and the beams. "Now we laminate them together with the GRP bulkheads to create a homogeneous unit. The finished plastic part is then cut to size using a CNC milling machine. This eliminates the time-consuming adjustment of the hinges, and the Tri is also lower maintenance and lighter without the metal parts," says Quorning, explaining the advantages of the new design.

On the water, the composite hinges work just as unobtrusively as the metal versions of the previous models. Once the folded Tri has been manoeuvred out of the harbour, all you have to do is open one halyard stopper on each side. As the floats are pushed a little deeper into the water when folded, they automatically swing out when unfolded. The standard electric winch is only required for the last section and for the final push-through of the backstays. The entire folding process can be conveniently controlled from the helm and takes barely a minute, about the same time it takes for the gigantic 73 square metre squarehead mainsail to climb the mast. It is set with a 2:1 halyard, with the powerful electric winch once again providing good service.

Performance profile and speed

The gennaker also comes out of the bag, or rather out of the float, so that you can leave the shore cover quickly. The four large stowage spaces in the floats not only hold the dinghy and folding wheels, but are also ideal for storing bulky sail bags. With a wind of around twelve knots, the boat moves swiftly but calmly towards the Little Belt at a speed of eight to twelve knots.

The Tri is very neutral on the rudder. The steering has a relatively high reduction ratio of one-third of a turn from hard to hard. This means that comparatively long steering travel is required at low speeds and under engine power. As soon as the forest-fringed banks recede, the wind picks up a little, causing the log to climb further. 14 to 16 knots are shown on the clock on the beam reach.

As the speed increases, the grip of the thin carbon fibre rudder also increases and the necessary steering movements become smaller. Beyond 15 knots, the Dragonfly begins to hang on the wheel like a go-kart.

To realise the full potential of the tripod, we switch to the Code Zero. Like the rest of the wardrobe, it comes from Elvström and is driven on the test boat with an electric furler from Facnor integrated into the bow nose. The system works extremely quickly, unfurling or furling the 67 square metre sail takes barely ten seconds.

Including the Epex sails, the shipyard charges just under 26,000 euros. The cheapest hand-operated version is available for around 11,600 euros. Regardless of the cost, the code really gives the Tri a boost. Under gennaker, the boat's speed corresponds roughly to the wind speed. With the Code, this limit falls. As the wind picks up at the same time, the Dragonfly constantly sails at around 19 knots, with every gust immediately being converted into additional speed.

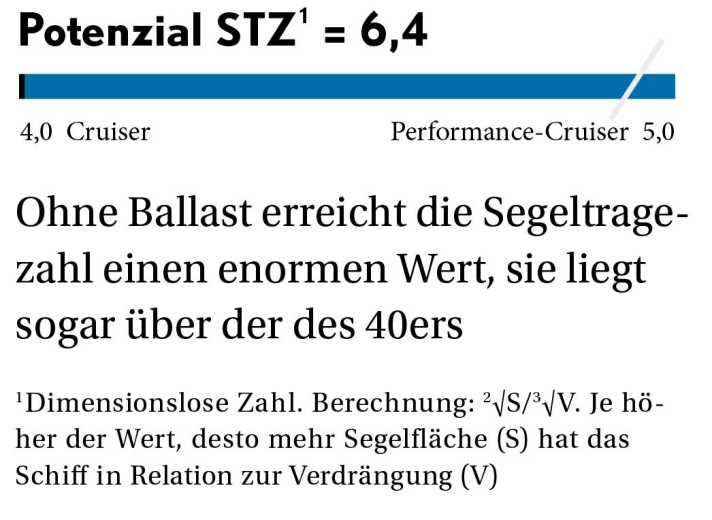

At the end of our test, the top speed was 21.6 knots in around 19 knots of wind. This means that the 36 even outperforms the top value of the 40-foot top model, which we tested in comparable conditions. One reason for this could be the advanced floats. Unlike the 40-footer, they are asymmetrical and have a flat underwater hull. This design is common in current regatta tris and ensures better water drainage and less drag. "We wanted to be able to laminate two floats at the same time and built double moulds. Asymmetric hulls were therefore logical," says Quorning.

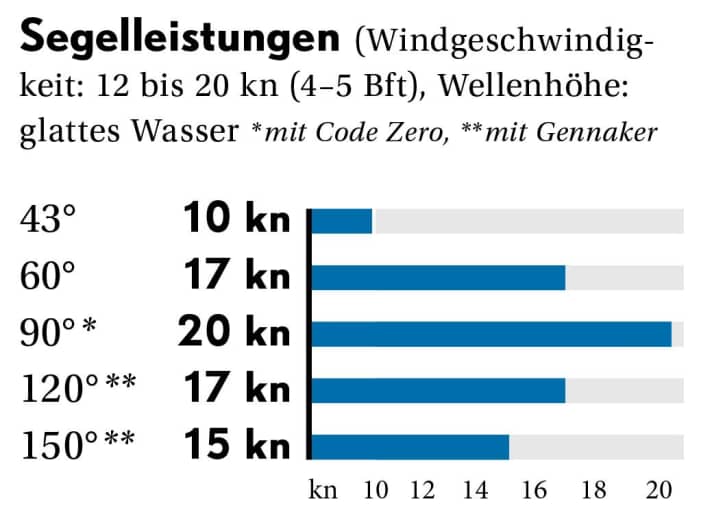

It is one thing to be fast under sail or with half the wind, but the way to windward is usually much more arduous. The Dragonfly also benefits from its good hydro and aerodynamic design on the cross. With a true wind angle of 43 degrees, the Tri sails at around ten knots, which results in a speed to windward of 7.5 to 8 knots. Values that owners of similarly sized monohulls can only dream of. Striking on the cross: the Tri runs like on rails on the wind edge and hardly requires any corrections. However, we do miss the sprayhood, which is not fitted for visual reasons, as the airstream and true wind add up to a stiff and very cool breeze.

Interior fittings and comfort of the Dragonfly 36

As only the slender centre hull is inhabited, it is cramped below deck on trimarans. The 36 is no exception here. However, as with the 40, Quorning has opted for a special bulkhead shape for the main hull. While the underwater hull is slim and sharply cut, the width above the waterline increases significantly, creating space.

The layout corresponds to the monohull standard with an aft cabin. The cabin is located under the cockpit, but offers headroom in the entrance area and a pleasant amount of headroom above the berth. This comes at the cost of the low mattress position. The bed lies on the floorboards.

The obligatory escape hatch provides a view of the sea, while additional light is provided by optional hull and cockpit windows. Storage space, on the other hand, is tight. There is no wardrobe here. The only wardrobe is located opposite the toilet in the foredeck and is small. On the other hand, the saloon and the cabins are equipped with all the more cupboards. In the saloon, the wide strip of windows and a large deck hatch provide daylight. The opening hull windows installed in the test boat are also available on request. The fixed side windows in the foredeck are standard. The integration of the centreboard box is a good solution; it replaces the table base and is therefore hardly disruptive.

Overall, the interior fittings impress with their excellent workmanship. The woodwork with moulded edgings is just as flawless as the silk matt lacquer finish. The gaps are perfect and the elm veneer is beautifully matched. This is one of the reasons for the enormous surcharge for the real wood interior. Quorning uses an ash imitation on the bulkheads as standard. This eliminates the need for time-consuming veneer selection.

Market placement and price

The Dragonfly 36 is practically unrivalled with its combination of elegant, cruising interior and enormous sailing performance. Older trimarans such as a Corsair 37 cannot keep up in any discipline and even the 40-foot top model from the Danes is likely to find it difficult to keep up with the agile Dragonfly. The price of the boat is also unrivalled. Due to the manufacturing-style production and the significantly higher construction costs, any comparison with monohulls is misleading. Nominally, the Dragonfly costs around 2.5 times as much as a monohull of the same length. This would have more space, but nowhere near the same speed potential. A similarly fast monohull, on the other hand, would easily have to be twice as big and would therefore be in a completely different sphere in terms of purchase and maintenance costs.

Base price ex shipyard:

- Touring 627.130 €

- Performance 659.260 €

Further prices:

- Price ready to sail 650.522 €

- Comfort price 689.638 €

Status 2025, how the prices shown are defined, read here!

Standard equipment included:

Engine, sheets, railing, navigation lights, battery, compass, main, genoa, cushions, galley/cooker, bilge pump, toilet, fire extinguisher, holding tank with suction, mooring lines. At extra cost: E-refrigerator compartment €2,350, sailcloth €1,276, anchor with line and winch €7,336, fenders €154, antifouling €7,325, clear sailing handover €4,951

Guarantee/against osmosis 2/5 years

Surcharge for comfort equipment:

- Line adjus. Hole points 1.369 €

- Traveller with line guide unf.

- Electric windlass incl.

- Tube kicker incl.

- Backstay tensioner unf.

- Jumping cleats 541 €

- Sprayhood 4.189 €

- Smartdeck in the cockpit 4.189 €

- VHF radio 2.309 €

- Log and echo sounder 5.819 €

- Wind measuring system incl. logger

- Autopilot 10.383 €

- Charger incl.

- Shore connection with RCD incl.

- 230-volt socket outlet (one) incl.

- 12-volt socket in the sat nav incl.

- Heating 5.694 €

- Pressurised water system incl.

- Hot water boiler 2.219 €

- Shower WC room 1.541 €

- Cockpit shower 863 €

Included in the price:

Carbon fibre rig, ball-bearing mast slides, four electric winches, 800 watt inverter.

Other variants:

Expansion

An ash replica is used for the standard version. The elm real wood veneer on the test boat costs €23,878 extra.

Motorisation

A 40 hp engine can also be selected instead of the 30 hp Yanmar. However, it hardly makes the Tri any faster and is only recommended in combination with the 230-volt alternator from Dynawatt.

Elektro-Furler

On the test boat, the Code Zero could be furled with an E-Furler from Facnor. The system works very well, but costs an additional €25,912 with the matching sail.

Electric cooker

The shipyard offers an optional electric cooker with oven. However, this also requires the optional lithium batteries. Everything together costs €14,917 extra.

Shipyard & distribution

Quorning Boats Aps, Skærbækvej 101, 7000 Fredericia/Denmark ; Tel.: +45/75 56 26 26; www.dragonfly.dk

Technical data Dragonfly 36

- Designer: Olsen Design/Quorning Boats

- CE design category A

- Hull length 11,55 m

- Total length, folded 13,43 m

- Waterline length 10,90 m

- Width 3,70/8,12 m

- Draught 0,67-2,00 m

- Mast height above WL 16,50/18,50 m

- Theor. torso speed 8.0 kn

- Weight 4,5 t

- Ballast/proportion 0,0 t/0 %

- Mainsail 61/73 m²

- Furling genoa (108 %) 32,5/37 m²

- Machine (Yanmar) 21.3 kW/30 hp

- Fuel tank 70 l

- Fresh water tanks 200 l

- Holding tank 80 l

- Batteries 3 x 82 Ah + 1 x 70 Ah

YACHT review Dragonfly 36

Hardly any other boat offers the enormous average speeds paired with relaxed sailing. The typically limited living space in a trimar is well utilised, so there are hardly any compromises to be made compared to the 40-footer. The price is enormous, but can be justified by the manufacturing quality on offer.

Design and concept

Convincing folding system

On manoeuvrable design

Can fall dry

Hinged sword instead of a plug-in sword

Sailing performance and trim

Speed potential very easy to access

One-handed operation

Very agile and comfortable

Living and finishing quality

Very good space utilisation

Moulded edge banding

Ash only available as a replica

Equipment and technology

Very high-quality fittings

E-winches as standard

Very clean installations

(+) Carbon rig as standard

Hauke Schmidt

Test & Technology editor