Banka "Libelle": Through the islands of the Philippines in a traditional outrigger canoe for under €1,000

Egmont Friedl

· 19.10.2025

- Outrigger boats in the Philippines are called banka

- Sails made from household or tarpaulin fabrics

- And half a coconut shell with copper nails

- Ritual sacrifice of a chicken for the baptism of a banka

- Learning from local fishermen

- Travelling on your own with a small boat

- The Banka's engine is reduced to the essentials

- Technical data of the Banka "Libelle"

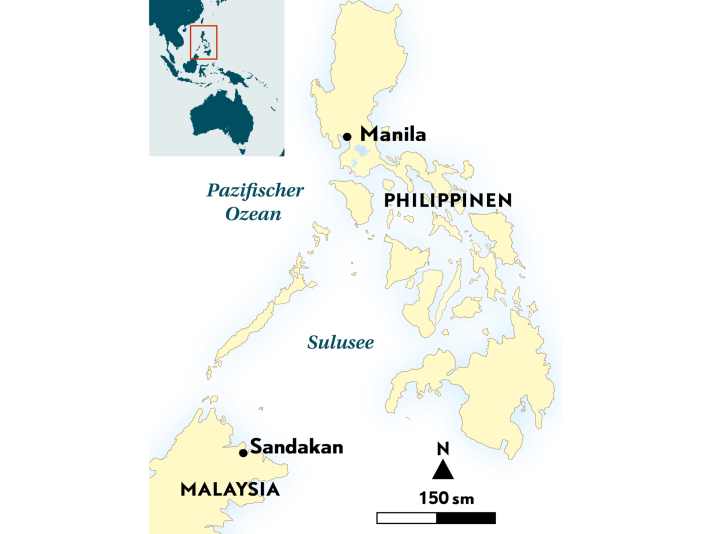

The Philippines consist of 7,645 islands, only 880 of which are inhabited. I'm spending a month in the summer with my friend Josie on a tiny, jungle-covered island with two sandy beaches and eight inhabitants.

We climb the hills with a bolo, a Filipino machete. Josie is a child of the jungle, she knows all the plants, dangers and medicinal herbs. We eat guavas, wild mangoes, tamarinds and descend on the windward side of the island through almost impenetrable jungle to a wild cliff. Here the monsoon blows incessantly, the view is out to sea, and the sailor in me quickly realises: to travel this part of the island, you need a boat, preferably your own! The idea was born.

Other special boats:

Anyone who commissions a custom design usually belongs to an exclusive circle of well-heeled yacht or superyacht sailors - but it doesn't have to be that way! And what sailor doesn't dream of having a boat built to their own specifications? When Josie and I made this decision and some time later found a boat builder on the island of Panay, we recorded the most rudimentary details of the build as a "contract" on a page of my logbook. Length: approx. ten metres, engine: diesel, construction time: two weeks (! - excluding rainy days), boat type: banka for sailing/paraw. Boat builder Ariel, 40 years old, makes a good impression, and as a European boat builder, what should I tell him about how to build a boat here? Here, it's not much more than a few bamboo huts on the beach.

Outrigger boats in the Philippines are called banka

A couple of wooden stools are quickly set up in front of one of these huts and Ariel, Josie and I sign our contract under the gaze of everyone from quietly observing elders to wide-eyed, astonished children. Start of construction: tomorrow morning! The price for our finished ten-metre-long banka with motor and mast is the equivalent of just under 1,000 euros.

Just imagine, we'll have our own boat, not even that small, with the outriggers probably over five metres wide, we can sail whenever and wherever we want, and we'll have an engine too. Let's install a few solar panels and a battery, then we can even put a small fridge below deck. The Philippines have never seen a boat like this before!

The outrigger boats are available up to a length of 30 metres, and even with this impressive size, the bamboo outriggers are only fixed with lines.

The outrigger boats in the Philippines are called banka. They can range from 2 to 3 metres in length to impressive sizes of 30 metres. A banka of our size is fitted with a petrol or diesel engine to which the propeller shaft, which has a correspondingly small propeller at its end, is attached directly without a gearbox. Before you start the engine with a line around the flywheel, which requires not only strength but also skill, you have to point the bow towards open water, as the boat immediately starts to speed off as soon as the engine fires. It is not possible to disengage the clutch!

The hull is narrow and extremely sleek and has outriggers on both sides, called katig, each made from a long bamboo cane. The outriggers are connected with crossbars bent over an open fire, called tarik, which are also made of bamboo. The entire construction of the outriggers is held together with strong lashings of thick fishing line and connected to the centre hull. This is done even on the largest banka.

Sails made from household or tarpaulin fabrics

So my first custom boat is a trimaran, and it's my first multihull in my sailing career with 14 boats and yachts of my own so far, which I've owned for travelling and cruising halfway around the world. Many sailors switch from monohull to multihull as they get older, mainly because of the comfort. However, there is no question of comfort with our boat.

In the past, of course, the banka sailed under sail and were called Paraw, Vinta, Bigiw or Balangay, depending on the type and location. Today, there are only paraws for tourist excursions on the island of Boracay and an annual paraw regatta in Iloilo. These paraws (pronounced "parau") are impressive, motorless boats. The high central hull is around eleven metres long and only an incredible 40 centimetres narrow. It cuts through the water like a blade, simultaneously acting as a centreboard and reacting very sensitively to the longitudinal trim of the boat. The crossbeams are enormous and are made of hardwood on the Paraws. They extend about 6.5 metres to either side and each carries a huge bamboo cane as a float. At over twelve metres, the width of a paraw is greater than its length! This is considered an extreme platform for multihull boats.

The sails of a Paraw consist of a main on a steep gaff and a strongly rising boom in the shape of a crab claw sail and a small jib. The sails have no real cut and are made from household or tarpaulin fabrics. It is all the more impressive to watch the crews of a paraw. They are two or three guys who sail every day for years from the main island of Panay to the small tourist island of Boracay, earn their money there and return in the evening. The paraws are extremely fast on a half-wind course, but would be too big and too heavy for Josie and me, especially to pull the boat onto the beach.

The boat is extremely simply built and has almost no equipment. Battery, solar cells and a fridge are the only comforts we can afford.

We are staying in a bamboo hut a few minutes' walk along the beach and have the indescribable pleasure of walking to Ariel and the others at the building site every day and watching our boat being built.

And half a coconut shell with copper nails

On the first day, the keel is built up from a single piece of carved lawaan, also known as Philippine mahogany. The stem and sternpost are connected at their ends with a hook shackle and wedge lock. They are made of molave, a very durable native tropical wood. On the second day, three main frames are erected and aligned on a line.

The beam walkways are made of shafted mouldings, also from Lawaan. They work very skilfully here, and I admire the skill of Ariel and his brother under the local conditions. They have to make do with the simplest of hand tools, which would be unthinkable here. No work table, nothing to clamp onto, just a handsaw, two chisels, a hammer, a clamp, a metre rule, a pencil and half a coconut shell with copper nails. But there are also one or two putties, because nowadays even here all the joints are additionally glued with epoxy. On the third day, all the frames are already fitted into the keel with mortise-and-tenon joints and embedded in the beam travellers.

These are now stretched upwards at the ends with ropes so that we can admire the pronounced bounce of our boat for the first time. On the fourth day it rains tropically, which is why we can't work and everything gets completely wet. While a European boat builder would have a complete crisis over this, nobody here cares about the soaked wood. On the fifth day, the first five-millimetre-thick plywood sheets are nailed to the sides of the hull.

Ritual sacrifice of a chicken for the baptism of a banka

When we return to Panay after a holiday back home, our boat is as good as finished. We install solar panels, a battery and a small fridge, and buy a welded stock anchor, which is the only type used here. Above all, however, we rig the square sail I brought with halyard and bream to our bamboo mast. A Filipino artist skilfully paints the name of our proud boat on the sides of the hull: "Dragonfly". Lightweight, floating, nimble and colourful are the attributes we want our boat to have.

Before the launch, however, there is still the Philippine way of christening a boat. Modern man has to go through this. A white chicken is ritually sacrificed to christen a boat and its blood is used to protect the most important parts of the boat from harm. I agree to this on the condition that the chicken is also eaten afterwards.

After the archaic deed with mumbled incantations, blood sticks to the engine, keel and stem. Then we push the boat into the sea in strong winds. "Libelle" pitches and flies over high waves. Ariel is not yet completely satisfied. Back on the beach, he bends the quickly removed propeller shaft between two rocks to remove an imbalance and pushes the propeller blades into a slightly lower pitch. The crazy thing is that after these adjustments, which would make any mechanic either throw up his hands or have a fit of laughter, there has actually been an improvement. Then Ariel prepares our baptismal sacrifice in a sauce with onions and lots of lemongrass. It tastes delicious.

Learning from local fishermen

We sit down in the lee of the beach, looking out over the stormy sea, our minds a mixture of joyful anticipation and caution. The Philippines are not an easy spot! The next day, we pack our equipment on board: a tent, a mat made from banana leaves, some provisions, cooking utensils and my wingfoil equipment. We push "Libelle" into the water and pull her into deeper water using the anchor we had deployed earlier.

Over the offshore coral reef, I head out into the waves at the deepest point. I turn off downwind and along the coast. After the cape of Caticlan we are in calmer water. We come to a beautiful, wide beach where we want to stay. Again, we first have to find a passage over the reef, then drop the anchor over the stern, stop the engine and jump ashore with the bow line, where we can tie up to a palm tree.

We are happy to have mastered our first short trip and found a good spot. With long lines and a strong buoy, we pull "Libelle" all the way onto the beach. In the evening, we lie in the tent and look out to sea and across to the west coast of Boracay. You might think that after more than 40 years of sailing experience, thousands of miles single-handed and in small boats, three Atlantic crossings and a few extreme journeys, you'd know all the tricks of the trade. But that's not the case! I have to learn a lot of new things, and that's what's important, beautiful and challenging. You can learn a lot from the fishermen here, and the more you try to do the same, the more you realise how much toughness and skill is demanded of them in their little bankas.

Travelling on your own with a small boat

Over the next few days, we motored out into the wind again and again, then turned "Libelle" downwind, stopped the engine and tested our square sail. This is also something completely different: you can't turn into the wind or take the pressure off the sail. The wind pushes into the sail and the sleek boat sets off immediately. However, the bamboo outriggers do not have so much buoyancy that they can really prevent capsizing. They dip and sink quickly, and caution is advised in the event of a sudden gust. That's why I inserted a small piece of wood into the halyard as a toggle so that I can throw it off at lightning speed with a pull on the pull line and toggle, whereupon the upper boom rushes down to just above deck.

However, one marvellous advantage of a square sail is that there are no patent jibes. You can sail flat in front of the sheet without worrying and without yawing to one side. If I hoist the yards, i.e. close-hauled the sheets, we can tack up to a half-wind course. But our boat is also very unusual for the Philippines. Paraws never have an engine and bankas never have sails. We are a mixture of the two. This also means that we have a rudder in the style of the paraws, but smaller because the propeller shaft still protrudes aft under the rudder. Our "Libelle" reacts to rudder movements with the inertia of an oil tanker, which takes some getting used to.

It is hot day and night, mosquitoes are a nuisance. The night in the tent is tropical. But the next morning you are happy, sitting on the beach with a cup of coffee. "Dragonfly" floats in front of us, and the feeling says: ready for the next crossing!

We sail to the large island of Tablas and spend wonderful days on the beaches again. In the Philippines, nobody travels by small boat. There are ferries and there is island hopping in the tourist areas, but travelling on your own in a small boat is unheard of here. The fishermen only ever go out to sea in their own area. And another thing: a woman on board, who also steers the boat, that's twice as rare here!

The Banka's engine is reduced to the essentials

On the island of Sicogon, we pack our tent and equipment into waterproof bags in the morning, carry them on board in the waist-high, 30-degree water and climb onto our "Libelle" via the bamboo outriggers. We use ropes to turn the boat round so that we are pointing the bow towards the anchor. I kneel on deck, push open the hatch to the engine, turn it a little over dead centre by hand, adjust the fishing line to the throttle, put the line around the flywheel, straighten up, bend my knees a little, look at Josie, who is ready at the bow to pick up the anchor. Then I pull the line upwards with my whole body. You have to do everything right, otherwise the engine will turn in the wrong direction, because it can do that too!

The engine, which can be started by hand, is reduced to the essentials. There is no gearbox, exhaust, shaft bearing or filter. But it always works.

There is no diesel filter, no oil filter, no alternator, no electrics, the engine is air-cooled and has no exhaust, just the manifold. Furthermore, there is no gearbox, no stuffing box and no shaft bearing, no shaft seal either, just a long piece of pipe in which the shaft runs. And off it rattles. Josie picks up the anchor. The stick anchor works amazingly well, always finds a hold, in rocks as well as in sand. I quickly ease off the throttle and we leave the marvellous sandy beach. And so we move from island to island, a dream!

Technical data of the Banka "Libelle"

- Torso length: 9,80 m

- Wide centre fuselage: 0,98 m

- Width with outriggers: 5,60 m

- Length of the outriggers: 9,00 m

- Depth: 0,30 m

- Weight: 0,5 t

- Mainsail: 15 m²

- Sail carrying capacity: 4,9

- Machine: 18 PS