A text by Ricarda Wilhelm

Finally, after 26 days and nights of seemingly endless sea, we've made it: the silhouette of Hiva Oa appears ahead. Our longest ocean passage to date is behind us. The last land we had seen was the Las Perlas Islands off the coast of western Panama. Now I'm sitting in the pulpit and savouring this moving moment. And wondering what awaits us. How much of the original Polynesian culture is still left? What discoveries will we make on the Marquesas Islands, what kind of people will we meet?

We clear in at the Atuona gendarmerie. We receive a warm welcome. As Europeans, we are allowed to stay for three years, but our boat is only allowed to stay for two. "Enjoy the Marquesas. They are beautiful. If there's anything, I'll be happy to help you," the friendly policeman tells us. The second aisle leads to the supermarket. The shelves are stocked with local products as well as various goods from France and New Zealand. Everything is relatively expensive. We were prepared for this, as the islands are more remote than few other places in the world. However, the fruit and vegetable displays are meagre. Over the next few days, we learnt how to stock up on fruit on board on the islands.

Strolling in Atuona

Atuona invites you to take a stroll. We discover a Gauguin exhibition. The painter placed the women on "Te Fenua Enata" the "islands of men", as the Marquesas were called before they were discovered by Europeans. Stone sculptures adorn the town's fairground. They bear witness to the indigenous culture of Polynesia. The oversized heads on much too small bodies emphasise the eyes and mouths. The figures are Tikis. We will encounter them all over the Marquesas in the following weeks.

A Christian church stands nearby. Polyphonic singing can be heard from the neighbouring building. I peer curiously through the open window. Men and women are sitting at tables, some playing guitar and ukulele. The unfamiliar Marquesan lute sounds soft and harmonious. Some of the women wear a frangipani flower over their ear - just like in Gauguin's paintings.

There are several yachts in the anchorage whose crews have been here for a while. We are supplied with fruit. "You have to ask the locals. They give away and sell fruit. You can also swap it for lines or fishing hooks," advises a German sailing couple who have been in the Marquesas for three months. "Polynesia is not only beautiful, we can also spend the hurricane season here without any risk," they say.

To explore Hiva Oa, you can hire a car and visit some of the archaeological sites. Or sail around the island. Our plan: first via Tahuata in a clockwise direction to the north of the island and then from the easternmost cape with a layline to Fatu Hiva. From there we will then head to the northern islands of Ua Huka, Nuku Hiva and Ua Pou. This means that all the inhabited islands are on our route.

Anchorage off the neighbouring island of Tahuata

We sail through the Canal du Bordelais with a cross aft wind to our first anchorage, Baie Hanamoenoa on the nearby neighbouring island of Tahuata. Our "Lady" rushes through the water, attracting the attention of a group of dolphins. They come with long leaps to surf in our bow wave. The sandy bottom in the anchorage bay provides very good holding. The backdrop is magnificent: black rocks on which the swell breaks with white foam, framing a golden beach with coconut palms.

The turquoise-coloured water is perfect for snorkelling. Fish of all colours nibble on the algae-covered rocks. Suddenly, a huge manta ray floats beneath us. It gallantly turns somersaults and presents itself in all its splendour. We watch mesmerised and forget the time.

We then cross the channel back to Hiva Oa and head for its north-west coast. This is much rockier and drier than the south side. Individual bushes cover the stony ground, which sometimes shimmers silver-grey, sometimes reddish. At Cape Kiukiu we are greeted by an unpleasant choppy sea and a headwind. Dolphins appear again, at least 20 of them this time. They accompany us all the way to Baie Hanamenu. Here, too, the panorama is spectacular: rock faces populated by seabirds on both sides frame a narrow green valley. In the centre are the remains of an abandoned village. Only one fruit farmer still lives here. He cultivates an extensive garden in which mangoes, citrus fruits, coconuts and papayas thrive. The grapefruit on the trees are so big that their branches bend down to the ground.

The farmer greets us warmly and offers us mangoes and lemons. When I ask how much it costs, he refuses. "I want to swap, do you have any rum?" he asks. I shake my head sadly. "It's all empty, it was too far to come here," I come up with an excuse so as not to embarrass the friendly man. He asks if we have any cartridges. When I give him a perplexed look, he pulls out a pack of ammunition. We learn that the locals use it to shoot wild goats that have spread across the islands.

The north coast of Hiva Oa

With a long cruise we sail eastwards to Baie Hanaiapa. On the way, we marvel at the rugged north coast of Hiva Oa. From the mountain ridge that runs from east to west across the island, narrow, rocky ridges drop down to the shore. Only the upper slopes are covered in green fluff. The clouds on the south side are obviously raining down.

Hanaiapa is a lively and very well-kept village. On a Saturday, it is used by many islanders as a summer retreat. Picnic tables and benches are set up under shady treetops. Freshly washed pick-ups gleam in the sun. Marquesans enjoy their weekend with coolers, surfboards and swimwear. We watch as an outrigger boat drops off passengers. Freshly painted, it shines like a lemon butterfly on the blue sea. There is no jetty, everyone has to jump into the deep water off the steep stone beach. Only their heads peek out. Only small children and their luggage remain in the boat, which is now pushed onto the beach by the adults. The boat is pushed up the steep slope over palm trunks with combined forces. It's hard work, but everyone is in a good mood.

Against wind and current to the Eastern Cape

The next morning we set off for the Eastern Cape with more cross-ships against the wind and current. Damn, the weather forecast had predicted a completely different wind direction and strength! Exasperated, we finally start the engine. At the cape, the Pacific crashes violently against the rocks. Impressive, and with only ten knots of wind. You can imagine what goes on here in a storm. As we round the cape, we can drop off and set sail again. Fatu Hiva soon comes into view.

As we pass the west of the island, the sun sets and bathes the eroded rocky coastline in warm light. The stone folds vertically like a woman's skirt. Narrow minarets stand in the vertical wall. I discover new sculptures from every perspective.

Then we turn into the Bay of Virgins - and can't get our mouths shut: Mother Nature has created a huge basalt gateway here with the remains of a crater wall. Hanavave lies at the bottom of the large island-forming volcanic crater, framed by narrow, bare walls that rise up to 360 metres into the sky. Other smaller volcanic mountains form a varied landscape. Rainwater runs down the rock faces and feeds a river.

Of scarce goods and works of art in the Marquesas

Local residents make ample use of these almost paradisiacal conditions. The valley is overflowing with all kinds of fruit trees. As soon as we set foot in the village, we are offered grapefruit, mangoes and breadfruit. There are also plenty of chickens, pigs and goats, and even a few cows. Self-sufficiency seems to work here. A small shop also sells more exotic products such as rice, sugar, shampoo and chocolate. Only vegetables are in short supply. The supply ships "Aranui 5" and "Taporo IX" come regularly from Papeete, 1,000 nautical miles away. But nobody knows in advance exactly what and how much they will bring.

In Hanavave, we pass the property of Sissi and Simon. In their garden, among all the greenery, lie roughly carved blocks of stone. Simon is a carpenter and sculptor, while his wife knows the art of carving. "I learnt it from my father," she says. Suddenly we find ourselves in a workshop with a number of tiki figures made of wood and stone in various sizes and stages of production.

Simon then proudly shows us his carpentry work. Among other things, a table with a chequerboard pattern, surrounded by a wide frame and decorated with carved tikis: It is a true work of art! Simon uses black ebony and reddish-brown rosewood. Two perfectly crafted chairs, whose backrests are decorated with Marquesan patterns, stand ready next to it.

Simon explains the Marquesan cross to me. We find this pattern in many of his works. "Inside you see the islands, around them the sea. The edge represents Mother Earth in the universe. That's why the symbol is round." The figures are divided into male and female. All those with a long plait are women. "This one here with the high hat is even a queen," the craftsman tells me, pride resonating in his voice.

Inside the island crater

The next bay is reached early in the morning the following day. Omoa, the island's main town, is also located inside the large island crater. The journey takes us past several smaller volcanoes. Cliffs, rock sculptures and narrow green valleys form a picturesque landscape. Every homestead in Omoa has its own stone tiki on fence posts or at the entrance. They are said to protect family and home, bring luck and prosperity. A sculptor shows us his work. He works with wood and stone, but also uses cattle bones or horns and long swordfish daggers.

The tall, strong man skilfully combines the materials. I ask him about his tattoos. He proudly shows me the two intertwined rings on his chest: "This one symbolises me and the other my wife. We are connected." Then his finger moves to his neck. There, the patterns stretch across his collarbones like necklaces. "These are my children, and this pattern here on my arm symbolises my father," he says with great seriousness in his eyes and voice. Polynesians honour their ancestors. Similar to the gods, they are involved in current decisions and rituals.

All good things come in threes

We leave the south of the archipelago and make three stops on Tahuata before travelling to the northern Marquesas. This time we are accompanied by a group of pilot whales on the way. Our destination is Hapatoni. The village lies in a wide green bay. The surf hits the rocky beach in a steady rhythm and discharges in high fountains. Fortunately, there is a small harbour behind a natural headland where ferries, private boats, water taxis and the gendarmerie moor. With a stern anchor, our dinghy is neatly moored in front of the concrete pier. It's worth going ashore.

A long promenade of cobbled earth and black lava stones leads through the village. Huge old almond trees lean over the water. The sea has already washed away some of their roots and will probably soon take the giants completely. Ancient foundations and wide terraces of black basalt structure the hillside. The village church is also built from the round rocks. Next door is the cemetery.

Next, we head for the island's main town. We make leisurely progress downwind of the rocks. The coast of Tahuata is dotted with caves, one after the other. Vaitahu lies in front of a green rock face and is full of flowering shrubs. Unfortunately, the museum is closed, a supermarket offers the essentials and at "Chez Jimmi" we are finally served one of the famous Marquesan goat dishes. They are said to be the best in the world - which we can confirm. It's the first time in my life that I've eaten such tender goat meat.

On a walk through the village, we meet Teii, who invites us onto his property. "I have pumpkin, grapefruit and mangoes for you." We follow the thin, wrinkled man. His property is large, the house is hidden under the crowns of old mango trees. Teii's mother sits on a bench and greets us cheerfully. Delphine is 74 years old and proudly points to her vanilla plants.

A green net over our heads protects the sensitive plants from too much sun. Teii shows us the flowers, holds them carefully, almost lovingly, and opens the tiny capsule with a toothpick-like twig to extract the pollen. The white, sticky dust is barely visible, but is immediately carried to another flower to fertilise it.

"Why aren't the bees doing this?" I ask in amazement. "They take care of the fruit trees, they can't do this," Teii explains. He points to the many green pods on the vines. The work is worthwhile, he says, he can sell them well. I, on the other hand, realise for the first time why vanilla is so expensive.

Barbecue on the beach

We have to motor to Hanamoenoa, three nautical miles away, the next day. We stay in this northernmost bay of Tahuata for a few days. There are two fire pits on the beach. Other sailors have already left barbecue grills, iron pots and pans there. We look through the palm trees past the campfire to the anchor field. We grill fish and sausages, accompanied by salads, fruit, wine and beer. Places like this are perfect for chatting with other sailors, exchanging experiences or simply enjoying the moment together.

The next destination, Ua Huka, is further away, 65 nautical miles. It takes us just under twelve hours to reach our fourth island in the archipelago. The bay of Vaipaee is narrow and long. It is reminiscent of a mini fjord. We pass through the narrow entrance as if through a canal, with walls up to 70 metres high on both sides. The swell reflects several times, creating a choppy cross sea that makes the water surface bubble. Metre-high fountains hiss through the holes and cracks in the shore stones.

Like Fatu Hiva, Ua Huka consists of a curved half crater wall. The southern side was eroded by the sea. A high red mountain rises up inside the former caldera. The long main town lies in a green valley. We have to walk a few kilometres to cross it. The supermarkets, town hall and post office are located directly on the main road. It leads up the slope. Idyllic properties nestle deeper into the valley between the crowns of fruit trees and palm trees. We discover an unusually large number of horses roaming free here.

Crater walls tell the story of the Marquesas

As beautiful as Ua Huka is, the anchoring conditions are rather modest. So we soon set course for Nuku Hiva, 33 nautical miles away. Taiohae Bay is large but open. There is swell. Fortunately, there is a sheltered quay where we can moor the dinghy between the fishing boats. Fruit and even vegetables are sold directly in the harbour. There is a tourist office next door where you can hire a car to explore the island. There is also a post office and three well-stocked supermarkets. Taiohae could be described as a real small town. Life is buzzing, the main street is frequented by many vehicles and quite a few of the inhabitants speak English.

A trip to the north coast is worthwhile due to the spectacular rock formations. Castles millions of years old, formed from molten lava, are enthroned with several towers on the ridge of the mountain range. They are the remains of eroded crater walls. Black and mighty, they tell of the history of these islands and provide unique photo opportunities. The road to the north leads through an extensive archaeological site. Archaeologists classify Kamuhei as a sacred ceremonial site. Large parts of the area have been uncovered. We marvel at the remains and also the size of this former settlement.

Huge strangler figs catch our eye. The largest was a burial site. It is said that the skulls of former victims of ceremonial cannibalism, the most sacred part of the human body, were hung in the aerial roots. The mighty tree towers impressively some 80 metres into the air. Its aerial roots become thin trunks, fusing together and forming a unique impenetrable wooden network around 20 metres in diameter.

Next stop: Daniels Bay

We reach Daniels Bay with a crosswind. It lies so deep in the bay that we end up surrounded by rocks and almost feel like we are on a lake. At the end of the valley on the left is the 350 metre high Ahuii waterfall. The hike there leads past abandoned terraces where palm trees, banana plants, mango trees and weeds are now rampant.

Apparently, Hakaui was once a thriving settlement with many inhabitants. A kilometre-long paved path the width of an oxcart leads to a platform that was once used for ceremonies and festivals.

We reach the neighbouring island of Ua Pou to the south after a five-hour crossing. The main town of Hakahau is located on the north-east coast. Here, too, the cliffs are spectacular. The clouds linger at the highest point of the old volcanic crater. At 1,232 metres, Mont Oave is the highest peak in the entire archipelago.

Hakahau has a breakwater and therefore a fairly quiet harbour. Unfortunately, the museum is closed, as are the restaurants and a bakery. We caught a Sunday afternoon. Locals are barbecuing on the beach, watching their children playing in the sand or swimming with them at the concrete ramp. The long beach lies almost unused in the sun. Only a few tourists are in the water to survive the afternoon heat.

Dance as a tradition in the Marquesas

A few days later, the "Aranui 5" docks at the quay in the morning and unloads goods and tourists. Now we can see how many inhabitants the island has. Everyone is on their feet. People gather in the community centre for a traditional Marquesan dance. Women adorned with wreaths of flowers stand behind long tables selling souvenirs. Their colourful dresses compete with necklaces of red beans, mother-of-pearl shell jewellery and shiny wood carvings. Thick green leaves are laid out on a long table, on which women spread a kind of fruit salad.

The islanders don't just come to earn money from the tourists. For them, too, it is a festive day when people dress up, meet, socialise and enjoy life. Everyone is waiting for the highlight of the event. They are the dancers: tattooed, half-naked men with loincloths, bones around their necks and feathers on their heads. They represent indigenous warriors and impressively demonstrate their strength and willingness to fight with their posture, movements, body jewellery, facial expressions and roars. The bright voices of the women, on the other hand, are reminiscent of the Asian origins of this people; they clearly enhance the battle cries of the men.

After the performance, I ask one of the muscular performers: "Do you only dance for the tourists or also for yourself?" His answer: "I dance for the boss up there, for the sun and moon, for Macron, for the tourists - and for myself. I love it!"

Interesting facts about the district

Te Fenua Enata

The archipelago was once referred to as the "Earth of Men" by its indigenous inhabitants. It has been inhabited for around 2,000 years; the first people probably came to Hiva Oa from the west. It was a Spanish explorer who renamed the islands the Marquesas in 1595. Today they belong to French Polynesia. Of the 14 islands of volcanic origin, six are inhabited. The highest peak at 1,232 metres is Mont Oave on Ua Pou. The islands have almost no sandy beaches and no fringing reefs or lagoons like those found elsewhere in the South Seas. They are very rugged with deep valleys. To windward of the mountains, tropical rainforest covers the slopes, while on the leeward side they are mostly bare. The anchorages are often located in sunken volcanic craters. The climate is tropical with lots of rain and average air temperatures of 28 degrees Celsius. It cools down considerably at night.

Tiki, ancestor of mankind

The stone or wooden figures with oversized heads and eyes represent gods and spirits that bring strength, protection and healing. They are part of Polynesia's millennia-old culture, which has been revitalised and in some cases recreated since the end of the 20th century. In the Marquesas, there are museums on Tahuata (Vaitahu), Nuku Hiva (Hatiheu) and Ua Huka (Vaipaee).

Marquesan for beginners

- Mave mai - Welcome

- Kaoha - Hello

- Vaieinui - Thank you

- Kaikai Meitai - Bon Appetit

- A Pae - Goodbye

On a foreign keel through the archipelago

Instead of sailing there yourself, you can hire on another yacht. Many long-distance travellers need crew for the Pacific passage - or money. Some sailors join up in Panama or on the Galapagos Islands. Suitable berth offers can be found on the Internet. On site, you can join the "Aranui 5". This is not only a freighter and ferry, but also a cruise ship. It serves the Tuamotus and Marquesas from Tahiti. The ship calls at almost every island and takes paying guests on board, for whom shore excursions are also organised. There is hardly a better opportunity to see the otherwise closed museums as well as local dance performances and handicrafts. The Marquesas can be reached by plane via Papeete/Tahiti. Hiva Oa, Nuku Hiva and Ua Pou have airports.

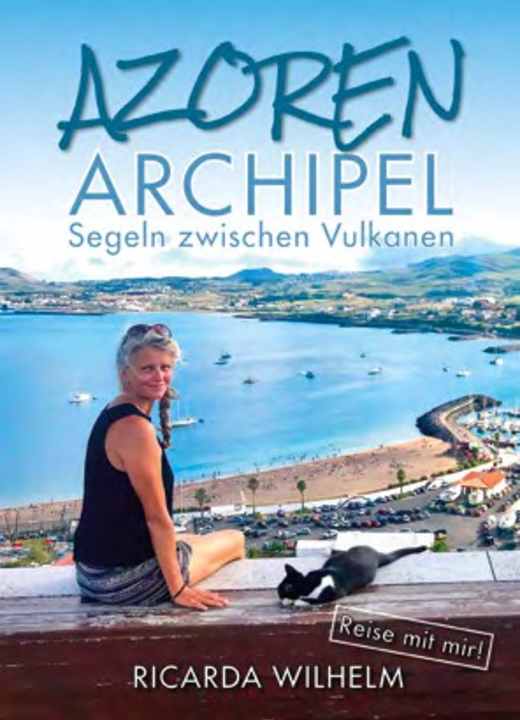

The author

Ricarda Wilhelm has lived with her husband on the Amel 54 "Lady Charlyette" since 2018. She publishes her travel stories digitally and in paperback. In YACHT, she recently reported on the volcanic eruption on La Palma and the most beautiful bays in Martinique. You can follow her everyday life on board at ricardawilhelm.wixsite.com/travel-with-me and on Instagram ( @travellemitricarda )