Regatta: The technical innovations of the Vendée Globe boats

A simple comparison shows just how rapidly technology is developing in the Imoca class: while only seven of the 29 starters at the last Vendée Globe four years ago were sailing on foils - a quarter - this time the figure is already more than half: 17 out of 33 boats are competing with hydrofoils. Foiling has become the norm in the class. Only teams that can finance a retrofit are competitive. The cost: at least 600,000 euros.

New foils - the decisive factor

The arms race hardly stops anywhere. There are decisive innovations in almost all areas. Nowhere, however, is the lead through technology as great as in wings. Compared to Alex Thomson's previous "Hugo Boss", which competed in 2016 with by far the largest and most aggressive airfoils, these have now become significantly longer for almost all top teams. They generate a lot more lift and therefore a more upright momentum than before. When fully extended, they lift the 60-foot yachts so high out of the water at high speed that only the appendages plus a small, perhaps three or four square metre section of the stern floats. In other words, the Imocas now fly more than they sail.

The differences between the profile shapes are still significant, which is mainly due to the different philosophies of the designers. Quentin Lucet, designer at VPLP in Vannes, who specialises in the development of the appendages for the office, explains: "There is a difference between the foils that we design compared to those of Guillaume Verdier, for example. Ours are designed so that they are lower in the water and push the boats quite high out of the water early on, as with 'Charal' or Boris Herrmann's 'Seaexplorer'. We think this is important for two reasons. Firstly, the profiles are less susceptible to ventilation deeper in the water because they draw less air. Secondly, a foil is better protected against collisions with flotsam on the surface of the water."

On the Verdier boats, on the other hand, the wings are significantly narrower and at the same time more expansive. In fact, in the course of the further development of some teams, it has been observed that they have retrofitted the foils with up to six small longitudinal bars to prevent the intake of air (ventilation).

Many top teams have developed at least two foil versions for their current campaign, and some, like co-favourite Jérémie Beyou from "Charal", have even developed a third. This was partly necessary because the profiles have made another technological leap. For the first time in this Vendée, they are also adjustable by five degrees along the longitudinal axis. This means that they can be adjusted in the angle at which they press into the water - similar to a landing flap on an aeroplane. This was still prohibited in 2016.

The effects of development are enormous. "Depending on what stage of evolution a boat is at, a new foil can easily improve performance by 10 to 20 per cent in the right conditions," says Lucet.

Alex Thomson's "Hugo Boss" and "Arkéa Paprec" by Sébastien Simon and the Sam Manuard design "L'Occitane en Provence" have developed significantly different foils to the competition. The first two have huge, almost circular airfoils, which they can retract completely into the hull as they do not touch above deck - an advantage in the light wind zones near the equator. This is because the wings usually only work from around ten knots of wind upwards; below that, they slow the boat down. It will be interesting to see whether this advantage will actually have a significant effect in the Doldrums, for example - or whether particularly light boats such as "Linked Out" with a large spinnaker will be just as fast.

The real aim must be to maintain high speeds for as long as possible. For Alex Thomson, it is therefore clearly a tactical means to have the fastest boat in the field: "After the start, it will be a drag race to the Southern Ocean. If we manage to take even one or two knots off the competition in ideal conditions, that's a 25 to 50-mile lead the next day," says the Briton.

After the start of the Transat Jacques Vabre last autumn, he already indicated that this was exactly what he was aiming for: Only in the back of the midfield, he went around the first mark on the wind, and when the wind and angle of incidence were right, he ploughed into the lead at express speed, at times making even the eventual winner "Apivia" look pretty old. This is probably why VPLP founder Vincent Lauriot-Prévost considers him to be the top favourite.

The quantum leaps in foil development entail a whole host of changes to the boat, as Boris Herrmann learnt when retrofitting his "Seaexplorer". The structure of the boat had to be reinforced because the long foils transfer much more force into the hull. The same applies to parts of the stern, as the loads are brutally increased by the thundering swell.

Paolo Manganelli, chief engineer at Gurrit, development partner of most of the top teams for the development of the laminates, recently said that they are laminated in highly stressed areas from almost twice as many layers of carbon fibre, but only half as thick, 150 grams per square metre instead of 300 grams. The consequences are complex: more laminating processes, more complicated venting and tempering of the components in autoclaves.

This also applies to the foils themselves: Up to 300 layers are placed on top of each other, laminated and compacted. The component has to be tempered every three layers.

Customised sails for less drag

The fact that the boats are now flying earlier and earlier and are therefore becoming faster and faster is also changing the sails. Many teams are switching to flatter laminated profiles and dispensing with spinnakers, instead only taking gennakers and code sails on board. Thomas Ruyant goes one step further with his "Linked Out". Similar to the current America's Cuppers, he dispenses with a large part of the upper headsail and the sail head is much lower. The idea behind this is that the narrow part of the sail at the top creates more drag than desirable propulsion at the high speeds of the boats.

Autopilots - better than any helmsman

A completely different quantum leap has taken place in the development of the autopilots. Compared to the last Vendée, these have reached a level that makes the boats significantly faster - because they can now process even more data much more quickly. They are fed no less than 25 times per second (!) with data from the anemometer, compass, gyro sensors for position and waves, acceleration and load sensors from foils and rigging. They are connected to the central computer via fibre optic cables - a high-tech network in the middle of the most inhospitable seas imaginable.

Software specialists in the teams adapt the algorithms so that the autopilot executes the optimum rudder commands within a wide range of parameters - faster and more complex than the best skipper could ever do, and without any signs of fatigue. In "Beast Mode", the most radical level, this leads to downright brutal course corrections that can be frightening - but keep the boat foiling for as long as possible.

Predictive camera systems

Boris Herrmann has gone even further and coupled the Oscar camera system with the pilot at the masthead. If the computer unit detects a potential collision based on the video image and infrared images, it automatically initiates an evasive manoeuvre - and can thus help to avoid serious damage to the ship or foil. Two thirds of all Imocas will be racing with Oscar for the first time at this Vendée Globe.

Aerodynamically perfected hulls, protected cockpits

With the higher speeds, two further points have come into focus: to reduce the wind resistance of the boat and to improve the safety of the skipper in heavy weather.

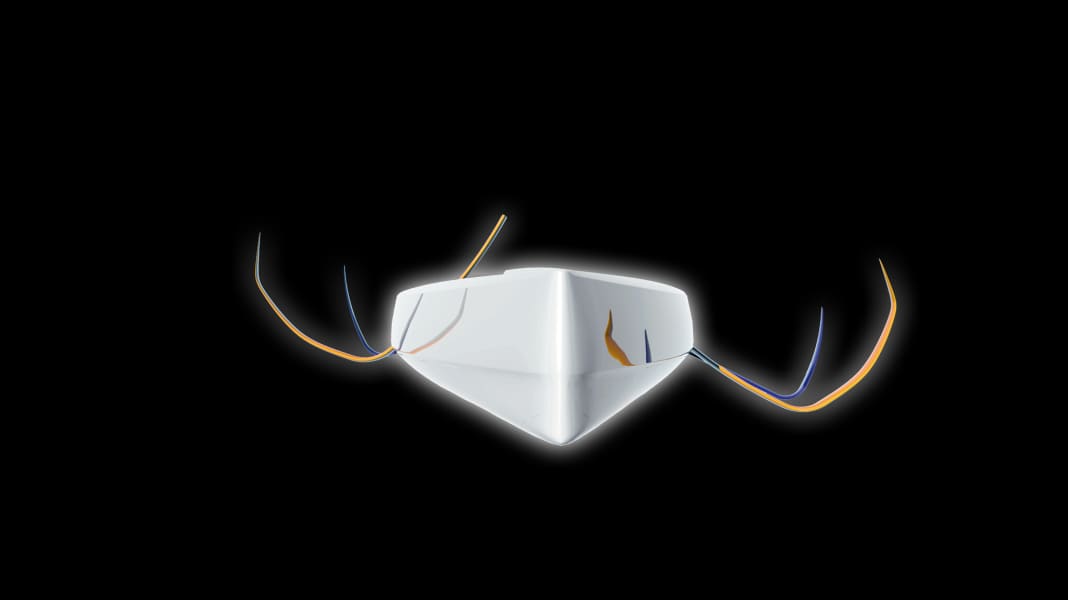

The most extreme way to achieve this was taken by Alex Thomson. His new "Hugo Boss" has a super-flat deck. The cockpit is located directly underneath, behind the mast, i.e. as low as possible in the boat, and it is completely enclosed. This means that nothing slows down the propulsion, not even overflowing water, and the skipper remains protected in rough weather. There, in the centre of the boat, are not only his bunk, his cooker and the navigation instruments, but also all the trim equipment and even the tiller. Camera systems allow the Briton to keep an eye on the sail trim from his "submarine" and keep an eye ahead. The cockpit can only be exited via a tiny hatch at the stern and an emergency hatch in the roof. Thomson was the only one to pursue such a radical approach. But the trend towards ever more sheltered, deep cockpits, often almost closed aft, is clear.

Standardised masts and keels

One pleasing aspect of the last two generations of Open 60s is that they have become more reliable. To achieve this and to reduce costs, the class switched to one-design rigs and deck spreaders as well as keels and hydraulics before the last race.

As a result, the number of technical damages in these areas decreased significantly; failures were mostly due to collisions with flotsam or whales. This was confirmed by the skippers at a recent conference on the future of the class.

The future of the Imocas in The Ocean Race and at the next Vendée was also discussed at the meeting. An important topic was whether T-foils would be permitted on the oars. This would allow the boats to lift the entire hull out of the water.

"I think this is the next logical step," Quentin Lucet from VPLP told YACHT. The Frenchman had already analysed corresponding designs and is also a designer on the technical committee. There is no question that it is feasible.

However, due to the uncertain financial future of many teams as a result of the coronavirus crisis, it was decided to postpone this next step. After all, it would again entail a lot of development work - and would take the existing boats even further away from the next generation in terms of performance.

In the last edition, the best non-foiler finished almost a week later than the winner. The gap will probably be even greater this time.