Philipp Hympendahl: Non-stop solo trip around Great Britain and Ireland with a hurricane on his back

Philipp Hympendahl

· 07.11.2025

We set off late in the afternoon on 16 July. I leave the harbour bay of Poole on the southern English coast with my nine-metre-long "African Queen". Coming from IJmuiden in the Netherlands, I first had to seek unscheduled shelter from a storm and then have a loose upper shroud repaired by a professional rigger. Anyway, I start my project from here: I want to try to sail around the whole of Great Britain and Ireland on my own and without stopping in the harbour.

Only recently, Boris Herrmann's "Malizia" completed the same route as part of the Course des Caps regatta - in six days and six hours. I won't be that fast. Nevertheless, it is an incentive to emulate the professionals.

More on the topic:

As soon as I'm out at sea, the twilight is replaced by darkness. At around 11 p.m., I'm about to start taking short naps when I spot two yachts coming towards me. I'm on the port bow and have the right of way, but I stay awake. That's a good thing, because one of the boats is heading towards me undaunted. So I change course to avoid a collision. I vent my anger on the VHF radio. I get an apology, but that doesn't help to calm my pulse.

During the night, the wind drops a little, visibility deteriorates and fog settles over the water. The weather forecast for the Celtic Sea is very mixed, with a bit of everything. I therefore decide in favour of prudent seamanship and some sleep in the bed of the Helford River near Falmouth. There I drop anchor near the estuary at a depth of about four metres.

A few other boats are already moored here. The densely wooded bank is less than 50 metres away and is dotted with small stretches of beach. On the other side of the river is a picturesque panorama: green hills with pastures are interspersed with large trees and a few cottages. The play of light from the sun and clouds the next morning gives the place a magical glow. I spend several days anchored here.

Then a weather window opens up for the Celtic Sea and I can continue my journey in the early morning of 22 July. Land's End, the famous landmark at the end of the English Channel, lies off at midday. As a young man, I once stood up there and looked down on the sailors. Now I pass the rocks on my own boat, in sunshine, light winds and with a proud spirit.

In the afternoon, I swap the British host country flag for the Irish flag. The wind direction forces me to make a wide arc to the north during the night. Later I can set course for Fastnet Rock with a downwind course and reefed sails. On the way there, the wind dies down more and more and I reach the lighthouse off the south-west coast of Ireland at a snail's pace. This seems almost strange, as we sailors tend to associate the turning point of the legendary Fastnet Race with rough conditions.

Most sailors are drawn eastwards from here to Cork. The town on the south coast of Ireland is a mecca for sailors, with the oldest yacht club in the world and one of the largest natural harbours. But I head north-west and approach a rugged stretch of coastline that is defenceless against the North Atlantic. The swell rolling in here builds up over thousands of nautical miles. As I sit under my sprayhood and gaze lost in thought into the distance, my gaze lingers on an unusual shape: A pointed, long fin protruding from the water some distance away. Shortly afterwards, water shoots into the air as if from an atomiser. The dorsal fin moves powerfully through the sea and others join in: orcas! I watch the animals through binoculars and am glad to know they are at a distance.

The weather becomes more Irish

A fur-lined fleece jumper that I once bought in Hamburg for a trip around Denmark in winter is in constant use. It becomes like a second skin to me. I pass the fjord-like bays and finger-shaped headlands of the Irish south-west in 15 knots of westerly wind. The long swell gently lifts the boat up and then lowers it again. Nature shows its muscles, but doesn't flex them. Not yet.

My alarm goes off after 20 minutes of sleep. I wake up immediately, leave my dream and look at the position. Then I climb onto the large step of my engine box and lean far out under the sprayhood to look in all directions into the cloud-covered darkness. No ship in the vicinity, no lights to be seen. So I shimmy back into my bunk, restart the timer, tuck myself in and leave this world for another 20 minutes.

Stronger winds are on the way, I have to make sure I get away from here. As I try to anchor on the coast, I suddenly find myself in chaotic seas. The "Queen" is being buffeted on all sides by metres of towering water and thrown onto her sides. I quickly decide to turn away and head seaward again until I'm back in calmer water. I look for a new anchorage and find another one 25 nautical miles ahead in the natural harbour of Ballyglass.

Queen's stage to St Kilda

Hours later, I finally pass the small lighthouse at the entrance to the bay. The shallow surroundings don't ward off the incoming gusts, but the anchorage near the beach is good and there is no swell. I'm glad to have found a sheltered spot. From a distance, I recognise a village on the edge of which there are a few houses, some derelict and empty. On the other side of the bay, a hilly panorama stretches out under a contrasting cloud cover. The sun breaks through a few times and lights up the meadows in lush green. Welcome to Ireland!

The next day is the royal stage: Far to the north, away from the Hebrides, lies the small uninhabited island of St Kilda. This is my next waypoint, over 200 nautical miles across the open North Atlantic. I drop anchor at midday, and in the afternoon I am treated to a visual spectacle, which I alone am allowed to witness and in whose presence my love of the sea is once again confirmed: A low-hanging band of clouds is illuminated from behind by the last rays of the setting sun. This conjures up an orange-coloured light in the sky, which is reflected on the waves, while my "African Queen" glides alone into the near darkness.

At midday on 29 July, St. Kilda lies abeam. Unfortunately, the island is hidden under a deep cloud cover. Only a flat strip of coastline is visible. The colourless view can't dampen my joy. From here, I continue on to the Orkneys. But then I receive bad news from my German marine weather expert Sebastian Wache on my Iridium app: "Gale force winds from 5 August, real danger! As of today: direct hit."

Hurricane on the way

It is midday on 31 July when I leave the northernmost point of the journey behind me. North Ronaldsay is an inhabited island a few kilometres long with a few wind turbines, a few houses and a lighthouse. As soon as I've passed it, I can drop off and head south.

Knowing that the Orkneys are in my wake is a great relief. But the weather forecast presents me with a difficult decision: a front is blocking the way south, and because of the approaching hurricane I can't wait until it has passed. This means that I can expect winds of up to 30 knots and correspondingly high waves at the headland of Peterhead tomorrow morning.

In the morning, I change course so that I can get through the strong wind with some distance to the coast. The current runs against me while the wind pushes from behind and the sea builds up. When a wave pushes the boat, the hawser of the previously deployed drift anchor tightens and the "Queen" stays on course. The sun appears again and again between scattered clouds and provides some comfort. It finally calms down in the afternoon.

Imagination vs. reality

Over the next few days, I come across an area with few anchorages during an approaching gale. Due to the initially light winds, I only reach the mouth of the Humber River in the dark. Many lights are shining and twinkling, the distances are much greater than I had expected. I carefully carry the individual parts of the anchor gear to the foredeck and connect them. Then I cross the main fairway and head upstream towards the anchorage as the tide comes in. The wind from ahead is now picking up strongly. The current is pushing from astern. A steep wave builds up. Suddenly, the plastic box of my anchor chain moves over the foredeck and threatens to fall into the water. I manage to get everything back into the cockpit just in time. That was close! Losing the chain or anchor would mean the end of this challenge.

I had chosen the anchorage based on a handbook and detailed charts. However, the reality the next morning was not what I had imagined. Misjudged proportions and a rusty fort from the Second World War in the first light of day reveal an unexpected reality. The protective bank is barely recognisable in the distance, and the other side of the river is also better explored with binoculars than with the naked eye.

Before the first front approaches around midday, I quickly let the second anchor slide down to the bottom as a weight. That's all I can do. And then the wind comes. In the afternoon, I film how the bow rises and falls in the waves as if I were at sea. It rattles the mast and whistles in the rigging, I can't switch off. The wind only dies down towards the evening, at least overnight.

Territory demands more than an Atlantic crossing

The hurricane has been given a name: "Floris". In the Hebrides, where I've just been, wind speeds of up to 200 kilometres per hour are measured. In the morning, when it's still calm, I make a decision: I start the engine, and shortly afterwards I'm standing at the pulpit pulling on the rope, chain and anchors until I lift the main anchor on deck with my last ounce of strength.

Even as I head downstream towards the estuary under foresail, the wind picks up. The jib is almost completely furled, but the "Queen" is still sailing parallel to the coast at four to five knots, heading towards a wind farm. The pressure in the sail increases again and again, but not in gusts for a brief moment, but at long intervals and with unexpected force. The atmosphere only calms down in the afternoon. I set an easterly course to round the large headland in the south-east of England.

In the dark, the tide pushes the boat parallel to the coast at speeds of up to nine knots. But the area has both sides of the coin: the wind has shifted, the tide has shifted, and so I cross along the coast at bad turning angles and almost come out at the same landmarks.

My exhausted body and tired mind can do nothing to counteract the moral low that is building up inside me. As a single-handed sailor, this area challenges me more than my Atlantic crossing. There are always new challenges that I have to overcome in an overtired state. Starting with the weather, which is constantly changing, currents, shallows, fishing nets, lack of sleep, exhaustion and loneliness. I wanted to test and practise making the right decisions from this state on this trip. Because that's my job as a single-handed sailor if I ever want to sail solo non-stop around the world.

After 26 days: done!

With the setting sun, I set off on the final leg through the English Channel. After a tough cross at Dover, I make good progress. It's the 11th of August. Friends of mine are standing near the Needles and take a photo of our arrival. The "Queen" is a small white triangle, lost in the vastness of the sea.

After 26 days, I'm back in Poole. "Yes, I've made it!" I shout in the direction of my GoPro camera. At the entrance to Poole Yacht Club, I pull the string of a flare to celebrate my arrival with the greatest symbolism. The harbour master comes running up, startled, and asks if anything has happened. Later, I'm sitting in the restaurant, relieved and happy. Pint in hand, I look at the masts: "This is the only harbour you've seen," I confirm to myself.

On the way back to the Netherlands two days later, two different German boats and sailors meet: my 45-year-old "African Queen" encounters the flagship of German ocean sailing, the "Malizia Seaexplorer", which is on its way to Southampton as part of the Ocean Race Europe. Unfortunately, it is dark when the black silhouette with flashing top light passes in front of the sparkling coast near Brighton in the light wind as if on rails.

But my "Queen" also shows herself proudly, under full sail, illuminated in the headlamp light of her tired skipper. Two worlds meet here for a brief moment, only to sail off into the night in opposite directions.

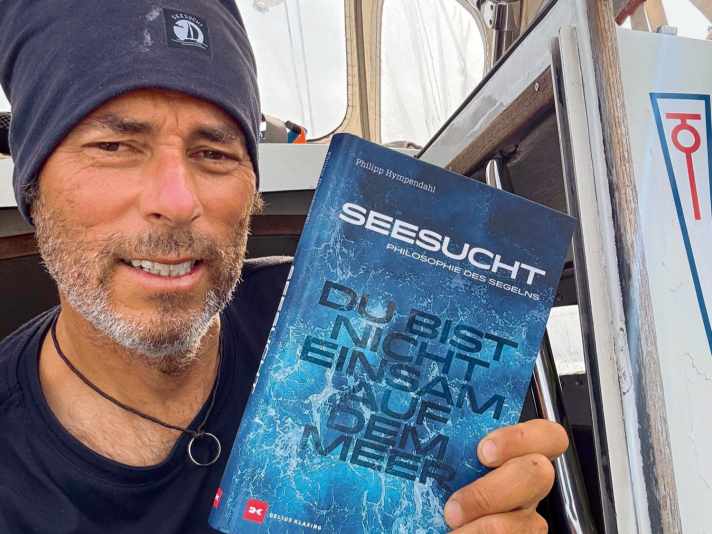

Reading tip: "Seesucht" by Philipp Hympendahl

In his book, Hympendahl shares the experiences of his Atlantic voyage on a 9-metre boat to the Caribbean and back. 26,90 Euro, shop.delius-klasing.de